Seoul

is an urban landscape that changes before your eyes—a city of a kind of liquid

architecture that gets destroyed as quickly as it gets built in a cycle of

defamiliarization and discontinuity. Navigating the city, as anyone who has

visited Seoul will know requires a relationship in which the past, present and

future co-exist in simultaneous space. For instance, when you ask a cab driver

to take you somewhere, addresses usually prove to be useless, but he will often

ask you “oh, is it where Building X formerly was, which used to stand next to

Building Y and where Building Z is currently under construction?” Seoul, like

many cities in Asia that went through rapid industrialization, operates within

the rhythm of a time-lapsed video.

In this intricate and densely woven weave of

roads, public transport systems, underground tunnels, and overhead highways,

entire neighborhoods are eradicated and communities uprooted and displaced en

masse for innumerable development and redevelopment projects, altering the city

landscape like the unrecognizable face of a chronic plastic surgery patient

constantly under helm of the knife. It is a patchwork that never quite comes

together where histories, memories and everyday realities are held together by

fragile seams.

“My

sense of time does not follow the common sequence of past-present-future, but

rather of past-future-present.”1

This

is where Minouk Lim’s work begins. Over the past 15 years, Lim has developed a

provocative body of work that critiques the social and political conditions of

a contemporary society fueled by rampant growth and development. Interested in

the silent, invisible, and peripheral aspects of industrialization—what the

artist calls “the ghosts of modernization,” Lim responds to the loss of

belonging and place. Her work unabashedly moves from declarative gestures of

protest to symbolic rituals of mourning.

Consciously working between the lines

of aesthetics and politics, Lim’s works create spaces where dissent

necessitates new ways of seeing and experiencing. Deeply influenced by the

writings of Jacques Rancière(1940-) who defines ‘the political’ not by the relations

of power or the achievement of a specific goal, but rather the active process

of creating disruptions within consensus driven culture, Lim’s works operate as

‘dissensus,’ using Rancière’s term, or as interruptions to the political and

boosterism rhetoric that pervades contemporary Seoul. For Lim, occupying a

position of dissent demands a recalibration of our cognitive and sensorial

processes, necessitating a different way of seeing and perceiving that

recaptures collective memory and implants a conscience within the experience of

lived reality.

