We are living in the era of the web.

The applications you instinctively check on your smartphone upon waking are

web-based; the programs you face at work are also web-based. From casual

chatting to information searches, there is virtually no online activity that

operates outside of the web. Even Tim Berners-Lee, who founded the World Wide

Web, once mentioned that he did not anticipate the web to wield such an

influence when he first created it. What started as a small spider’s web has

now grown into a massive structure. But in fact, what we actually perceive is

not the web itself, but the images produced by the web's giant network.

Let’s take a closer look at your immediate environment as you read

this. You likely encountered this critique as text displayed on a screen; you

visited a site to read the article and clicked a link with the title.

Throughout this entire process, what you perceived can be listed as images:

characters formed by consonants and vowels, a website composed of such

characters, and the black-and-white arrangement of text in this critique. The

web indeed serves as the medium connecting all these steps, but what we sense

ultimately returns to images. Even Berners-Lee’s choice to add two slashes

after “http:” purely for aesthetic reasons reflects how important visual

perception is. In this sense, the previously mentioned “era of the web” can be

regarded as synonymous with the “era of images.” When the web is reduced to

images, it becomes an attractive visual experience, which is particularly

emphasized in the works of Yehwan Song.

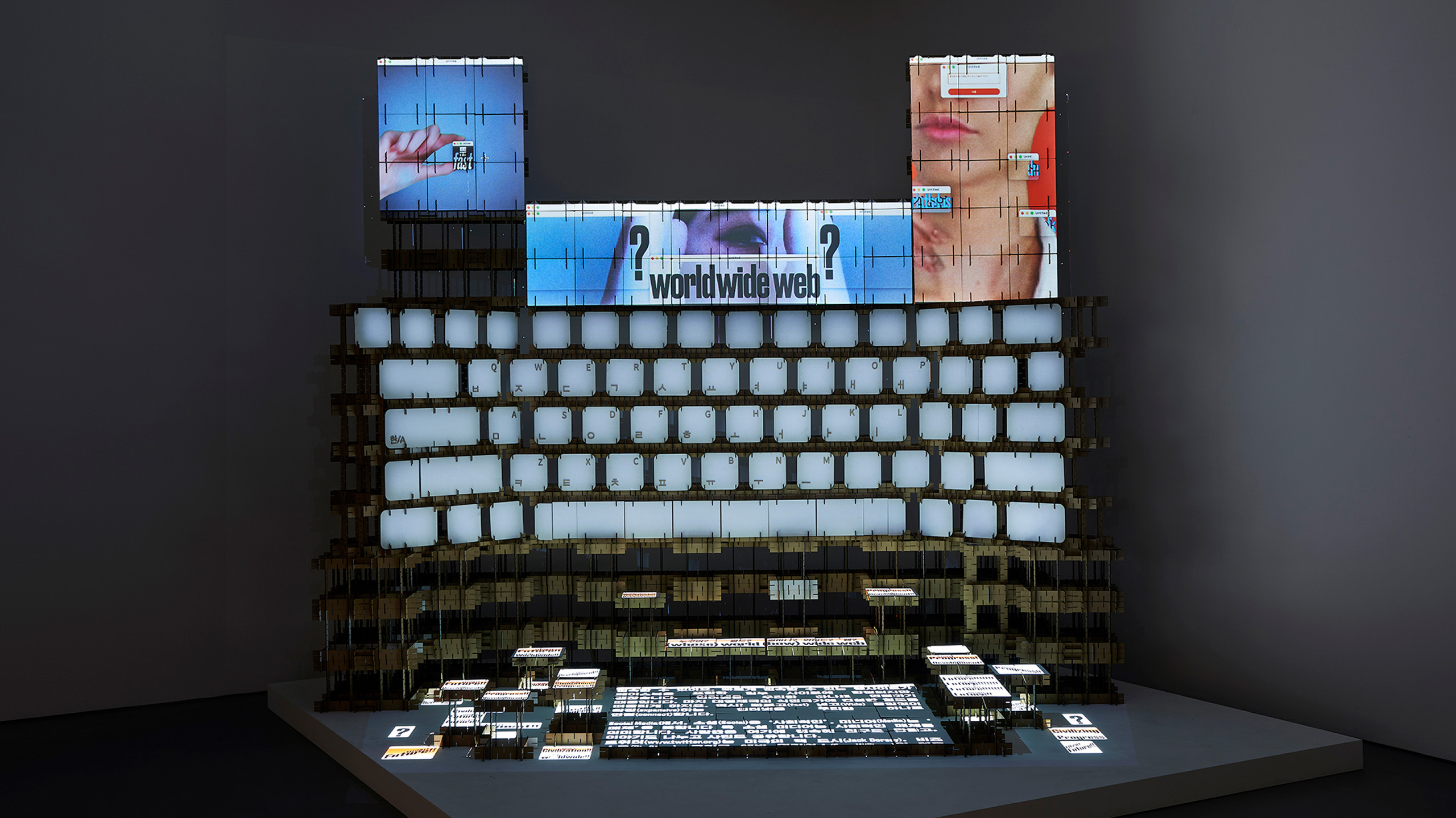

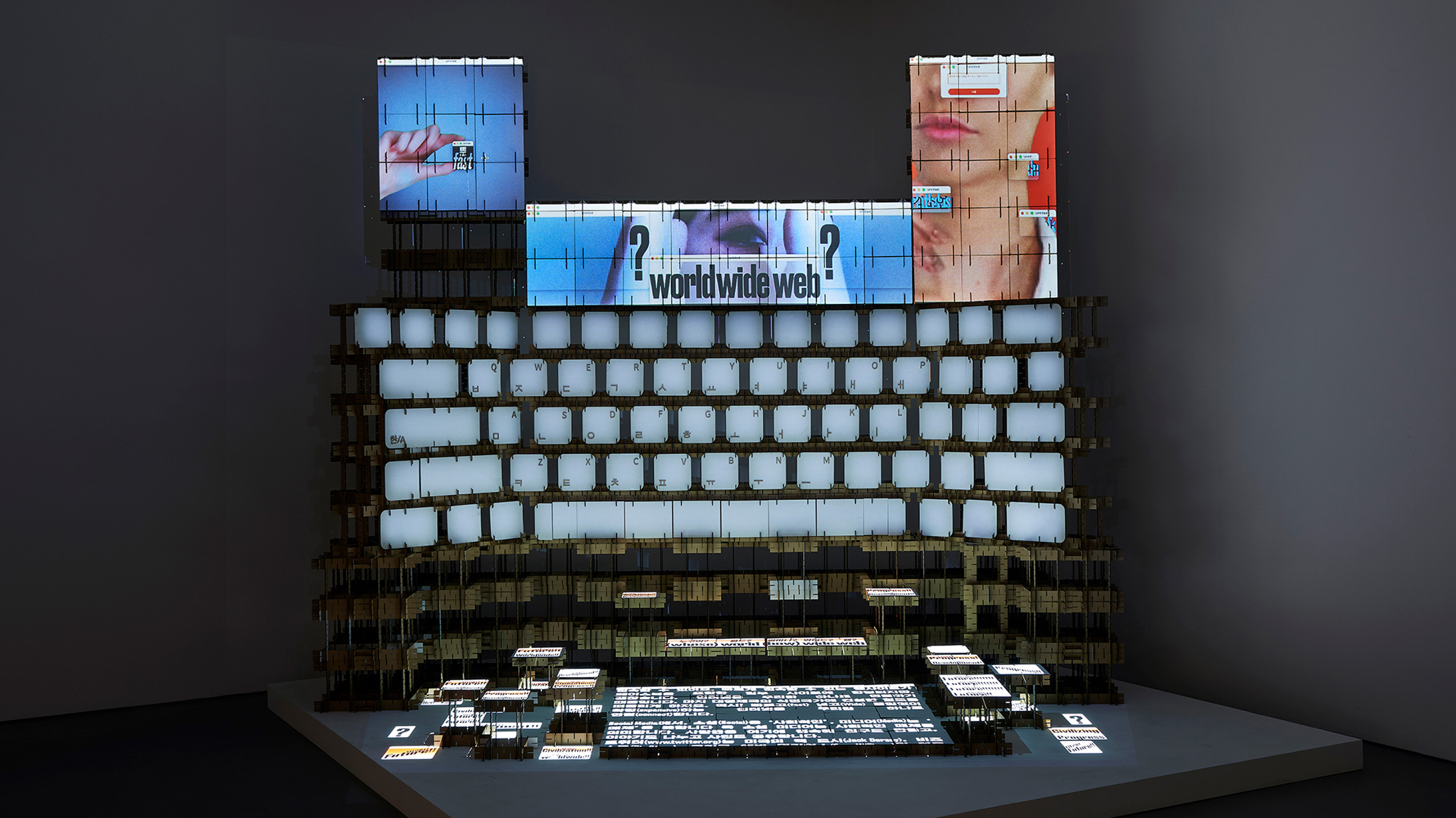

Yehwan Song is a web artist who first became interested in web

design by observing how website designs change depending on the user’s

environment—whether they are using a smartphone, laptop, or tablet. The reason

she is referred to as a web artist rather than a web designer lies in the

embedded messages within her designs and the insights drawn from her affection

for and observations of the web. Even before creating artworks in the form of

web-based pieces, she experimented with original web productions through

digital posters and web design, attempting to establish direct interaction

between users and the web through gesture-responsive web interfaces.

