It

is no easy task to know and enjoy the intellectual and formal processes through

which these became artworks and an exhibition, passing through investigation

and execution, distillation and synthesis.

Here

a primal question may arise. Why did Kim choose Hawaii for such work? Setting

aside the viewer’s difficulty of artistic reception or intellectual

understanding, why is the subject of this arduous multi-study art—one that

demands from the artist himself immense energy and resources, time and

performativity, both mentally and physically—Hawaii? How can the image of

“Hawaii as a resort,” etched in people’s minds, be broken, and how can the

artist—and we—reveal what truly must be known about that place?

From

a critical perspective, the agenda can be grasped thus: First, that Hawaii was

originally islands of the Polynesian natives and bears deep historical

vicissitudes until its annexation as the 50th U.S. state in 1959.

Second, that it is a space connected to Korea’s independence movement history

and to the history of Korean immigration to the United States in the late 19th

and early 20th centuries. Third, within Kim’s artistic view, Hawaii functions

like an electrode space, attracting and repelling, as it were, the U.S.

immigration histories of independence activist Ahn Chang-ho (Dosan), his wife

and sons; the “homeland” of composer Isang Yun; the “experience of leaving

Korea” conveyed by the Korean-German writer Yi Mirŭk in The Yalu Flows;

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s

experiments on language and gender with the characters for “male” (男) and “female” (女) in DICTEE;

and the issue of borders and movement, evidenced as public documentation by the

“passport issued to Kim Sun-geon in 1903 for emigration to Hawaii.”³

The

artist embraced Hawaii as a metaphorical episteme (space of knowledge) in order

to examine and construct knowledge about vast and complicated matters that are,

each of them, but broken fragments of the past. From the standpoint of an

artist from Korea who has drifted across North America and Europe, to know the

“other language” of exiles or those who “emigrated in an unexpected era” is the

bone of A Record of Drifting Across the Sea, and the

flesh realized in 《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o

ia e ia》.