“My

ethical responsibility of art is an issue that draws attention from a number of

artists. My stance is close to that of Jean Luc Godard(1930-)’s Le

petit Soldat (1963) who said “Ethics is the aesthetics of the

future.” I am interested in the sentimental judgment phenomenon, which has

moved from ‘the good’ in truth and beauty to ‘beautiful.’ I believe that this

is the same as looking into how our world holds disharmony together; it is

because an action has to reorganize the sentiment about what cannot be seen,

what cannot be heard and what cannot be spoken, as Jacques Rancière had

claimed.”2

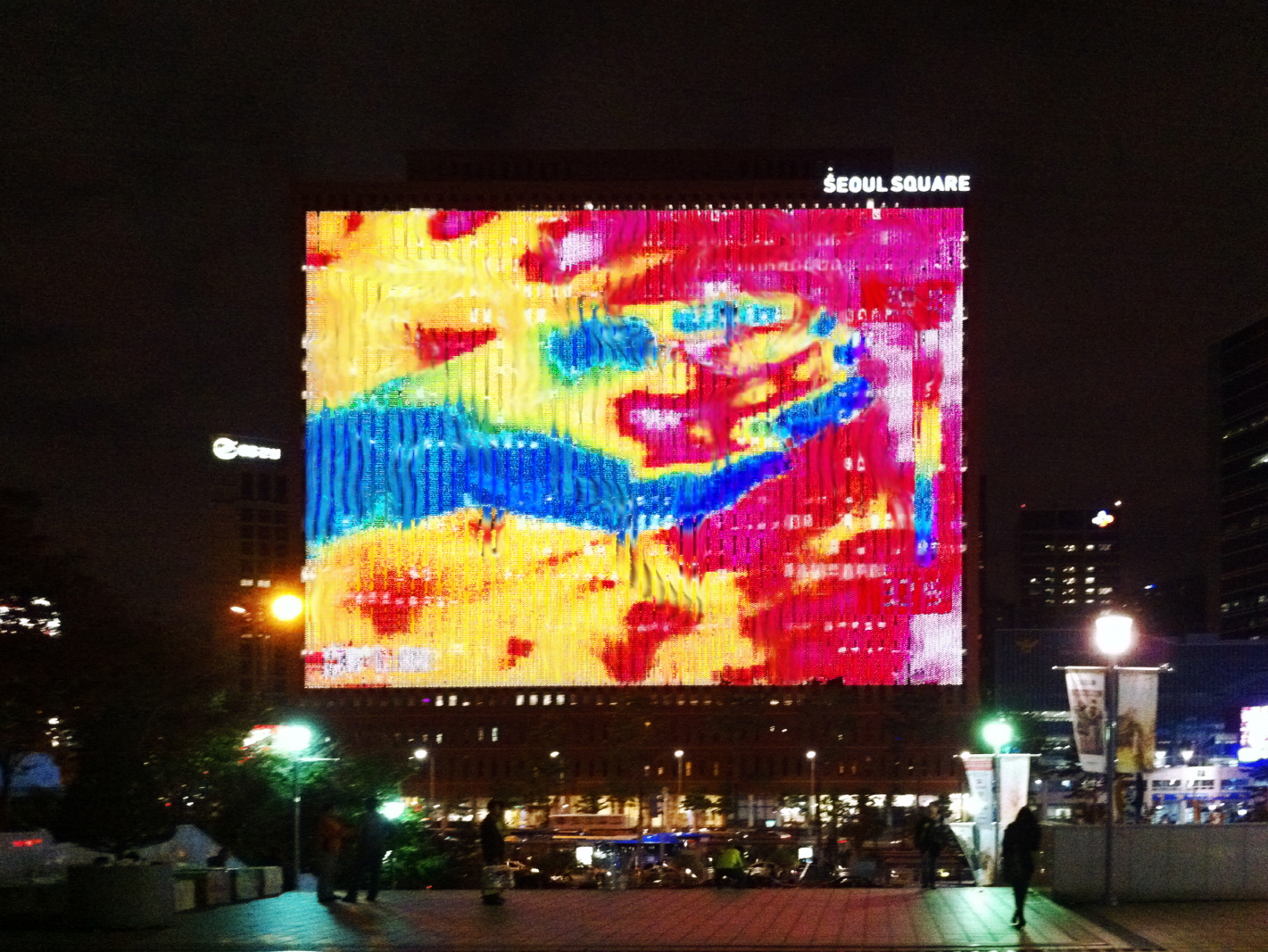

In

recent years, Lim has acquired a distinct visual language that provocatively

melds her interest in performance, video, and documentary. Commissioned by the

BOM Festival, S.O.S.-Adoptive Dissensus (2009)

takes the form of a three-channel video installation of a light and sound

performance that originally took place on a cruise ship along the Han River.

What Lim describes as a “performance documentary theater,” S.O.S. is a

multi-layered work that is an immersive sensorial experience with searchlights

scanning the nightscape of Seoul as an audience on the tourist cruise boat (or

the audience of the video installation) are taken on a journey of the unknown

to the 25th hour.

The long time captain of the cruise ship becomes the narrator

of this journey in which lost histories and memories wiped out by urban

development initiatives like the Seoul city government’s ‘Miracle of the Han

River’ project are recounted. Using real time, two-way radio, the audience come

into contact with three performative vignettes that happen on the banks of the

river: a group of student protestors in arms, two lovers who recount their

emotional ties to Nodeul Island, and a former political prisoner of conscience

recounting his personal story of struggle. Together, they trace a narrative of

the individual lives and personal memories, from different times, places and

social contexts collapsed into the space of one work, in an attempt to humanize

the cost of modernization.

