"Understanding photographic media, whether old or new, is

completely impossible unless one captures its relationship with all other

media."[1] This statement by Marshall McLuhan, made in passing while

organizing the complex structure of the media world, provides an important clue

for understanding contemporary art mediums, despite being originally addressed

in a different context.[2]

Photography, as the first technical image, distinguished itself

from painting through its ability to objectively reproduce reality, thereby

establishing its unique position. It also facilitated the expansion toward

moving images, such as film and video art. However, aside from the relatively

short-lived modernist pursuit of investigating the nature of the medium itself,

photography has predominantly been discussed in relation to other art forms,

focusing on its value as a record, document, or its ubiquitous usage in popular

culture.

Meanwhile, the "intermediate" position of photography

faced a new phase as the image world transitioned from analog to digital. The

intrinsic capacity for transformation through computer programs disrupted the

"visual truth" guaranteed by traditional photography. Furthermore, as

smartphones and the internet made it effortless to capture and share

photographs, the proliferation of images complicated the task of securing

photography's place as an art medium. It has become increasingly necessary to

discuss "post-photography" more proactively.

Interestingly, the inherent intermediate characteristics of

photography, combined with its transformation into digital images, place it

uniquely within contemporary art's so-called "post" discourse. In the

context of postmodernism—which rejects the definitive, the transparent, and the

singular—photography became a significant art medium alongside the concept of

the "picture."[4]

Following the emergence of new media art driven by digital

technology, contemporary art discourse divided into "post-medium" and

"post-media" perspectives. However, due to its intermediate nature,

photography belonged to both or neither, depending on the viewpoint.[5] As an

art medium enabling moving images after video, it falls under post-medium; as

the starting point of technical imagery transcending the textual era, it

belongs to post-media. To facilitate more effective discussions on photography,

it is necessary to narrow the scope.

In the early 1990s, William J. Mitchell coined the term

"post-photography" by arguing that the physical differences between

analog photography and digital images are fundamental, resulting in culturally

distinct outcomes.[6] Mitchell emphasized that the characteristics of digital

images—appropriation, transformation, reprocessing, and recombination—made

possible through computer technology signify a medium that privileges

"fragmentation, uncertainty, and heterogeneity" while emphasizing

process or performance over the finished artistic object.[7] This concept

naturally connects to postmodernism.

Media aesthetician Norbert Bolz, addressing the transformation of

art through digital media, similarly noted that the methods actively used in

digital images are linked to the postmodern characteristics of playing with

heterogeneity and fragmenting uniformity. He argued that art emerges from

unexpected, non-linear chaos, acknowledging the digital world as a realm of

chance and multiple possibilities.[8]

Meanwhile, the concept of "post-internet" that emerged

in the late 2000s offers critical points from the perspective of image

production and consumption.[9] Rather than perceiving the internet merely as a

technological tool, this concept draws attention to its cultural impact,

proposing that images no longer remain confined to specific media but evolve as

flexible practices throughout contemporary digital visual culture.

Post-internet art particularly emphasizes the

"circulation" of images produced and exchanged through the internet.

It positively views the increasing speed and range of circulation, where

uploaded images can be accessed, stored, transformed, and shared by anyone at

any time. Perhaps this realization aligns with Walter Benjamin's long-held

desire for the "democratic value" of images. However, the essence of

post-internet art lies in expanding the concept of sharing beyond the online world,

contemplating how images are presented in the real world. This consideration

inevitably leads to questioning how digital visual culture interacts with

traditional media and operates within existing artistic realms.

The exhibition 《Super-fine》 at Ilmin Museum of Art addresses the need to discuss the expanded

scope of contemporary photography within the context of such

"post-discourse." Featuring works by nine artists (or teams)

seemingly unrelated, the exhibition presents various artistic attempts to

explore photography's potential in contemporary art, prompting further

discourse on "photography after photography."

True to the subtitle "Light Photography," contemporary

photography has indeed become lighter. Unlike the imposing, large-scale,

meticulously crafted photographs of the past, photography in today's art

exhibitions has become more adaptable, allowing for various presentation

methods according to each piece’s context. Digital technology, which made

large-scale typological photography possible in the 1990s, simultaneously

encouraged the constant creation, transformation, and circulation of images in

daily life, making them lighter than ever.

