Aporia of “Authentic A Cappella Music”

The

term “a cappella”—literally “in the style of the chapel” or “in the church” in

Italian—refers to a form of playing or performance that involves only the human

voice without instrumental accompaniment. This musical form, which most of us

could have heard at least once in high school, college, or church, or have

experienced while taking a shower with no awareness whatsoever, has finally

escaped the tiny confines of devoted music aficioados since the 1990s, when the

American black vocal group called BoyzIIMen gained global popularity. Through a

series of meandering occasions, I got involved in an a cappella group myself.

Our groups was fortunate enough to sell nearly 400,000 copies of our debut

album and release a few more before I left to study abroad. It was during this

period when I came across the existence of a broad “a cappella scene” in the

English-speaking world.

The most striking thing I encountered then was the

debate over how much artifice should be allowed in a cappella music. At stake

was the idea that since a cappella itself excludes instrumental accompaniment,

a song or album by a group with overly mechanical sound effects could not be

considered a cappella. This argument was soon forgotten, however, as there is

no recording without machines. If we remove the non-human elements to argue

that only purely human voices constitute “authentic a cappella music,” then no

recordings should be made, and we end up with the doomed self-contradiction

that the songs of people living in different regions, countries, and continents

cannot be heard except in person on the spot.

The debate in question is absurd

from the outset, in the sense that the phenomenon of sound itself is inaudible

without the medium or transmission mediums such as air and space. This is not

unlike the fact that the dynamic sound effects in movies like Star Wars,

especially in battle scenes taking place in the vacuum of outer space, where

there is no air, do not make sense in principle. Sound is inherently

inseparable from its media. Allowing any sound to be made and heard in the last

analysis, media amounts to the sound’s ultimate condition of possibility.

Reverberations of this realization have continued to resonate in my exploration

of the medium’s relationship to art in general, beyond the seven years of choir

conducting at a small church while studying in the U.S.

The

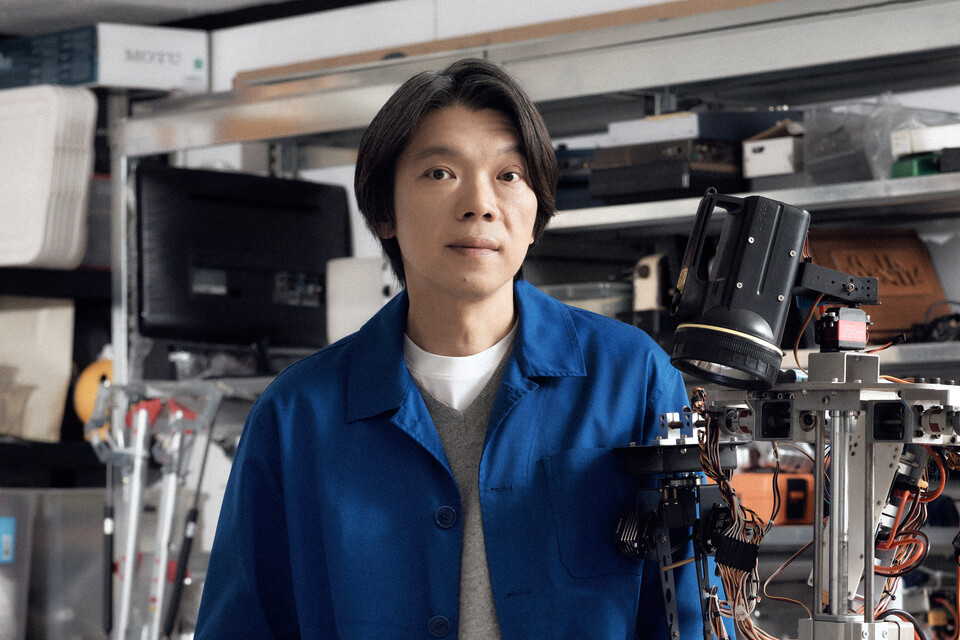

exhibition of Byungjun Kwon, the Winner of the 《Korean Artist Prize 2023》, serves to summon

this long-standing thread of memory, both private and public. It is not

unrelated to the fact that this exhibition, and his entire body of work, is

organized around two main axes: sound and machines. Let’s take the voices that

have become familiar amid the acceleration of the AI frenzy since last year.

Beyond the cover of the K-Pop sensation NewJeans’s hit “Hypeboy,” which sounded

like it was sung by Bruno Mars, or the American musician Weeknd’s “Starboy,”

which must have been sung by BTS’s Jungkook, there are various versions of

BIBI’s hit song “Bam Yang Gang,” which made virtually everyone think of the

superstar IU and comedian Park Myung Soo even when they did not sing it.

These

voices highlight how the so-called “natural voices,” once considered unique to

humans or specific individuals, have become more indistinguishable from the

artificial than ever before. Clunky rather than smooth, more manual than automated,

Kwon’s works appear far removed from these cutting-edge, post-human sounds.1 At

the same time, however, his work does not maintain an intimate relationship

with “natural voices or sounds” either. Paradoxically this remains a point that

has been consistently overlooked in the emphasis on his ongoing interest in

so-called “minorities,” such as Yemeni refugees and Korean multicultural

families.

To be sure, that he conceived of robots as the vanishing point of

these heterogeneous beings, the “strangest stranger,” and presented them in

this exhibition as “minorities and companions in human society,” recalls the

self-evident fact that refugees and migrants are heterogeneous. Nonetheless, it

is difficult to argue that refugees and migrants are literally “mechanical.”

Mechanical things are heterogeneous, but not all heterogeneous things are

mechanical. One must not confuse the two, for then we hastily reduce the entire

construct that Kwon has been meticulously crafting and expanding for more than

two decades to a crude statement calling for “accepting the Other.”

