1

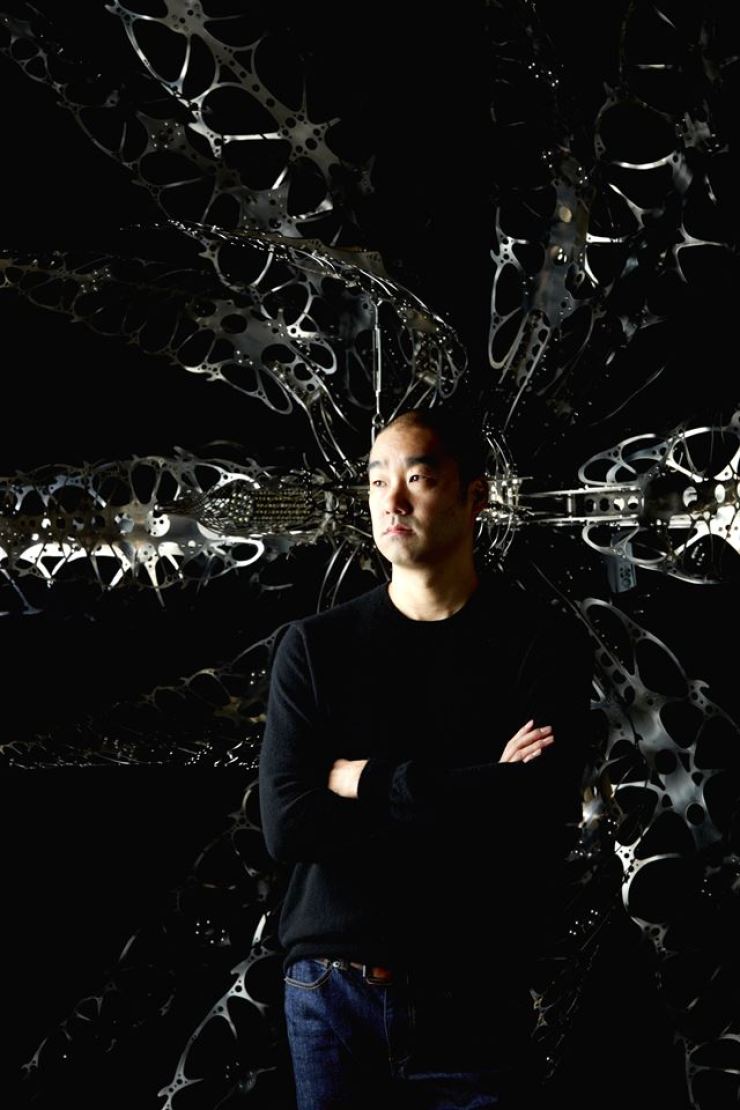

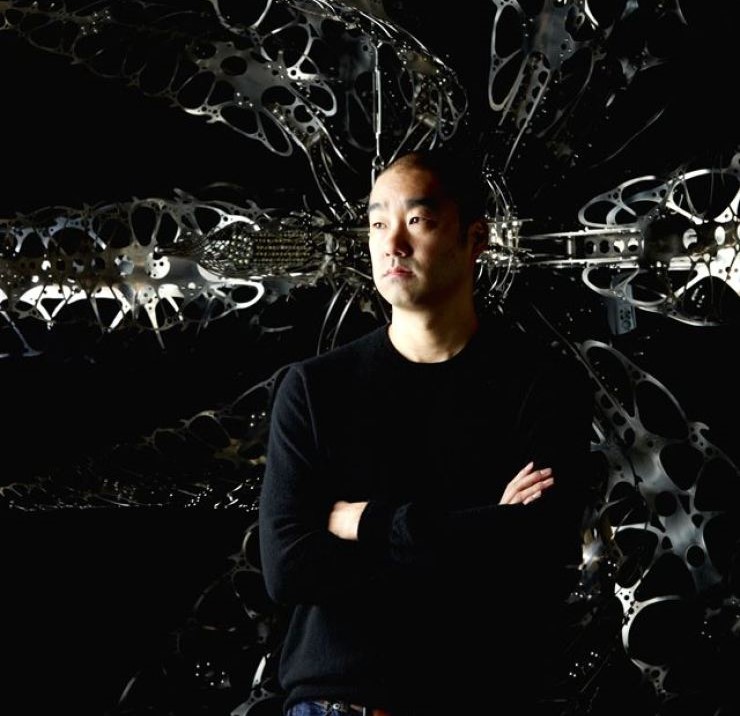

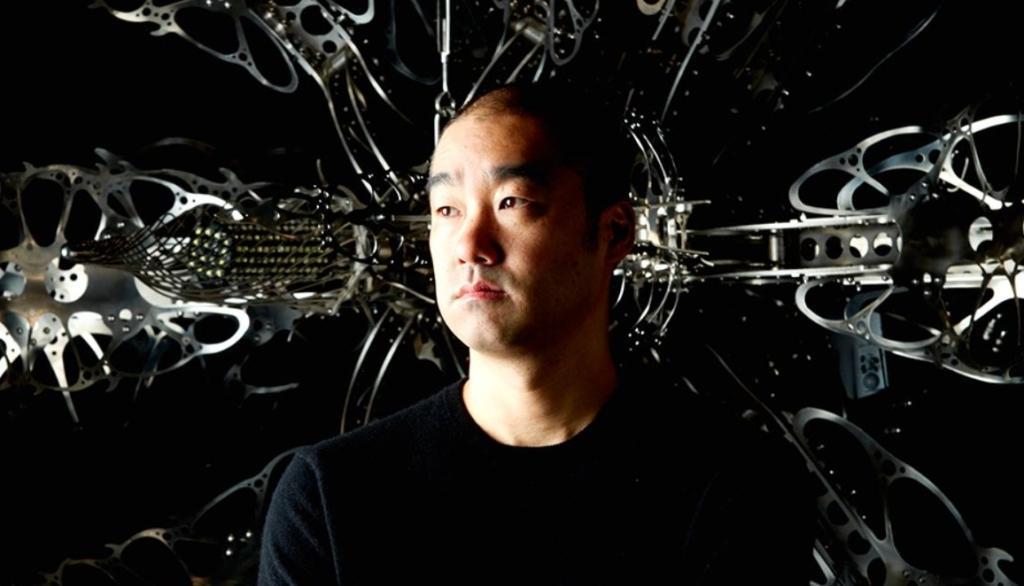

Choe U-Ram is widely known as an artist who creates “anima machines,” or

mechanical life-forms. With kinetic works that showcase imaginative artistry

and an exceptional sense of form, he has drawn attention not only in Korea but

also at leading museums, galleries, and biennials abroad. Since his first solo

exhibition in 1998, his sustained interest in movement has driven a practice

that demonstrates not only formal and technological advances over the past

fifteen years, but also expansion and evolution in content. His 2012 solo

exhibition clearly revealed the broadened spectrum of his work.

While

preparing for his first solo exhibition in Korea in a decade, the artist seems

to have taken time to look back on his practice. Spanning works from drawings

he made at age seven to recent pieces, the show offered a cyclical loop that

returned to the starting point of his art and asked, “What is art to me?” Like

the serpent biting its own tail in the work Ouroboros,

a linear concept of time is dismantled and the past, present, and future

interlock ceaselessly. Found in nearly all civilizations and noted by the

psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, the ouroboros is an ancient religious symbol

that signifies the union of opposites. Choe’s art exists precisely within a

process that seeks harmony and balance—between machine and nature, myth and

science, emotion and reason—just as the circular motion of Ouroboros dissolves

