Unwavering and Decisive

His

works are romantic. It may be because he is the most romantic person in the

world. I have witnessed the irreplaceable traces he has inscribed upon the

world of art, music, popular culture, and the underground scene over a long

period of time, all without losing the heart of an artist. The artist’s heart

that I have seen through him is one that is unwavering and decisive unshaken by

cynicism, and above all a spirit of perseverance, which does not stop looking

at the world as if encountering it for the first time, even in the face of

inevitable failure. His works are, in this way, romantic and humane. The

awkward words used to describe him will always remain of secondary importance.

I feel guilty compressing the earnestness, subtlety, and well-subdued sadness

of his work into the word “romantic,” which is too narrow a term, and yet I

have difficulty explaining it in words other than romantic. The rhetoric of

“romanticism” does not only convey gently heightened emotions. His works also

have a cool and rough side. His exhibitions do not hide safely behind typical

conventions and they say what they want to say without beating around the bush.

The objects and scenes he performs combine somewhat precarious gestures and

actions and reveal their vulnerability without adding or subtracting anything,

rather than creating a beautiful sense of déjà vu all at once.

These sentiments

of precariousness and vulnerability lie at the root of his calling his robots

“cheap cyborgs.” These aspects are not what we usually expect from technology

or machines. He is an engineer who probes how technology for which its perfect

end point has vanished operates as a homogeneous force, disappointing both

futurists and reactionaries alike.

Humans

What

is the source of inspiration behind his “cheap” robot? I am reminded of several

video works that dominated my childhood. In Laputa: Castle in the Sky

(1996), Sita, the main character, taken by an agent of the Empire, witnesses a

mechanical soldier fall from the sky. They both fell to the ground from the

same place. The mechanical soldiers created to replace humans have long

well-equipped arms and shoot explosive beams through a hole in the face.

However, after the human orders are executed, they become like a part of nature

that is weathered or eroded, repeating actions that are close to meaningless.

The new mission discovered by the mechanical soldiers is to lay flowers while

tending to the tomb of the Buddha or spending time with wild animals. The first

emotion that Sita feels upon encountering the mechanical soldier is not hatred

of difference, but compassion for the thing that was destroyed by the fall. The

mechanical soldiers battle against the human army to protect Sita, and despite

the machines’ overwhelming violence, the robots give the impression that they

are closer to humanity than humans. The next scene is of the machine people

from Galaxy Express 999 (1977-1979).

In Matsumoto Leiji’s

(1938-2023) worldview, the desire to become a machine people is an important

motive that runs throughout the entire narrative of the work. This desire is

intensified or frustrated in the conflict between humans and machine people,

and coincidently, fulfilled or overcome with the help of other machine people.

Machine people are hybrid robots that have either a machine transplanted into a

human body, or conversely, a human mind transplanted into a machine. They are

portrayed as beings who transcend humans by gaining a semi-permanent lifespan,

and despite some negative aspects, they are considered to be one of the only

ways for humans to advance their humanity.

Ghost in the Shell

(1995)—directed by Oshii Mamoru (1951- )—in which the main character Kusanagi,

who chose to hybridize with a machine, is crashed into the world of the “Net”

that is different from the past—and before that, Mighty Atom

(1952-1968)—Tezuka Osamu’s (1928-1989) worldview drawn at the intersection of

machines and humans—are part of the same base of popular culture that lie

within the scope of similar ideas. In short, they raise questions about the

pure-blooded nature that humans are born with, and paradoxically, view the

acquisition of more fundamental traits in the process of becoming closer to a

kind of mixture or by-product.

The

idiomatic personification of robots rather than supernatural minds or spirits

is an interesting stance assumed by twentieth century East Asian popular

culture. In contemporary East Asian popular culture, which possesses an

inherent subculture context, robots are not unknown beings from another world,

scientific disasters or the potential for disaster, or harbingers of terrible

end times, but rather something in the vicinity of humanity, or more

specifically, by way of adding or subtracting something out of a human being, a

subject that makes visible what is absent in the mainstream “pure” human being.

