The

second video, A-DA-DA, introduces two male performers

of the same age who appear to be brothers or friends, having them play father

and son; narrated from the son’s perspective, it proceeds with an

unintelligible father who, drunk, orders the son to “strip,” etc. When they exit

that everyday space, the two, apparently on equal footing, carry out assigned

tasks in a kind of work space. This reduces identity to a given role, making us

read the intention somewhere in between (their mere existence as performers).

The language—foreigners appropriating a Korean’s tongue—awkwardly segments and

slips from normal speech; this relates partly to the implication of “stutterer”

in “A-DA-DA,” and, though we might surmise it connects to the artist’s

childhood memories and to experiences abroad as an outsider, first of all it

reveals language not as embodied speech but as script/lines—the language of a

kind of mimicry—exposed along with the acting of the two actors. It is an

experience in which the border of a foreign land is engraved upon ourselves.

That is to say, the decisive point at which these two who look Korean or Asian

(but are actually Asian foreigners) become estranged is, precisely, language;

from this, the illusion comes undone of their outward appearance, and, as if it

were a voice immanent to the body, it transfers to us.

It seems a decisive

intention of this video to transfer to us this body fissured from a fissured

voice. Calling “father,” recalling him while looking at the sea, the son’s

close-up (speechless) back disappears without words. At a time when some time

has passed without the father, this scene—in which the father is embodied more

than the son himself—is realized in the overlap of narration, the empty body,

and the sound of waves. After the camera suddenly shifts its point of view to

the sea, where many people are playing, Cho Sang-hyŏn’s

“Eyes of

Simcheongga”

is juxtaposed, giving emotional shock. Like end credits rising, languages of

the scrolling text leave a distinct mark on the surface and fade. (As with

incorporating the domain of meta-exhibition as a kind of explanation into the

exhibition to construct an exhibition-specific context, this seems to be the

artist’s capacity to make form itself into content with form.)

