《Inhale, Exhale and STAY》(Toy Republic,

August 7–26, 2015) was created after she quit McDonald’s. In this exhibition,

Shin Min presented figures lying beneath ice cream, headless forms, slumped

bodies seated on toilet bowls in workplace restrooms, and dazed figures

standing behind cash registers—eyes hollow and tinged with restrained rage.

Here, she confronted a reality that remained unchanged despite her departure

from McDonald’s. There were always more workers ready to replace her, and she,

too, had to take on new forms of labor to survive. Under neoliberalism, the

service worker is always destined to lose.⁶ Through this experience, Shin

Min realized that her anger could not be directed solely at McDonald’s. She

came to understand that her rage stemmed from a tangled web of structural

injustices—not just from a single job site.

Following this period, the artist began to look back on the

histories and testimonies of marginalized voices within her own

communities—voices that have been suppressed under neoliberal society. Through

this reflection, she slowly traced the origins of her own anger and sought out

ways to give that anger form. One such point of inquiry was the human rights of

women who were exploited under the name of “sex labor” during wartime—a form of

inhumane violence enacted upon women precisely because they were women.

Expressing her rage at this brutal sexual violence, she staged a performance

titled 〈Basketball Standards〉(2016).

In this work, ten performers, their gender deliberately rendered ambiguous,

inserted their necks into basketball backboards and moved across the space. The

artist focused on the bodily gestures and the linear narrative structure of the

performance.

As her collaborator Kim Joohyun noted, Shin Min recognized that

performance is particularly suited for generating “discourses of difference

among individuals positioned differently.”⁷ In this piece, she choreographed

a process in which bodies slowly break away from imposed forms and are

dismantled and reconstituted into other bodily configurations. Unlike

sculpture, performance revealed the infinite potential of elastic temporality shaped

by the use of space. Having once sculpted bodily forms out of paper, Shin Min

gradually shifted to using her own body as material. In works like 〈New Labor Series—VOW Radio〉(2021), a pirate

radio broadcast conducted via Instagram Live, and 〈Invisible

Semi〉(2022), she actively participated as a performer.

In her writing on social media—another form of her artistic output—she reveals

her unfiltered self.⁸

This transition reflects how she has continued to subvert the

spatial logic of sculpture, which she first embraced, allowing her powerful,

large-framed, sharp-eyed figures to infiltrate anywhere, much like a

pamphlet-maker would disseminate their message.⁹ To me, this shift reads as an

extension of her sculptural practice—a move toward “the body” as a

temporal medium unbound by physical space, allowing for flexibility and

transformation. It feels like an unequivocally positive gesture: a declaration

of the artist’s commitment to solidarity with the world around her. Despite the

weight of the mid- to late-2010s—a period marked by the Sewol ferry disaster

and the rise of the MeToo movement, events that left her with an enduring sense

of helplessness—Shin Min’s work continues to channel those unresolved emotions

into forms of expression and action.

Making Art with Anger as Fuel

This memory remains a lingering question for the artist—a time

unresolved—and continues to act as a driving force that compels her to ask

questions and speak out loud. Yet, as the anger that motivates her artistic

practice becomes increasingly clarified, one wonders if it also brings her

closer to losing the very meaning of making art. For the more closely an

artwork touches reality, the less room there is for beauty. Feminist scholar

Jung Hee-jin writes, “There is always a distance between writing and the writer.

That distance is not tender. The closer it gets, the more antagonistic it

becomes. Avoidance, resistance, identification… In order for a person to write

about her own reality, she must first cut through an endless entanglement of

kudzu vines. One can see the experiences of others, but not even believe her

own.”¹⁰

In other words, the more deeply rooted one's positionality is in a lived

experience, the more impossible the work becomes—because summoning memories that

even the artist herself cannot fully recall requires both relentless

self-censorship and crossing emotional abysses.

Even so, Shin Min resolutely states, “Rather than indulging in

imaginative fantasy, I’ve always told stories that are closer to reality.” She

refuses to abstract or erase the anger of herself and her community, choosing

instead to foreground the inherent condition of realism in art.¹¹ In the field

of art, realism is often defined as “a representation that allows viewers to

recognize what is being depicted,” though it is “not necessarily aimed at

replicating what is seen.”¹² In Shin’s realism, the desire to portray the

present moment is inevitably imbued with her own subjective perception. That is

why she says, “I hope that anyone who sees my work will laugh, talk, relate to

it, and feel energized.”¹³ To this end, she not only learned how to see the

world through her own eyes, but also continuously contemplated how to allow

others to see the world through the eyes of the forms she creates.

