1. What Will Be Drawn and How

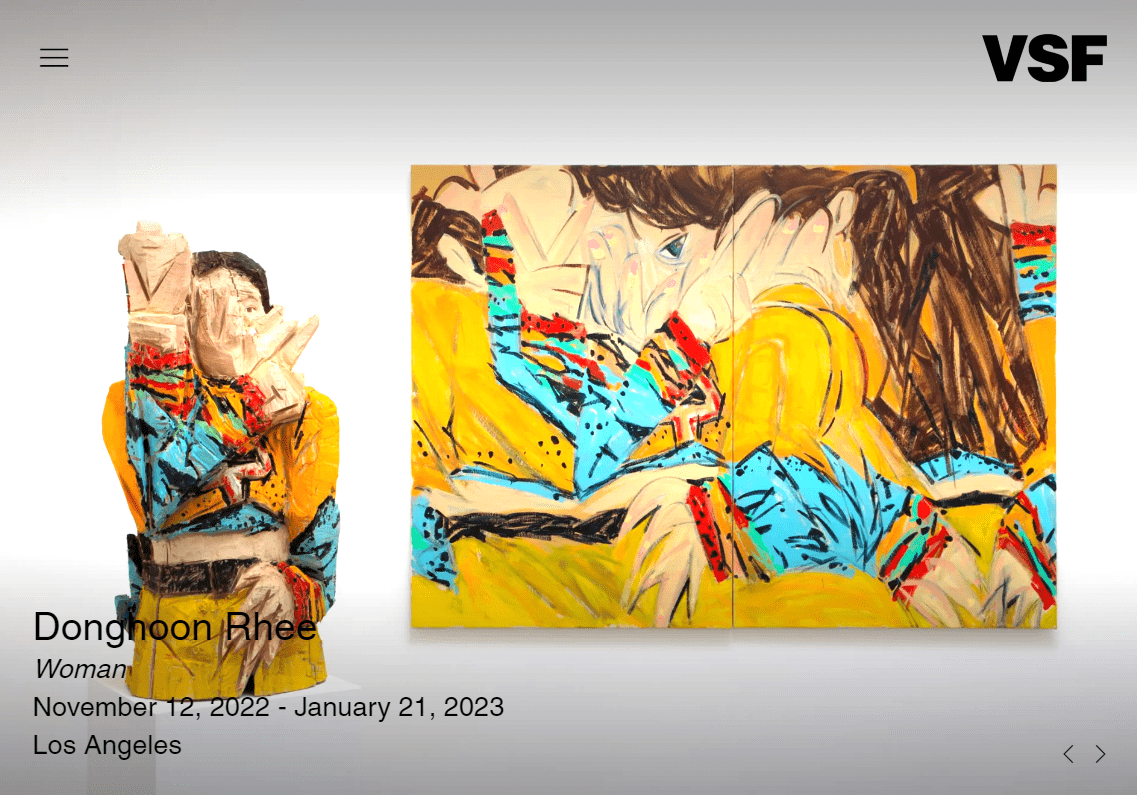

The wooden sculptural works of

his that I remember have rough surfaces that are neither sufficiently polished

nor fully colored. The sculptural forms, which look as if they have been

summoned from a tree trunk standing in the ground with a sincere gaze, support

a three-dimensional sense that rotates in the verticality of a cylinder. The

characteristics of this spiral structure have been generated through classical

norms of (human body) sculpture, establishing the ideal aesthetic conditions

for a form to automatically stand upright on the floor.

It seems that following such a

three-dimensional sculptural ideal, Rhee Donghoon reflected on the idea of

painting in his deep mind. He seems to have explored objects that can be

considered contemporary painting alongside experimenting with the close causality

between an object and a form. This is somewhat predictable through an

experimental approach between creative conditions and forms that was displayed

in the early stages of his painting before he began sculpting in earnest.

He initially worked on the

question ‘What will be drawn and how’. Over two years from 2015 to 2016, he

deduced a proper form by using literature as his painting theme and adhered to

his role as a faithful performer. For instance, in his work 〈Makar Devushkin’s Boarding House〉 (2015),

based on Bednye Lyudi (Poor Folk,1846) by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

(1821-1881), Rhee Donghoon portrayed the character’s boarding house on a flat

painting surface by overlapping acrylic colors and a printed image. It seems

that this was to establish the logic of his painting method by swiftly

identifying the visuality of today as encapsulated by digital images with the

reality of periodic contradictions as depicted in Dostoevsky’s novel.

