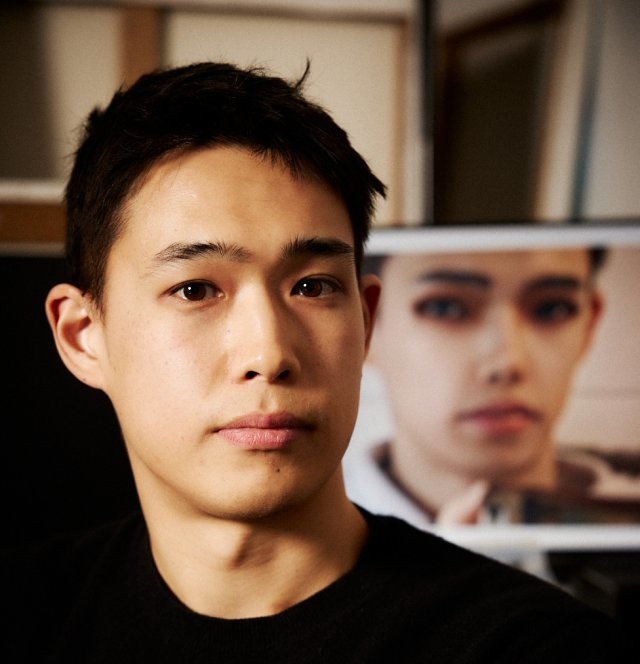

Kim Heecheon (b. 1989) graduated

from the Department of Architecture at the Korea National University of Arts.

He has held solo exhibitions at notable institutions, including Hayward Gallery

(2023), Art Sonje Center (2019), Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, DOOSAN

Gallery New York (2018), and Common Center (2015). His work has also been

featured in group exhibitions at institutions such as the National Museum of

Contemporary Art, Romania; Centre Pompidou-Metz; National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Korea (2023); Nam June Paik Art Center; Gyeonggi Museum of