One episode of Tezuka Osamu’s monumental work, Phoenix

(1954-1988), questions the humaneness of machine people in comparison to

clones, the most accurate reproduction of human beings. The discovery of

humanity refracted through robots may be a feature that East Asian cosmological

traditions share with later generations. Philosopher of technology Yuk Hui’s

concept of cosmotechnics has been frequently cited in recent discussions. We

are accustomed to accepting new technologies as something that is literally new

or as an unknown innovation, but if humans are, at the level of being, “things”

in a certain state that can be represented as a technological creation or

configuration, the acceptance of technology is ultimately related to the

restoration of order and morality inherent in human beings.

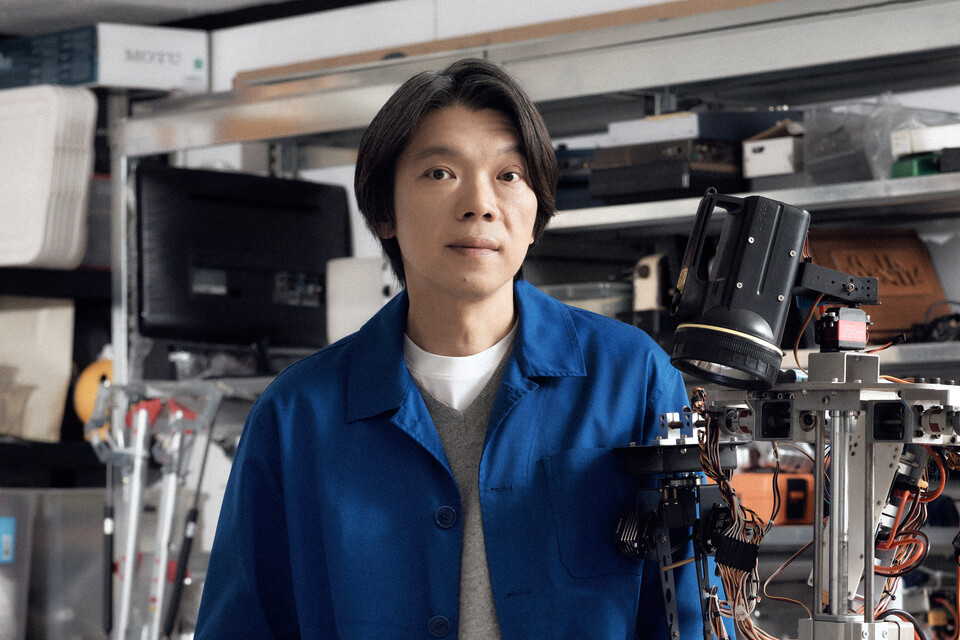

This is consistent

with the meaning of Byungjun Kwon’s robots. Just like his robots in the

cultural context, Yuk Hui’s theory reads like a philosophical subculture.

Although it seems difficult to accept this as a general scientific theory about

technology, the possibility that it can be realized first through art and

culture as an appropriation of the modern technological system, or may have

already been realized, cannot be ruled out. The work that Byungjun Kwon has

retrospectively described as his first solo performance was given a title—Small

Ones to Have All (2010)—that symbolically encapsulates that very possibility

and attitude.

At

some point, he wrote the following about robots. Robots are comrades who had

each other’s backs in the club scene in the 1990s. Robots are strangers,

foreign workers, who urged him to take interest in “non-beings.” Robots are

refugees who have lost their coordinates. Robots are drunks. Robots that are

assembled from miscellaneous hardware and have lost their purpose appear to

have each their own defects. Our comrades went their separate ways and art that

did not cater to capital was forgotten. Strangers are repeatedly deported.

