Looking Back Retrospectively

Since

everything that can be grasped started becoming an image[1], all images have

aspired to become something that can be tangibly grasped. Let us delve into

this idea more concretely. All things that physically occupy space—like our

bodies—have increasingly become flat images: paintings, analog photographs, and

digital images. Conversely, flat images, in an even shorter time than it took

to become flat and smooth, have returned to being something tangible—like the

illusion of painting, 3D images, and VR images. If these two opposing flows

have progressed in parallel upon the advancement of visual media, what could be

the branching point?

The

reason I find myself reflecting on these thoughts while observing Taewon Ahn's

work is that I perceive his recent works as situated at a point of tension

between opposing forces, continuously moving in opposite directions around a

specific point of action. At either end of this tension lie the contrasting

concepts of flatness versus three-dimensionality, painting versus sculpture,

and image versus object.

When

Ahn’s practice, which initially focused on producing distinct flat-painted

images by layering thin paint on square canvases, began to approach the realm

of sculpture and objecthood, I initially thought his attempts were merely

moving from flatness to three-dimensionality. However, the subsequent works

repeatedly crossed and recrossed that boundary, progressing in directions that

defy simple categorization. For instance, he created sculptural forms that

closely resemble sculptures while persistently retaining painterly elements. At

other times, he abruptly shifted his practice from accumulating digital

image-based painting materials to depicting real-world objects, defying

predictable artistic trajectories.

For

some time, I found it challenging to pinpoint a consistent direction in Ahn’s

work. Eventually, I realized that Ahn views his practice not as a fixed

"state" but as a fluid "situation" in progress. Rather than

being consciously tied to a specific medium, his practice involves adding or

removing elements that correspond to the context of the given moment, operating

within a flexible boundary. At the core of this process lies the

"internet."

The

internet functions as both the environment within which Ahn grew up and a kind

of filter that mediates the perception and output of all media. Encompassing

both virtual experiences and real connections, the internet serves as the

driving force behind Ahn’s continuous practice, which exists amid the tension

between the aforementioned opposing elements. Thus, to retrospectively examine

how Taewon Ahn’s work has evolved to reach its current "situation"

is, in essence, to elucidate the relationship his practice has forged with the

world through the internet.

Drawing What Is Seen

Taewon

Ahn’s early works adopted a purely painterly format by collecting meme images

circulating on the internet and transferring them onto the flat surface of a

canvas. Memes, by definition, are trends or subjects of trends that are

replicated and spread through internet communities and social media by an

indefinite number of people, often through unknown channels and methods. The

lifespan of a meme, which replicates and mutates at an astonishing speed as if

self-propagating, is typically quite short.

What

makes memes significant is not their content or end result, but the way they

are created and proliferate—how often and widely they are replicated and

exposed to the public. However, what first drew Ahn’s attention was not the

underlying dynamics of memes but the visual image that appears on the surface.

He found a sense of enjoyment in the process of painting these rapidly

vanishing digital images onto the canvas.

At

first glance, this may seem like a superficial practice—simply translating a

flat digital image existing in the virtual realm into another flat surface in

the real world. However, the situation changes when we consider that, for

Taewon Ahn, digital images appear more real and tangible than any other

physical object. The intensity and frequency of sensory stimulation provided by

digital images surpass any real-world experience, a sentiment that anyone

familiar with smartphones and the internet can relate to.

In

this context, one might ask: between meme images and flat paintings, which one

can be considered the "flattest" image? Or, between digital images

and the physical "canvas" of painting, which is closer to an

"object"? The act of incessantly encountering images without actively

seeking them—constantly being presented with and subjected to visual

content—reflects our current reality, where digital images become an

inescapable presence.