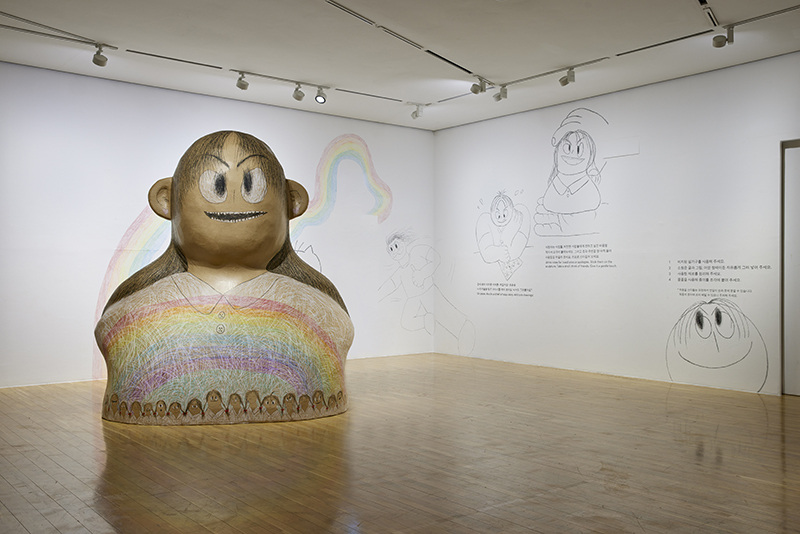

She now knows that large, bold figures stationed inside gallery

spaces are no longer sufficient to infiltrate the world. Because even the most

“open” exhibitions are, in truth, restricted by opening hours—and therefore

cannot represent “everyone.”

Shin Min knows this: art cannot change the world. And yet, she

continues to make art. Perhaps it is because she believes beauty can compel

ethics? Even if no clear answer can be given to that question, I recall the

moment when I found her work especially compelling—precisely when the question,

“What must an artist be wary of when engaging in social and ethical practice

beyond self-representation?” refused to leave my mind. More accurately, it was

the memory of the figure seen from behind in Shin Min’s 〈Our Prayer – I do not hate my fellow being / I love / I embrace / I

stand in solidarity〉(2022), and the melody of 〈Invisible Semi〉 that resurfaced.

A large-bodied female torso, donning an outdated hairnet—an

unfashionable style now rare, yet still worn for “hygiene reasons” or because

of “conventional aesthetic standards.” Her clenched lips and determined gaze

conveyed something more than mischief—there was resolve. A body, yes—but

ultimately, a face composed entirely of the eyes. And a dance: repeated service

gestures choreographed to a song, gestures dictated by the service industry.

Throughout the work, even though it remained unclear whom the laborer of this

era should resist, the moment was vivid: imagining workers breaking the chain

of competition and exploitation, rising up and reaching out to grasp one

another’s hands.

The moment of resonance came from that fleeting but aching energy

evoked by struggle and solidarity. And this energy alone is reason enough to

keep engaging with her work. That sufficiency, in whatever form it takes, will

undoubtedly reach her—and become another force that sustains her in continuing

to make and share her work.

About IMA Critics

“IMA Critics” is a visual culture research initiative organized by

the Ilmin Museum of Art. The project invites critics, writers, and editorial

professionals to revisit foundational theories of criticism, gain hands-on

experience with discourse production processes, and ultimately generate

meaningful outcomes in the field of art writing. In 2023, six researchers—Kim

Hae-soo, Park Hyun, Yoon Taegyun, Lee Heejun, Lim Hyunyoung, and Choi

Jaeyoon—participated in the program.

Park Hyun

Park Hyun is interested in the transformative moments that occur

when individual narratives intersect with contemporary society through art, and

explores these transitions through writing and curatorial work. She studied Art

Studies at Hongik University and earned her MA in Aesthetics with a thesis on

the ecological aesthetic potential of Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory. She

is currently working as a curator at the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Korea.

1. Park Hyun, email to Shin

Min, September 19, 2023.