“My

work throws the question on the relationship of memory faded by speed,

resistance from it and the relationship between human beings and nature inside

the city. This rapidly changing environment erases our memories and we have to

prepare ourselves to let go of the memories without making them. The dizzy

process of ‘globalization’ seems as though ‘we have already seen it’ and ‘we

have already lost it,’ while wondering about the restless time.”3

Reinventing

documentary as a form of direct engagement, Lim upholds the importance of the

audience in her work as witnesses to the dissenting voices of history. For the

artist, seeing is the act of sensing and touching—a poetic achieved by the

embodiment of real time and space. If S.O.S. used sound and searchlights

to capture lost spaces, The Weight of Hands (2010)

uses the infrared camera, typically deployed for military surveillance

purposes, as a literal and metaphoric tool to penetrate through a cordoned off

construction zone. The work operates as a funerary ritual of sorts, in which a

group of sojourners on a tour bus, attempt to break into a restricted space of

development.

The haunting video is punctuated by a woman passenger on the bus

who is raised up and passed from person to person, while singing a ballad of

loss, hopelessness and alienation, while the infrared camera footage records

temperature and heat as a series of brightly colored abstract patterns in

different hues and intensity. They are the literal and metaphoric stand-ins for

lost bodies in space, in a context where physical spaces are restricted or no

longer available, the work considers us to use other sensory devices—touch,

temperature and heat as a way to see and experience our reality. The use of

infrared camera would figure again in Lim’s subsequent work, becoming the

technical device that carries and furthers her ideas of perceiving beyond

physical attributes, of charting the traces of human existence.

“Today,

under the changes caused by globalization, places are counted only as space;

individuals are merely resources for networking. Nietzsche was said to have

wept as he embraced a downtrodden horse, but I want to weep, embracing places.

Nevertheless, I also want to fight against the sense of powerlessness caused by

melancholy, whether is it the feeling that overwhelmed Nietzsche, or any other

kind. So I am inventing rituals for, and keeping records of, moments of

separation.”4

Lim’s FireCliff

performances, now three in the series, extend her interest in the relationship

of the body in the city, of the witness to phenomenon, of placeness and

history. The first was performed at La Tabacalera in Spain in 2010—a cultural

and community center in a former tobacco factory building in Madrid. For the

performance work, Lim interviewed former female workers of the tobacco factory,

relaying their stories, their working conditions and eventual lay off and

performed their texts in what she calls site-specific installation and sound

performance with hip hop music and other sounds and light effects.

For Lim, the

work is an effort to rekindle the history of place, to uncover the stories that

are buried deep in the ground or embedded in the walls of the

building—forgotten as new lives pass it by. The FireCliff performances

are rituals of sorts that summon the past, present and future in precarious

ways. FireCliff 2_Seoul (2011) was performed on

the occasion of the 2011 BOM Festival in Seoul. Interested in the relationship

between memory and testimony, Lim realized the performance in a more classical

theatrical configuration, with audience and a stage set up in a building

formerly used as a security intelligence complex. The performance featured two

individuals: Hyeshin Jeong, a psychiatrist and Taeryong Kim, a long time

political prisoner (who Lim had met while working at the Truth Foundation) and

the space of the theater was turned into a documentary space—in which the drama

of one’s own life, lived and performed by that person, unfolds to an

audience.