Hometown has become an obsolete word for everyone. Drunks wander in their

dreams and suffer from hangover. For some reason, robots appear to wander like

ghosts unable to take one side or another. His robots operate based on the same

ethics as humans. And the moment they come into conflict with a universally

legitimate promised order (“truth” for Byungjun Kwon) or episteme

(philosophical high culture for Yuk Hui), they embrace and awaken each other’s

malfunction.

Faces

In

This is Me (2013), he uses himself as a medium. This

is Me projects a constantly changing “face image” using a light

projector after painting his face white like an empty projection screen or

canvas. The image of the face overlaid on his face is then displayed again on

the wall behind where he is positioned though a video device. Facing the

blinding light of the mechanical device, he sometimes looked as impassive as a

machine, and sometimes painfully elevated. He appeared to have become the

medium. The issue of identity that This is Me deals with is

something that always returns and is repeated in contemporary art, but through

mechanical recognition procedures, recording, and screening using facial

recognition, mapping, and image generation technology, rather than simply

expressing the confusion felt by an individual artist, his work became a

performance that presented the human face as a device or the representation of

humanity in a hybrid state looked upon as a device.

Although it gives form to a

simple idea, it appears to have been an important opportunity for him to

clarify his position in the field of art. The Byungjun Kwon of Another

Moon Another Life (2014) orchestrates his work more like a neutral

technician. Another Moon, Another Life was released around

the same time as This is Me, and as the title suggests, it

places the “I” at the boundary of the theatrical form and builds up a complex

stage apparatus. As a director and performer, he uses various elements on the

stage and fuses traditional theatrical elements with media technology. He looks

like a foreign substance transplanted onto the stage. And here, as the steam

sprayed by the machine takes the place of the role of the face, the “I”

presents the possibility of a new mechanical face in relationship with the

foreign substance accumulated on stage. It appeared to suggest the emergence of

the robot as a meta-subject for Byungjun Kwon.

Meanwhile,

shortly after returning from the Netherlands, he performed Six

Mannequins (2011). This performance was a collaboration with his

long-time comrade, the musician Dalparan, and as such, it allows us to look

more closely at his present and past as an artist. What is the difference

between mannequins and robots? The mannequins used in Six Mannequins

were limited modifications of ready-made products unlike the robots, which are

closer to handicrafts. However, the fact that they are mass-produced products

stamped out in a factory does not lead directly to the special interest in the

mannequin. Mass production is too common a material condition to determine the

aesthetic uniqueness of a work today, and its plurality does not necessarily drive

an art work into one side or the other, whether good or bad. Compared to

robots, mannequins mirror young, beautiful bodies as the shell of consumption

that adheres closely to the product without any gaps.

It is ironic that the

mannequin, faithful to the eroticism of the body, can look like a dead body or

induce a sense of the grotesque, but in short, it appears to have been a

stopover reached by Byungjun Kwon as a musician while trying to make sound with

foreign substances as an artist. Kwon and Dalparan amplified the otherness that

the mannequin instinctively evokes and imploded it as if by accelerating it,

adding gestures that cannot easily be embodied by a mannequin and overlaying it

with indescribable dissonance and sounds resembling screams. The ruptured

mannequin, having exceeded the product’s threshold, was collected by them as

the wreckage of a familiar sound. At this time, Byungjun Kwon’s experiment was

to theatrically declare the first-person “artist” of Small Ones to

Have All at the furthest distance from himself, while at the same

time disturbing the directness of the word “theatrical.”

On the other hand, in 《Club Golden Flower》 (Alternative Space LOOP,

2018), the robot projected his purposeful body is made to entertain feelings of

sorrow. Like the remains of the mechanical soldier that has crashed to the

ground seen by Sita, the robot is a kind of blank face, pupils where the splintered

remnants of an industry or a commodity have fallen. Without depicting humans

specifically, it evokes the common customs and nostalgia that once belonged to

humans. Where is the place we crashed before we broke into pieces? At this

stage, his robot passes through the database of local popular culture, and

presents a more vernacular aspect than that of the mannequin as a shell for the

human-commodity. Gil’s Doll (2006) and Out of body

Mannequin (2011) can be referenced on that route.