binaries and reveals a state in which opposites are integrated. “Cycle” and

“expansion”: with these two words, we can approach Choe U-Ram’s “here and now.”

2

From childhood, Choe loved science-fiction cartoons and anything that moved. He

often lost track of time drawing, and he was particularly struck by a jewelry

design that reproduced a heartbeat at the exhibition Salvador

Dalí Sculpture he once visited with his mother. But there was

something unusual about his early drawings: even when he drew robots, he did

not focus on embellishing their exterior. Instead, he outlined the forms and

then filled the interior by imagining what lay within. At seven, he drew

mechanical components inside a whale rather than organs. One might say the

meeting of machine and life had already begun.

The

artist’s long-standing imagination of mechanical life-forms is closely tied to

a deep interest in nature. As with countless artists in history, nature is also

Choe’s model for art. Drawn for years to moving things, he seeks to recreate

the awe he feels in nature by animating machines. A frequent viewer of nature

documentaries, Choe says, “Through machines, I wanted to show the beauty of

nature.” He speaks of the reverence he feels when witnessing the vastness of

nature and the tenacious vitality of diverse flora and fauna. Indeed, his works

to date present images in which nature and machine intersect. Through his

imagination, forms of insects, fish, and plants are intricately fused with

engineered mechanical structures, furnished with plausible Latin scientific

names, and accompanied by texts about these life-forms.