Modern Art; Busan Museum of Art (2022); Leeum Museum of Art (2021); Atelier

Hermes (2020); and ZKM (2019). Additionally, he has been invited to participate

in major biennials including the Busan Biennale (2020), Gwangju Biennale

(2018), and Seoul Mediacity Biennale (2016). Kim was honored with the Hermes

Foundation Art Prize (2023), the Cairo Biennale Award (2019), and the DOOSAN

Yonkang Art Award (2016). ©Monthly Art

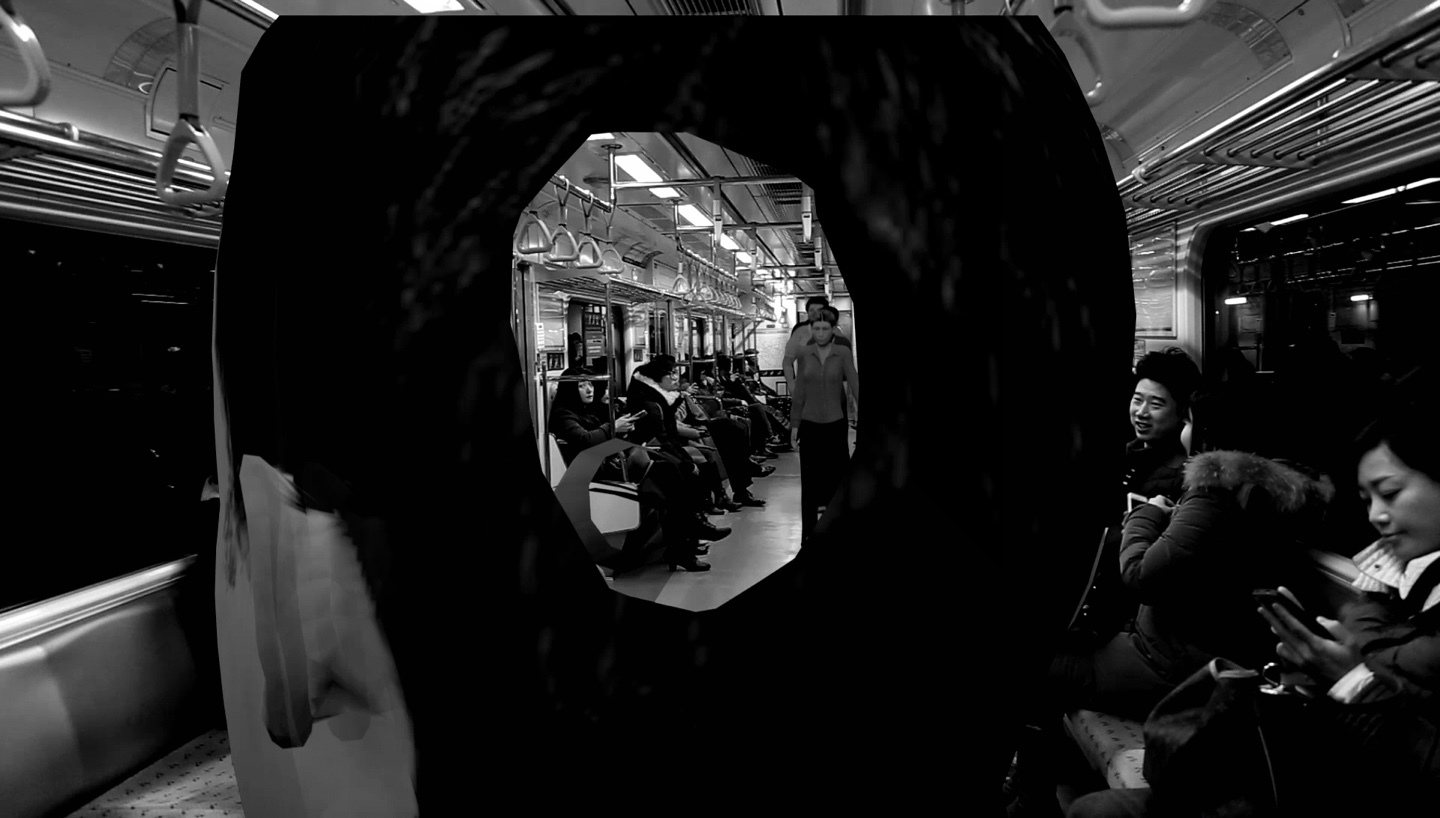

Kim Heecheon investigates the impact of digital technology and

virtual spaces on the real world. Employing digital interface devices such as

3D modeling, face swap apps, and VR, he captures the liminal space that floats

between online and offline realities. His works, characterized by fleeting

images and sounds that quickly vanish from the frame, reflect a form of

"technological adaptation." As a creator who swiftly embraces and

transforms contemporary media, Kim’s screen-based works highlight the shadows of

a digital era that perpetually eludes grasp, engaging with themes of

post-internet art, moving images, and digital media.

