Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

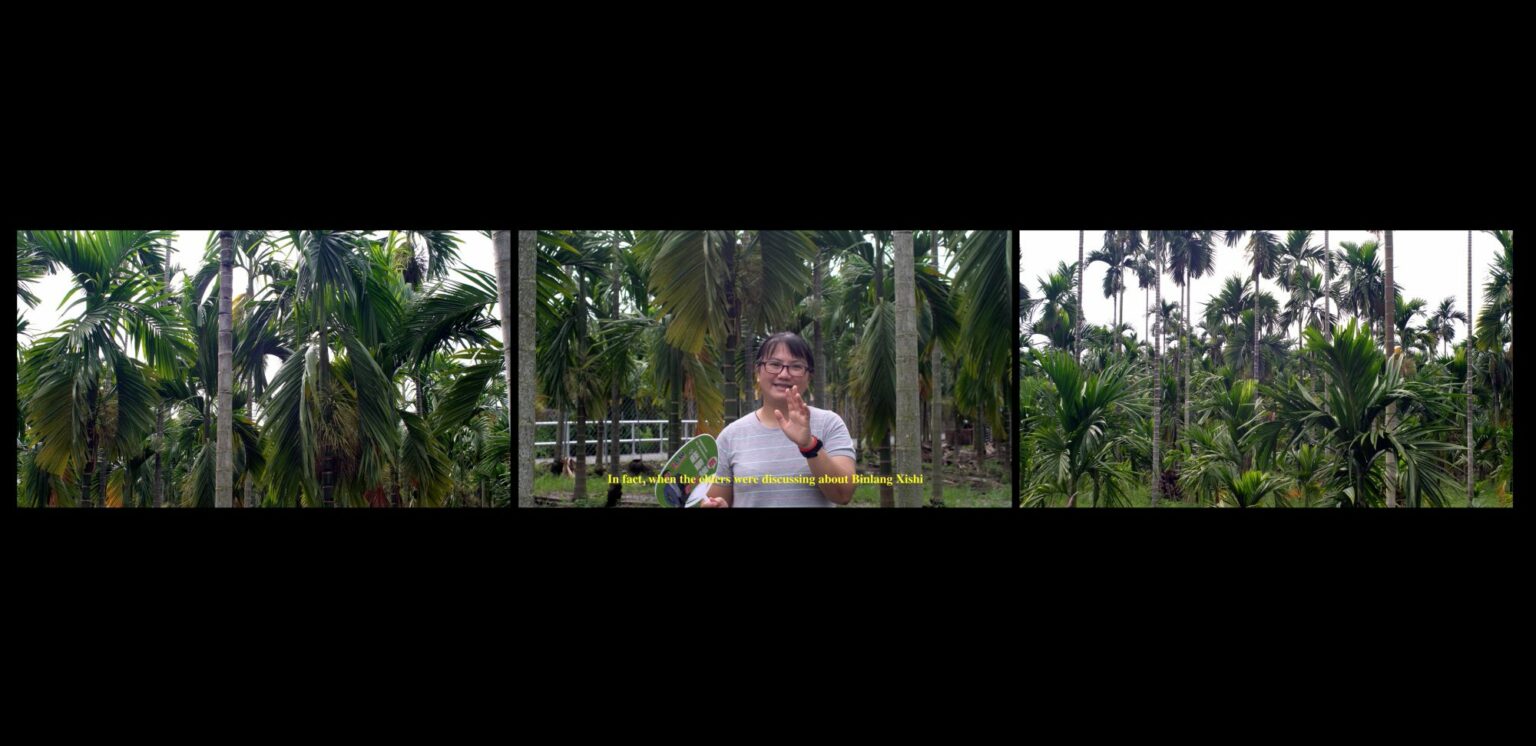

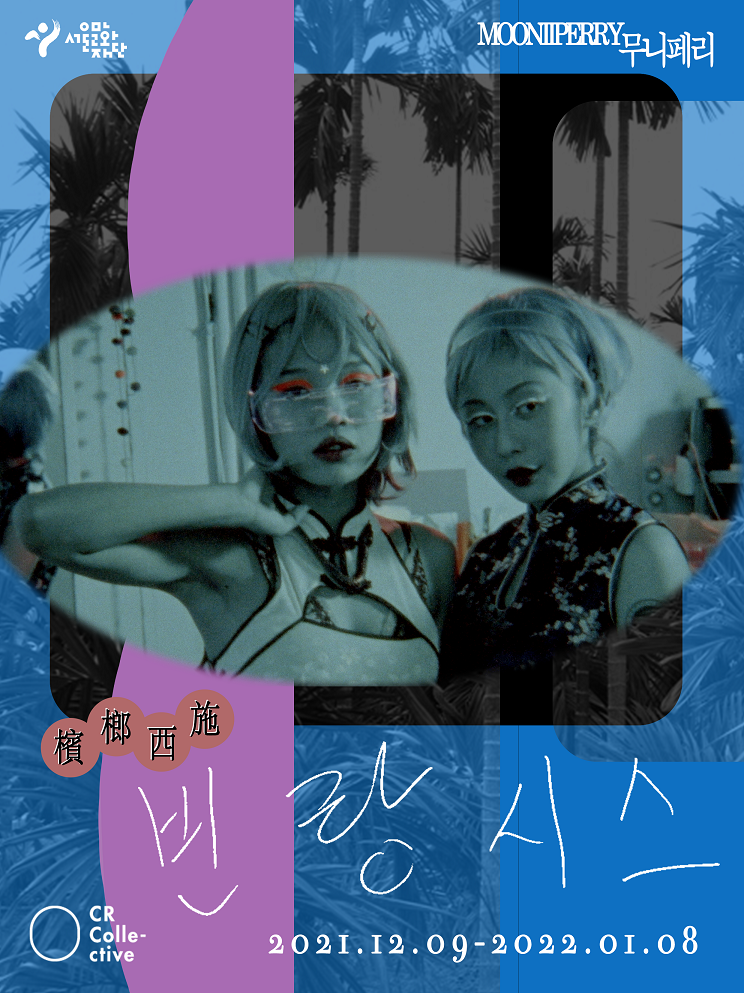

Mooni Perry has held solo exhibitions including 《Missings: From Baikal to Heaven Lake, from Manchuria to Kailong Temple》 (Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, 2024–2025), 《Binlang Xishi》 (CR Collective, Seoul, 2021), 《Mooni Perry》 (Bureaucracy Studies, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020), and 《Transversing》 (Post Territory Ujeongguk, Seoul, 2019).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