This

is not unrelated to the fact that, albeit often conflated with “music,” sound

is a larger category, and that machines, or automatons, are also often thought

of as “humanoids,” i.e. robots based on human form and function, yet

irreducible to them. This somewhat simple stipulation harbors important

implications in correcting the biased response to the exhibition focusing

mainly on the representation of robots2 and capturing the

broader resonance of Kwon’s oeuvre. This is not to say that robots are insignificant,

but that the intrinsic relationship between the music in the expanded sense of

the term, fed back through the concept of sound, and the mechanical in Kwon’s

works must be grasped much more rigorously.

For instance, it is true that John

Cage’s 4:33 is the most famous example of the silence or

“impossibility of perfect silence” that suggests sound beyond the narrow

confines of music. Perhaps more relevant to the discussion of Kwon’s work,

however, is the poignant recollections of Philip Glass (b.1937), a leading

minimalist composer and film composer whose work ranges from the experimental

ethnographic film Koyaanisqatsi (1982) to

Hollywood films such as The Truman Show (1998)

and The Hours (2000) to Park Chan-wook’s The

Stoker (2013).

Bob Dylan, Philip Glass, or Byungjun Kwon

In

1967, shortly after graduating from the Juilliard School and spending three

years in Paris, Glass returned to New York City. “The biggest thing I heard,”

Glass admitted, turned out to be the “amplified music at the Fillmore East.”3 The

Fillmore East, then a popular Rock and Roll venue, played music by Jefferson

Airplane and Frank Zappa, among others, and he became “totally enamored with

the sight and sound of a wall of speakers vibrating and blasting out

high-volume, rhythmically driven music.”

Of course, the watershed moment and

impact of the amplified sound of the Rock and Roll had already come two years

earlier. It was in July 1965, when Bob Dylan appeared at the Newport Festival

and played his 1964 Sunburst Fender Stratocaster. As is well-known, many fans

felt utterly betrayed by Dylan at the time. The audience, feeling that Dylan

had abandoned the image of a leading figure in “folk music” that he had

cultivated during his two previous back-to-back festival appearances, expressed

their anger with loud boos and insults. It is intriguing to note that the audience’s

negative reaction was not unrelated to the fact that the lyrics of the songs,

deemed central to folk music, were barely audible due to the amplified sound of

the electric guitar.4

Folk-blues guitarist and music historian

Elijah Wald even elevates the event to the watershed moment that split

America’s 1960s in two. With Lyndon Johnson implicating the U.S. deep into the

Vietnam War and the rise of “black power” rendering the whiteness of the civil

rights movement acutely visible, the “communal feelings” of the first half of

the 1960s had effectively imploded. It was at this precise juncture in which

Dylan, then widely regarded as the head of that emotional community, exploded

it, in terms of a flat-out, if compressed, rejection of the imposed role.5 This

signifies that the overall effect of the amplification of mechanical sound on

classical music lovers and folk music fans alike went far beyond the rupture of

the core components of music, i.e., melody, harmony, and lyrics.

For

example, Glass’s early works Music in Fifths and Music

in Similar Motion were composed between June and December 1968,

the year after he was busy frequenting Fillmore East. As with much of his work,

they are often summarized in terms of mathematical structures and patterns

between pitches, particularly in terms of addition and subtraction. Without

denying this aspect, Glass nonetheless underscores that “a major part of the

impact of the music comes through the amplification itself,” raising “the

threshold experience to a higher level.” To those accustomed to later

recordings capitalizing on the grand piano’s crystal clear sound, it may sound

surprising.

Still, Glass memorably recalls that “[t]here was a grunginess to

them that came out of the technology that was available at the time— the

electric pianos and the big, oversized boom-box speakers.”6 Grunge?

The 1990s alternative rock of the “dirty” “Seattle sound” that combined punk

rock and heavy metal, epitomized by legendary bands like Soundgarden, Pearl

Jam, Alice in Chains, and, most notably, Kurt Cobain’s Nirvana? I don’t know

how many people can imagine Philip Glass’s compositions sound like “Smells Like

Teen Spirit.” Still, the mechanical sound that came out of the speakers’

amplifiers crossed the “threshold” of classical music in the narrow sense of

the term.7

Repeatedly

emphasizing “the new dimension added to the music by amplification,”8 Glass

reminds us that “rock,” with its mechanized amplified sounds, was not

considered “music” in the classical music world. Adding the simplicity of rock

music’s bass lines as another “minus” factor, and by juxtaposing this

simplicity with Indian music, Glass proactively redefines his own musical

identity formation process. To him, the “rhythmic intensity” of Indian music,

which he encountered through Nadia Boulanger, the “musician’s musician,” and

Ravi Shankar,9 another master he studied with during his time

in France, was not unlike that of rock ’n’ roll. Rock ’n’ roll, a novel music

form he met in his native country through this bizarre detour, became “a formal

model” while “the technology became an emotional model.”10 This

is a significant statement, not only for his oeuvre, which is often summarized

or dismissed in terms of the dry structural play of “minimalism,”11 but

also for a more nuanced listening to Kwon’s work.

In

fact, as Kittler’s exquisite observation rightly suggests (“Rock songs sing of

the very media power which sustains them.”),12 rock and roll is

a mechanical and electronic prosthesis at its core. Just as a person who breaks

or loses his or her glasses practically becomes blind, rock music, when reduced

to melody and chords, stripped of the distortion and volume of guitars amplified

to the point of tearing speakers, is no longer rock music to anyone. In this

sense, it is worth noting that in 1971, Glass hired Kurt Munkasci, who would

later become the sound engineer for the Philip Glass Ensemble and Glass’s film

scores, and wanted him “to reproduce [sound] as loud as possible, but very

cleanly, without distortion.”13

For, taking a rock-inspired

sound and pushing the volume to the threshold of classical music while

eliminating distortion is to open oneself up to the putatively plausible

accusation that one is neither Classical nor Rock music. On the one hand, this

can be seen as a move that is mindful of falling into the trap of mere

formalism or instrumental fetishization, as in the case of Yngwie Malmsteen’s

“baroque metal,” where classical music was played on electric guitar, which was

later easily replaced by Vanessa May’s electric violin and Pachelbel’s canon

played on gayageum.

