From the Albatross to the Parrot

Birds did not appear in Bae Young-whan’s work for the first time in this

exhibition. In his 2008 solo show 《A Very Luxurious and Shabby Insomnia》, the

work Worry(2008) featured an owl made of broken bottle

shards, while November presented several birds

fashioned from bottle shards and wire. Some birds appeared only by name, such

as Albatross(2008). Thanks to its long wings—spanning

three to four meters—the albatross can soar for dozens of kilometers without

flapping, but these very wings cause trouble when taking off or landing, and on

the ground, they drag along in an awkward display. For this reason, Baudelaire

described the bird as “a prince in the skies, but wretched on the ground.”

Bae’s Albatross is

a pile of wood shavings enclosed in a square wooden cage. On the shavings are

imprecise-looking measurement marks. The wooden frame of the cage is also

inscribed with marks, and these straight, regular scales contrast sharply with

the crumpled, bent, irregular lines drawn on the shavings. Compared to the

neat, straight marks of the frame, the ones on the shavings are inaccurate,

haphazard, unstable—in a word, non-standard. The juxtaposition of straight

lines implying standardization and measurement against these unruly,

non-standard lines had also appeared in Ship of Fools(2007).

That work consisted of irregularly shaped pieces of plywood gathered between

wooden posts marked like depth gauges, with measurement lines also drawn on the

randomly cut wood scraps. About Ship of Fools, the

artist remarked: “The core element of this work was to draw arbitrary

measurements on discarded wood scraps and recombine them into sculptural form.

Of course, a ‘handmade ruler’ is not accurate. But that inaccuracy becomes a

question about the very grounds for standards of accuracy. It’s also a question

about what’s considered normal or abnormal.”

Up

to this point, Bae Young-whan’s work had focused on those “who do not register

in the precise social statistics on the unemployed or homeless” (Park

Chan-kyong)—external beings unable to be assimilated into the standards and

measurements demanded by society. People have labeled them “marginal lives,”

“subcultural styles,” “subaltern identities,” attempting to read in their

non-standardness a potential for dissent and resistance. Some have seen in them

“a sharp, biting symbol of social discord and personal resistance,” while

others have perceived “a desire to represent the universal subject who bears

society’s fundamental impossibility.” For critic Sim Sang-yong, the wood

shaving–albatross was “the poet’s innate attitude that rejects any kind of

coding.” “This fated bird has fallen to a jeering earth, transformed into its

loosely piled, disparate measures. At once Baudelaire and Bae Young-whan, it

mocks the archers—those who theorize and contextualize. There is no standard

that applies to all of us, no average to reference. There is no manual, and no

need to feel restless.” At least at this time, the artist himself seemed to

believe that such possibilities could be found in non-standardness itself. The

wood shaving–albatross, seemingly trapped within the frame of a cage, could

slip out precisely because of its amorphousness and irregularity. Albatross trusted

in the possibility of escape for the non-standard being—caught, yet not caught,

within the measure of the cage.

The Bird’s Song

Today’s situation, however, is vastly different. The “subcultural subjects” who

once strummed guitars and sang old pop songs are now envied as tenured

employees or public officials, nostalgically consuming the commodified remnants

of past non-standardness. Young people willing to undergo plastic surgery and

extreme dieting to become entertainment company trainees accept the inhuman

competition of audition programs as a rite of passage to enter the mainstream.

Startup founders who achieve economic success emerge as mentors to society, and

everyone strives to follow their model. Faced with the threat that “if you

don’t globalize, you’ll be left behind,” corporations, governments, public

institutions, and even cultural and art venues like museums proclaim global

standardization as their goal and compete to enter the world of standards. In

short, the realm of standards and measurement is now erasing any outside

entirely, dominating society.

The

installation Land of the Birds is a fable about

this far more powerful world of standards and measurement. In contrast to the

relatively thin wooden frame of Albatross, the cage’s

structure here has become a thick, metallic perch that would not yield under

any force or pressure. The faint, hand-drawn lines have turned into deeply

incised, precise measurements. Perched atop the golden rod is a gigantic

parrot, wearing a golden cap pulled down over its eyes. A cage is no longer

needed for this bird. Having so thoroughly internalized the scales of its

perch, it has no thought of escaping. Instead, it seems to passionately praise

the inevitability of measurement and the virtue of the standardized—proclaiming

that, whoever you are, in whatever field, you must master the standard scale.

