Last year, the armful or so of Korean pine I’d amassed felt like

dots, scattered here and there through my workshop. Take away one section, and

another would appear. The paintbrush, gliding over rough, bumpy terrain, led to

color. The materiality of the wood was apparent as it was, and also glimpsed

between the sparse coats. To observe the object, we use the eye; for the act

itself, we enter the form of the body, diving into the mass. It is thrown.

Having worked with relatively heavy materials, I feel like I have developed the

know-how to sustain this practice. The situation having grown slightly stiff,

it was necessary to try something different. Both materially and

methodologically, I think lightness was what I wanted.

Preparing for the exhibition, I chose specific performances by

H1-Key, SHINee, New Jeans, and NCT DREAM. I collected recordings made by all

different kinds of cameras, from official broadcasts to fan cams to dance

practice footage. This soil — constituted of so many different versions edited

in different ways — is rich; and accessing it is both easy and fast. I observed

the images, sequenced over a saved timeframe. The ever-changing lighting of the

stage contrasted with the performer’s hair, makeup, and costuming, creating

moments of exquisite kineticism. One by one, I picked out the things that

intrigued me: the colors, the expressiveness of a fingertip, the details of an

outfit.

Paper, to me, was a new material. It occurred to me that paper

might be a more interesting medium for dealing with the dynamics and movements

of K-pop idols. Using acrylics, I played with the hues and contrasts of the

performances I was referencing, using an underpainting brush to create colored

paper with visible strokes that reflected a sense of speed. From a dot-like

mass to a line that cuts across a flat surface — a transformation. There were

volumes and contours only possible via knife and scissor. The change in

material led not to another partial removal, in the manner of the tool and the

body, but rather a transformation into process: namely, the process of pasting

pre-prepared sections together. Along the way, the bending, wrinkling, and

folding tendencies inherent to the paper naturally found themselves fixed —

with pins, tacks, glue, and wire — following the dynamics of the choreography.

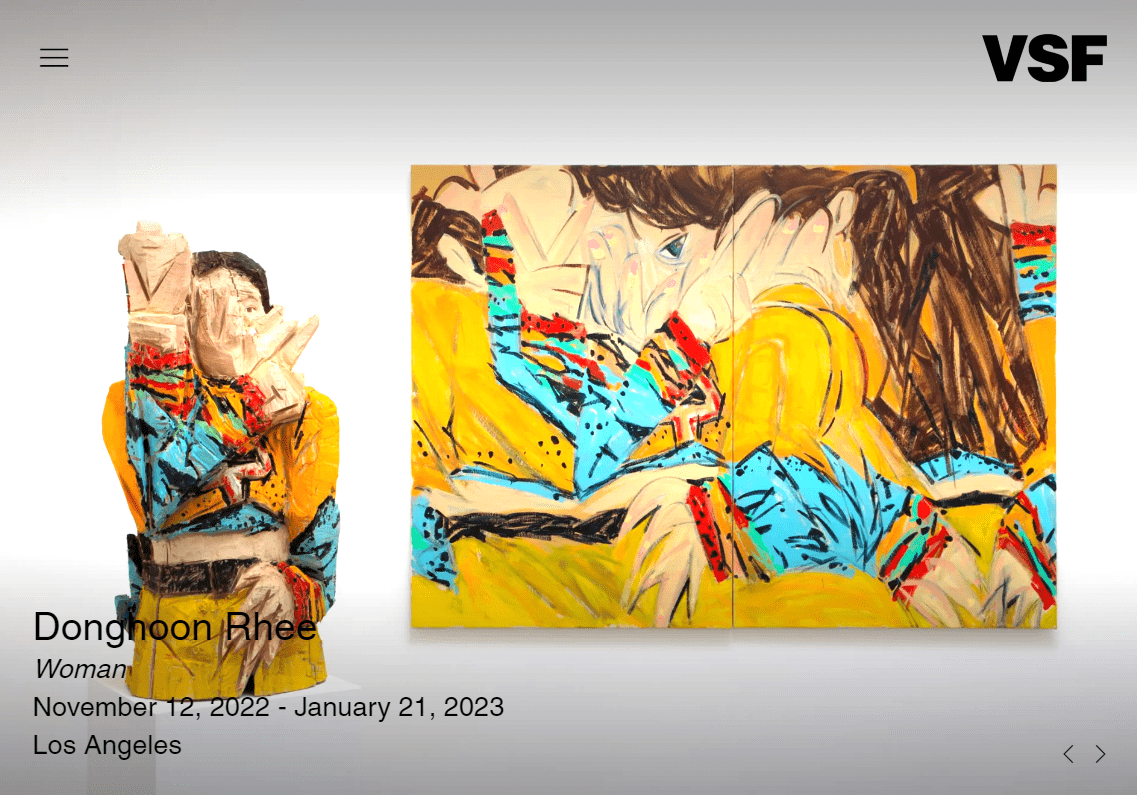

As much as any other object, the work of artists like Caro,

Matisse, and Calder demanded sustained observation. Their unique ways of

manipulating tributaries and lines were actually creating new spaces. Just as

there had been in the volume of a hairstyle, or the drape of a garment, or the

movement of a hand or foot, everything from the structure of a sculpture to the

composition and construction of a panel was full of possibility in terms of

reference.

Compilation 1 and Compilation 2,

which have been enlarged and inserted as a stand-alone feature removed from the

context of the individual works, form one axis of the exhibition. These works

were created on site rather than in the studio, as I wanted to utilize the

large walls and low ceiling heights of the exhibition space. Parts ended up

enlarged and the choreographed hands and feet have been separated. As is the

case with sculpture and relief, a system of order that reveals itself within the

process of creation can guide certain decisions. The figure of the subject on

stage became a sculpture, and the sculpture, in turn, became a relief of that

trajectory. The reliefs were then fixed to the wall, expanded, their pins

temporarily dismantled, and parts of the wall were repainted and placed in

three-dimensional space.