Sound,

noise, and music are not separate concepts; one’s recognition of each shifts

with subjective thought and sense. The world is filled with innumerable sounds,

and noise is always present around us yet remains unnamed as a “being.”

Following Schafer’s question: “What sounds do we want to preserve, encourage,

and multiply?” As a person in the world, Kwon would likely answer: “It differs

for each of us.” Schafer then asks, “How, through art—and especially music—does

humanity create an ideal soundscape for another life: a life of imagination and

spiritual reflection?”5

The answer belongs to viewers and readers. Still, in

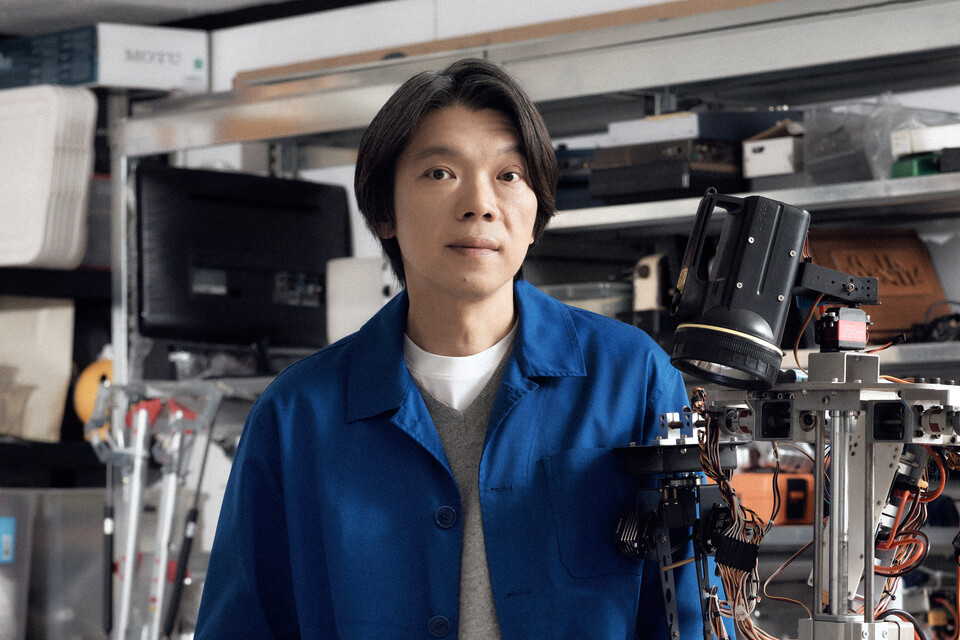

Kwon’s work—as an artist who harmonizes personal sensibility with social

consciousness—we can find one clue, one case. Consider the popular soundscape

of contemporary urban life. Uncontroversially, traffic noise predominates. In a

greened park, in an alley dense with large housing complexes, even in a small

theater in a busy district, the sounds of speed from cars, airplanes, and

trains resound near and far. In the convenient urban life afforded by diverse

infrastructures, soundscapes are nearly standardized, and urbanites suffer a

degree of collective hard-of-hearing amid ceaseless machine hum. How then can

soundscapes, in such an environment, become a way to imagine another life?

Over

the last decade Kwon has developed projects that play recorded or collected

sounds—using, for example, headsets equipped with positioning systems and

ambisonic technologies—in varied forms. This is not an aural re-education

project that, within an indiscriminate and chaotic sound circumstance, asks you

to separate micro sonic elements and savor them as “pleasant.” The semantic

stratum of sound differs from piece to piece, so we cannot generalize; but

drawing on my memories of a few works I have directly experienced and related

documents, a common principle is a “disjunction” between sight and hearing.