Fail to conform, it warns, and you are nothing but social waste, leaving no

trace. In the face of the parrot’s repeated song of threat and praise, the

non-standardness of the wood shaving–albatross becomes a trivial, laughable

anachronism—an act of foolish, naïve bravado.

The

parrot gazes down upon globes. In the earlier work Impossible

Dialogue(2012), the globe sat at the rear end of a desk, as if

crouching—like a newborn it had birthed, or like excrement it had

excreted—leaving open the possibility of becoming either a new life or waste.

In The Bird’s Song, however, the globe is pierced

through the center by a thick metal axis and firmly clamped within a golden

frame engraved with heavy measurement lines. Strong standards and measurements

encircle it so completely that escape now seems nearly impossible. The globe

still has the jagged, uneven surface of an unshaped rock, but under the uniform

dimensions of the golden frame—like orthodontic braces—it seems destined to be

trained into a smooth, standardized sphere before long.

From

a hanging hand microphone (###), the song of the

parrots—whose numbers and volume are ever increasing—pours out. It is an

unintelligible murmur made by layering news from around the world. But it

hardly matters whether the words are understood. As Alain de Botton has noted,

“The news is the ideal and supremely serious excuse for not paying attention to

things more important than the news.” When we “feel anxious and want to escape

from ourselves without knowing what’s truly important or what we should do

right now,” we “immediately assume that the new must be important” and consume

the news. The parrot’s song, woven from such news, is ultimately nothing but a

placebo for soothing our own anxiety and unrest.

In The

Bird’s Song, there are still some globes that have not yet been

fitted with the axis-and-frame apparatus—still jagged and irregular in form. Is

the artist suggesting that some ‘hole’ for escape, some ‘outside’ to this world

of standards and measurement, still remains, somewhere?

Abstract Verb – Can you remember?

Ahn So-yeon has described Bae’s “Abstract Verb” as “an attempt to depart from

all materiality.” The abstract verb “abandons all the plastic efforts once

summed up as ‘shabbiness’ or ‘the touch of the hand,’ leaving only acts and

sounds scattered in the air. This can be seen as a shift to an abstract world

distanced from the realism once pursued through material and labor, and as a

choice of an inner world of silence over the rich narratives meant to achieve

active communication.” Kataoka Mami reads in “Abstract Verb” an Eastern

aesthetic that “discovers the invisible presence of the peripheral in contrast

to the center, or the air or forces surrounding the visible object rather than

the object itself.” She says the artist’s work aims for “a reform of

consciousness that re-discovers and re-illuminates the vast space linking

self-reflection to the universe (the world).”

It

is clear that some kind of shift has taken place in Bae’s work, but to

spiritualize or interiorize it with phrases like “from material to spirit” (Ahn

So-yeon) or “sublimation from silence to the sublime” (Kataoka Mami) seems to

me premature. Even if we interpret this shift “not as a break from the past

spheres of concern in the face of reality, but as an attempt to expand into the

hidden domains of the inner and the spiritual in order to achieve a dialectical

unity,” there must at least be some catalyst to mediate between the ‘past

spheres of concern’ and the ‘expansion into the inner and spiritual.’ I believe

“Abstract Verb” is precisely such a work that presents this turning point.

Bae’s “Abstract Verb” is not merely a style of expression, but a message in

itself, revealing the artist’s consciousness of movements and actions, and of

the subjects of our time.

The

first “Abstract Verb” piece, Abstract Verb – Dance for Ghost

Dance(2012), was created by filming the scene of holding and dancing

with white dress shirts, then erasing the dancers from the footage. The result

leaves only two white shirts moving like ghosts. These white shirts recall the

white-collar crowds that once filled city streets during the democratization

protests of 1987. For all the well-known reasons already recounted ad nauseam,

many of those subjects now live entirely different lives. To speak of them

today would require words like “betrayal,” “institutionalization,” or

“compromise.” In the video, Bae erases these subjects, leaving only their

movements. By removing the subjects from the acts and motions—focusing not on

the “who” but on the “what” of action and movement—the gesture of the “abstract

verb” is complex. On one hand, it works from disillusionment and distrust

toward the subjects of movements and actions. In this respect, Bae seems to

place no further expectations on such subjects—whether they be “subalterns

opposing the aesthetic principles of dominant culture” (Baek Ji-sook) or “the

working class as a universal subject” (Seog Dongjin). On the other hand,

however, this disillusionment and distrust is tempered by a desire not to

discard the acts and movements themselves, but to remember and re-summon

them—hoping they might be recalled and revived by other, changed subjects. To

achieve this, the acts and movements must be freed from their former subjects.