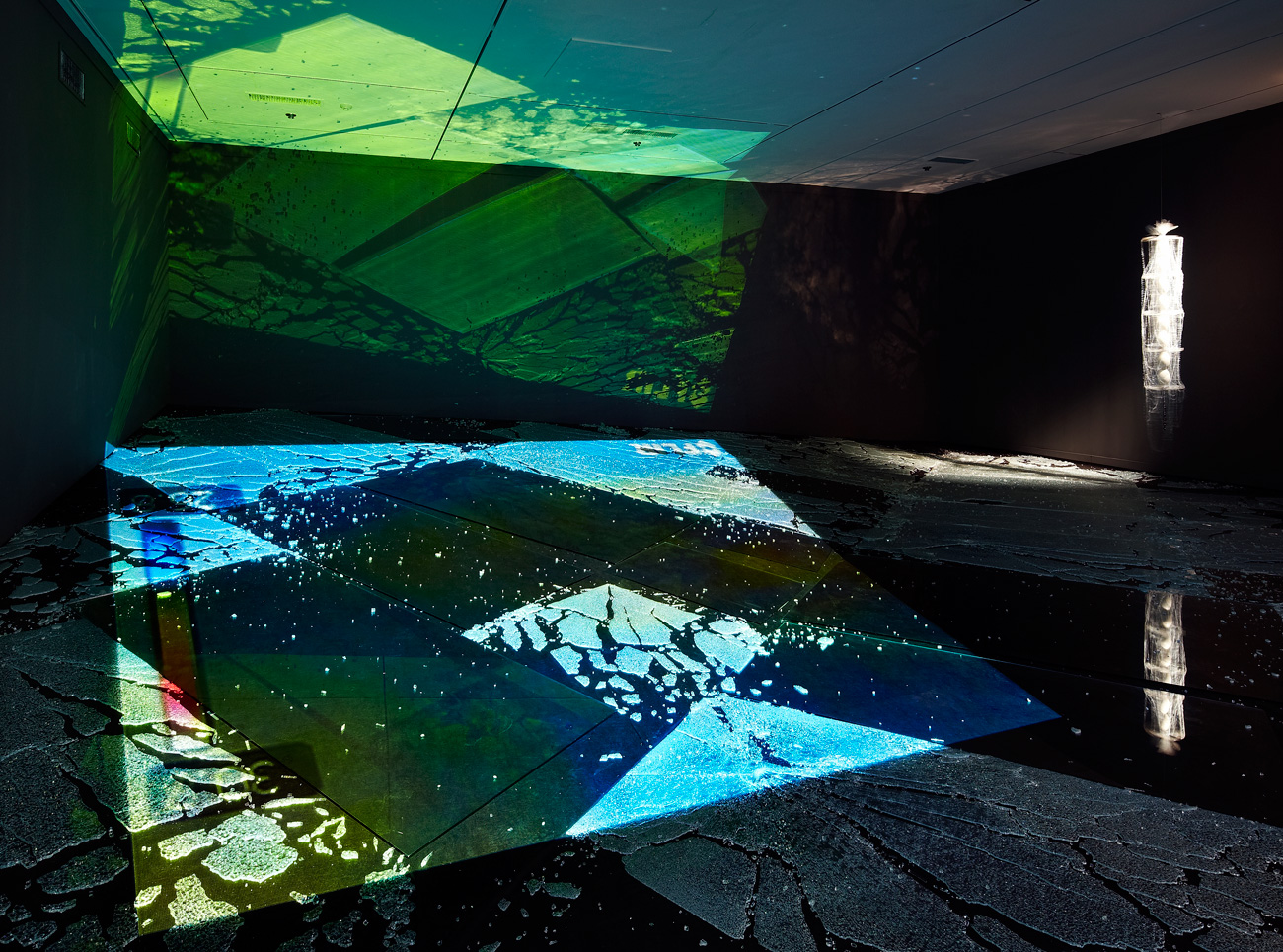

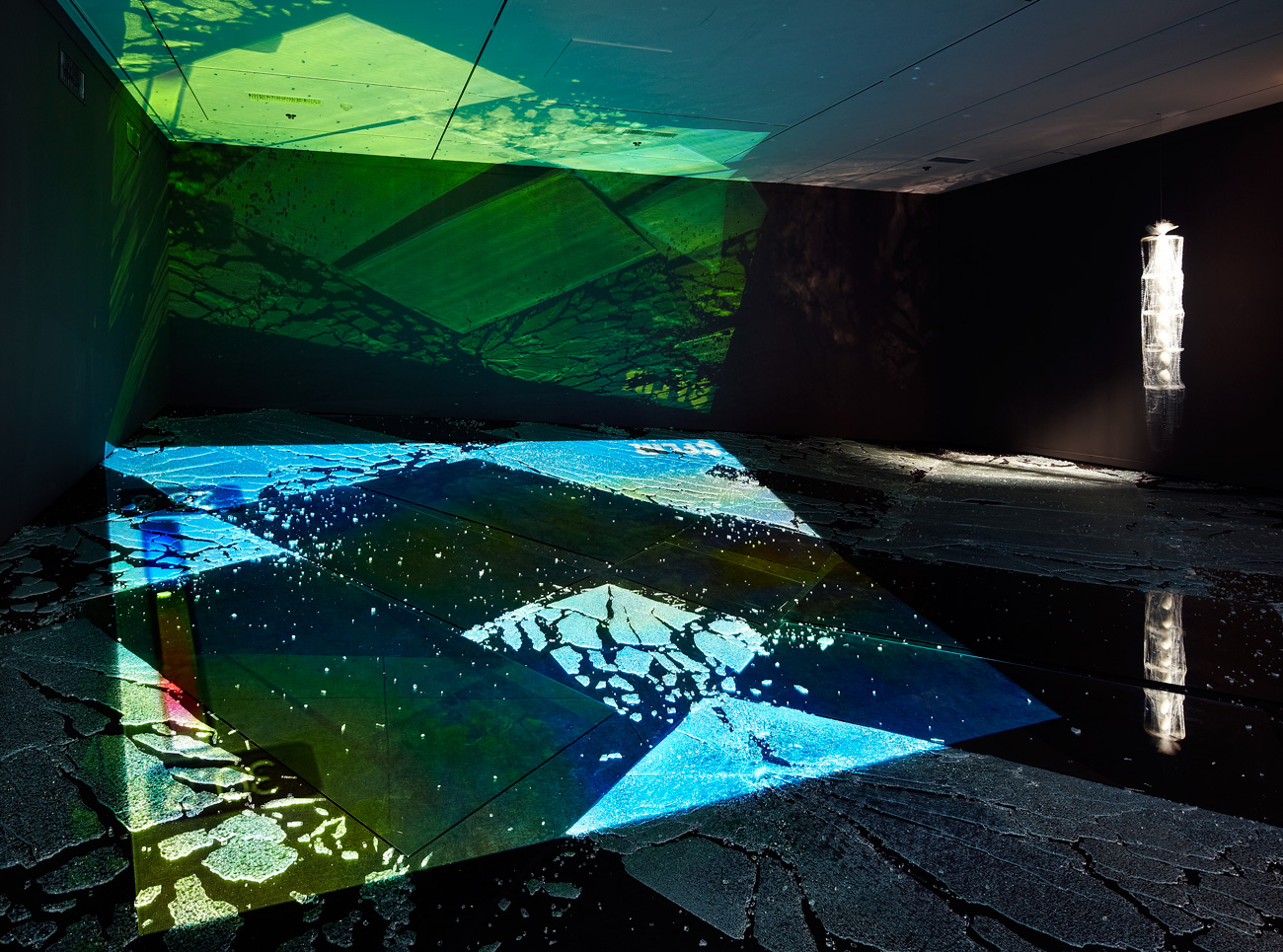

FireCliff 3 (2012) was performed on the

occasion of Lim’s exhibition at the Walker Art Center in 2012 and went step

further in the integration of choreography, dance and sculpture. As a

continuation of Lim’s interest in the space of theater, performance and movement

as invoking the active participation of its participants, Lim worked with a

choreographer in creating a movement based performance around an imagined

apocalyptic landscape. For the first time, she incorporated sculptures in her

performance—a newly commissioned series of totemic forms (which appeared first

in her video Portable Keeper (2009)) and wearable

sculptures.