What

Is Seen Without Intention, The Compulsion of Digital Images. Images that appear

without intentional viewing—continuously presented and flooding in—are a

defining characteristic of our current digital reality. The deliberate use of

the passive verb form “to be seen” combined with the additional passive suffix "-어지다" in Korean underscores the relentless exposure to digital

images that we must constantly face. This linguistic repetition mirrors the

reality of our time, where digital images become an unavoidable presence,

perpetually intruding upon our senses.

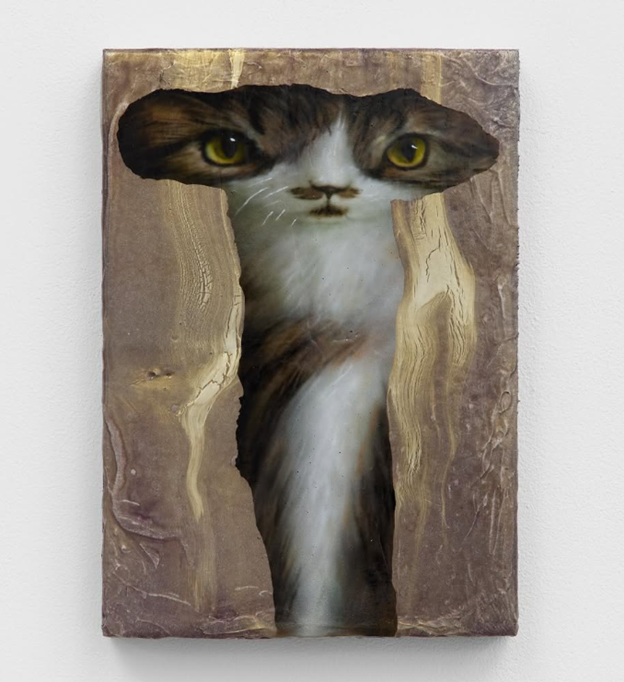

One

of the reasons Taewon Ahn perceived meme images as more object-like lies in his

experimental use of transformed canvases. At a certain point, Ahn began to

alter the very shape of the canvas that held the memes. Rather than confining

the memes to a conventional rectangular canvas—akin to a transparent window—he

began transferring them onto shaped canvases that could more directly reveal

the traces of objects.

For

instance, in works from 2021, Ahn employed canvases that emphasized the

distorted shapes of cat memes, using irregular forms that visually mimic the

meme itself. In another instance, he shaped the canvas to resemble the outline

of a corn cone snack, cutting it out as if directly extracting the meme from

its digital context. This transformation heightened the uncanny realism

inherent in digital images, accentuating their sense of displacement when

translated into physical form.

Up

to this point, I assumed that Taewon Ahn would continue to expand on his

existing data of meme images and further develop his techniques. However,

unexpectedly, one day, he stopped painting memes altogether and began to paint

a real cat.

Drawing What One Wants to See

After

bringing home a stray kitten named Hiro, Taewon Ahn noticed a significant

change in his routine: he spent less time compulsively looking at his

smartphone. Hiro became the focal point of his reality, and it was only natural

that the real cat, rather than internet memes, began appearing in his artwork.

The emergence of Hiro in his practice signaled a profound shift in Ahn’s

approach and subject matter, as the presence of a living, tangible being

disrupted the digital image-saturated reality he had previously inhabited.