This

attempt to liberate acts and movements from past subjects can also be found in

Bae’s more recent “letter” works. The Garden of Disappearing

Letters(2014), installed for the Anyang Public Art Project, and Temple

of Light(2015), installed in front of the former Workers’ Party

Headquarters in Cheorwon, feature structures surrounded by disappearing

letters. These “disappearing letters” are characters that can no longer be

read. Unable to be read, they remain only as visible objects, without being

voiced. Voice arises from a concrete subject articulating something. A letter

stripped of voice is a letter from which the speaking subject has been erased.

Such textualized speech erases the individuality of speech—tone, timbre—and

universalizes the potential of words. Now these letters could be realized in

entirely new speech, by anyone. In this respect, textualization works in tandem

with the “abstract verb”: just as textualization removes the voice and sound of

speech to detach it from the subject, the “abstract verb” liberates acts and

movements from their subjects. The challenge now is to find and seek anew how

to give voice to these letters, how to re-summon those acts and movements.

The

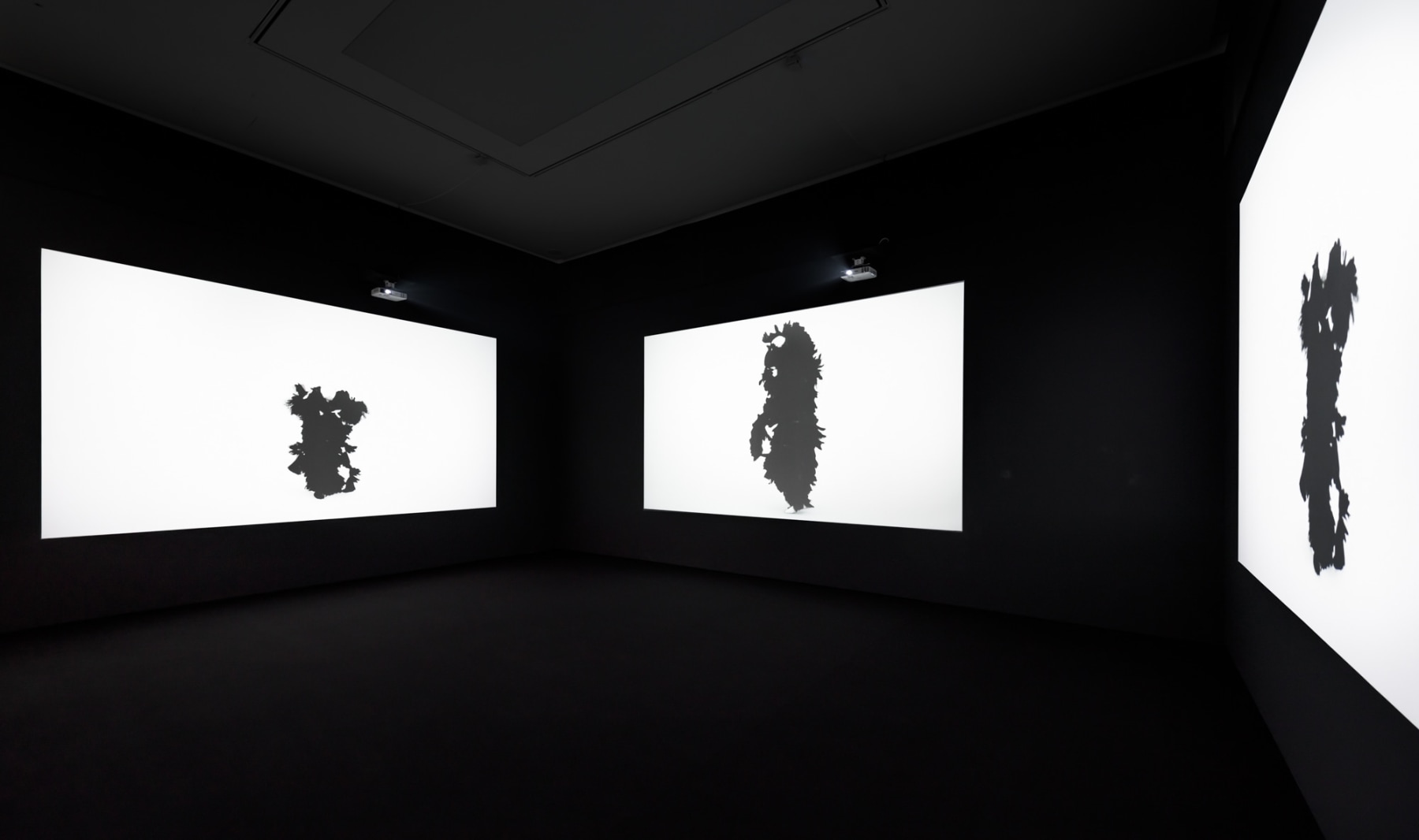

new video work Abstract Verb – Can you remember? takes

as its central theme the recall and memory of movement and action. In the

video, movements of dancers clad in feathers of different colors are visible.

With their bodies erased, what we actually see are the motions of black

feathers, orange feathers, and feathers blending both colors. They move alone

to the rhythm, sometimes facing each other, sometimes appearing together on

screen to dance. To create this work, the artist met with several dancers,

rehearsed countless times, filmed many scenes over and over. He sought

movements free from the established forms of any existing dance. What he wanted

was free dance, unrestrained by convention—movement entirely at liberty. But

escaping from familiar, conventional forms is never easy. To embody movements freed

from the established forms of dance, a dancer must cast off their habitual self

and draw forth new motions from their own body.

This

effort is a key to understanding Abstract Verb – Can you