Returning to recent work in which

he is already fascinated by wooden sculpture, with 〈Makar Devushkin’s Boarding House〉 unfolding

before us, the surface gives the impression that the boarding house is

well-organized on the rectangular screen, albeit being fragmentarily arranged

in parallel. Given the structure of the screen at this time, it seems that the

painting was completed by overlapping the layers of coloring with acrylic after

printing on canvas began from the form of the pillars positioned in bilateral

symmetry. The ornamentally carved pillars clearly produce symmetry on the

screen as well as the frontality, as if (re)verifying the obvious fact that

Rhee Donghoon’s painting was attempted on a two-dimensional plane. This can

also be said to be his aim to indirectly emphasize the painting frame, which

became blurry in (his/today’s) painting.

Rhee Donghoon stopped formal

experiments with literature painting for about two years after this, during

which time he clearly realized the contemporary task of taking it upon himself

to renew the formal logic of painting, thus revealing more directly his

interest in the canvas frame.

2. The Supporter for New Painting

〈Let’s See Who’ll Win〉

(2017) has the meaningfulness that can be the threshold between his early

painting and recent wooden sculpture. He stated, “I bestowed diversity upon the

canvas by making it myself to emphasize information of the materials, and I

drew a cat on it.” Partially implied in his early painting, the physical

visibility of the painting frame was by now fully fledged; furthermore,

depending on the form of the canvas, he continued to seek a method to draw an

object effectively. For instance, 〈Let’s See Who’ll Win〉 shows unusual variation in being glued with pieces of canvas cloth

around the frame of the canvas. He arranged the parts of the painting as if

misaligned puzzle pieces to be ‘logically’ perceived rather than be experienced

‘visually’. A cat is drawn on the canvas pieces glued along the frame of the

three-dimensional square structure with the center-left open. Nevertheless, he

showed his impulse to renew the pictorial screen following the surface of the

support by crossing between the plane and the three-dimensional structure

(relying on the logic of the bare canvas structure). He also aimed to raise the

possibility of the pictorial screen interlocking with changes in the support.

Actually, following 〈Let’s See Who’ll Win〉, Rhee Donghoon already

experimented with work that directly indicates his recent wooden sculpture. He

drew a cat on the support, fully revealing the physical structure of the canvas

frame. He then illuminated the status of the subject matter ‘cat’ in order to

experiment with the close connection between the canvas form and the painting

style by abandoning the painting theme or the subject matter content

established on the screen. At this time, Rhee Donghoon carved a cat shape in

wood and covered it with canvas, upon which a cat pattern had been drawn. He

merely spoke of “the pleasure of drawing objects of his affection” with

emphasis; in fact, his statement almost suggests that his painting subject

matter (at least the cat) doesn’t determine any style or content. That is, the

mediation of the (canvas) support and (painting) materials merely justifies the

drawing. It seems that he tried to find a new painting support and pictorial

surface that could interconnect with them.

Rhee Donghoon carved a wooden cat

sculpture, used it as the canvas support, and covered it with painted plain cat

patterns (like skin) interconnecting with the support form. Likewise, the

synchronization of his wooden sculpture and canvas painting was done quite

closely but randomly. It was mutually mediated as an action molding a cat as a

familiar shape without any meaning. Given this context, rather than seeking a

separate approach to the medium, it can be surmised that he has simultaneously

undertaken sculpture and painting as a process of hypothesizing and verifying

to intensify the (dubious) relation of the two in the pictorial context.

It can be said that he

unexpectedly began working on wooden sculpture in earnest. He endeavored to

verify his hypothesis on the formal relationship between the physical structure

of the canvas frame and painting on canvas, and he learned woodcraft with the

intention of making picture frames by himself. He learned woodcraft from a

master, envisaging frames that embody aesthetic qualities in themselves, in

addition to being gorgeous ornamental frames that could function as painting

frames. Although he trained in wood-carving skills, he didn’t even try to make

wooden frames initially. Interestingly, he carved flower forms by looking at

the real flowers that would also be used for still life. This is how his wood

carving began.

