With

her video project Nonsense Factory, Yang Ah Ham has been selected as the

final four candidates of 2013 Korea Artist Prize. Today, it is obvious that

Ham’s work is worthwhile for us to probe into the conceptual creation of image.

Ham’s images could neither be regarded as the technical pursuit aiming at the

abstract category of aesthetic, nor be taken for the media for any public

issues; it even could not be looked upon as the representation of the artist’s

self. In other words, this very image is no longer an image belonging to

someone or something, but the image of neighboring. How to think through the

relation of the image as neighborhood, or the image neighboring on? How does

the image neighbor on? In this regard, it seems that Ham proposes a basic

strategy similar to that of Deleuze’s. The latter reveals the indistinguishable

between the real and the virtual. The artist, on the one hand, attempts to

present, in the everyday life, the indistinguishable between the phantasm and

the routine. On the other, the artist also activates the dynamic relation (the

be-coming) in order to repeal the privilege proper to the monopolization, by

which the artist mobilizes the experimental concepts passing through the

relation between self and images, image and image, and the others and the

images. According to this, maybe, only Harun Farocki’s concept of image could

respond to that of Ham Yang Ah’s.

We

could consider Nonsense Factory of 2013 as extension of her

concept Adjective Life 〉 Nonsense Factory of 2010. This idea Adjective

Life 〉 Nonsense Factory and Harun

Farocki’s soft montage both attempt to stop reifying the image in service of

commodifying and empowering contemporary art in the name of the original.

Contrarily, they observe the clichés of the world at present, or those produced

or used by this world to describe our day-to-day life, by which they try to

present the paradox of the society of the spectacle from every different

aspects: the precarious life (of multitude), and the inhuman images (by

commodification, the machine, and the spectacle.) This way of re-touching the

image is the conceptual strategy that Farocki called the soft montage, and also

the one that Ham uses to think of our life. In fact, they both go further than

the conceptual strategies of relational aesthetics or that of post-production

in order to make the relation in every work more clear and, at the same time,

depart form the position of artist, as a centralized subject, to the constantly

changing state of the relation. Therefore, it could be said that while pointing

out the production of the image, they are proceeding with an artistic act of

the political and the critical (in other words, the art itself should become an

adjective.)

Though

Farocki’s and Ham’s artistic acts have their differences, they are not

different in the strategies of artistic presentation and concepts but in the

positions on aesthetics-politics. It is just like what Kang Su-mi has pointed

out that Yang Ah Ham uses the inequality in the Korean title of the exhibition

held at ArtSonje Center, Adjective Life 〉 Nonsense Factory, by which the inequality is designated as the

possibility of art as such. Yet, in sense of mathematics and psychoanalysis,

the inequality respectively suggests the proximity in the former and the drive

in the latter, in which Lacan further infers the schizophrenic force of the

phantasm. The world of capitalism is as unfortunate as what Guy Debord, in tune

of over-saturating ideologies, has proclaim that the real world has been

replaced by a reified world of commodification. It seems that this proclamation

might be what Ham’s Adjective Life has been designated for.

Nevertheless, it is due to Adjective as a precarious relation

that the possibilities of “〉” (greater than) appear.

Yet,

it is because that Lacan’s or Farocki’s ways of dealing with the relation of

objet a and A(S) (big Other) follow the double inequality of the formula of

phantasm, “$ ◊ a”, and aim at thinking of how object a being produced from A(S),

Farocki, thus, dangles after this very European critical thinking, in which he

often implicates some kind of big Other as the controller in his works.

Although Yang Ah Ham keeps this relation, she arguably propels another

supposition; that is to say, in a capitalistic society of the radical

democracy, the objet a is the experience of the excess of the big Other, of

which this experience coincides the phantasm with the routine. In this regard,

unlike Farocki, whom often deploys the work in a confrontational gesture, in

her collection of video images of television, Ham goes deep into the

observation and the apprehension of experiences, and touches the moment of the

craftsman that the images have revealed.

Therefore,

in this exhibition, Ham has tried to invite a craftsman of painting restoration

to do a live performance. Apparently, this deployment can enhance the

interactivity of this project in order to make its audiences to more clearly

grasp a possibility; that is to say, even as a part of the mechanical

production, one could still engender creativity (the plus creativities). Thus,

this artist, who is also located in the state of the adjective (just like her

project in 2007, Adjective life – Out of frame) can produce a

visible mise-en-abime in the world of images, by which it brings the

audiences of everyday labour back to the world of self, and makes them see

the plus creativities outside of the big Other as the society of the

spectacle.