remember?. From the production process onward, the artist was calling

forth a different subject, a changed self. The new subject of action and

movement does not arrive from some external place; it can only be summoned

through the action and movement themselves, within them alone. This is clearly

revealed in the relationship between the black-feathered bird and the

orange-feathered bird in the video. In one scene suggesting their dynamic, the

black-feathered bird and the orange-feathered bird move somewhat similarly, yet

with slight differences. The orange bird glances at the free movements of the

black bird, struggling to imitate them—unable to grasp its own rhythm or move

freely in its own right, floundering to mimic the black bird’s motions.

While

this floundering remains mere imitation, the orange-feathered bird comes to

resemble the parrot in The Bird’s Song—straining to

adapt to the rapidly dominating standards and measurements of the world,

soothing its own anxiety and unease with the parrot’s song. Yet Abstract

Verb – Can you remember? suggests that it is precisely in this

floundering and writhing—only in this—that a memory of some rhythm, sleeping

for ten thousand years (Ten Thousand Years of Sleep, 2010),

might be recalled alongside a new subject.

1.

Interview, Bae Young-whan 97–08, p. 132.

2.

Charles Esche, “Rebel Without a Cause/Loser With a Cause,” Bae Young-whan

97–08, p. 63.

3.

Seog Dongjin, “A Sensible Life, A Sensible Artist,” Bae Young-whan 97–08,

pp. 63, 92.

4.

Sim Sang-yong, “Subtle Revolt or Prescription for Existence: Reading Bae

Young-whan’s World, from Popular Song to Insomnia,” Bae

Young-whan 97–08, p. 54.

5.

Alain de Botton, The News: A User’s Manual, p. 286.

6.

Alain de Botton, The News: A User’s Manual, p. 286.

7.

Ahn So-yeon, “From Material to Spirit: The Many Ways of Singing Aerin’s Popular

Song,” Popular Song – For Elise, p. 12.

8.

Ahn So-yeon, ibid., p. 12.

9.

Kataoka Mami, “Unspeakable Landscape of the Mind: Sublimation from Silence to

the Sublime,” Popular Song – For Elise, p. 89.

10.

Kataoka Mami, ibid., p. 92.

11.

Ahn So-yeon, “From Material to Spirit: The Many Ways of Singing Aerin’s Popular

Song,” Popular Song – For Elise, p. 12.