The

reason Ahn’s early work fixated more on the surface of meme images rather than

their inherent logic may be because that logic was already deeply embedded in

his consciousness. When he transitioned from drawing what he was constantly

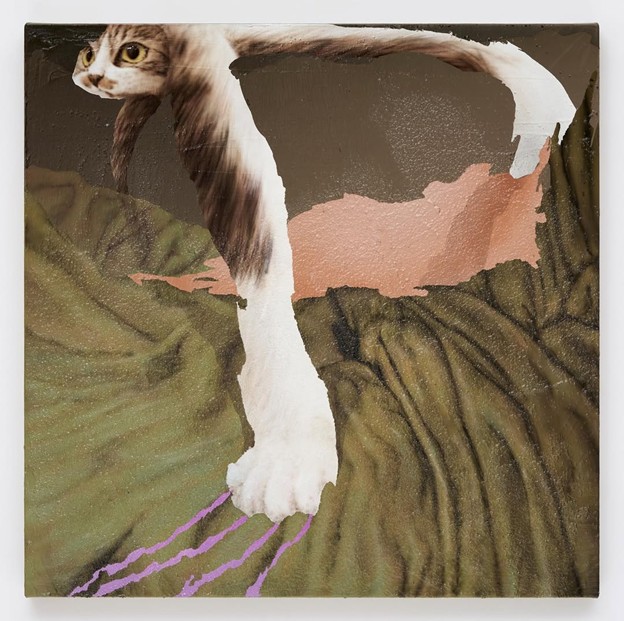

shown to drawing what he wanted to see, he naturally maintained the digital

image’s inherent qualities of reproduction and proliferation. Ahn began

photographing Hiro and treating these images as memes—distorting and

manipulating them before reproducing them on various surfaces (2021–).

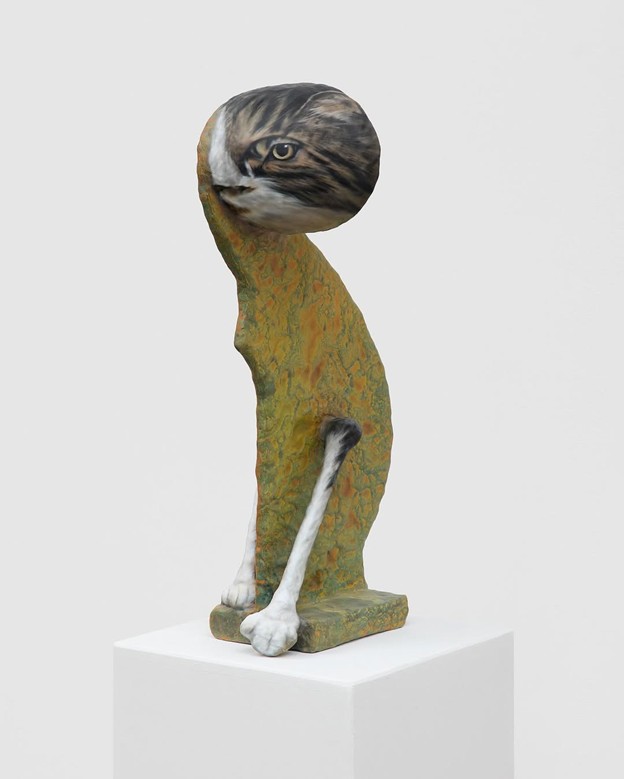

Here,

the term “various surfaces” refers to the unconventional three-dimensional

objects Ahn started creating alongside his flat works. Despite their

three-dimensionality, these objects still functioned as “surfaces” because he

continued to apply the airbrush technique he used on canvas to these sculptural

forms. The only differences lay in whether the surface was flat or curved, or

what object served as the base for his paintings.

Through

this period, Ahn honed his skills in realistic depiction using an airbrush, a

tool initially suited for conveying the sleekness of digital images but equally

adept at realistically portraying the physical presence of Hiro. Despite the

distorted forms of his sculptures, Hiro’s representation became increasingly

lifelike. This raises an intriguing question: although Ahn’s works have moved

from flat canvases to sculptural forms, is it still valid to view them as

fundamentally planar if he remains fixated on their surfaces and the

superimposed images?

Why,

then, is Taewon Ahn so fixated on the surface of objects? His persistent

engagement with the surface—whether flat or textured—suggests that he views the

surface itself as a critical interface between digital and physical realms.

Ahn’s sculptures, though three-dimensional, seem to retain a flatness inherent

in his airbrushed imagery, blurring the boundaries between painting and

sculpture, surface and volume, image and object.