The

trajectories of Dylan and Glass, who used mechanical instruments and electronic

sounds to transform the status and character of folk and classical music

respectively, provide a relevant point of contact for the discussion of Kwon’s

work. It is also not unrelated to the fact that this period coincides with the

historical genesis of “sound art,” which was beginning to establish itself in

art galleries rather than concert halls.14 This encounter,

however, is fraught with historical parallax and ironies.

The fact that the

electric guitar—with which Dylan split the 1960s into half like, if you will,

Jesus did the Red Sea beyond folk music—and the Rock music—which for Glass was

a source of liberation for classical music—have in the meantime become a symbol

and genre of an industry with a legacy that should not be treated lightly or

overlooked, now weighed heavily on Kwon. This awareness that he was not “a

musician who wanted to maintain… the tradition of Rock and Roll… and to keep

his colors endlessly fresh”15 is largely overlooked in many

discussions that uncritically link Kwon’s musical activities to his work in the

art world.

The

1990s, when he was active in punk rock and modern rock, was a time when the

aftermath of “grunge rock,” which Glass emorably evoked, reached Korea. His

subsequent musical experiments, however, were marked by a keen awareness of the

historical status and limitations of rock music, such as his move from

distorted, guitar-driven rock to “minimal house music” with Dalpalan, his

fellow traveller before becoming a well-known film music composer. Even this

attempt that culminated in the album Mozo Boy [Fake Boy] (2004),

I suspect, was perhaps ultimately deemed by him to be inevitably subsumed into

the category of “music” as part and parcel of the industry.

The well-known fact

that he discontinued all his musical activities in Korea to study sonology at

the Royal Conservatory of the Hague, and ultimately, worked at STEIM, a unique

organization that builds experimental instruments for artists, is worth mulling

over in this precise sense. For his work has consistently intervened at the

point where the music or instrument is fossilized as part of a petrified

tradition and heritage, an element in service to a narrow sense of “music.”

Détournements and Dérives of Image and Sound

Hybrid

Piano (2013), for instance, is a work created two years after

his return to Korea in 2011. It looks like a piano but sounds like a string

instrument. It is the result of modifying an abandoned and weathered piano in

such a way that the strings oscillate through the slightest tremor of the

springs. As an extension of Windbell and Landscape (2012),

which hung from the ceiling of the exhibition space, Kwon’s performance

of Sobbing Bells (2015) at the Bell Museum in

Jincheon was also an attempt to create sound by making the bells resonate using

vibrating elements rather than the usual method of striking them.

In this

manner, Kwon’s instruments produce their own sounds. Nonetheless they are no

longer something that anyone can play like a guitar or keyboard. The former

effectively renders the skills of a pianist, acquired through years of

practice, obsolete, and the latter makes the know-how of hitting bells acquired

by humans evaporate, however momentarily. Let me take this one step further. Song

for Taipei (2016) is a performance work that utilizes the

“hybrid piano.” It was performed in an exhibition space nestled in the

mountains outside of Taipei.

Foregrounding the timbre of his modified piano,

Kwon transmitted eight compositions composed on site to a panoramic view of

Taipei in hourly increments. Played through two horn speakers on the rooftop of

the exhibition center, the music was oriented toward the city of Taipei, mixing

percussion and strings, as well as digital and analog axes. Did the audience in

Taipei really hear this music, however? Was he not transmitting sounds to

nobody, with on an instrument no one except him could possibly play?

Seen

in this light, Kwon’s work may seem like the daydream of an idealist. However,

Kwon’s interventions, which seem to maintain the exterior of the given

instruments, yet oscillate between percussion and string instruments,

dislocating the place and position assigned to each, are reminiscent of the

practices of the Situationists, a group of artists active in France after World

War II. Not unlike Guy Debord’s friend who once wandered around the Harz region

of Germany with a map of London open, following the directions on the map,16 they

(in)famously sought to reconstruct reality through interventions such as giving

old movies the wrong subtitles or leaving symphonies untouched but changing

their titles. Malcolm McLaren, the manager of the Sex Pistols, has repeatedly

stated that this iconic British group, widely regarded as the progenitor of the

genre of punk rock, grew out of his study of the Situationists.17 Kwon’s

works, which coincidentally began in punk rock, no less resonates with the

modes of intervention that the Situationists labeled “dérive” and

“détournement.”

Take ‘Forest

of Subtle Truth’ (2017–19) series, a crucial centerpiece of the

exhibition. First presented in the 2017 exhibition 《Revolution is Not Televised》 at Arko

Museum of Art, the series has been transformed four times, moving from the

Seoul Museum of Art (Song of Yemeni Refugees) to Gyodongdo (Gyodong

Island Soundscape), before concluding with Lullabies of

Multi-cultural Family. In the case of Song of Yemeni

Refugees, the tranquil surroundings of the museum were juxtaposed

with the songs of their homeland that remain in the refugees’ memories, while

in Gyodong Island Soundscape the sounds of the

South Korean/DPRK propaganda broadcast collided with the frequencies of the

beautiful landscape of Gyodong Island, creating a historical beat phenomenon.18

Which

is more “real”: the landscape we see or the sounds we hear? Kwon’s sound works

consistently ask this question without privileging one or the other. The series

continued in 2021 with 《Neverland Soundland:

Byungjun Kwon—A Sound Walk》 at the Children’s

Gallery of the Busan Museum of Art, where, as in this exhibition, viewers and

audience members wearing headphones could hear lullabies sung in the languages

of Vietnam, China, Russia, Uzbekistan, and the Philippines. Anyone from these

countries would have felt at home, but the question here is more about whether

a lullaby sung in a language one cannot understand could “work” in an exotic

landscape that is foreign to him or her.

The

question of whether this characteristic of the work, in which images and sounds

“bypass” each other and “drift” away from each other through a series of

machines, including the headphones, is fully realized in the exhibition, is

unfortunately difficult to answer in the affirmative. The auditory sensation of

listening through headphones may have remained intact, but the heterogeneity

created by the objects in the previous works in their dissonance with reality

or natural space—or “objection,” as I will discuss later—seemed to function as

“art” in the usual sense when confined to the dark ivory space of a museum

gallery. Doesn’t it justify the robot-focused exhibition space and the

audience’s somewhat biased reaction to it?

