Consequently,

each part contains in itself springs whose forces are proportioned to

its needs. Let us consider the details of these springs of the human machine.

Their actions cause all natural, automatic, vital, and animal movements. Does

the body not leap back mechanically in terror when one comes upon an unexpected

precipice? And do the eyelids not close automatically at the threat of a blow?

... Do the lungs not automatically work continually like bellows?

-

La Mettrie, L'Homme Machine, 1748(1)

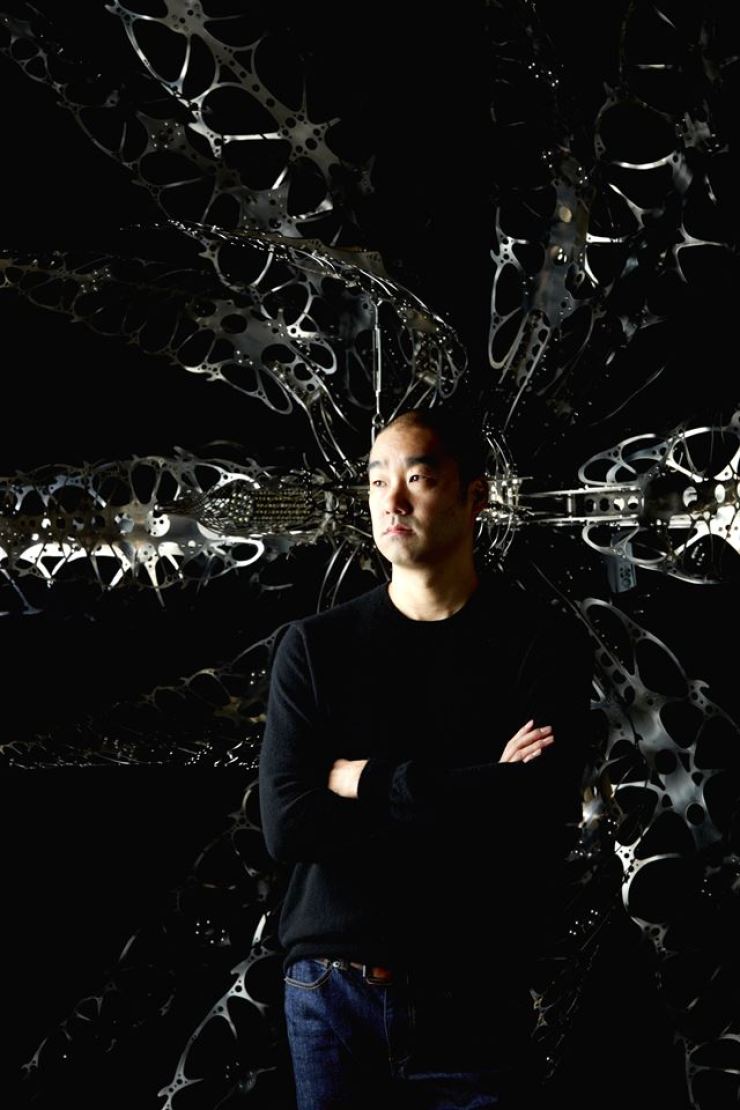

Correspondence of Mechanical Aesthetics and Natural Form

Surrounding

a central axis rotating counter-clockwise, 6 cylinders simultaneously rotate in

a clockwise direction. Each cylinder is engaged with metal plates crafted in

certain patterns, which move up and down from 90 to 120 degree angles.

There is a total of 5 layers, each with 6 decorative plates, in the shape of

wings or clouds. One metal plate on a lower layer is meshed with two

plates on an upper layer. The forms of the metal plates vary depending on the

layer, and alternate between brass and stainless steel, in terms of material.

As they move from one direction to the other, the metal leaves gather towards

the center, and then spread out, infinitely repeating the movement of opening

like a flower in full bloom and then closing, in correspondence to the title,

which means "wheel" in Sanskrit.

This

is a description of Gold Cakra Lamp (2013), which

was shown in the Lamp Shop exhibition at Gallery Hyundai.