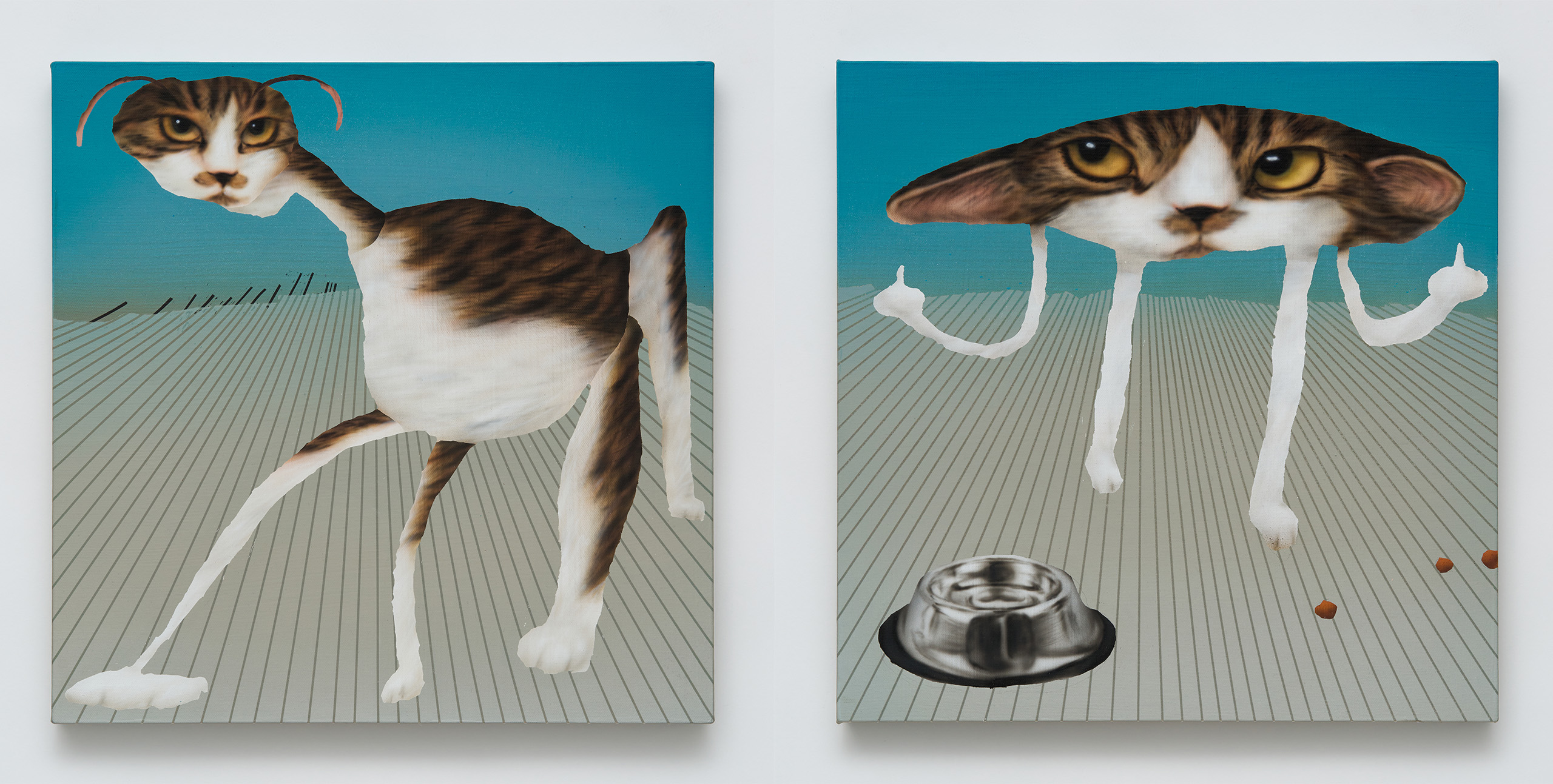

Flat-Painting-Image and Three-Dimensional-Sculpture-Object: 《PPURI》(2024)