Light Looking After Darkness

For

the time being, let me put aside this question, which we will return to

shortly, and focus on Kwon’s robots. Despite their deceptive simplicity, they

have some interesting features to ponder. The most impressive is their heads.

It is familiar in Korea as a device for lighting, often called a “lantern” or

“flash light.” The problem is that it is not attached to the robot’s head, but

forms the head itself. Put differently, in these robots, the light replaces the

face or brain, and there seems to be no function for it other than literal

“lighting” or illumination.

This

means that the robot’s movements, or “behavior” itself, is not “automatic.” It

doesn’t have a brain or computer to calculate and determine its movements. The

fact that its behavior is not autonomous suggests that it lacks autonomy, which

means that it is dependent rather than independent. Then on what are they

dependent? Primarily people. They are slow and clunky rather than fast and

exquisite, but even their clunky movements are the product of the care of the

human drivers who reside in the exhibition center. As human-dependent machines,

Kwon’s robots are not fully automatic, but dependent.

These human-dependent

machines usually play the role of “tool” or “means.” A car takes us where we

want to go, a printer prints the documents we need. But what purpose do Kwon’s

human-dependent machines serve? This is also a question of what kind of “tools”

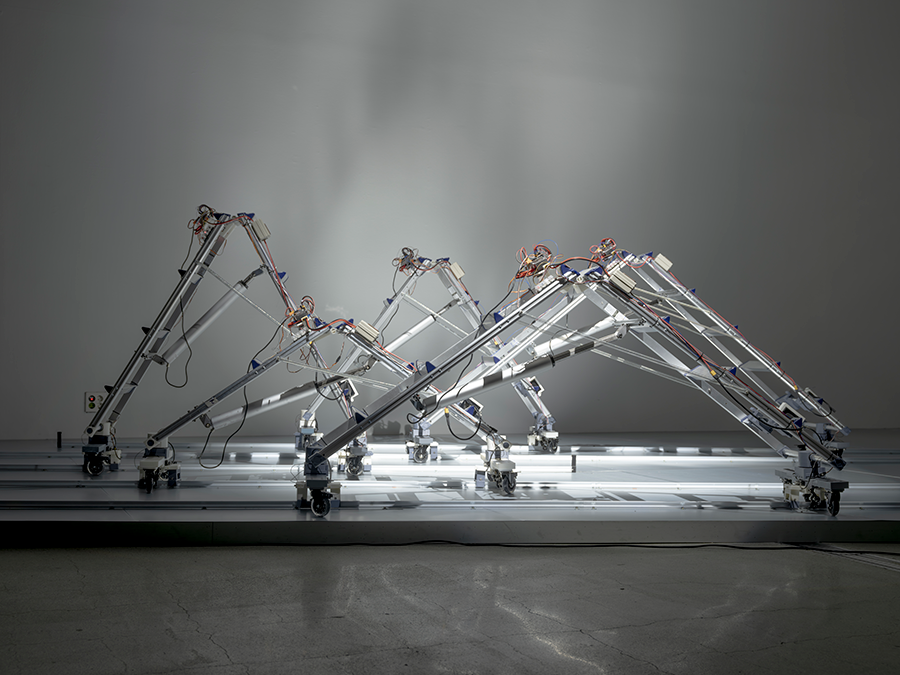

they are, and it’s not easy to answer. The Dancing Ladders,

for example, operate in a way that ignores the raison d’être of ladders,

helping someone to climb to higher heights. They appear to be going forward,

but in fact they are just going back and forth on a set track or going around a

circular track. In this sense, their normal operation is already

malfunctioning, and they are “useless.” This suggests that they may not be

“tools.” Let’s recall that they are not fully “autonomous” but “dependent,” and

that they do not have a computer or a brain. This question is then posed not to

themselves but to a human being, in this case, the artist Byungjun Kwon. What

makes him operate these useless machines? Why did he create them in the first

place? Neither autonomous nor tools, what is their “raison d’être”?

It

is at this point that we must recall that their heads are “illuminating

devices.” Again, their head is merely a device for illumination. What does it

illuminate? According to Kwon, they illuminate other robots. He calls them

“half beings” for they are “one-armed,” and ultimately, through illumination,

they become “complete” as two-armed beings. At this point, many readings

usually jump to a concern for “minorities.” What is truly interesting here,

however, is the fact that the perfection in question is achieved only in

“shadow.” They now literally “look perfect.” Does this mean that their

perfection is not real? Maybe. But more importantly, it is ironic that the

ultimate goal of robots in substance is to create “perfect shadows.”

They don’t

“merge” like, say, Transformers. Then, no matter how perfect they are, aren’t

they nothing but shadows, not the “real thing” after all? This counter-question

makes sense, but it only does as long as one fails to consider the self-evident

fact that a lantern is usually considered an item to prepare for some kind of

emergency. The emergency in question, as you may have noticed, occurs usually

at night rather than during the day, especially when the lights that make human

life possible are not properly functioning. As emergency items, lanterns are

used to dispel the darkness. Kwon’s lantern, however, is used to create shadows

rather than dispel darkness. In other words, it turns his general “raison

d’être” upside down. How about calling it “light looking after darkness”?

The Situationist Future

This

leads us to another related question: what is light and darkness to a non-human

robot? Just as the phrase “your face looks dark today” is not a compliment,

“light and darkness” is a conceptual pair that implies the opposing values of

positive and negative. As a matter of fact, Kwon provides a somewhat negative

answer to a comment that light and darkness coexist in his work. Rather, he

confessed, the robots in his work are the product of his own failed attempts to

create some form of community, exhausted from his relationships with people.19 Again,

it’s not that I can’t understand the desire to label his robots as “minorities”

here. However, Kwon’s work facillitates prudence rather than impatience.