No hea mai ‘oe

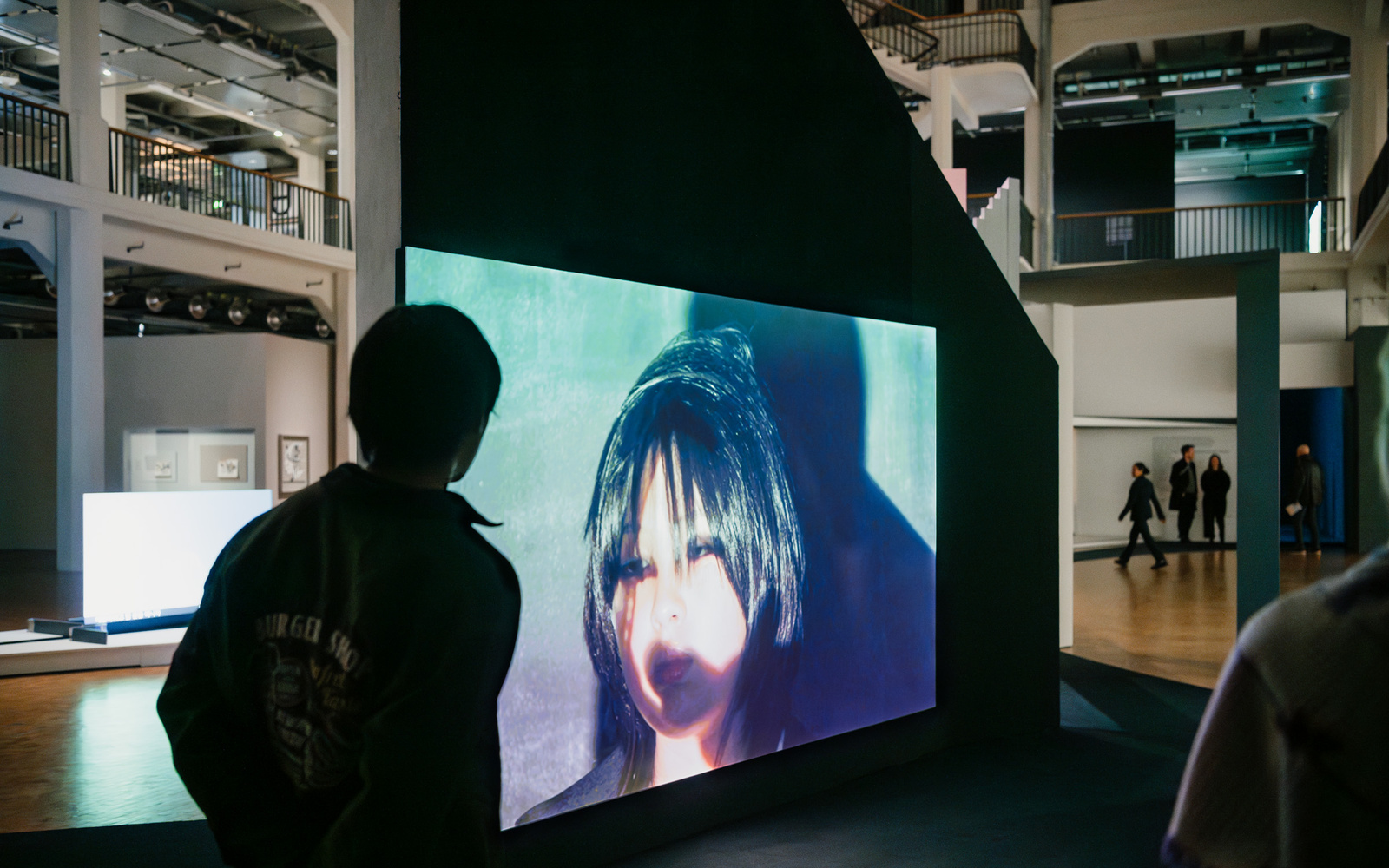

One work that especially draws attention in this profound exhibition—one with

which viewers may intuitively empathize—is the series Body

Complex (2024). It is an installation occupying a wide inner

area of the 2nd-floor exhibition hall (“Room 1”), where photographs of the

statue of Dosan Ahn Chang-ho we learned from the history of the independence

movement, and low-resolution images resembling video stills of Asian men and

women, stand on pillars like signboards in an Independence Hall education

section.

Looking closely, we find texts indicating that these images include

Ahn Chang-ho’s wife Lee Hye-ryeon (1884–1969)—herself an independence

activist—their eldest son Philip Ahn (1905–1978), and Bae Han-la (1922–1994),

who emigrated to Hawaii in 1950 and taught Korean traditional dance there, as

well as her local student Mary Jo Freshley (1934– ). It is, in fact, only while

seeing and reading these that we begin to sympathize with the weight of meaning

in Kim’s undertaking of A Record of Drifting Across the Sea.

Though it may invite the response “pedantic,” in my view this work illuminates

Hawaii and colonized Joseon’s independence movement; women and children

bracketed out of the male-written narrative of that movement; the hardships of

immigrants that cannot be summarized in a few lines; and, nonetheless, those

who realized fusion and hybridity on site by enlivening their cultural

identities.

Regarding

this work, Kim explains it as “a space of translation that can be created when

two or more languages enter.”⁴ This is a statement that metaphorizes his

own Body Complex as a space, while also defining

the particularity of Hawaii’s geographic and politico-cultural space. More than

two languages and nationalities; more than two races and peoples; more than two

bodies and genders; more than two classes and lifestyles…. If there is a place

that exists with such multiple and hybrid qualities, then, for better or worse,

people are exposed in everyday relations to the question, “Where are you from?”

or “Where do you belong?”