The

solo exhibition 《PPURI》(2024) highlights how the internet, deeply rooted in Taewon Ahn’s

identity, manifests in his recent works. The title "PPURI" (meaning

"root" in Korean) hints at the exploration of the fundamental aspects

of his creative practice. As viewers enter the exhibition space, the first work

that catches their attention is a large-scale canvas (200 ho) positioned on the

farthest wall opposite the entrance. The painting features a distorted image of

Hiro, the cat, rendered on a uniquely textured surface that Ahn has been

experimenting with recently. This piece sets the thematic tone for the

exhibition, where distorted and exaggerated forms challenge the viewer's

perception.

Surrounding

this central work are twelve sculptural pieces scattered throughout the

exhibition hall. These objects continue Ahn’s exploration of translating Hiro’s

real physical presence into painted "images" on sculptural

"surfaces." However, these sculptural works are not merely paintings

transferred onto objects; they possess a volumetric form that seeks to become

sculptural entities in their own right. Ahn’s latest endeavor to create

pedestals for these sculptures exemplifies this approach.

Unlike

conventional pedestals that simply support objects, Ahn’s custom-made bases

seem to act as extensions of the artworks themselves. They function as

structural supports for forms that remain inherently incomplete—image-objects

that have not fully matured into independent sculptures. The pedestals thus

serve as a metaphor for the transitional state of Ahn’s works, where they waver

between being two-dimensional images and fully realized three-dimensional

sculptures.

Through

the juxtaposition of distorted paintings and sculptural objects, 《PPURI》 emphasizes Ahn’s ongoing exploration

of the duality between flatness and volume. The works evoke the hybrid nature

of Ahn’s artistic identity, shaped by digital visual culture but deeply

connected to physical, tangible realities. By crafting pedestals that

physically sustain these hybrid forms, Ahn underscores the idea that his

creations are not static objects but dynamic, evolving entities. The exhibition

ultimately portrays Ahn’s artistic process as one of continuous transformation,

where surfaces serve as a point of convergence between painting and sculpture,

image and object.

On

the other hand, the sculptures presented in this exhibition feature sculptural

gestures where their surfaces are finely and intricately carved. These newly

layered interventions on the previously completed sculptures reveal a

substantial amount of manual labor. By stripping away the surface of the

finished objects, Taewon Ahn aimed to expose the inside of the image rather

than merely creating a visual effect. This act can be seen as an effort to

increase the contact surface of the image—physically engraving tactile gaps on

a seemingly untouchable surface.

The

traces left by the sprayed sculptures on the white walls of P21 reaffirm that,

although Ahn’s works are image-based, they are undeniably oriented toward

objecthood. These flat-painting-images, which now embody

three-dimensional-sculpture-objects, reflect Ahn’s hybrid identity shaped

through the internet. As an artist who has internalized the grammar of digital

images, Ahn continues to strive to create a form of "object" despite

the inherently flat nature of his images.

If

we view Ahn’s works not as fixed “states” but as works situated in specific

“situations,” the distinction between painting and sculpture, or flatness and

three-dimensionality, becomes irrelevant. His practice has, from the very

beginning, taken the form of images rooted in objects. The question then

arises: What kind of form will the image’s body take next? It remains uncertain

what kind of material form these infinitely variable images within his practice

will assume in the future. However, as he continues to approach everything once

again from a perspective of "materiality," it will be intriguing to

see what crossroads his work encounters.

[1]

In this text, the term “image” refers to something that imitates, reproduces,

or records a representation of reality, while distinguishing it from language

and objects.

[2] The word "meme" originally derives from the word

"gene," signifying a self-replicating characteristic. In his book The

Selfish Gene (1976), Richard Dawkins used "meme" to

describe ideas, beliefs, or cultural structures that, like genes, possess

replicative qualities and are passed on from one individual or group to

another.