Annotating

history

This

exhibition unusually seems to invert the hierarchy of main text and annotation.

The fragments of information that constitute the work—the supposed object of

presentation—appear in higher proportion than the work itself. Room 3 of 《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o ia e ia》 is no exception. Here

Kim revisits his Summer Days of Keijō—A

Record of 1937 (2007) and newly configures it as an expanded

installation spanning the entire exhibition hall.

The diverse records, images,

film scenes, and timelines added in this process function as annotations that

supplement and explain; they closely read together with (Korean) history and

the history of the artist’s works. Kim especially excerpts

and questions, along the axes of generation, extinction, and change, how things

are recorded and lost, by bringing in the records of Gwanghwamun that have

unavoidably undergone repeated alterations in history; images of Sungnyemun

that burned in 2008; his own video works related to fire; and the burning

scenes in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice (1986) and

Akira Kurosawa’s Ran (1985).

Distinctively,

Room 3 expands thought on the ownership and circulation of surviving records

through cinematic language. For example, both Sacrifice and Ran involved

sets burned by their directors; yet, having been created as films, they reveal

the duality of the medium by being recorded permanently. Meanwhile, at the

center of the hall, two films made as part of A Record of

Drifting Across the Sea—also viewable on the artist’s website—are

screened at set times, indirectly addressing accessibility and circulation of

the works. The video Actualina’s Makgeolli Making (2020),

in which the fictional YouTuber Actualina (who also appears in the screening

work Head Is the Part of the Head [2021]) teaches

how to brew traditional liquor, summons the YouTube format while interrogating

the belief system that there exists an original essence of tradition.

As if to

prompt “a re-evaluation of the concept of ‘boundary,’ which, despite being

necessarily fluid, repeats petrification, and of knowledge that settles in that

misunderstood concept,”³ the artist experiments with the limits of cinema and

intersects his gaze with the present of history. What of the architectural

staging elements that constitute the exhibition space? They are unfolded as if

folding the frame of history and drawing a new terrain with that transformed

frame. As we roam or sit across the museum’s wood floor, irregular-patterned

textile carpet, and plywood plinths, our bodies naturally become subjects

traversing the boundaries produced by the collision of differing materials and

surfaces.