In

this light. his latest work From Cheongju to Kyiv (2022)

must be scrutinized in detail. As the title suggests, the work is set against

the backdrop of the war in Ukraine following the Russian invasion. At a time

when interest in foreign wars has all but evaporated, the artist confessed to

feeling that such indifference is not unlike the indifference prevalent in

Korean society itself. It was in this context that he decided to collect the

sounds of construction sites, where the crunching of wood and roaring of

machinery have become commonplace, instead of the direct sounds of war.

As the

headphone-wearing viewer approaches a building with lots of windows and glass,

the sound of glass shattering and spilling out is mapped, or glass on the floor

breaking in time with their steps. These sounds, like being drenched when

walking under a water tank, are of course virtual. Still, this virtuality

should not be mistaken for mere imagination or a matter of “empathy” for

Ukrainians suffering from war.

More

subtly and crucially, it is worth noting that the sounds in question are

detached from both the actual places of Cheongju and Kyiv. The glass in the

storage building of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in

Cheongju is not broken, the water tank is far from leaking, and the sounds do

not simulate the actual situation in Kyiv. Does this mean that we can only

estimate the disaster in Kyiv through the hypothetical disaster in Cheongju?

Yet this presumption begs a question: can people in other parts of Korea, such

as Seoul, Busan, or Jeju, immediately relate to a hypothetical disaster in

Cheongju?

Just because we are Korean, do we empathize with disasters in

different cities and regions? Or rather, has the situationist’s “detour” and

“drift” not already been accomplished in a paradoxical sense? What if Debord’s

friend, who flipped through a map of London and followed the directions to the

Harz region of Germany, has been replaced by a Tesla shareholder who flipped

through a real estate map of New York or Berlin from Seoul? Are we truly living

in community, or has it already been shattered into pieces?

Heterotopia and Psychogeography

The

French filmmaker Robert Bresson once distinguished between conventional cinema,

or “cinema,” and what he called “cinématographe,” writing that in the latter “a

sound should never come to the rescue of a picture, and a picture should never

come to the rescue of a sound.20 It should be emphasized in

this sense that Kwon’s entire exhibition (mal)operates within this separation

between image and sound. The numerous robots that catch the viewer’s eye

operate in strict separation from the series Forest of Subtle

Truth (2017–19), which is responsible for the axis of sound. The

ceiling-suspended Windbell and Landscape (2012)

only further emphasizes this disjunction.

His

previous work, Self-sounding Town Resonant Village

(2019), is perhaps the most effective at allaying any misgivings this

separation might suggest. The artist’s specially designed headphones are

designed to mix one’s own sound with the sound of the other depending on the

physical distance. And the audience is invited to exchange sounds by bowing

their heads in acknowledgment. Considering that the headphones serve to

separate the individual from others rather than fuse them together, this is

quite impressive. Nonetheless, the work no less presents the self-evident irony

that this beautiful resonance is achieved solely through the medium of

headphones. This point is not to be missed.

In

retrospect, it wasn’t until 2017 that he began using headphones as a major

element of his work. The exhibition at the Arko Museum was organized around

sound, and with more than 10 teams working together, there was a problem. For

the gaseous, wispy nature of sound implied that each sound leaked across the

boundaries of the space and interfered with the others. While the original idea

was to circumvent this difficulty, the function and implications of headphones

in Kwon’s works would later become more and more prominent. In fact, poet and

architect Sungho Ham, in an impressive essay on Kwon’s oeuvre, points out that

“Kwon’s spaces can be called “non-spatial specificity” as they are not fixed in

any particular location,” before concluding that “[t]he sound of the headset

that erases the physical location is the most important aspect of Byungjun

Kwon’s work.”21

This assessment is intriguing, but it also

raises questions. Aren’t all headphones de-locating and re-locating? Where do

the people laughing and talking loudly while wearing Bluetooth earphones on the

subway or street actually exist? Kwon’s headphones’ unique location recognition

function is interesting in this regard. He uses RTK (Real Time Kinematics)

technology rather than the GPS we are used to, and this allows him to operate

what we might call “heterotopian sound art.” As you may recall, the

characteristic Foucault called “most essential to heterotopias” is that they

are “an objection to all other spaces.”22 In this sense, Kwon’s

headphones are distinguished from both the way the sound installed in a

particular place works when the viewer approaches it, and the way the viewer is

freed from the place through the headphones. Kwon’s headphones are a way of

ensuring the autonomy of the individual viewer as they move from place to

place, but also activating sounds that are not inherent to a particular place,

but are differentiated from it and “contest” it.

This

“dissent” also extended to vast physical space. We will have a

serious night” by Ghost Theater (2021/2022), a performance work

that took place in the Namsan Hanok Village and Hongdong Reservoir in

Hongseong. Operating with a radius of 2–3 kilometers, rather than in the

gallery space, which is usually only a few tens of meters, this performance work

amounts to a full-fledged evocation of what the Situationists called

“psychogeography.” The artist released all sorts of sloppy robots, which loosely

filled the main exhibition space of MMCA, into the local neighborhood. As

Sungho Ham points out, they all looked like “cheap artificial

humans”—“one-armed, oneeyed, drunkards,” as he puts it—and one could trace them

all the way back to his earlier work, Burning Eyes of Lonely

Wanderer (2011). As the title—a riff on the lyrics of the theme

song—suggests, the Japanese anime Galaxy Express 999, which

Kwon used as his main reference point, is itself a story about an android in

search of eternal happiness.

In the Beginning was a Medium/Machine

Here

we get to confront the fact anew that Kwon has always been working with

machines or mechanical things. One that comes to mind is A Small

One to Have All (2010). For this performance, which Kwon

described as his “first full-scale solo performance,” he prepared the following

artist’s statement

I

would like to talk about why a person who experiments with new gestures and

performance possibilities offered by a new instrument, and who finds more joy

in playing an instrument on stage with someone and communicating with music,

cannot help but stand on stage with a machine.