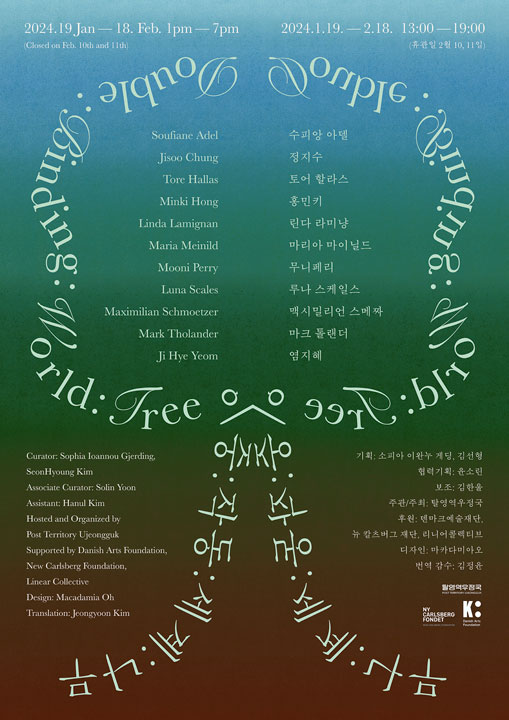

Perry has also participated in numerous group exhibitions such as 《Young Korean Artist 2025》 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2025), 《Double:Binding:World:Tree》 (Post Territory Ujeongguk, Seoul, 2024), the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale (Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul, 2023), 《The Fable of Net in Earth》 (ARKO Art Center, Seoul, 2022), and 《2022 KUMHO YOUNG ARTIST》 (Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul, 2022).