Wearing headphones in the usual way, one is separated from the visual reality

before one’s eyes and immersed in an individuated auditory world; unlike the

experience of hearing a sound that corresponds to the visual scene—say, a car

passing on the road ahead—one hears sounds decoupled from the visible

landscape. Kwon then rebinds the headphone-borne sound to the physical space

inside and outside the eyes in a novel way. This parallels how sight and sound

work in cinema: images do not contain sounds; in film, sound, like vision, is

edited and montaged. Kwon does not use video or photographic imagery, and

instead confronts us with real-time, natural space; yet through sound-editing

alone, the image of visible reality is transformed.

From

Cheongju to Kyiv (2022) mapped the soundscape of an imaginary

city in a museum’s outdoor plaza, so that visitors could wander with headphones

and listen. There is no particular relation between Kyiv, the capital of

Ukraine, and Cheongju, a provincial Korean city. Yet Kwon, attentive to the

charged geopolitical climate and the affect of anxiety gripping individuals

after the Russia–Ukraine war broke out, responds to an encompassing museum

brief on cities and sonic perception with a daring theme. Here, too, the

audience encounters the “sounds of tension and anxiety” through headphones as

usual, but he designed a moment in which all listeners simultaneously hear the

same sounds—sirens and airplane noise.

Forest of Subtle Truth (2017–2019)

likewise carries clear social consciousness and subject matter: songs of Yemeni

refugees who arrived in Jeju without authorization; the soundscape of Gyodong

Island near North Korea; lullabies from multicultural families in Hongseong, South

Chungcheong. Kwon goes to meet the people he worries over and confronts events.

The sounds he gathers across the country connect—via headphones in museums and

theaters, studios and classrooms—to anonymous viewers. The site of reception is

largely abstract, but the places he leads us to are not a “bleached here,” but

a “variegated there.” The audience listens to a speechless tale, a song without

representation, a theater that unfolds invisibly. Poet Ham Seongho notes the

“headset sound that erases place” in Kwon’s work,6 but here I wish to

underscore a place-ness over there that appears only through sound, unseen.