Why

was the machine indispensable to Kwon? Why did he want to talk about “why he

cannot help but stand on stage with a machine”? First, as discussed above, it

is worth recalling that Kwon was a musician who worked in a wide range of

genres, from experimental punk rock to minimal house music. Before he became

active in the art scene, he was active in the Korean pop music scene, appearing

on public radio, and machines were integral to both his performance and his

work. Of course, one might counter that there must have been “unplugged music.”

Still, as an extension of the “authentic a cappella music” discussed in the

introduction, this dissent cannot escape the irony of the question: “Does a

recorded unplugged performance remain analog?”23 In a world

where the global music industry has been increasingly reorganized around

streaming service, the status and implications of the listening experience that

accompanies a recording, even if it is played on vinyl, are given relative to

its relationship to the “digital infrastructure.” The naïve attempt at neatly

distinguishing between “digital” and “analog” and “natural” and “artificial”

needs to be further scrutinized as it is directly related to the implications

that Kwon’s work has been (mal) operating in detail.

Let’s

consider Windbell and Landscape (2012), which was

placed in the air in front of the viewers entering the exhibition. This work

utilizes the Pyungyeong, or Chinese lithophone, a traditional instrument with

16 notes. Not only is it remotely controlled, however, the sound itself is electrically

modulated. The source is clearly analog, but the sound it produces is not. We

must not be lazy enough to think of it instead as a simple synthesis of analog

and digital. While Glass sought to transform classical music intrinsically and

structurally through mechanically amplified or modulated rock sounds and simple

bass lines, Kwon, as we have seen, allows image and sound, digital and analog,

human and non-human, to “bypass” each other and “drift” away from each other

through mechanical and electronic means.

For

example, the main difference between most of the machines in the main

exhibition hall with their “lantern” heads and the “six mannequins” in the

right corner of the exhibition revolves around their heads and faces. The

latter, with its scaled-down full-body mannequins and a normal-sized mannequin

head, is a “humanoid” that iconographically immitates the human form. Of

course, you can find a head on the former. However, it is no different than,

say, identifying an insect in tersm of “head-thorax-belly” or mistaking the

rounded bulge of an octopus’s body, which is actually an abdomen, for a human

head.24 This constitutes an important marker for the head, or

more precisely, the face, is usually perceived as the most important plane of

the human “interface.”

Recall the so-called “uncanny valley” phenomenon or the

sci-fi movie Arrival, where aliens pay a sudden visit to Earth. In fact, one of

Kwon’s earliest works, InterFace (2010),

radically questions the identity of the face, or more precisely, the relationship

between the face and (vocal) sound: seven men and women (the “dirty sound

orchestra”) with magnetic sensors and magnets attached to their eyebrows and

cheeks make ridiculous facial expressions under the direction of a conductor,

while the sounds the audience hears are more like frogs, toads, or birds,

electronically modulated. The “ridiculousness” of this work is not unrelated to

the gap between the face and the voice, which is modulated by a machine.25

Relevant

here is his earlier performance work, This is Me (2013).

It is a representative example of his overall concern with the elements of the

(non-human) face as well as the (vocal) sound, in the sense that it

simultaneously engages with the elements of the (non-human) face, a concern

that extends to this exhibition. The performance begins with a whistle from the

artist seated in a chair, who has the camera read a drawing of a face on paper,

which is then recognized by a facial recognition program as the basis for

mapping the face. His face is then projected onto a canvas of white powder

coating, onto which the faces of celebrities such as Nam June Paik and George

Bush, Marilyn Monroe and Kim Gu—Former Head of State of the Provisional

Government of the Republic of Korea—are projected in real time on a large screen

behind him.

On the one hand, the performance recallswell-known projection works

by Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko, who said to Kwon in person that “We are

all strangers.” On the other hand, it embodies, separately and together, the

concept of “per/sona,” which I have elsewhere characterized as the “originary

gap” between image and sound, face and voice.26 In what sense?

In the fundamental sense that each of us is defined by this gap and

heterogeneity prior to our relationship to the other. This is also true of the

behavior of robots that appear to cross wooden bridges, sit and stand up, or

meditate on their own. In the paradoxical sense that, unless they are

autonomous beings, as we have seen, all of these behaviors would literally

appear to us, humans as such.

Outro

At

long last, we are left with the work in the right corner of the exhibition. Due

to the spatial arrangement, most viewers are supposed to see it after viewing

the works in the main exhibition hall. Akin to the abstract of a poetic essay,

it serves to summarize the exhibition, as well as to summarily recall his

previous works. The first thing we notice upon entering the space is a series

of mannequins. Above them is a giant hand manipulating them like puppets. The

format is reminiscent of Russian dolls, with a doll inside a doll and another

doll inside another doll.

The face of another mannequin watches this spectacle

with its back to us, and we, as humans, look back at it. In other words, there

are four layers. But that’s not all. In addition to the docents who are

supposed to protect the work in the exhibition hall, we are constantly exposed

to the gaze of CCTV cameras mounted on the ceiling. Of course, they are not

part of Kwon’s work. However, this inference itself is a product of the

meta-gaze that his work triggers. To be sure, this line of reasoning does not

go on indefinitely. This is because the end of the line of reasoning, or

purpose and use, is posited.

The

purpose of the exhibition camera seems self-evident. All that remains is the

mannequins and us looking at the hands that control them. A strict

cyberneticsist might recall what von Forrester called the “cybernetics of

cybernetics,” the axiom that “that is, we have to observe our own observing,

and ultimately account for our own accounting”27 In this sense,

there is no difference between mannequins and humans. Would Kwon follow this

stance, however? At the very least, we have followed a similar line of inquiry.

We’ve found that Kwon’s imperfect robots with lantern heads, neither fully

autonomous nor fully instrumental, illuminate each other, and in doing so,

create “perfect shadows” rather than dispelling darkness. If we can call it a

purpose, “light looking after darkness” is arguably their “raison d’être.” Is

this light or darkness for us? Is it okay to follow this?

The problem is that

we define “Aufklärung/Enlightenment” and “Enleuchtung/Illumination” as what

literally dispels darkness and awakens us from folly. This means that Kwon’s

robots that “fail” to fulfill the role of the ladder may be at odds with the

Enlightenment program, which promotes growth and contributes to improvement.