2. I asked Shin Min what

she has been most cautious about throughout her self-representational practice

from the early stages to the present. In response, she explained her reasoning

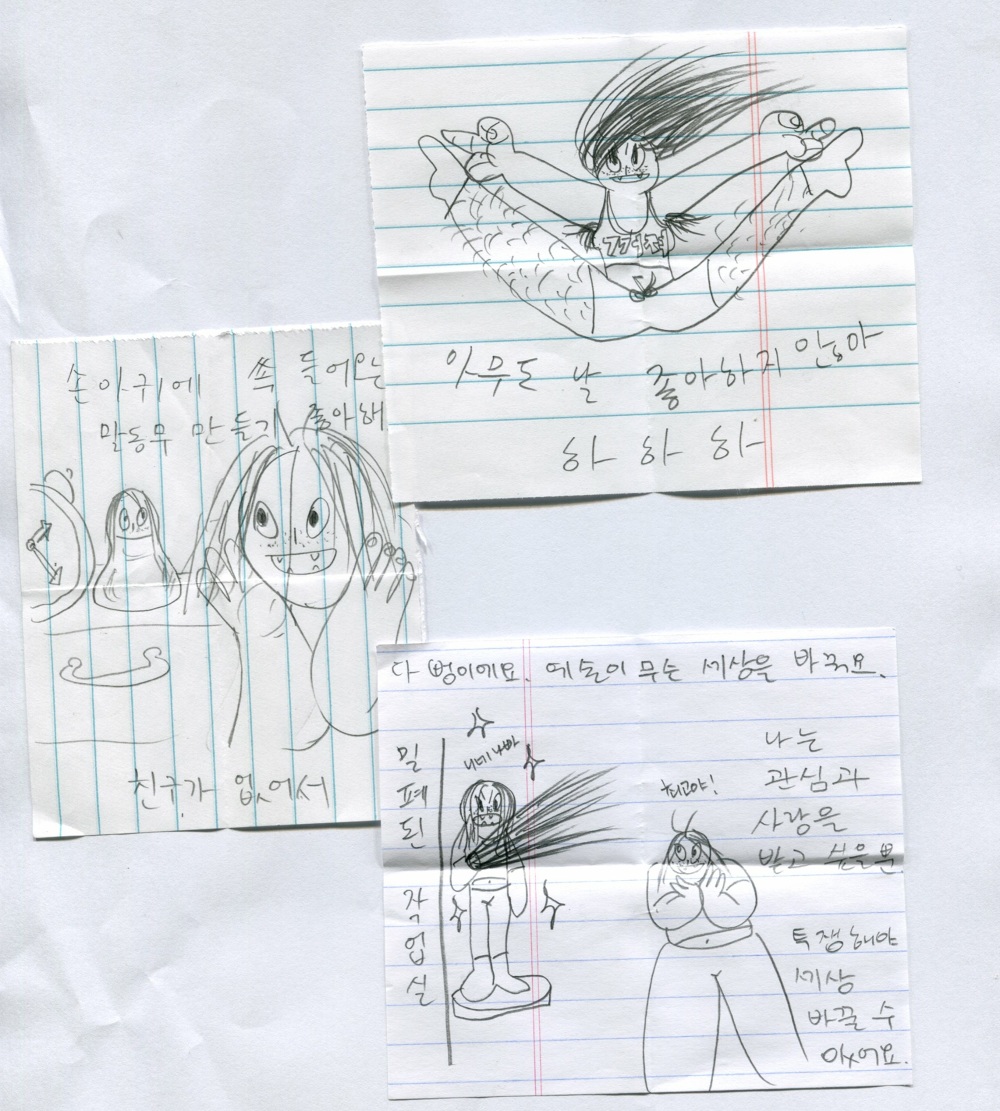

for incorporating “letter writing” into her work as follows: “A letter has a

destination—it is a place for the thoughts written on paper, a destination for

the heart. If that destination is myself, the letter cannot arrive. A letter

must be addressed to someone else. Putting the thoughts and images I selfishly

want to keep to myself into an envelope and sending them off without regret to

someone else—that act of letting my feelings flow outward like a letter is

something I strive to apply to my work.” Ibid.

3. Exhibition preface to

Daughters with Strawberry Noses (Place MAK, Oct. 18–30, 2011). 2011. URL: https://neolook.com/archives/20111018h.

4. “Let me be honest. For

this exhibition and future works, I had made up my mind to produce neat

canvases or solidly built sculptural pieces made from durable

materials—artworks that would be perfect for home decor and would entice people

to keep buying more. I needed to make money! So I bought oil paints and white

canvases. But every time I picked up a pencil and tried to draw in front of

those materials, I ended up producing images that were no better than a tiny,

embarrassing turd.” Ibid.

5. See Eiji Otsuka, The

Society of Emotionalization, trans. Shin Jung-woo (Seoul: Resiol, 2020), 47.

6. Referring to service

workers as “losers” here is intentional and contextual. According to Otsuka’s

argument, neoliberalism is fundamentally grounded in social Darwinism, which

carries an implicit agreement that the socially vulnerable are “losers” in a

survival competition. When the logic of individual responsibility is turned

toward the vulnerable, they are inevitably framed as failures. I agree with

this premise and therefore deliberately use the term “loser” to describe

service workers in this text. See ibid., 123.

7. Kim Joohyun, “The War

That Never Ends, There Are No Backboards: Shin Min – Basketball Standard,”

2016. URL: https://cargocollective.com/daughternose/2016-2.

8. Invisible Semi (2022)

was a performance presented in conjunction with Shin Min’s solo exhibition Semi

at The Great Collection (Sept. 3–Oct. 15, 2022).

9. Park Hyun, email to Shin

Min, September 19, 2023.

10. Jung Hee-jin, I Write

So As Not to Be Defeated by Bad People (Seoul: Gyo-yang-in, 2020), 116.

11. Seoul Museum of Art, “Seoul Museum of Art | Nanji Open Source

Studio Talk Program 5. Shin Min,” April 22, 2021. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N6Tgr2Vo6Jo.

12. Kim Jaewon, “Realism in

Art.” Korean Modern and Contemporary Art History Review, no. 22 (2011): 72.

13. Park Hyun, email to

Shin Min, September 19, 2023.