This lengthy and detailed explanation is to demonstrate that even this work,

which is one of the simplest works made by Choe U-Ram, is invested with a

significant level of technical exquisiteness and formal beauty, both

structurally and aesthetically. It is this character,

i.e. the formative beauty of the structure and details, and the

delicate grace of movement, that differentiate Choe's moving sculptures from

other kinetic sculptures.

The

outstanding decorative beauty resembling master craftsmanship is the primary

element that captivates viewers. The movement part of Gold Insecta

Lamp (2013), also entered in the same exhibition, reminds viewers of

peacock feathers or flame-shape ornaments on a traditional gold crown, and the

gently moving shades on the Gorgonian Chandelier (2013)

are crafted in elaborate patterns resembling rocking waves or swaying seaweed.

The hand-made precision applies to all areas including selection of material,

manufacturing, engineering and production. For example, the decorative leaves

of the Gorgonian Lamp (2013) were made by etching stainless

steel plates, smoking them to kill the glaze, and sanding them to give an

antique look. The 29 pairs of wings on the Opertus Lunula Umbra

(2008), nowinstalled in the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Arts (MMCA), Seoul, were produced by making the prototypes with

ABS resin through Computer Numerical Control (CNC) processing, and attaching

wood sheets of various patterns on them, of which the best ones were cast with

silicone.

Then the final models were made with FRP plastic and colored. It is

not only the ostensible appearance of the works that requires many levels of

intervention of craftsmanship, making them worthy of the term

"labor-intensive. "Since size and shape, positions of motors and

gears differ in every work, each time a new work is planned, it must be

designed anew, down to the smallest parts, such as bolts, nuts and

bearings. Even in the case of simple works like the Cakra Lamp,

more than 150 parts in 20~30 categories are required, and in the

case of large-scale works such as the Opertus, more

than 5,000 parts belonging to some 200 categories must be newly produced.

Therefore, it is no exaggeration to say the formal level of completion Choe

achieves in his visual art is a result of the master craftsmanship in the

design and production process, and the consequent formative beauty.

Having

said this, the fact that the decorative patterns in Choe's recent works

resemble Art Nouveau is an analogy significant in many ways. The decorative

craft described earlier would be the most obvious, but a more fundamental

common point is that the origins from which the forms were drawn are similar.

Art Nouveau, famous for its vine-shaped decorations, was characterized by its

interest in organic structures inspired by natural forms, and achieved unity of

material, structure and expression through the abstraction of the slender

curves of plants by using metal, which was easy to form. The mutually

contradictory elements of the mechanical aesthetics of metal and the dynamic

nature of organisms coexist in Choe U-Ram's works as well. First of all, the

artist's pseudo life forms, known as "Anima Machines," mostly get

their motives from actual organisms in terms of form and function.

The Gorgonian

Chandelier takes after the movement of fan coral swaying in the

water, Una Lumino (2008) got its idea from the way barnacles

open, and the source of inspiration for Jet Hiatus was a

shark's teeth digging into a school of sardines. The more

decisive factor, however, is that the resemblance between the two go

beyond formal similarity, and reach structural and functional alikeness.

One of the hidden contributions of Art Nouveau, which is often mistaken as just

decorative art, is functional consistence of the form, in which the

metallic structures made for functional purposes also achieve aesthetic objectives

at the same time. E. Viollet le Duc's cast iron supports and Victor Horta's

roof trusses are not only structures, butalso decorations that bring

out the best of the sensuous curves of organisms. In Choe's works also, even

the practical parts used for movement do not lose their formative beauty.

Such

a tendency is present throughout all his work, but the early work Lumina

Virgo (2002), which is the origin of the Lamp Shop

exhibition, seems to act as a turning point in terms of unity between

decoration and function. In this small lamp, which can be turned on and off by

touching the feelers, many large and small gears are activated to open and

close the wings. These parts not only function as toothed wheels, but also form

decorations in the shape of a hand, based on Michelangelo's The

Creation. (2) Rationality, in which form and function coincide, is an

important virtue in mechanical aesthetics, and can be applied just the same in

the movement of Choe's works.