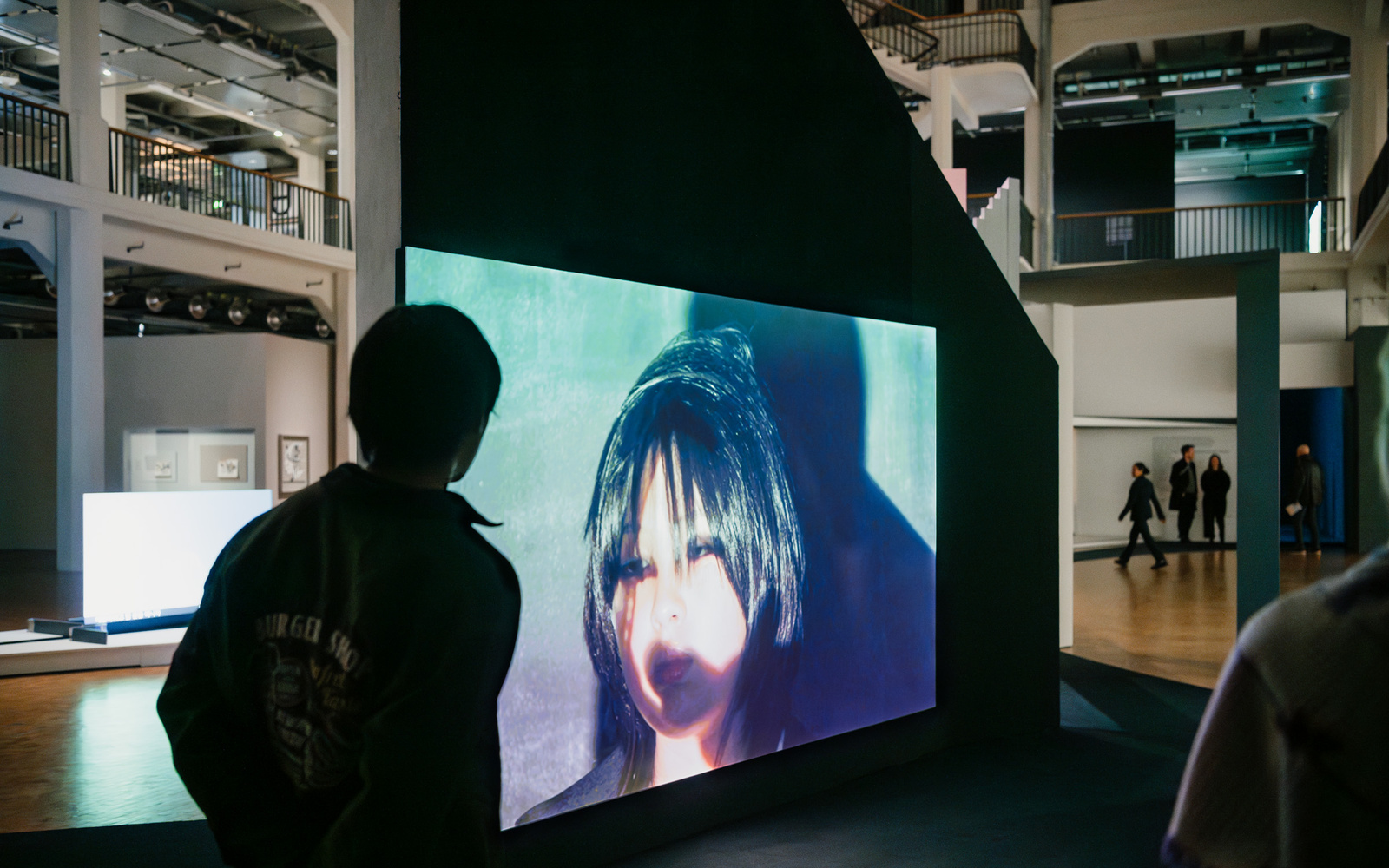

These

two videos are seen upon a black carpet (or boundary); the black carpet is not

merely the floor but a plane of space, incorporating one into the exhibition’s

context. Thus, even when sitting on it—when overlaying the body upon the

laid-down installation, a rectangular frame as looking, and the floor of

space—one is made to feel discomfort. You cannot help but overlay yourself

uncomfortably upon the exhibition; panels are woven from a single line segment,

so inside and outside are not separated but only distinguished, giving

confusion as to whether you are entering or exiting. This applies particularly

to watching Manahatas Dance at left, which is

installed smaller than A-DA-DA, and the space

partitioned smaller accordingly.

Exiting this space, there is a rectangular

black frame (as painting, installation, architecture) which you cannot avoid

stepping on to reach the next space for A-DA-DA; next

to it a blue structure overlaps slightly, and since its side is the same color

as the wooden frame you cannot gauge its height and may stumble. Lighting

dropped intermittently from above (none of the original gallery lighting is

used; the exhibition is composed only with lighting within the installation),

structures that stand while giving light as a kind of gaze-body, and wooden

rods floating in the air resist full flatness and scatter the gaze.

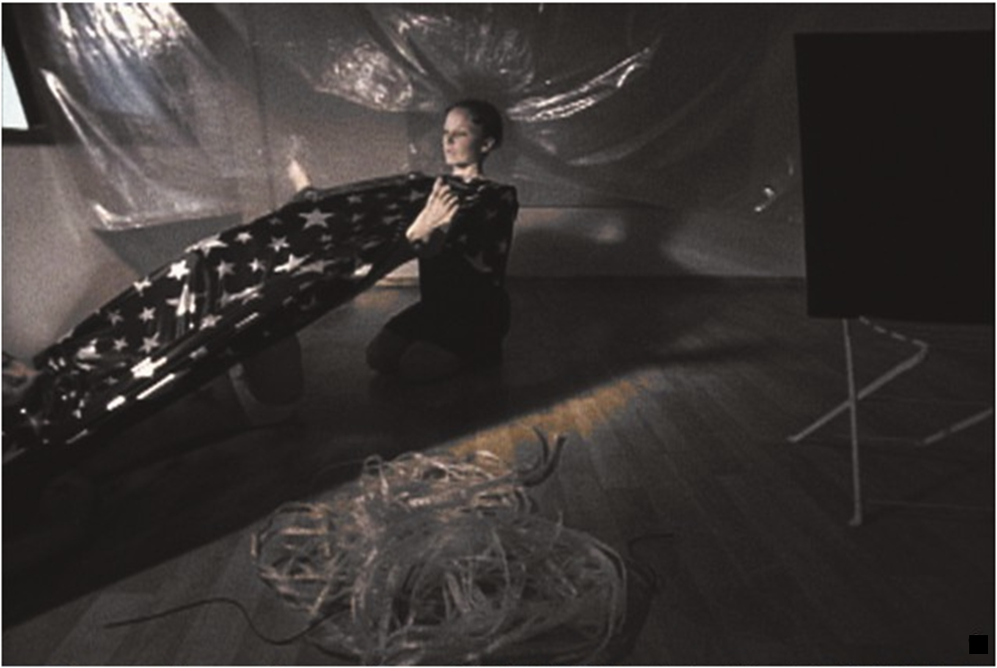

After

an experience not wholly reducible to video, painting, or installation, on the

third floor you face, instead of the hole/door/boundary entrance of the second

floor, a dark panel-boundary that initially blocks and makes one hesitate to

enter; riding along this narrow boundary into the space, you discover the site

from which to watch the video and confirm the architectural prospect. Echoing

the opaque frame of the entrance, it places the gaze and body at the beginning

of a sight that can look (rather than of looking). And the beginning of

obstruction is a screen not yet in view from that place—the state is yet

unopened.

Now, with only the sound delivered by the video at your back, you

move away from the screen; meanwhile you step on the black carpet as a black

screen and walk quite a distance (almost from the entrance to the far end of

the hall— giving a sense of excessive expansion compared to the second floor’s

spatial experience), take your place in the narrow seating, or sit on the black

carpet before it, and see Temper Clay. The artist

explained that in his videos (whose fragmented narrative traces form their

trajectory) only the words “temper clay” may remain in the viewer’s memory as

such—thus the artist’s thought differs from communication theory in which form

is a medium that contains identical content under a single code, asking how

well the artist’s thought has been conveyed and expressed. Here “temper clay”

for the artist is, as a signifier, meaningful in that it was remembered as

such.