Especially for the post-internet generation accustomed to the

digital visual culture, such lightness is more pronounced. In particular,

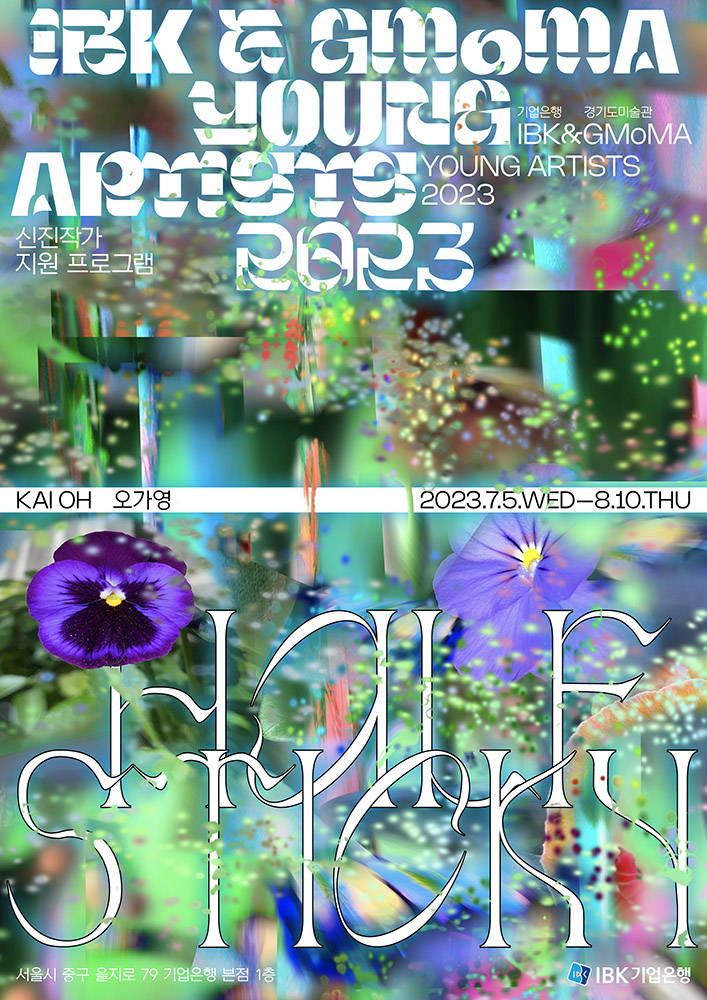

Ogayoung collects countless digital image fragments as naturally as breathing

and reconfigures them through Photoshop in various ways. She prints the

resulting images on paper, incorporating additional materials to present them

as spatial installations. If photography traditionally transforms

three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional plane, the artist contemplates how

to reverse this process.

In the exhibition, she combines printed images with

glass—traditionally a secondary material protecting photographic

surfaces—installing them with hinges and wheels to traverse space. By cutting

out already heavily altered printed images and affixing them to glass or

letting them spill onto the floor, she disrupts the conventional role of glass

as a mere frame component. Instead, the glass becomes an integral part of the

medium, supporting and transforming the printed image into something new.

Digital images bring us into another world. They are no longer

just convenient, novel technologies but have permeated culture as a whole,

becoming integral to our lives. In the realm of contemporary art, manipulation

is no longer viewed as extraordinary or subject to criticism. Instead,

manipulation—reframed as composition—serves as a formal method to effectively

convey ideas and concepts.

In the post-photography era, the notion of "visual

truth" must evolve. Generally, the prefix "post" invites a

reexamination of the original concept, opening possibilities for coexistence.

Discussions on post-photography will not only deepen our understanding of

photography but also expand its scope and potential. Due to photography's

inherent intermediate nature, reflections on the "photographic

medium" ultimately intersect with broader discussions about

"media" within visual culture. It is time to deepen and broaden the

discourse on photography after photography.

[1] Marshall McLuhan,

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), translated by Park

Jeong-gyu, Communication Books, 1997, p. 231.

[2] Originally, the term "media" is the plural form of the English

word "medium," meaning tools or means, commonly referring to

communication tools such as mass media. After the emergence of new media, the

art field began using the plural form "mediums" specifically to

distinguish materials and genres of art. In Korean, the term "매체" (maeche) is commonly used, and this text uses

"medium" interchangeably with "art medium."

[3] The notion of "intermediate" here is derived from Pierre

Bourdieu’s concept of "middlebrow art" (Un art moyen), where

photography is positioned between high art and popular culture, thus not fully

recognized as an art form.

[4] After the exhibition Pictures (1977), curated by the American postmodernism

theorist Douglas Crimp, photography became actively discussed as a contemporary

art medium, along with video, painting, printmaking, and drawing, under the

unified concept of "pictures."

[5] The discourse on "post-medium" began with Rosalind Krauss’s A

Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (Thames

& Hudson, 2000). It primarily emerged among American art theorists,

focusing on the issue of modern art trends dominated by installation art,

advocating for the recovery of medium specificity. On the other hand, the

"post-media" discourse, led by new media theorists such as Peter

Weibel and Lev Manovich, centers on the universal mediality of digital media,

opposing the conventional medium-based perspective.

[6] William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the

Post-Photographic Era, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992.

[7] Ibid., pp. 7-8.

[8] Norbert Bolz, Controlled Chaos: From Humanism to the World of New Media

(1995), translated by Yoon Jong-seok, Moonji Publishing, 2000, pp. 358-365.