Do you hear the gospel of Cherry Jang?

Truly, this is the era of one-person media. Today, being a BJ

(Broadcast Jockey) or a YouTuber is not just a legitimate career but also a

fast track to stardom, wealth, and social elevation—a path that everyone from

elementary school students to grandmothers dreams of. Covering a wide range of

topics from food, cooking, travel, current affairs, education, lectures, to

ASMR, internet broadcasting has established itself as the most influential and

impactful cultural learning space and a hub for trends in modern life.

Above all, internet broadcasting is no longer the unidirectional

information dissemination controlled by traditional terrestrial broadcasting or

state/public information services operating under the banner of

"credibility." Instead, it is a free, interactive platform where

individuals transmit and receive information according to their own needs,

tastes, and demands.

However, within this platform, countless pieces of information go

unnoticed, and fake news overflows. Stimulating images and information designed

to capture attention, rumors, conspiracy theories, apocalyptic narratives, and

pseudoscience run rampant. Among all media throughout human history, internet

broadcasting has uniquely combined these fabrications with colorful marketing

packaging, creating an enormous synergy—a magical battlefield where fiction

meets marketing.

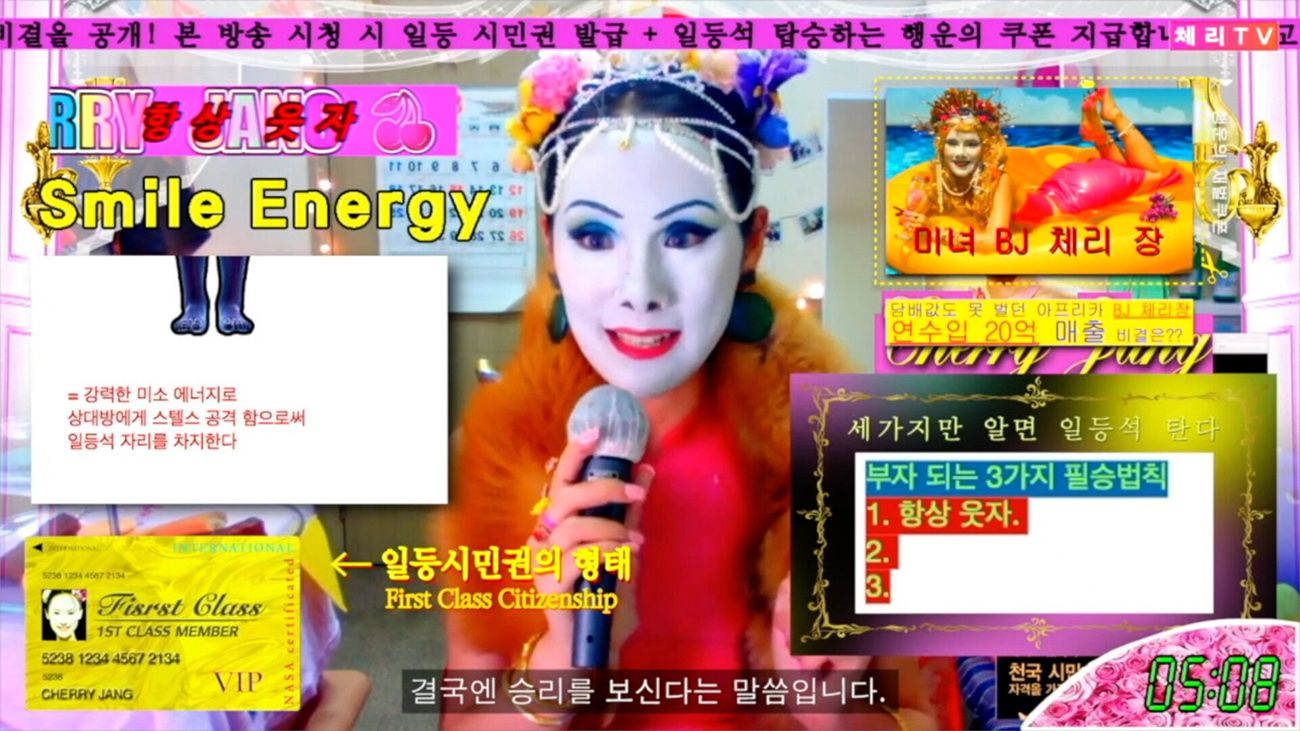

Cherry Jang first gained fame in the art world through the video

work CHERRY BOMB (2018), exhibited in art galleries.

However, she also reaches the public through internet video platforms like

AfreecaTV, YouTube, and Vimeo via her channel "Cherry TV."

The work performed by artist Sungsil Ryu involves parodying the

content production methods of one-person media creators (commonly referred to

as BJs, streamers, or YouTubers) while reproducing the consumption, belief, and

sensitivity of contemporary people as noisy reverberations. Simply put, Cherry

Jang embodies the persona of the fake information and fraudulent online

marketing industry.

In CHERRY BOMB, she declares that North Korea

has launched a nuclear missile toward South Korea and urges viewers to make

payments to acquire "Heavenly Citizenship." With chaotic warning

sounds blaring to signal the urgency of the situation, numerous documents float

on the screen, spewing absurd stories. The excessive subtitles, video clips,

and data visuals—devoid of clear sources or legitimacy—are over-the-top

reproductions of the typical features of fake news videos circulating online.

Cherry Jang’s dark comedy, in which she claims to have received

numbers in a dream, deciphered North Korea’s random number broadcasts, and

analyzed the missile landing spot using feng shui, inevitably provokes

laughter.

While it seems entirely fictional, it actually parodies real

internet rumors and apocalyptic trends. The artist does not merely replicate

conspiracy theories and doomsday narratives but instead exposes the neoliberal

desires and strategies cleverly intertwined with such logic. Marketing

buzzwords like "three principles" or "secrets," which carry

a sense of omnipotence, are propagated as a gospel through Cherry Jang’s

messages of goodwill and love for humanity.