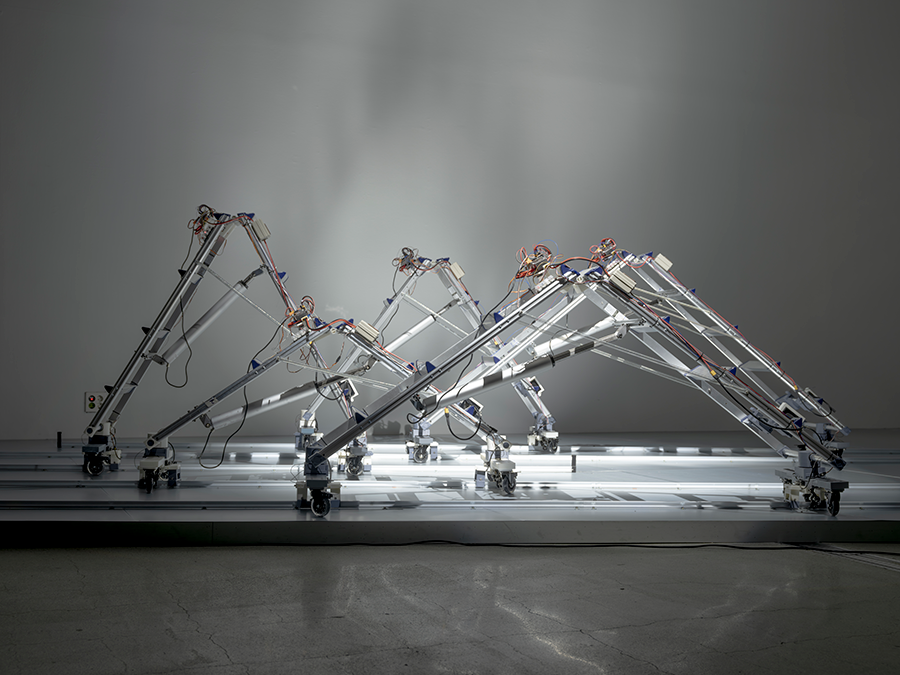

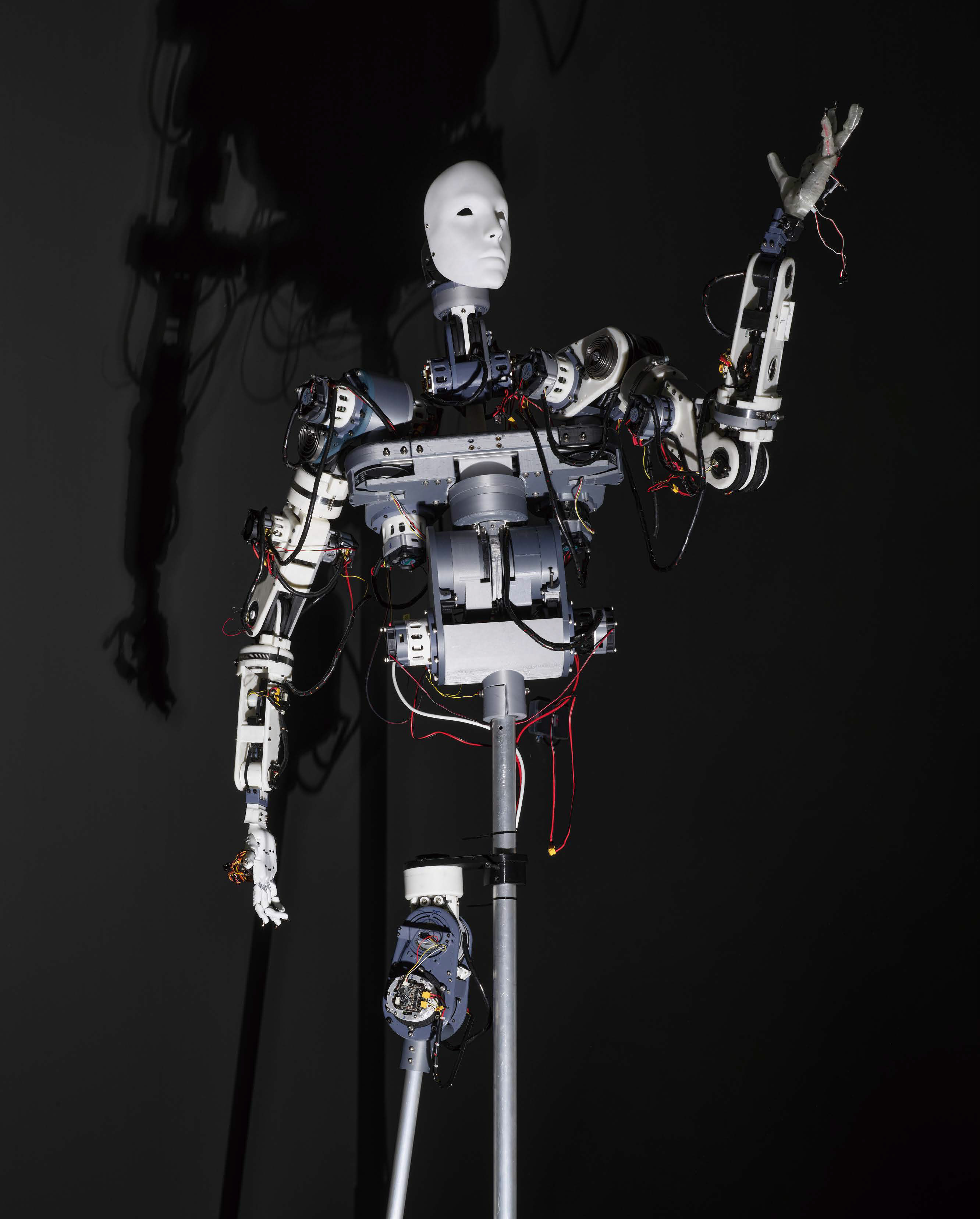

When

Boston Dynamics’ impeccably bipedal

robot executes a tumbling routine with smooth ease,

Kwon’s robots limp along from atop a tripod

or creak on ladder-legs.