Question 1: The Shape of “Flat”

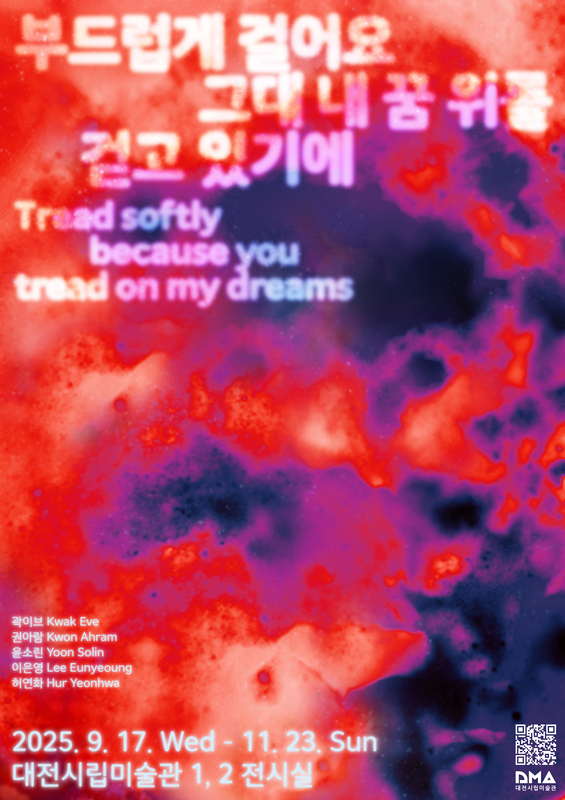

Ahram Kwon entitled her solo exhibition Flat Matters.

When I first saw that title, it was not hard to imagine words like “flat” and

“skin,” which have been much discussed in the art world of late. To be honest,

I also felt the fatigue that comes from ignorance of words and their repeated

use. At the same time, I was curious: why was an artist previously known for

her TV monitor-based video work now referring to the world as “flat”?

The reason I began writing this with a mixture of impressions and questions

about “flatness” is because “flat” is a word that is both familiar and

ambiguous to artists living in the SNS era.1) We can sense what

it is from “the feeling it feels like,” but it is difficult to define. So my

questions about Flat Matters had begun before I

even entered the exhibition venue.