This is again emphasized by the fact that their failures are not accidental,

but are programmed to be “repeated.”

Take,

for instance, Samuel Beckett’s famous quote, “Fail Better.” The chronic habit

of still treating this as a “literary rhetoric” of the old, healthy common

sense of “I’ve done better than last year, last month, yesterday, so I’m on

target” does nothing to capture the essence of this exhibition or Kwon’s

oeuvre. Rather, the “failure” that Beckett evokes refers to a yet-to-be-arrived

opportunity to question the very criteria that distinguish “success” and

“failure,” and to seize the capacity to radically redefine its own

self-evidence.

In the radical sense of forcing a given value judgment to

redefine itself, what matters is thus not the best, but “the worst,” and the

more delicate splitting and pushing of the latter. As in the paragraph below,

which Beckett himself deemed almost untranslatable, the hair-splitting bundle

of sentences below, like a single strand of hair, turns the idiom “For lack of

a better word” upside down, so that it reads more accurately as “For want of

worser worst [options] than [this].” Less best. No. Naught best. Best worse.

No. Not best worse. Naught not best worse.

Less

best worse. No. Least. Least best worst. Least never to be naught. Never to

naught be brought. Never by naught be nulled. Unnullable least. Say that best

worst. With leastening words say least best worst. For want of worser worst.

Unlessenable least best worse.28

Bergson’s

assertion that laughter is a kind of “warning” to the flexible “élan vital” to

break free from mechanical rigidity is well known.29 With all

due respect to him, the repeated “mechanical failures” of Kwon’s robots are

more like “exemplary failures” in this paradoxical sense. If Kwon’s “light that

takes care of darkness” can be a guide for us, it is not because there is no

light in our era. Rather, it is because it makes failure and darkness utterly

colorful in an age that seems darker than ever before, born of the abundance of

lights competing to blind us. His call for “expanded music”—“robots are my

instruments, and the process of expanding music and exploring movement can be

considered a performance”30—should be listened to more carefully in

this precise sense.

1

For a more detailed discussion of this point, see Yung Bin Kwak, “Replicants,

Holograms, and the Voice (or Sound) of AI,” in Reading Blade Runner in

Depth (Seoul: Psyche’s Forest, 2021), 183–204.

2

Most of the media coverage regarding Kwon’s winning of the Korea Artist Prize

were predominnantly fixated on “robots.” “’Robot Artist’ Kwon Byungjun Wins

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art ‘Korea Artist Prize’

2023’,” SBS, February 8, 2024; “Robot Performance Kwon Byungjun Receives

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art ‘Korea Artist Prize’,” The

Korea Times, February 8, 2024; “Robot Synthesis Theater Dancing in the

Exhibition Hall…”Drawing the Future of Living with Strangers,” Munhwa Ilbo,

February 14, 2024; “A Human Face on a Steel Pipe Leg… A Successor to Nam June

Paik’s ‘Robot K’,” Hankyoreh, March 21, 2024; “Robot K’s ‘Korea Artist

Prize’ Exhibition: Kwon Byungjun’s ‘Korea Artist Prize’

Exhibition,” Hankyoreh, March 21, 2024.

3

Philip Glass, Words without Music: A Memoir (New York: Liveright

Publishing Company, 2015), 229.

4

“I couldn’t make out what they were singing… If I had an axe, I would have cut

the cables [connecting the guitar and speakers to the power source].” Brad

Tolinski and Alan Di Perna, Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style,

Sound, & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, foreword by Carlos Santana (New

York: Doubleday, 2016). I consulted the Korean translation, The Revolution

of the Loud Bang: 100 Years of Popular Music Through the Eyes of the Electric

Guitar, translated by Ho-Yeon Chang (Seoul: Music Tree, 2019), 258. The

live footage in question is captured in The Other Side of the

Mirror (2007), a documentary about Dylan’s three-year run of Newport

Festival performances from 1963–65, which is also available on YouTube.

5

Noting that the decision to use an electric guitar was only made the day before

the show, Wald does not argue that Dylan consciously planned everything. Still,

in contradistinction to his previous way of chatting with the audience in a

cheerful and friendly manner, his demeanor on the night, playing only three

songs before leaving the stage without comment, could be seen as a stark

response to the audience, who were “looking for answers” to the turbulent times

from the “hero of folk music. “50 Years Ago, Bob Dylan Electrified A Decade

With One Concert,” NPR, July 25, 2015; Elijah Wald, Dylan Goes

Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the

Sixties (New York: Dey Street Books, 2015). The performance, often

characterized as “punk folk,” is reminiscent of the September 1997 incident in

which Kwon, then the vocalist of the punk rock band Pipelongstocking, stuck out

his middle finger during the live performance. The incident, which resulted in

the band’s suspension from the show and a massive public outcry, went beyond

his growing alienation from the rock music form and industry. It was perhaps an

“innervation” in advance of a historical course that would be formalized a few

months later with the IMF crisis. This notion, which Walter Benjamin sought to

forge in its relationship with technological media, is grounded in Freud’s idea

of the transfer of energy, or translation of often overwhelming and

incompatible mental excitement into something somatic. Benjamin focused on film

and photography, but this discussion could be extended more effectively to the

relationship with music. Cf. Matthew Charles, “Secret Signals from Another

World: Walter Benjamin’s Theory of Innervation,” New German

Critique 45, no. 3 (2018): 39–72; Miriam Hansen, Cinema and

Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W.

Adorno (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 132–147.

6 Words

without Music, 240.

7 Words

without Music, 230.

8 Words

without Music, 240.

9

His real name was Rabindra Shankar Chowdhury (1920–2012). A master of the

sitar, a traditional Indian instrument, he had a profound influence on Western

popular and classical music, especially after World War II, including Beatles

member George Harrison and violinist Yehudi Menuhin, to name just a few.

10 Words

without Music, 229.