3. Still-Life Sculpture for

Painting

By the time he was devoted to

learning woodcraft, he planned to copy a masterpiece on flowers from world art

history. As a result, it seems that he began his flower carving with the goal

of ‘copying’ a masterpiece and ‘copy-carving’ a frame. With great timing, the

third result relating to the painting style that he sought was also deduced.

Rhee Donghoon’s sculpture has a

few characteristics to emphasize: using wood as a material; making a large

chunk form using an electric saw and a chisel instead of expressing detailed

contours and textures; coloring the surface of the sculpture suitable for the

real object; and mainly dealing with the forms of plants, animals, and human

bodies. His early work, which was made by carving wood into an appropriate size

so that a vase and flower pot could be placed atop as a prop, was produced as a

still-life sculpture that was ‘possible to paint’ or ‘to be painted on’ from

the beginning. This work spun off into two performances, one to clarify that it

was possible to add pictorial practices like coloring or painting to still life

as the physical support for a painting like a canvas frame; the other that

still-life sculpture as an object of copying challenges pictorial possibilities

in which a three-dimensional object is interpreted like a plane on a typical

canvas screen.

In 〈Flower Pot〉 (2018) and 〈Vase〉 (2018), early works colored with

acrylic after being carved from a log, he continuously exposed the original

form of the wood for emphasis (as if revealing the canvas structure in detail

as he did before). In particular, in 〈Flower Pot〉, the cylindrical pot, the flower rising vertically up and the

awkwardly repeated rhythm of the cylinder’s spiral structure have a distinctive

mass through harmonization with the leaves of the pot and the shadows, which

make the sculpture autonomically stand upright alongside being

three-dimensional. That is an arbitrary contour, but looking at the work

closely, you can catch another intriguing spot. On the surface, which the

artist peeled with a saw and a chisel, horizontal and vertical patterns are

continuously repeated. It gives the impression that the faces ‘contain’ a

certain form rather than the shape of a flower elaborately carved and endlessly

intersected. So to speak, they are like two-dimensional supports for the form.

By using the wooden sculpture to support the painting, Rhee Donghoon finally

painted flowers connecting to the support structure.

He frequently produced still-life

sculptures with flower pots and vases as the subject matter from 2019. He also

added new subject matter such as animals and plants, as seen in the works 〈Flamingo and Grass〉 (2019), 〈A Cat, a Titmouse, and Grass〉 (2019), and

others. By reconfiguring various different subject matter like a collage, he

also produced sculpture faithful to the material of cylindrical wood, such as 〈A Long Cat 1〉 (2019) and 〈A Long Cat 2〉 (2019).

For instance, in the case of 〈Vase with Magnolia〉 (2019), he carved a

black vase incongruently up and down in the middle (like baldly revealing the

spiral structure as if to avoid making it look too flat), and greatly

emphasized the pictorial effect of the flower and leaves in the intersection of

rectangular faces as he painted the cat form like a puzzle in 〈Let’s See Who’ll Win〉 on the brim of the

canvas through revealing the canvas structure. In particular, (in the form of

the sculpture) the leaves in the vase are simply carved, almost achieving a

cuboid shape, and painted with yellowish-green and brown on each face through a

shading effect, enabling the concreteness of the object to be revealed on the

pictorial surface rather than the sculptural form.

The height of 〈Flamingo and Grass〉 is 164cm, and the upper

part and lower part of the sculpture are divided as if two separate wood

materials have been connected. The body of the flamingo is placed on the upper

part of the sculpture, and the legs and grass covering the surroundings are placed

in the lower part. Similarly this time, it is obvious that the cylindrical wood

was carved around the wood in three-dimensions, which is also emphasized

through the coloring effect, which is maximized with the rectangular faces

alongside the shading and perspective through the pictorial hallucination on

the surface.

Thus, instead of making the

picture frames, Rhee Donghoon decided to ‘copy-carve’ the painting subject

matter with a technique that he had learned to make picture frames, and he used

the wooden sculpture he carved as a painting support like a canvas plane and

painted with colors suitable for the objects. This was done through the subtle

intersection of sculpture and painting, copy-carving and copy-painting, and the

supports and content.