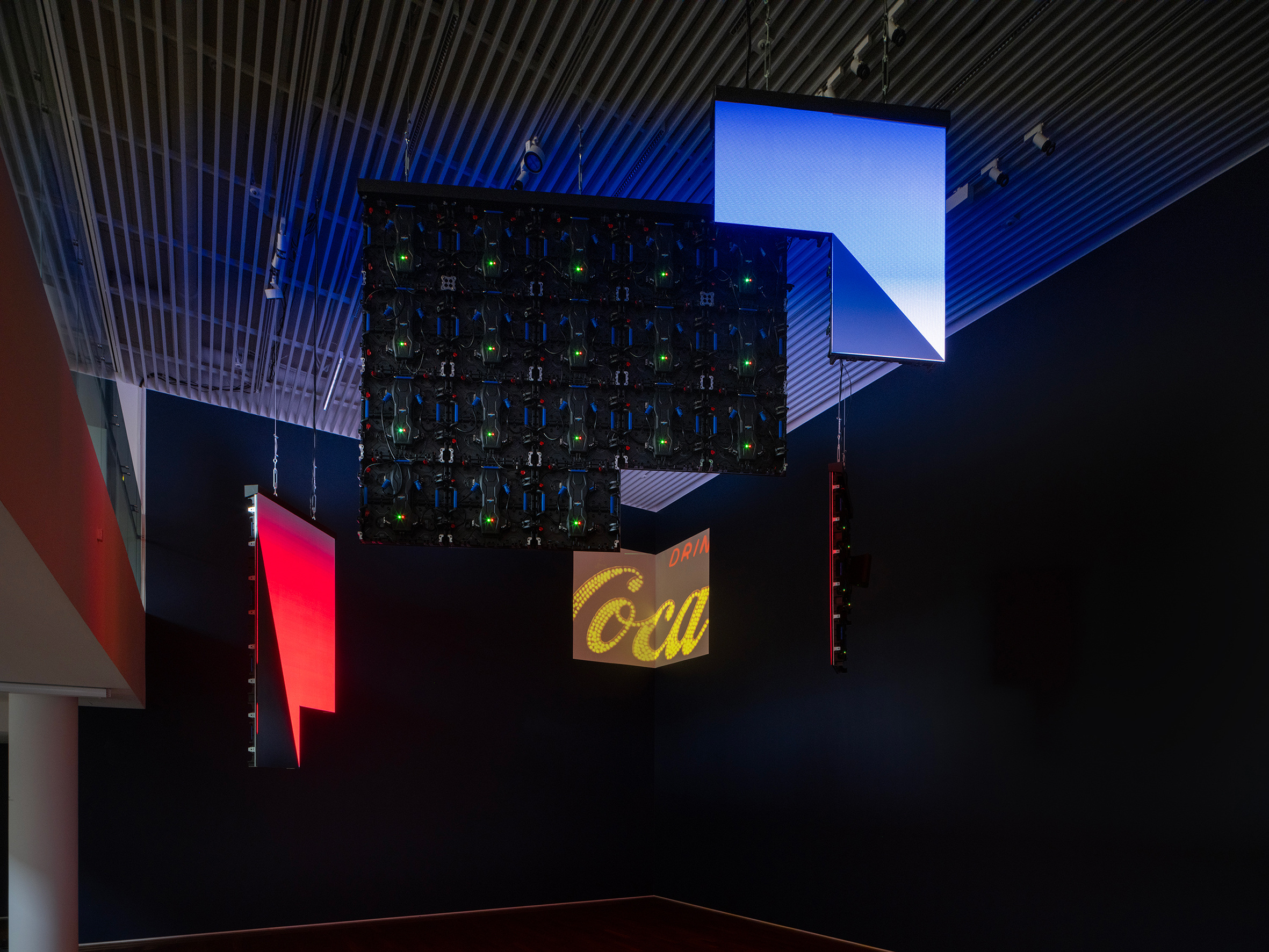

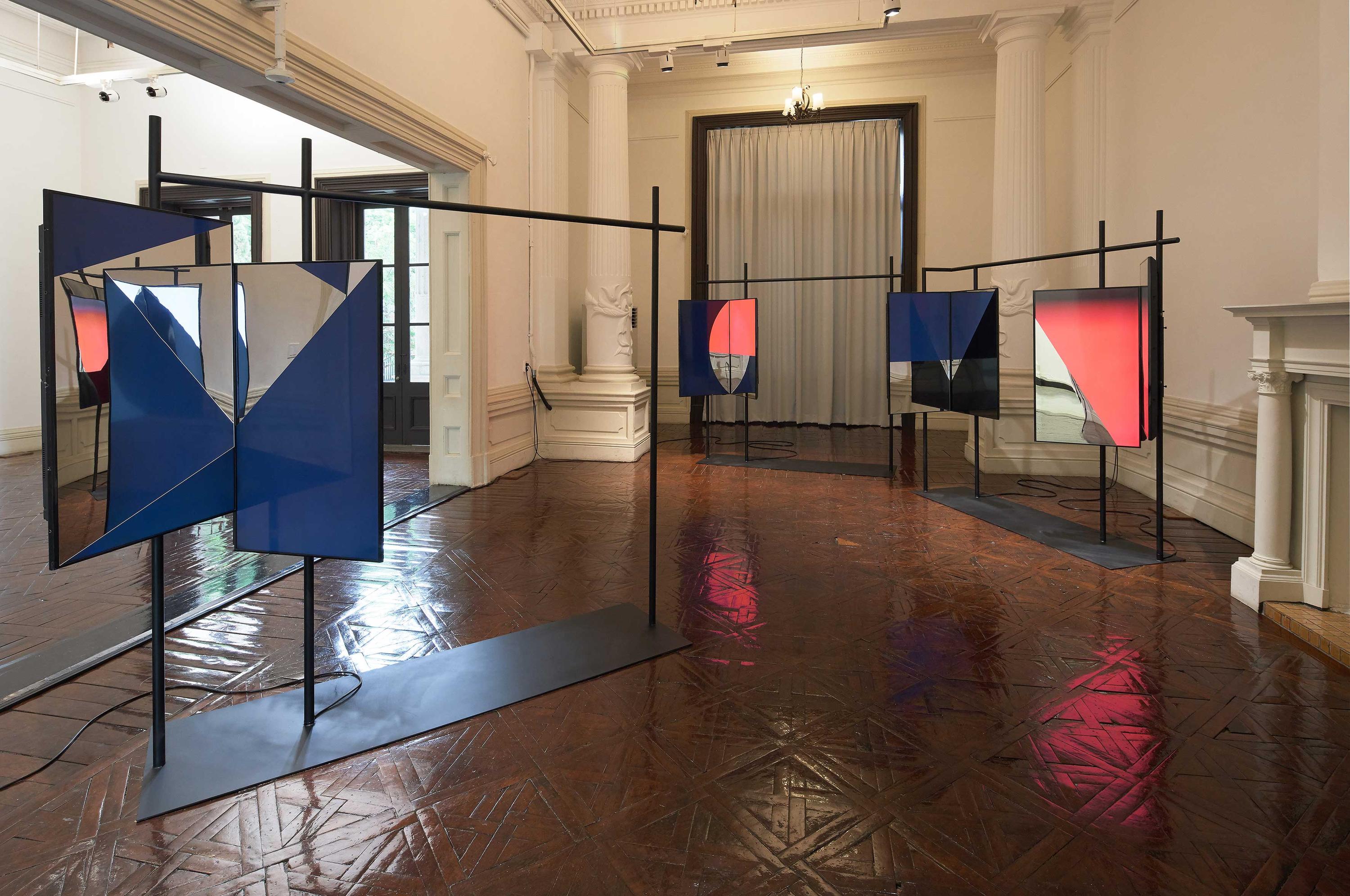

Inside the venue, black monitors are joined, facing each other across the axis

of their edge. But the perception of them “facing each other” has less to do

with the mere shapes into which the monitors have been placed and more to do

with the mirrors which have been cut into triangular and elliptical shapes and

attached to the monitors’ surfaces. Besides showing the facing monitor and the

images displayed on its screen, the mirrors also endlessly reflect the

exhibition space. The images on the black monitors alternate between object

surfaces and red and blue screens, while noises echoing at regular intervals in

the venue seem to be alerting us to some kind of malfunction.

The facing monitors and mirrors reflect each other -- or jostle with each other

for space. What results is a repetition within the exhibition setting: of two

and three dimensions, of images that are flat and spaces that are not. At this

point, we may ask some additional questions. What are the meaning and shape of

“flat” to the artist? And where does the “flat world” lie?

Question 2: The Bare Face of the Surface

In the past, Ahram Kwon has used the video medium to address the issue of

words. Failures at forming relationships with the world due to linguistic

clashes have led her to the issue of translation -- as in The

ashes of words (2013) and Words in fragments (2014),

based on her own experiences of being unable to communicate overseas because of

language differences. Words without words (2015)

uses a translation device to show English and Korean versions of the original

German text of Goethe’s Faust. Obviously, the sentences

do not make sense, but through this very ambiguity they gain a symbolic quality

-- at times reminiscent of avant-garde poetry. Thus, while the words produced

by the translation device are the products of a failed attempt to convey the

original’s meaning, they speak in a totally different language from the