This

is the possibility similar to what Richard Sennett has inferred to. Sennett has

spent nearly 20 years in field work to figure out this possibility. In

accordance with his mentor, Hannah Arendt’s argument for

the work differing from the labour, Sennett’s inference takes

one step to depart from the phantasm of Grand Narrative in order to more

carefully think of the possibility of emancipation and the value of humanity.

Nevertheless, these two theorists both avoid the problematics of the artists.

(Interestingly, Ham, on the other hand, questions the given identity of an

artist.) Maybe, after several times of economic crisis and after Asia having

become the new platform of globalization, Ham attempts to change the given

channels of distribution of the sensible from the aspect of field work

observation. This attempt is very important. The visibility

of mise-en-abime that she has revealed can make differenciation

between the everyday labour and the plus creativities. Here, it appears a

new concept; that is to say, the given distribution of the sensible is

neighboring on the virtual one. In contrast with Jacques Ranciere’s vague

conception of emancipation in the theory of distribution of the sensible, Ham

proposes an even clearer method of experience.

After

the globalization, the common phenomena seems to be that every place in the

world is full of factories, science parks, and shopping malls; furthermore,

almost everyone tries to survive under the situation of overwork. If the

hierarchy of military management in 19th century has became the constitutional

structure of society, Asia after 2000, followed this very same structure of

globalization that the Western countries had been planning for decades: every

connection of the social relations, especially that of relations of production,

has been taking private. This phenomenon has been carrying forward to our

relations of production and working situation. On the one hand, we as the

individuals more and more have to deal with the situation that the production

could only make sense to some minorities as investors, but it remains

non-sensical to the most majority that are involved in mass mechanical

production. On the other hand, the distribution of the sensible highly related

to the distribution of the global work- force clearly ask us to deal with

the differentiation of structure and relations of production, but not

with the new sensibilities that could always been bought over anytime.

A

partition board is hung at the entrance of the exhibition; thus, the entrance

is scaled down as a limited doorframe. When entering the dark room of

exhibition, audiences will step onto a slightly swaying stage due to one’s

weight. On the stage, there is a steady working bench.

The mise-en-scene of this stage is some sort of declaration of

the situation; that is to say, Fifth Room: Factory Basement: we are

situated on a ever swaying surface, yet assigned to a fixed working position.

In front of the stage, there is the biggest video projection of this

exhibition, where is the first one of the six rooms (six different places of

production): First Room: Central Image Box Control Room.

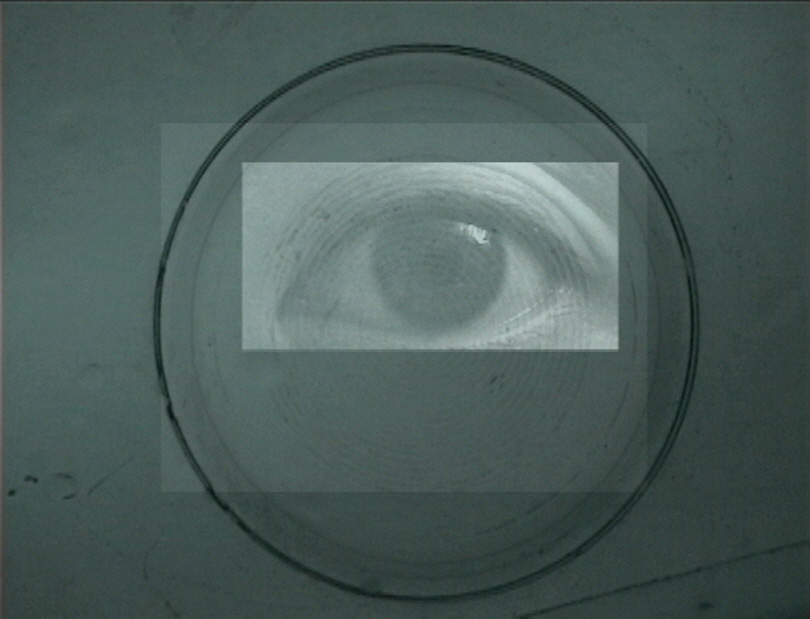

Throughout the

whole exhibition, there is an emblematic image appearing in many works. That is

a black and white inverted image of Little Angels Folk Ballet of

Unification Church. Actually, this inverted image was a mistake that had

happened in 1972 during the television broadcasting. Thus, it seems that this

contingent contradiction could be regarded as the process that Korea has

undergone from the conformity to the ideology to the hidden real of the false

ideology. When the inverted image with limited dpi is enlarged to the extent

scale, that one cannot identify the figure of Angels in image but only the

pixels, one can see that there are many different working stories embedded into

the pixels. Thus, just like the inverted image, every working story intensely

presents the paradox co-existence: the routine and the expert, the labour and

the knowledge, the system and the invention. These stories reveal that people

resist the reality of this contradiction and, at the same time, subjugate to

it. Though these video clips could be seen in many documentary reports,

in Central Image Box Control Room, they, on the wall of projection,

intensely focus on the moment at the epiphany moments of the expert knowledge

and the distinctive operation. Undoubtedly, through Ham, it becomes visible for

us the moment at the borderline between the labour and the creation.