4. Still-Life Sculpture and

Sculpture Still-Life

In his first solo exhibition, 《Indoors

with Flowers》 (2019), Rhee Donghoon moved the still-life sculpture that he

carved onto the canvas. This action that moves roughly (three-dimensional)

forms to (two-dimensional) colors addresses the question that he was clearly

aware of from the beginning: “What will be drawn and how?” As he changed and

produced a canvas structure that was visually revealed and painted with cat

shapes on the shredded canvas screen from an early stage, (with a bit of

exaggeration) it seemed that he secured some space for painting by assessing

and trimming the wood according to its form. It must have been an effective

solution that satisfactorily answers the question ‘What will be drawn and how?’

I guess that he found another unexpected painting support in three-dimensional

sculptural form by going through several processes like this.

Meanwhile, ‘sculptural painting’

presents another answer to the same question. He experimented with how colored

still-life sculpture can be transferred to a flat canvas as a painting object

corresponding to ‘what’. For instance, after 〈Vase〉 (2019), still-life sculpture colored

with acrylic paints on wood was completed, going through pictorial

transformation with acrylic paints on canvas as if forming another antithesis.

In 〈Vase 1〉 (2019) and 〈Vase 2〉 (2019), he drew part of the

still-life sculpture 〈Vase〉

almost resembling the sculpture by looking at the same position. This time,

completed as “still-life sculpture”, the independent 〈Vase〉 was summoned as an object for painting with a size of 53cm in width

and 45.5cm in length to become the “sculpture still life” to be drawn. The

pictures painted by observing the still life are 〈Vase

1〉 and 〈Vase 2〉. And the screen of 〈Vase 3〉, another painting version, is greatly expanded to a size of 145.5cm

in length and 112cm in width, and layers of yellow paint on the surface of the

painting are covered like fog.

Introducing such works in the

exhibition 《Indoors with Flowers》, wooden

still-life sculptural works were placed on the prop while paintings imitating

the sculptures were displayed side by side to target each other like reference

points. He didn’t reproduce all of the still-life sculptures through painting,

but it is clear that the close and potential relation between sculpture and

painting was established. In particular, an intriguing gap between the two is

simultaneously revealed. That is, the still-life sculpture is the same as

explained above, but the painting drawn on canvas with that as an object shows

quite a different approach from the sculpture.

〈Vase 3〉 is reminiscent

of the context of his early work in which he covered the surface of the carved

cat shape with a cat pattern drawn on the canvas. Between the acrylic coloring

on the three-dimensional surface of the wooden sculpture and the picture

painted on the side of the sculpture with acrylic paints on the canvas, subtle

differences among the circumstances connecting each are visually contrasted.

Rhee Donghoon carved delicate surfaces on which the colors change depending on

the outside contour as well as light and shade, as if sketching in preparation

for painting by keeping in mind the surface color. Rather than giving a

realistic three-dimensional effect, his still-life sculpture is reminiscent of

a molding process series in which the face of a form is perceived that depends

on the chroma as well as the shade of the form. On the other hand, in the

process of transferring the sculptural work to a two-dimensional flat canvas,

Rhee Donghoon painted it to look flat and even, as if being pressed by eliminating

the sense of space, the cubic effect, and the feeling of distance thus evenly

spreading the perspective. That is, as he arranged each side with the chroma in

a row when he painted the surface of the wooden sculpture, he transferred it to

a flat canvas by emphasizing pictorial hallucination through the chroma.

His experimentation continued

after producing the still-life sculpture that was carved following still life

and colored on its surface, and the still-life painting that was transferred

onto canvas from sculpture. This continued after 〈Vase〉 (2020), 〈Magic

Lily〉 (2020), and 〈Cactus〉 (2020) by undergoing pictorial experimentation through the

combination of three works under the title 〈Untitled〉 (2020) on one flat canvas. The work continued to highlight the

“abstract” color plane that was greatly emphasized in still-life sculpture,

grafting pictorial hallucination on the sculptural support.

5. Sculptural Continuity

and Pictorial Continuity

In his second solo exhibition, 《Sculpture

also Dances》 (2021), Rhee Donghoon wholeheartedly introduced human figures

that he had begun in 2020. With his human figure sculpture focusing on costumes

and the choreography of K-POP idol groups, he understands the object as a new

body combining with specific costumes as well as a new norm of

three-dimensional human figures established through specific choreographic

movements.