original’s intent. At the same time, the larger world of Faust as a

third language is excised by images of the rock of Sisyphus played across two monitors

and recitation of the translated words.

In this way, questions about words have been a consistent part of Ahram Kwon’s

work. To put it in Derridan terms, questions about words may represent

questions about the world. And because our method of understanding the world is

achieved through words, they also connect with issues of power. The discourse

that constitutes society and its structures are formed through words, and the

hierarchy is determined by how those words are used. But whereas Kwon’s past

works questioned and laid bare the incompleteness of the language defined by

society as a tool for perfect communication, her recent works --

including The ashes of words II (2013), Words

in fragments (2014), Surfaces (2016),

and Spheres (2016) -- see her questioning the

“information” beyond the mirror, using images of symbolic form to experiment

with the ways in which communication with it influences our thought process.

This ties in with the artist’s characterization of herself as posing questions

about the organic relationship of influence between media as human invention

and human thoughts and behaviors.2) Indeed, questions about the

media’s means of transmission are nothing new. Richard Serra presented the

video work Television Delivers People in 1973. To

Serra, the medium of television did not merely deliver consumers, but played

the role of delivering a certain type of consumer by stimulating a sense of

self-consciousness to promote the same market-driven identification between the

community and consumer base. An example of this may be the community and

advertisements shared through media. In connection with this work, David

Joselit referred to the video medium as a “community.” 3)

Ahram Kwon’s work bears clear connections with these pieces, but it does not

direct convey a stance of strident alarm regarding the influence of media.