Due

to the space installation of constellation without any certain guidelines, the

swaying state of ambiguity and uncertainty that the audiences have felt in the

first installation would make the full-dimensional exhibition space become the

space of wandering phantoms. Since what audiences have seen are those media

images familiar to them, these images, thus, seems to them that they are

looking at various cadaver-images in the capitalistic society of the

reification, the commoditization and the fantasization. Yet, the audiences

in real, who are wandering in these rooms of factory, are like the phantoms

that just lift away from their cadavers and search for the moment of encounter

that might be deployed by artist (in sense of Derrida’s concept of specter). Nevertheless,

this very encounter is not that with artist, the creativity or the masterpieces

of art but that with dehors (outside in) being inherent in the labour

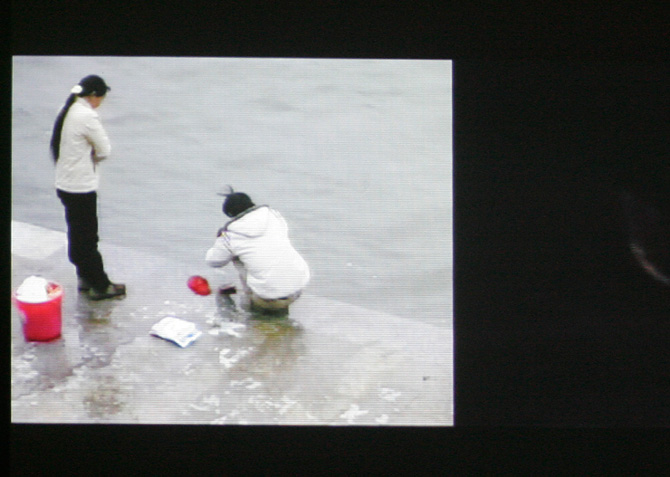

of one’s self. On the left side of stage, we can see a video installation named Perpetual

Euphoria: there, the three videos respectively are: the one is the image of the

cluster of bees killing each other; the other is that of a long take shot on

merely one street block; the third one is the electronic board which existed

already on the rooftop of one building in the first image of street scene (at

the right top corner.) It showed commercial or news films. On this electronic

board, artist adds more news clips or clip made by her and puts them back in

the screen of the electronic board. Ham finished this work during the period of

Seoul Mayor Campaign. Therefore, that what artist uses this particular kind of

installation to make us recognize is not the difference between nature and

alienation, but the co-incidence of three different kinds of living time and

surviving desires. Through the window on this partition parapet, we can see the

brief project discourse of Nonsense Factory. Ham appropriates the given

images that audiences can immediately be immersed in them, but still, in every

instance, sets up the distance that alienates her audiences from the simple

projection of one’s self on the images; inasmuch as, artist makes us

spectralized.