In

Hawaiian, that phrase is pronounced and written “No hea mai ‘oe?” The very

starting point of what Kim seeks to know in the creative endeavor of A

Record of Drifting Across the Sea, and the depth of the horizon of

understanding he seeks to share with viewers through 《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o ia e ia》, is precisely that

question. Why do we ask each other, “Where do you come from”—why do we inquire

into each other’s origins? Nowadays we think such a question is an aggressive

and rude approach that invades another’s private domain. Beneath such speech

lurk dangers of discrimination and exclusion, and so this is a meaningful

shift. But from another viewpoint, it is a forming of relations premised on

absolute respect and recognition of the other.

That is, a coming-to-know in a

companionate relation that advances while acknowledging difference between me

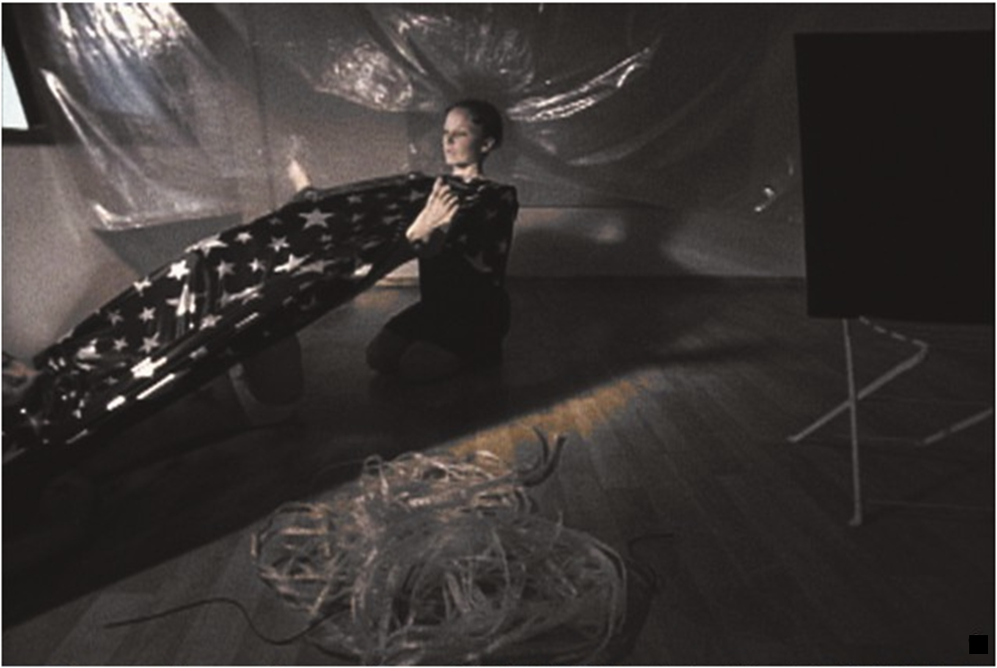

and you, between my ground and yours. Etched in my mind is the image of an

elderly Mary Jo Freshley beautifully dressed in a cream-colored hanbok, dancing

Korean traditional dance in a sunlit studio. It is a trace of being contained

in Kim’s video work By Mary Jo Freshley. And for me, it

is a thought-image representing the overlapping and connection, the coexistence

and orientation, of “Korea–Hawaii.”

1

“The Tanks Commission: Sung Hwan Kim,” Tate, 2012. 7.16. https://www.tate.org.uk/press/press-releases/tanks-commission-sunghwan-kim

2 https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5308

3 The above quoted phrases are sourced from “Sung Hwan Kim/David Michael

DiGregorio Interview (Interviewer: Max-Philipp Aschenbrenner),” Asia Culture

Center Web Whale, 2015. 7, https://sunghwankim.org/study/womanhead.html; and from the work descriptions in the leaflet for the exhibition

《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o ia e ia 우아 아오 이아 오 이아 에 이아》, Seoul Museum of Art, 2024.

4 Exhibition leaflet for 《Ua a‘o ‘ia ‘o ia e ia 우아

아오 이아 오 이아 에 이아》.