Technology, Society, Perception

When Kim Hecheon’s works are played, the agreed conditions and

modes for interpreting society tend to dissolve like fog. In his videos, where

real footage and found footage are manipulated simultaneously, the digital

realm merges with and collides against the physical world. This phenomenon is

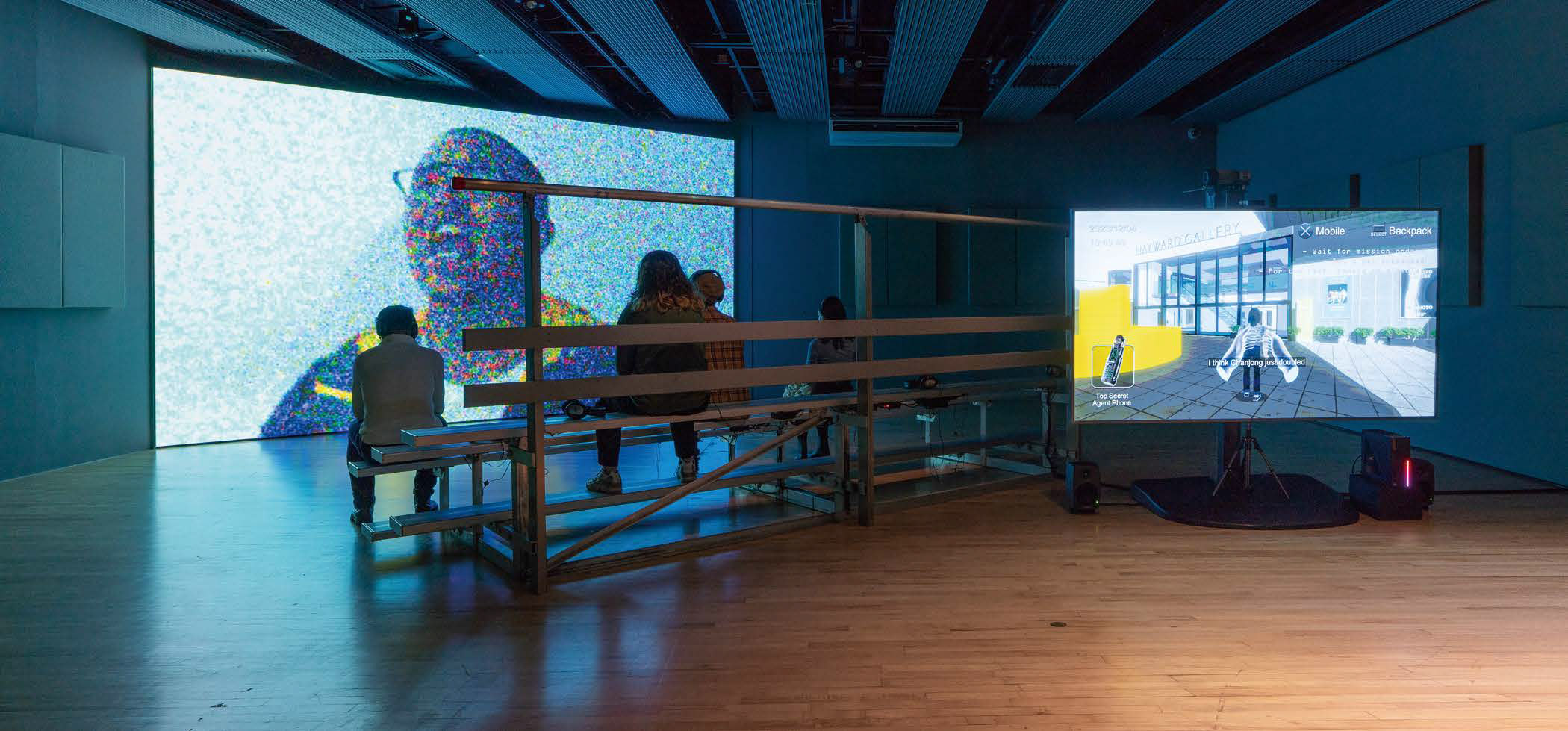

also evident in Kim Hecheon’s first solo exhibition in the UK, currently taking

place at the HENI Project Space at Hayward Gallery, London.

Kim, an artist who has deeply explored the impact of virtual

elements on the perception of the real world through technological experiments

such as GPS, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR), presents two

works in this exhibition: Deep in the Forking Tanks(2019)

and Double Poser(2023). The former was first unveiled at Art

Sonje Center in 2019, while the latter is a commissioned piece and an updated

version of Cutter 3(2023), which was originally presented at

the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s exhibition 《The Game Society》.