Inspired by André Cadere(1934-1978)’s wooden bars, Krzystof

Wodiczko(1943-)’s homeless shelters and Hélio Oiticica(1937-1980)’s parangoles

as well as the recent nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Lim created these

biomorphic forms from thermofoam and other scavenged organic and synthetic

materials as protective shields and devices for the body within an apocalyptic

landscape. For Lim, they represent the desire to defend the collective

consciousness within a terrain of shifting forces and uncontrollable ambitions

while advocating for a deeply humanistic position of empathy, sentiment and

resistance.

“We

are all born into a theatre. I even consider the womb to be a stage – a liquid

theatre. After we’re born, we build a concrete theatre. Half of life is acting

in a fiction, and we all consider our roles in reality. I’m not satisfied with

the common definition of ‘role.’ I always hear these questions: What is the

artists role in society? The father’s role? Mother’s role? Professor’s role?

These roles have been more and more reinforced. I would like to rediscover the

notion of roles in order to question how much is reality and how much is

illusion. So, I’m not thinking about blurring a borderline, but rather a

coexistence of fact and fiction. In theatre we talk about an actor as an

instrumentalized body, speaking someone else’s script, but I am using the term

in its more active definition. As an actor, we have potential to decide our own

role.”5

Lim’

most recent work Liquid Theater (2012) which

premiered at the La Triennale Paris is a video-based installation that consists

of totemic sculptures (aka Portable Keepers) and a

video. The work takes video footage of the recent death and funerary

processions of Kim Jong-Il(1942-2011) as well as archival footage of Park Chung

Hee(1917-1979)’s—the two eerily undistinguishable, as well as incorporates

Lim’s thinking about Fukushima and the rise of suicides in South Korea. Images

of public mourning become stand-ins for private mourning—for the loss of lives

that are not commemorated or counted, whose deaths also has the right to be

mourned. For Lim, the mourning images, though rooted in fascist ideology, have

a primitive quality or rather represent a primitiveness in our humanity.

By

bringing this footage together with explosions, Liquid Theater presents

a possibility in reversing the repercussions of tragedy, in this case how the

death of Kim Jong Il might present a beginning rather than an end. To that end,

Lim imagines a tropical Korea represented by footage of her daughter on the

Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, so seemingly distant from the specificities of

Kim Jong-Il and Park Chung-Hee, but in fact rooted through the biography of her

child. She envisions a tropical Korea, a mise en scène of a tropical extreme

that creates a new imagination through the destruction of old ones (its

political ideologies and capitalist ambitions) and in doing so aims to dispel

the false rhetoric of progress by returning to a primitive state where things

might become possible again.

“I

would like to track the cultural entangling from the modernization period,

something primitive and original, but neither unique or common. I would like to

tell a story beyond what we see, hear, know and believe to know. It seems that

there is a place where the original spirit of the media resides. It is my

belief that the nature of art should be set against the hegemony covering a

wide range of genres, and the politics should also be the same.”6

1.

Minouk Lim, “The Heat of Shadow,” Walker magazine (June 2012)

2.

Minouk Lim, “Art Talk, Lim Min Ouk: Taking a Pause—A Methodology to ‘Confront’

Intangible Objects,” SPACE magazine (January 2011)

3.

Minouk Lim, 2009, unpublished

4.

Minouk Lim, “The Heat of Shadow,” Walker magazine (June 2012)

5.

Minouk Lim, “Take-Out Performance: Minouk Lim in conversation with Jody

Wood,” movementresearch (March 2012)

6.

Minouk Lim, “Art Talk, Lim Min Ouk: Taking a Pause—A Methodology to ‘Confront’

Intangible Objects,” SPACE magazine (January 2011)