Bracketing

a place

Bracketed

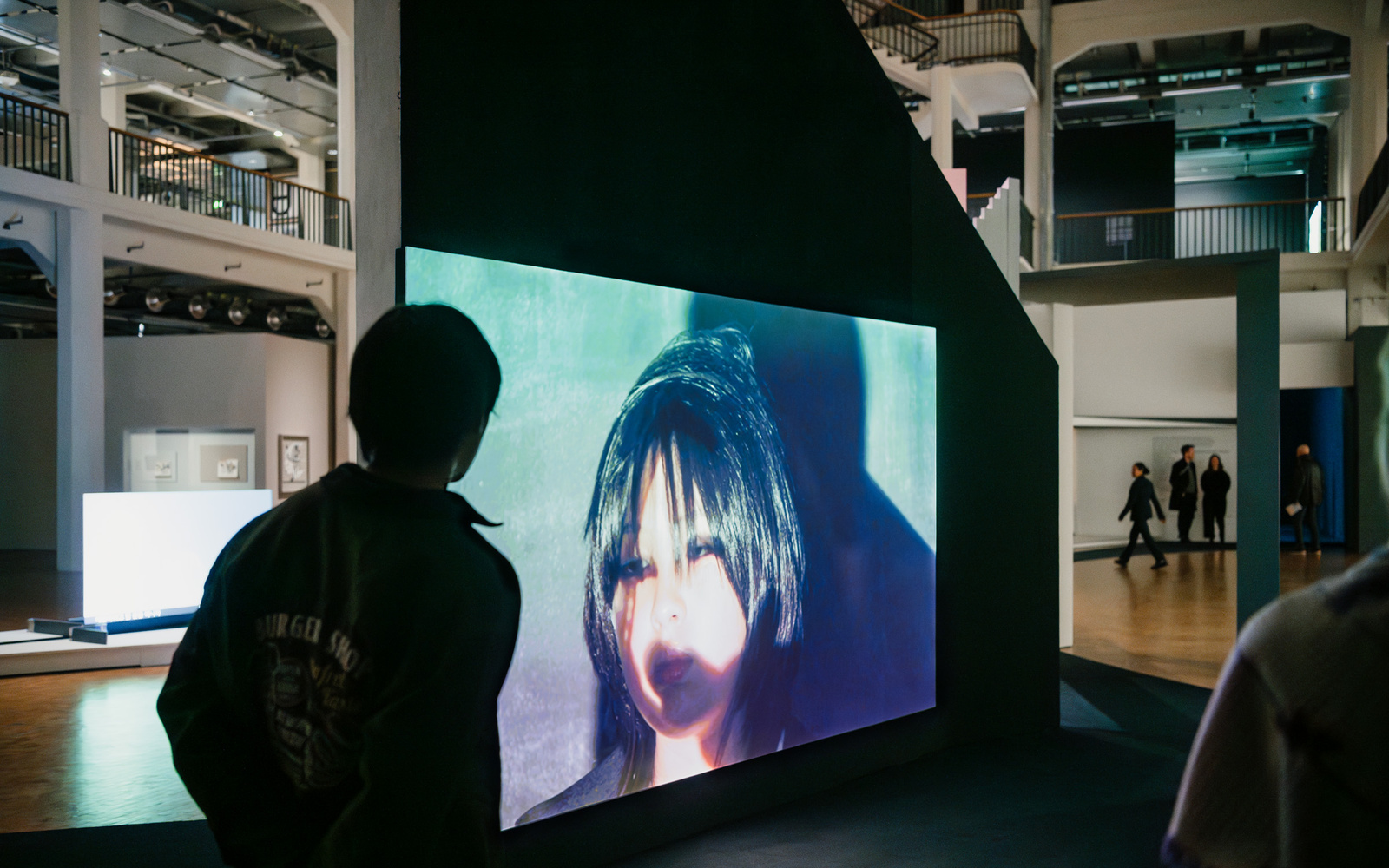

between the two rooms that “begin” and “end” the exhibition, Room 2 most

clearly manifests the artist’s thought and gaze toward fluid objects. As a

space that adds new rhythm and layers to text, the bracketed space is sometimes

ambiguous, provisional, and communal; reflecting this, the exhibition presents

the third video installation of A Record of Drifting Across the

Sea, Untitled, in an unfinished state. The

most prominent elements here are, without doubt, the architectural language and

experimental exhibition grammar. Platforms of different heights and slopes;

columns, corridors, and stairs whose functional roles seem delayed; reconfigure

the rectangular room.

The spectator’s body reacts and adapts to these

structures, drawing their own viewing path. Amid a space filled with various

images and sounds, writing and speech, movements and light, documentary

photographs and images created by the artist maintain only loose connections.

Stage lighting installed at the center of the ceiling, casting toward a

pyramidal skylight, and a curtain dropped in the 2nd-floor exhibition hall

through an opening in the floor’s center, make it appear as though the two

spaces are connected vertically like the up-down or front-back of a stage.

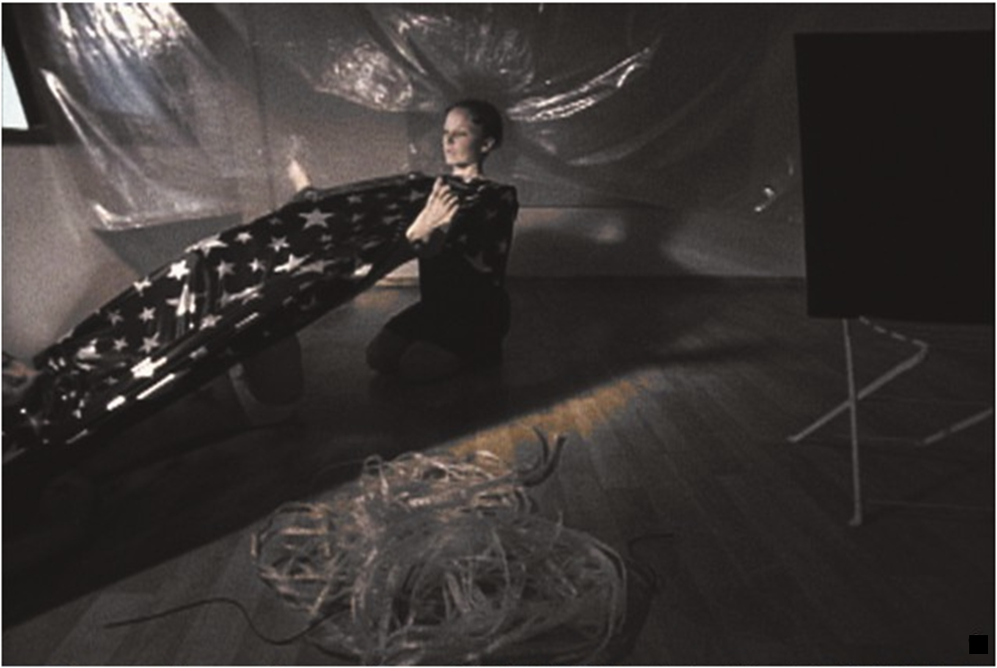

In fact,

proposing Room 2 as an editing room and studio, the artist plans to conduct,

throughout March, various performances and workshops with creators from

Australia and Korea based on scripts he wrote, and to record and film them.

Given that footage created in a specific time and place may appear in a “new”

work the artist will conceive in the near future, it stands in a mutually

referential relationship. As Head Is the Part of the Head redefined

the moment of “now” by using a live-photo technique on a mobile phone, perhaps

the artist aims through Untitled to redefine the

“now” of an exhibition bound to a specific period.

Among

the A Record of Drifting Across the Sea materials

posted on the artist’s website are many excerpts from Roland Barthes’s Neutral.⁴

Of these, Barthes’s description of the gesture of “unthreading” from an

entangled object served as a key conceptual metaphor for this exhibition. But

if we look at the passages before and after the sentence in which that phrase

appears, we find that the act of unthreading is not to explain or define the

object of thought but to “describe” it, which is to say, a state of capturing

“nuances” that are similar but subtly different.

Likewise, the framework

(structure) of thought activated by the artist around A Record of

Drifting Across the Sea can be seen as an attempt to carefully

unthread an intricately tangled skein of thought and to capture, from the

present standpoint, the nuances of resemblance within difference that exist

among objects that seem dissimilar. Writing and reading the records of

learning—the moments of “knowing”—《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o

ia e ia》 is therefore experimental and, at the same

time, practical.

1 Artist’s

website https://sunghwankim.org/study/lessonsinthefall.html

2 Gahui Park, exhibition leaflet for 《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o

ia e ia》, Seoul Museum of Art, 2024, p.45

3 Sung Hwan Kim, “Project Statement Written in 2019 Before the Work Head

Is the Part of the Head,” in 21GB, Gwangju

Biennale 2021

4 Roland Barthes, Neutral, trans. Rosalind Krauss and

Denis Hollier, Columbia University Press, 2007, p.11