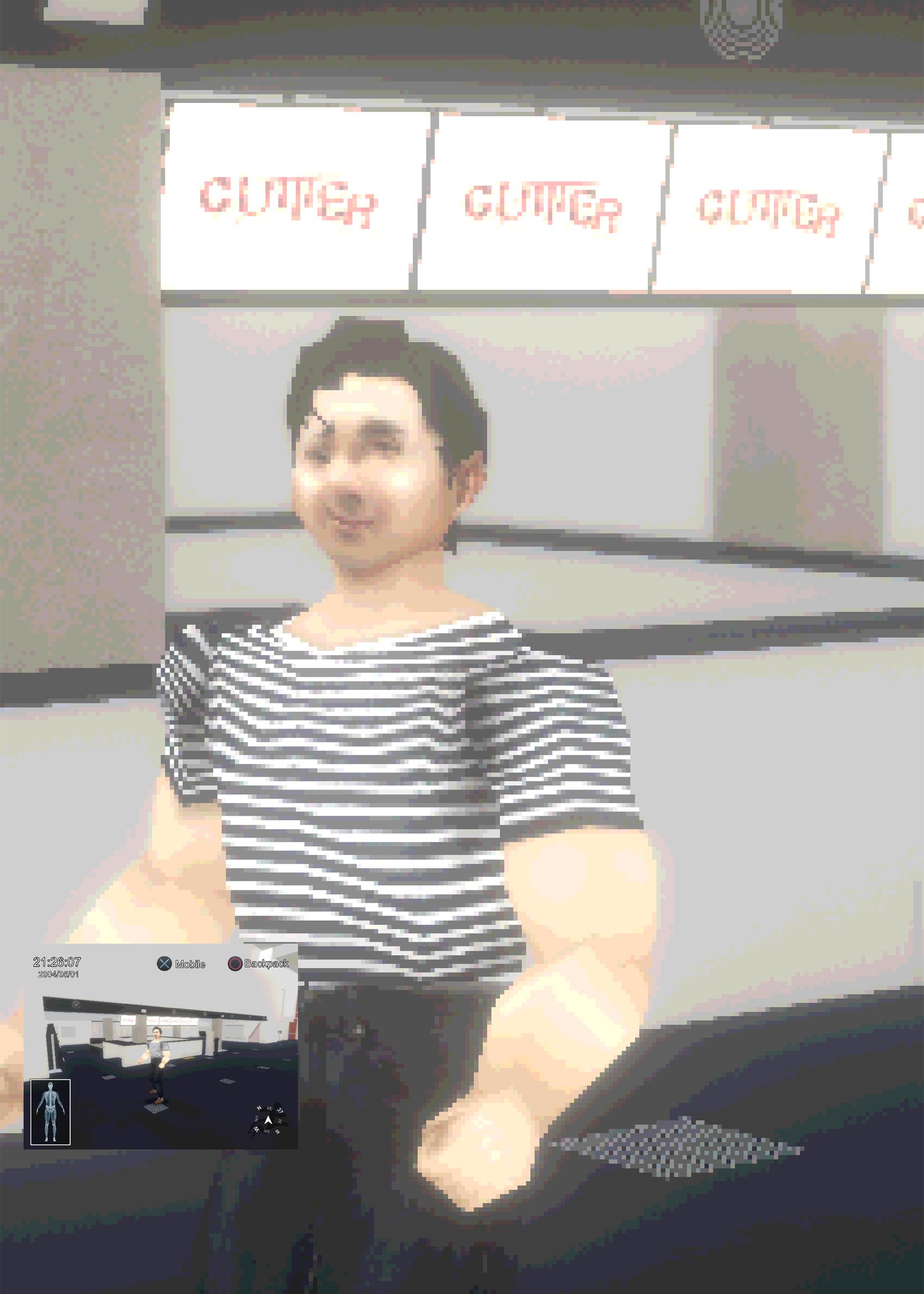

The new work's title, Double Poser, derives

from an English slang term that refers to someone who pretends to know about a

particular subculture but is actually ignorant of it. This concept serves as a

visual clue in the video, which overlaps video game aesthetics with

skateboarding culture. Thus, despite the four-year gap, the juxtaposition of Deep

in the Forking Tanks and Double Poser in the same

space blurs the boundary between reality and virtuality while simultaneously

bringing their coexistence to the surface.

Somewhere, a Phone Rings Looking for Me

There is a character who, while drifting through reality with

complete loss of control, embodies a strange sense of immersion within the

virtual world. The work begins with the sound of a phone ringing, as the

protagonist awakens from sleep. Immediately, he receives specific instructions

from an unknown source: “Stand by for your mission,” “Don’t arouse suspicion,”

and “Act like a mole”—essentially directing him to function as a spy. The piece

soon takes on the format of a video game. After the protagonist leaves his

room, the video’s setting transitions to the actual exhibition site, the

Southbank Centre in London. Completed in 1967 in a Brutalist architectural

style, the Southbank Centre houses the Hayward Gallery. Within the building

lies the undercroft, a space that became a hub for skateboarding culture from

the 1970s to the 1980s. In Kim Hecheon’s new work, this space is meticulously

reconstructed in 3D rendering.

On a fragmented level, the scene acts as a mirror image, yet it is

simultaneously a technoscape—mediated, enabled, and visible solely through

technology. The video, created using the Unity game engine, features a

third-person skateboarding video game interface, a real-time functioning clock,

the protagonist’s avatar, and a pair of translucent floating blue hands. As the

protagonist skates around the Southbank Centre, his hands synchronize with his

movements, while the audience’s movements are partially projected onto the

screen through motion sensors embedded within the work.

The viewer’s perspective oscillates between that of a controller,

a third party, and even the protagonist himself. At one moment, we find

ourselves playing the game; at another, we become passive spectators, as if

watching a professional gamer’s live stream. Occasionally, when the skater

succumbs to boredom and pulls out a smartphone to enter a virtual world, we see

ourselves reflected in his actions. At one point, a visual of birds that

crashed into a glass window at high speed, appearing as if dead, comes into

view. These birds, unable to distinguish between reality and virtuality, mirror

the confused state of humans lost within the screen.

This multiplicity of perspectives inherent within the work

naturally dismantles the possibility of a linear structure. As such, the audience,

faced with fragmented subjectivities, encounters a state of tension between

different identities. In this immersive scenario, the viewer receives an

endless stream of mission commands, devoid of both resolution and limitation,

from the audiovisual information orchestrated by the artist.