Light and Sound

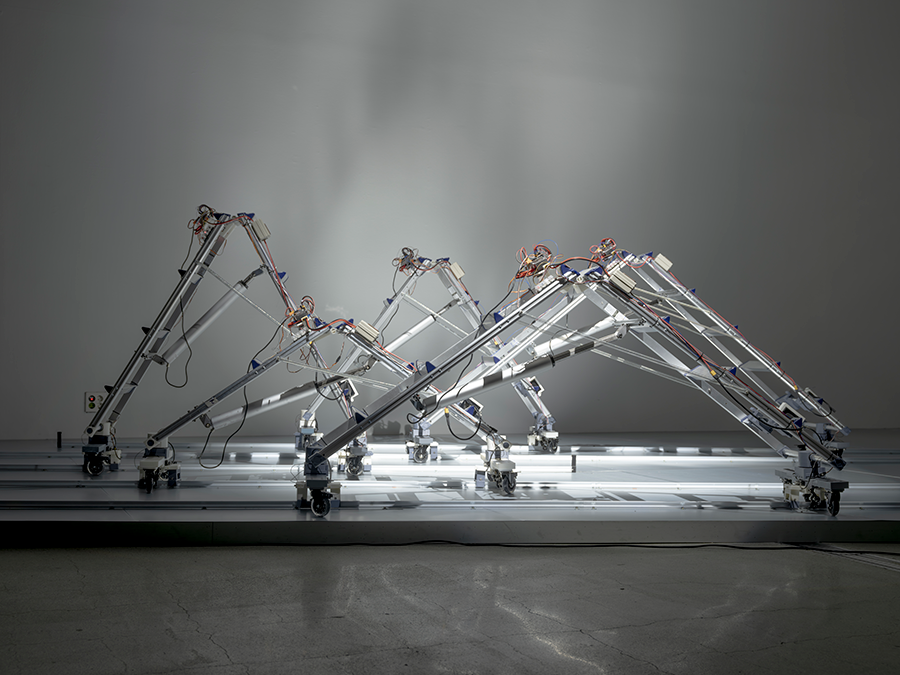

Even though 《Club Golden Flower》 took the form of an art exhibition, his series on robots were

generally closer to a theatrical play with robots on stage. Lyrics of

Cheap Cyborg 2 was selected as an invited work for the opening

commemorative festival at the Daehakro Theater Quad, which introduces

experimental plays, in 2022. As a sound technician and engineer, and as a

member of a rock band that left a radical mark, it is no exaggeration to say

that his work is fundamentally based on performance that borders on the

theatrical.

In his works, the expression “performance,” or more concretely,

“robot comprehensive performance,” or as classified by media specificity,

“robot mechanical theater” have all been used interchangeably. Regardless of

the theoretical approach, he does the work of a screenwriter and director. His

work induces a theatrical experience, offering the feeling of entering a scene

on stage. Coincidently, saying that his work is theatrical does not appear to

be a great compliment in contemporary art. There seems to be an instinctive

fear of theatricality among curators, critics and so-called institutional

experts. Sometimes this fear feels like an inherited defense technique passed

down to some part of contemporary art to protect its genetic specificity from

the characteristics of the same species from which it is derived. Thus, the

“indifference” with which he deals with theatricality ends up making

contemporary art and the museum, its temple, uncomfortable.

Byungjun

Kwon’s most striking theatrical element is the use of shadows. Most of his

robot series create shadows with artificial light. Here, curators and critics

already find themselves at a loss. In so far as the shadow is subordinated to

the object and seen as a passive support, it brings up the memory of classical

philosophy devaluing classical art as an inferior representation. This is

because it is a form of visuality that modern art avoids in that the support is

an obscure illusion and gives rise to a groundless “feeling.” Moreover, the

robot, chosen as the main character in the spotlight, is mistaken for the

personification of an object, causing trouble once again—within the upheaval of

new materialism, the personification of an object will be read as a worn out

symbol of the art of the past.