The work 〈Not Shy〉 (2021), a sculpture of a dancing

human body as it is revealed visually, has a structure in which the lower body

replaces a prop abstractly trimmed from a log, atop which an upper body

expressing a dancing movement is placed. Rhee Donghoon displays an interesting

attempt to express a body as it is without any movement, and the hands and arms

move rapidly depending on how the choreographic movements are piled atop one

another. This continuity doesn’t reflect the time-based description of the

conventional, spiral structure. He reflects no-time-based continuity that

resembles digital editing rather than construction using continuous movements

logically and transparently through overlapping body movements.

Such sculptural renewal was done

through pictorial trials, which indicates that Rhee Donghoon’s sculpture and

painting are closely connected. In this case, as well, the process of

transferring still-life sculpture slightly changed into sculptural still life

to a flat canvas, and the (renewed) continuity of the sculpture is converted to

pictorial continuity through maximizing the pictorial effect in 〈Not Shy 1〉 and 〈Not

Shy 2). In the process of transferring the still-life sculpture created by

carving a cylindrical log to painting, Rhee Donghoon engaged an important

device. He placed the sculptural still life on a rotating roller and drew a

picture by looking at the rotating object rather than the stationary one. By

renewing the sculptural logic on the continuity of movement while carving a

human figure in continuous dancing movements, he gained the definitive

appropriateness of transferring it into painting. It can be said that it was

not (old) time-based. This is descriptive continuity, but non-time-based continuity

that implicates visual sensibilities through digital editing and technology

within the media conditions of today’s sculpture and painting. The two

paintings leave room for continuous adjustment and imagination within and

without the painting grid, the juxtaposition of the fixed image, and the

endlessly swaying virtual image through (self-designed) sculptural reference.

In 2022 New Rising Artist 《Explorer》, he again

showcases still-life sculpture with flower pots or vases as the subject matter

and pictures painted from sculptures. Having experimented with the referential

continuity of painting and sculpture through human figure sculptures, Rhee

Donghoon returns to the plants that he has dealt with from the beginning. He

stood himself before the question ‘What will be drawn and how?’ by

concentrating on the process of carving and transferring the carved objects to

canvas painting.

〈Anemone and Delphinium〉

(2022) is a still-life sculpture produced by carving ginkgo wood and coloring

it with acrylic paint. The first impression is that of the remains of a

sculpture placed on the prop, the outline and the mass, with the rest having

been severed like a head sculpture that has been cut horizontally at the neck.

The sculptural works even convince us that they could be continuously changed

through exchange with other props or other forms. That is the formative feature

seen in most of the still-life sculptures displayed for this exhibition, such

as 〈Delphinium and Oxford Scabiosa〉 and 〈Calla and Clematis〉, which have been placed without props on the floor.

Each still-life sculptural work

presents formative characteristics that he has shown from the early stages, but

by and large, the features compromising or connecting the voluminous sense of

sculpture to the pictorial surface can be estimated in 〈Cactus〉 (2022). So to speak, Rhee Donghoon

secured the faces for coloring by ironically “flattening” the sense of

sculptural volume, and the faces are again circulated in the sculptural volume

sense. This is repeated in the 〈Delphinium and Oxford

Scabiosa〉 (2022) and 〈Alstroemeria,

Carnation and Oxy 1〉 (2022) paintings. Placing the

completed still-life sculpture on a roller and repeatedly painting it

horizontally while rotating, Rhee Donghoon began enumerating pictorial faces

with colored ones that were mobilized for a sense of sculptural volume. The sculptural

support disappeared and the surface of the sculpture spread on the flat canvas

doesn’t hesitate to be converted into a pictorial colored face.

Rhee Donghoon’s painting and

sculpture, in which sculptural references and pictorial references intercross,

make viewers focus on “painting” when reaching the final stage. Also in the

wooden still-life sculpture, the sculptural support is explained as a structure

for experimenting with pictorial possibilities, to be reestablished as objects

for painting again. And this is meaningful in tuning to instrumental

possibilities rather than reaching for completion in the style of his work.