Instead, she contemplates the relationship between media and consumers through

the repetitious display of metaphorical images, as though giving a “skin” to

the monitors.4) In the Flat Matters series,

the repeatedly displayed images resemble the surfaces of stones or minerals.

Through the images shown on the screens, the viewer naturally imagines and

experiences the texture of the objects. The combination of minimalist screen

divisions and mixtures of colors even have the effect of making the monitors

appear beautiful. It is a case of illusion engendering cognition. But the

sensory activity brought about by the images is deferred as the screen shifts

between red, blue, and black; the mirrors affixed to the monitors further

accentuate the illusion as they pull two dimensions into three-dimensional

space. It is a mixture of real space with the spaces reflected in the monitors.

As this process repeats itself, the viewer is drawn into the various types of

image exposed to them by the media. In this way, Flat Matters constantly

changes its surface.

It may seem like something banal and ordinary for us to be captivated by

regularly moving screens. The artist subtly adds a few devices to confound

that. The blue screens that appear in Flat Matters allude

to the so-called “blue screen of death,” which appears when our computers

experience problems and indicates that some error has occurred. In this images,

the mineral surfaces are mixed with the textures used in digital modeling and

versions created by the artist herself, resulting in something that cannot be

simply defined as an “image of stone”; because of the similarity of the images,

the differences cannot be easily discerned. Unless we have some prior

information as viewers, this image might be simply defined as “stone,” without

our questioning the surface’s bare face. Yet in Flat Matters, these

symbols of malfunctioning seem to operate easily in a well-arranged

environment. Another question is thus raised: Can distrust function before the

liquid crystal screens where so much information is shared?

Question 3: A World of Condensing and Disruption

As mentioned before, Ahram Kwon is attempting to discover the cracks in the

systems society tries to build, seeking to expose their frailty. The way in

which the boundary between real and imaginary is blurred and our thinking

manipulated by the relationship between the information transmitted over

digital media and the consumer receiving it may represent one aspect of the

fissures the artist has seized upon. Constituting rectangles of differing

sizes, digital media have become an essential element for living; it is

difficult for us to imagine their absence. Not having media would lead to a

situation akin to the isolation that comes when one does not speak the

language. But just as words are not truth, so media are not perfect systems for

showing the world precisely as it is. It is becoming increasingly difficult for

viewers to be selective or questioning about the information that media

provide. Condensed packets of information, and thus thoughts that become ever

more fragmentary -- these are what make the world go around.

Ahram Kwon’s questions about surfaces are ultimately questions about the

consumer -- the person looking at the screen. By giving her monitors “skin,”

she calls to mind the position of the viewer unable to distinguish the real

from the virtual. Condensed information is presented before the viewer in

flattened form; flexibility of thought is disrupted (or extended). For Kwon,

the flat world may ultimately be the world inhabited by virtual images

transmitted in two dimensions, and the people who take that information at face

value.

As I perceive the sensual screen produced from the mixture of the monitors’

images, the colors, and the screens reflected in the mirrors, I wonder if I too

am one of the consumers caught in the flat world. Thinking back on it, I recall

that the monitors in the exhibition venue were all arranged in “L” shapes

around the viewers. It may be that we have become beings adrift between

landscapes neither real nor virtual, accepting information without knowing how

to digest it. In that sense, it was quite chilling to perceive myself within

that beautiful yet understated forest of rectangles. But as we approach the

cracks that lie beyond the monitor, constantly questioning -- what kind of

landscape will we then meet?

1) Ppya-Ppya Kim’s What (on Earth) What Is Flat? (1) A Rough Sketch:

Examining Seoul-Flat is a consideration of the recent use of the word

“flat” in the art community (http://yellowpenclub.com/kbb/flatness1/)

2) From the Flat Matters exhibition notes.

3) David Joselit, Feedback (Korean trans. by Lee Hong-gwan et al.,

Hyeonsil Munhwa, 2016, p. 15).

4) From a conversation with the artist.