However, the shadow is not simply a theatrical

element that stirs up a “feeling.” For example, if we pay attention to the fact

that the robot in 《Club Golden

Flower》 is a luminous body with a lantern grafted onto its

face, the robot’s shadow makes visible the connectivity that organizes “the

construct that includes itself, including itself.” Also, artificially enhanced

lighting is an autobiographical symbol of power, self-consciousness, and pain

in that it is the performance industry’s way of objectifying something.

Therefore, the artificial light in his play is the robot’s prosthetic body,

extended like another substance, composing a cluster of mechanical devices.

The

robot in the 《Korea Artist Prize 2023》 repeats the political gesture that overheats the the human world’s

networks, such as the ritual prostration, sambo ilbae (three steps, one bow).

At the same time, however, the robot is broken down by light and the white cube

into the movement of things or machines. What is maximized here is not the

double representation or illusion of space through the mobilization of shadows,

but the strange experience of materialization in which bodies and prosthetic

bodies are mixed and scattered in uniform waves on the wall.

In

his plays, sound is a special indicator. Unlike the experience of seeing or

reading, listening has been regarded as a mysterious and individual experience.

For modern people, the phonetic is the logos that needs to be overcome, and for

ancient people, tone and scale were the forms connecting an indispensable

ontology to the human world. People no longer believe that discerning “good”

sounds is related to verifying the order of the times. In certain respects,

technology and devices have dismantled sound. Today, all hearing becomes a

broken code and inevitably passes through mechanical processes. Conversely, it

means that the mechanical processes must reassemble the sound.

For Byungjun

Kwon, contemporary hearing is an exploration that embraces the power of these

devices. The work of creating sound in a play that traverses space— Gyeongwon

Line Marc (2014)—the work of recording and deciphering the beat

frequency of a bell—Sobbing Bells (2015)—or the work of

using a piano that can no longer be called a piano to intervene in the

cityscape—Song for Taipei (2016)—all include the

characteristic of sound as an indicator, the workings of technology, and

concerns about incorporating performance.

The Forest of History

Collecting

and editing sound came from his personal experience. Witnessing the “third

impact” of ideology on campus in the early 90s, he lost his sense of direction

and relied on sound. There were new deaths everywhere overshadowing the

meltdown and collapse of the harsh old system. The desire for liberation that

flared up in people was a harbinger of freedom that dominated all criteria.

With the standard-bearers of the revolution responding to change faster than

anyone else, the slogans dispersed and only sounds remained. Perhaps the sense

of sound channeled through headphones at the end of an already worn out era was

for him the only surviving sense of history.

In his first presentation of Forest

of Subtle Truth I (2017), this small ember-like sound remained like a

murmur. This sound, which is like the stage whisper by an alienated individual

or the sibilant whisper of history, is transformed into the sound of ideology,

the owner which can no longer be known—Forest of Subtle Truth 3:

Gyodong Island Soundscape (2018)—or the sound of refugees and

migrants—Forest of Subtle Truth 2 (2018, 2019) and Forest

of Subtle Truth 4: Lullabies of Multicultural Families (2019).

Today,

his robots gather in the lights with “some dozing off” and “some coughing from

colds.” Like a scene drawn from the stanza of a poem, they evoke the most

common image of the people, disciplining themselves to be useless, as each in

their own way of being. However, the Forest of Subtle Truth is not just a home

for humanoid robots that metaphorically represent humans, or a tomb-like

resting place secured for them.

In the forest that he has blanketed with sound,

robots and humans are shadows that wander and struggle within their own

channels. How are we to call that history again? Now everyone too easily says

our narrative is over. They say that someone among us changed sides. Is that

enough? If there is nothing more to commemorate, what trace is left in this

place? He seems to want to talk about the stains that are still on us and will

not easily go away. He is as unwavering and decisive as ever. His works are

humane and romantic.