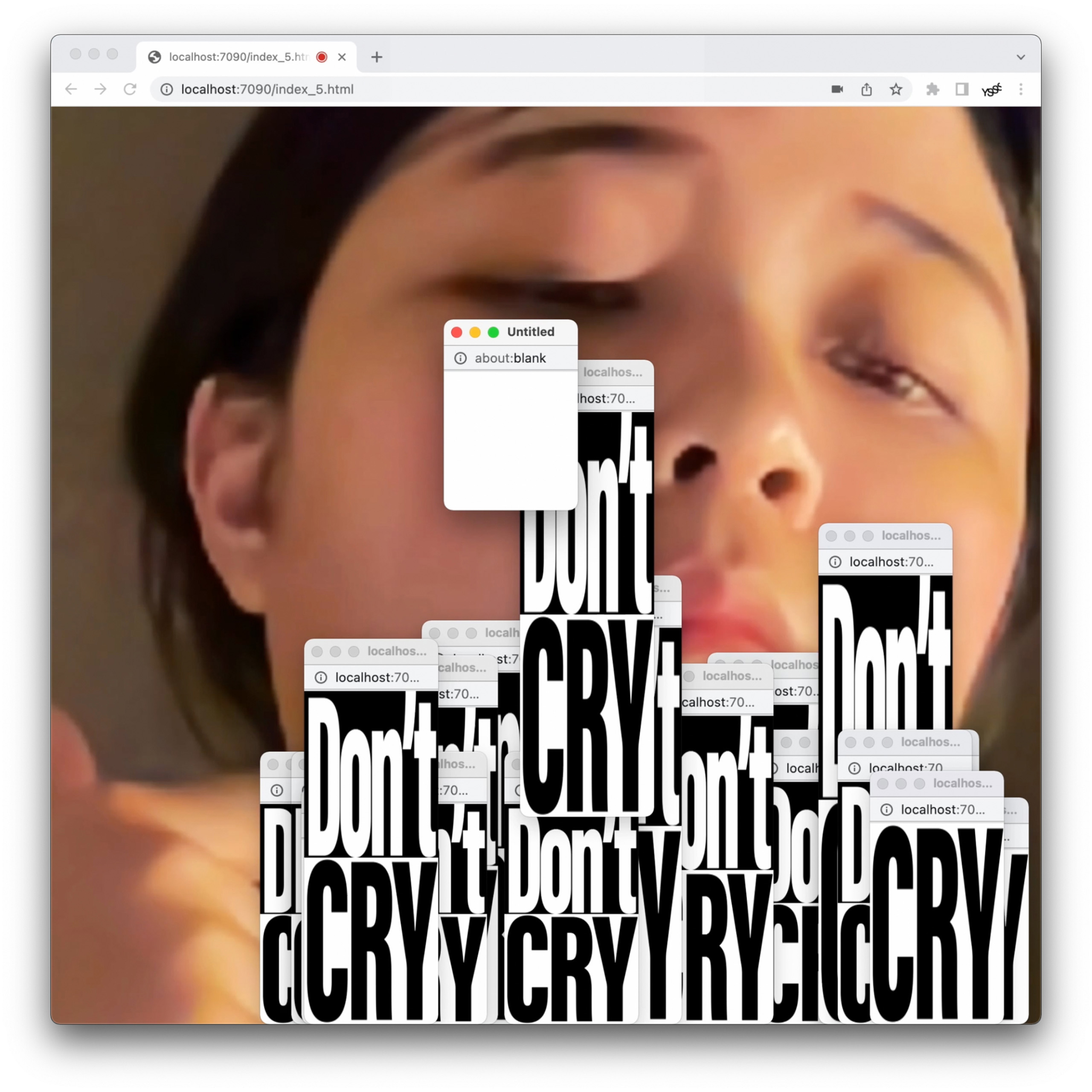

When one swipes from the eyes to the cheeks with a finger, either

"Cry" or "Don't Cry" appears. The more the gesture is

repeated, the more web windows stack at the bottom of the screen. This entire

performance unfolds within a web environment that Song has engineered herself,

as seen in her web performance Cry Don’t Cry. In addition to

this piece, Song has produced other interactive web performances such as Speak

Don’t Speak, where the size of one’s mouth determines the display of

“Speak” or “Don’t Speak,” and Soft Pocking, where shooting

water from a water gun traces white shapes along the water's path on the

screen. Departing from the conventional input-output mechanisms of mouse and

keyboard, Song’s web responds directly to physical movements such as water gun

shots, stick movements, or even unmediated bodily gestures, thereby granting

users newfound freedom in their interaction with the web interface.

Within Song’s works, the web deviates from its conventional form.

It is no longer a means for information retrieval or online connectivity, but

rather serves as a space for private engagement between the web and the user,

producing visual imagery through their interaction. Her independently designed

web pieces function as media that deliver a message, invoking Marshall

McLuhan’s (1911–1980) famous phrase “the medium is the message.” This

proposition draws attention to how media itself alters the world rather than

merely serving as a vehicle for information transmission. Applied to Song’s web

interfaces, her reactive web dismantles the standardized, regulated framework

of conventional web design, promoting an alternative, active Internet

environment that diffuses through diverse forms. Through this, Song critiques

users’ habitual submission to the pre-established frameworks of the web,

unconsciously aligning themselves with limitations without recognizing the

discomfort or constraints imposed by such design.