11

An accomplished pianist and author of The Classical Style: The Musical

Language of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, a modern classic recently translated

into Korean, renowned musicologist Charles Rosen summarized Cage and Glass’s

works as nothing more than a “neutral musical ‘surface’” overlaid with a few

“classical formulas” that stripped classical music’s scales of their original

meaning and function. It’s an “interesting“ moment but ultimately an

“impoverished music,” he dismisses. Charles Rosen and Catherine

Temerson, The Joy of Playing, the Joy of Thinking: Conversations about Art

and Performance (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 57–58.

12

Friedrich Kittler, Grammophon, Film, Typewriter (Berlin: Brinkmann

& Bose Verlag, 1986), 107; Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film,

Typewriter, trans. Geoff Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 1997), 111.

13

The phrase “to reproduce as loudly as possible, but very cleanly, without

distortion” belongs to Munkachi. Quoted in David Allen Chapman, “Collaboration

Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York,

1966–1976,” University of Washington in St. Louis, PhD thesis (2013), 92.

Glass’s fascination with “distortion-free roar” also provides an interesting

point of contact when compared to the later tendency of hard rock and heavy

metal, whose mechanical sound textures and enormous volume serve to reinforce

the myth that “authentic rock and roll” is an “inherently masculine form of

music” Cf. Christopher R. Martin, “The Naturalized Gender Order Of Rock and

Roll,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 19, no. 1 (Spring 1995), 71;

Simon Frith and Angela McRobbie, “Rock and Sexuality,” in S. Frith and A.

Goodwin (eds.), On Record (New York: Pantheon, 1990), 371–389.

14

Sound art researcher Caleb Kelly considers 1969 to be a watershed year in which

sound art in North America and Europe was foregrounded through galleries,

citing the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition Anti-Illusion:

Procedures/ Materials (May 19–7.6, 1969), in which Glass and Steve Reich were

key members, as an exemplary example. Caleb Kelly, Gallery Sound, New

York: Bloomsbury, 2017, esp. 111–123.

15

“Kwon Byungjun | Artist Interview | MMCA Cheongju Project 2022: Urban

Resonance,” MMCA, October 7, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v

=7jVf_gTwvCc. Accessed February 7, 2024.

16

Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital

Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 37.

17

“Sex pistols, the invention of punk,” France 24 April 16, 2010;

Fergal Kinney, “Did Punk Start as a Situationist Stunt?,” Jacobin, May 3,

2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/05/did

-punk-start-as-a-situationist-stunt; Uncreative Writing, 39.

18

Beat phenomenon revolves around a pulsation that occurs when two waves with

slightly different frequencies combine.

19

“Kwon Byungjun | Artist Interview | MMCA Cheongju Project 2022: Urban

Resonance,” MMCA, October 7, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=7jVf_gTwvCc.

20

“Un son ne doit jamais venir au secours d’une image, ni une image au secours

d’un son.” Robert Bresson, Notes sur la cinématographie (Paris:

Gallimard, 1975), 63; Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematographer, trans.

Jonathan Griffin. With an Introduction by. J. M. G. Le Clézio (New York: Green

Integer, 1997), 62. This sentence, taken from my catalogue essay to the solo

exhibition of Joon Kim, an important contemporary sound artist, is arguably the

core axiom of sound art. Along with Kim Seo-ryang, he was one of the two sound

artists who participated in the 2022 exhibition in Cheongju, where Kwon

presented From Cheongju to Kyiv. There are many other interesting

contemporary Korean sound artists, such as Youngsup Kim, who studied under

Christina Kubisch, one of the first generation of German sound artists; Young

Eun Kim, who won the Song Eun Art Prize for sound art before Joon Kim; and Ryu

Han-gil who are preoccupied with the relationship between noise and music, and

Seo Sohyung whose work has probed the relationship between silence and music.

Due to time and space limitations, an extensive discussion of Kwon’s

relationship to them and the contemporary sound art landscape will have to wait

for another time. Some clues can be found in the following. Yung Bin Kwak,

“Per/sona after Cinema, or Sound-based Art Beyond the Logic of Mask and

Revelation: On Joon Kim’s Artistic Oeuvre,” in Joon Kim: Tempest JOON KIM:

TEMPEST, exh. cat. (Seoul: Song Eun, 2022), 32–38; Yung Bin Kwak, “(Not)

Showing and (Not) Hearing the Asymmetry of Sound and Image: On Seo So Hyung’s

Artistic Oeuvre” (2022).

21

Sungho Ham, “Beyond Existence— Unknown Places and Nameless Times: Focusing on

‘We will have a serious night’ by Ghost Theater— Hongdong Reservoir, 2022,”

https:// drive.google.com/file/d/1gPQGVcme V0dfIDagsJLhQLiYTopFtNX4/view.

22

Michel Foucault, Heterotopia, translated by Sang-gil Lee (Seoul, Korea:

Munhwa Geosungsa, 2014), 24.

23

On this, see Benjamin Peters, “Digital” in Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary

of Information Society and Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

2016), esp. 101.

24

The head of an octopus is the small part that connects the body to the legs,

and is actually between the legs and the belly.

25

“Inter-FACE by Byungjun Kwon [STEIM] & The Dirty Electronics Ensemble,”

PACE Studio 1, DeMontfort University, Leicester, 20th Jan 2010

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v =SrNjNlaPg48

26

Yung Bin Kwak, “The Compulsion to Repeat History as Per/sona: Im Heungsoon and

Audio-Visual Image,” The Korean Journal of Arts Studies 21 (2018):

197–222.

27

Heinz von Foerster, “Cybernetics of Cybernetics,” in Understanding

Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition (New York: Springer,

2003), 285–286.

28

Samuel Beckett, Nohow On: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, and Worstward

Ho (London: John Calder, 1989), 118.

29

Henri Bergson, Le rire.: Essai sur la signification du

comique (Paris: Éditions Alcan, 1900/1924).

30

“Robot Synthesis Theater Dancing in the Exhibition Hall… Drawing the Future of

Living with Strangers” [in Korean], Munhwa Ilbo, February 14, 2024.