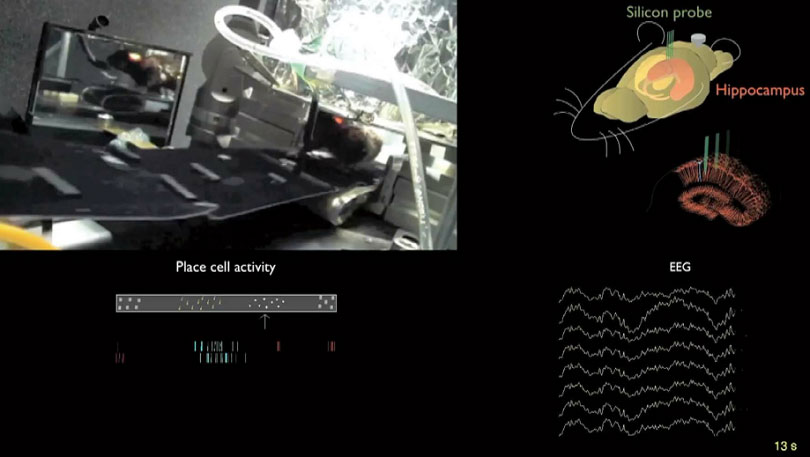

On

the both backsides of Central Image Box Control Room, there are two

triangle cubes. On the one side, it is Sixth Room: Blue Print Room for

Future Factory; on the other, is Bird’s Eye View (2008). The former

work is a camera shot set on a mouse’s head. At the same time, the work uses

various kinds of instruments to observe and diagnose this mouse placed in the

constant movement within the water supplying system. The artist presents this

work in a way of respectively and simultaneously displaying following three

aspects – the drawing of the assemblage, the CCTV monitor image, and the

diagnosis data of the mouse. The later work is the video shooting of pigeons at

the old Seoul station built in Japanese colonial period. There are three

videos. The first one is the pigeons in a confined space shot by high-speed

camera. The second one is a CCTV camera pilot set on the back of a pigeon

recording the vision of this pigeon. We should note that in the second video

image the previous confined space has been opened up by a window. Thus, the

third video image seems like the vision of one pigeon flying, regarding other

pigeon fly toward the city this time. These images tend to create certain kind

of illusion of the in-human images.

Behind

the wall of Central Image Box Control Room, there are two sarcastic and

ambiguous works made by Ham. One is the installation of neon-light tubes

named I came for Happiness/Submission, but at the end of English part of

writing with Romanized cursive style (「 I come for」 ) is blurredly written,

therefore the blurred Korean words in the title get a double meaning:

happiness/submission (haengbok/hangbok). The other is a statue made out of

chocolate entitled An Artist, one part of project Sustained Portraits,

expressing the paradoxical intention of artist. These two works respectively

are Second Room: Welfare Policy Making Room and Fourth Room:

Artists’ Room. Although these two works are apparently presented as works of

art, they respectively correspond to the stories of the lost of conversation

and that of discontent and Kitsch. These two stories are the negativities being

inherent in-between the ideology and the identity. Thus, on the other side of

the stage of Factory Basement, there is Third Room: Coupon Room,

which is the work most related to the labour and to the implication of desire.

We can see a lot of images dealing with finance bills, such as currencies or

credit cards. This work is also the installation that emphasizes the production

line and the uniform. Furthermore, as it should be in this work, in the

beginning and the end of Coupon Room, it inserts the images of the bubble

performance referring to artist, and the images of the red pen-ink referring

to Factory Basement. Behind the projection of the fountain pen with red

ink, there’re stairs for audiences to get to the top of the image. This

hierarchic disposition of ascension makes the audiences feeling themselves like

the owner with power to write down the history, and with the panoramic view of

the whole factory space.

In

fact, these six rooms with six themes correspond to six reports from each

section of the factory, intertwined from the given images of documentary

reports and the imagination of artist. These six successive reporting stories

are just like Kafkaesque journey, an absurd course full of fantasy. The only

difference is that, in Kafka’s journey, the surveyor or the public official,

who visits the castle, becomes the worker and the reporter of worker’s

newspaper in Ham’s version. In this regard, we should surely mention the most

profound artist of image, Orson Welles, in relation to Kafka. From Orson Welles

to Terry Gilliam or Steven Soderbergh, the core of their image narrative was

the reality full of gothic noire (darkness). Relatively, Ham pushes forward the

Kafkaesque absurdity of contradiction to the intertwined and stratified

experience of reality.

In the era of globalized creative industry, labour and

work cannot be distinguished by Arendt’s dichotomy of “survive/create.” In

fact, what the everyday life sustains is the constant crossing of

in-betweenness; that is to say, the precarious desire situates in-between the

comfort of everyday life and the symbolic achievement of history. Through the

unfolding from the in-human images (the animalized objectivity), the images of

others (the television documentaries of everyday life), and the images of

artist (the self-dissolution), this space deployment of constellation is bogged

down into the detailed laboring experience of every individual case. At the

same time, in the space of crossing and intertwining relation, it brings about

a rhizomatic world that is not to represent the reality but to change the

reality.

From

this time of re-configuration of Ham Yang Ah’s works, we can clearly focus on

her viewpoint on the experience and the world, and how her concept re-produces

the images. We, the audiences as phantoms, are just looking at ourselves living

in the capitalistic society and searching for the emancipatory moment of a

Deleuzian nomad: the rencontre (encounter) of cadaver and phantom.

1. Whether it refers to the saying of Hans Belting’s global art or

that of Boris Groys’ documenta, it shares the similar meaning.

2. 〈Adjective: A Subtle

Morpheme of Life, Non/Sense Script〉 in Ham Yang

Ah (coll.), ed. by SAMUSO, 2011, p.169.