Animal Machines and Mechanical Life Forms

In

an interview, Choe U-Ram referred to his work as "a story of a machine

gaining life with the element of movement and the theme

of machine."(3) Here, the characteristic of movement is the main

aspect that makes his works different from other kinetic sculptures,which

emphasize concept or interaction with spectators. The way Choe's machines work

is inspired by the movement of living creatures. An interesting point is that

he tries to make them as natural as possible while using the

least elements. In Gold Insecta Lamp the five moving

wings are all connected to a single axis. The major axis, which is an extension

of the hind legs of the grasshopper, is controlled by a single motor,

and each wing opens and closes in sequence according to the movement of gears.

The reason the movements of the wings seem natural is because they do not open

and close at once, but move in turn, with a timelapse. When the

bottom wing is at its lowest point, the other wings are already on their way

up. The core and charm of these movements is that they are not

controlled digitally, but through an analog method based on the

simplest principles of the rotatingaxis. By using the principle that

the movement radius is larger when it is close to the rotation center, and

smaller when it is far, each wing was given a difference in the range of

motion. Such attitude of preferring simple and effective structures can be seen

throughout his working process, with no exception in the movement of birds'

wings―one of the artist's favorite motives. The two

wings of Arbor Deus Pennatus (2011) are also controlled by a

single motor. The gears connected to the motor rotate along with other engaged

gears, and the two axes connected to these gears move in different rhythms,

thereby creating a natural and elegant movement.

The functionalist aesthetics,

combining beauty and efficiency, is identical to the physiological principles

that constitute the bodies of animals. Construction to achieve the most

efficient function results in beauty. The analogy of machines and animals is a

fundamental aspect penetrating all of Choe's works. His motivation for

obtaining subject matter is animals or plants, and he designs his detailed

structures and movements from the skeletons or movements of actual life forms.

Furthermore, his principle of motion that pursues economic efficiency, and his

final goal of creating "life as it could be"(4) are all based on the

combination of machine and living thing. The comparison between animals and

machines has a long history, tracing back to the age of enlightenment.

Descartes claimed that animals were machines made only with matter, and saw

humans also as mechanisms that moved according to mechanical arrangement, just

as clocks or automated dolls move according to the placement of counterweights

or gears, besides having souls.(5) Such a doctrine of the human machine was

compiled by La Mettrie, who defined the human body as "a machine which

winds its own springs," and "the living image of perpetual

movement."(6)To the materialist La Mettrie, who thought the soul was also

a function of the brain, a thinking muscle, movement of the human was merely

mechanical, and something maintained through the energy transported by blood,

circulated by the heart―a certain

hydraulic device.(7) Theperception of "an automated machine with its own

principle of movement" sees humans as a kind of automatic dolls. Such

discussions were later demonstrated in reality with the support of precision

mechanical engineering and the growing interest in anatomy. Examples include

Jacques de Vaucanson's mechanical duck, which was famous for eating and

excreting, and Jaquet-Droz's writing automaton, which is still functional.

These examples belong to the genealogical roots of Choe U-Ram's automata in

terms of both philosophy and engineering.

Between Automatic Doll and Artificial Life

There

are complex reasons for considering Choe's mechanical life forms as reversions

of the 18th century automata. First, theyare both elaborate

mechanical devices with carefully designed internal structures, and are similar

in the way they link anatomical structure and function with the machine.

While de Vaucanson imitated humans' breathing organs when

he made the Flute Player,giving it levers and valves to move its lungs, airway,

lips and tongue, Choe U-Ram mechanically embodied a bird's flapping wings, based

on the dual structure of an actual bird skeleton, consisting of the radius and

ulna, in Arbor Deus Pennatus. The more fundamental

similarity, however, lies in the motive or desire to make the mechanical

device.

Choe's works are often discussed in association with the

fusion of art and science, artificial life, robotics or cyber art, but in fact

his works are in principle true to the basics of mechanical dynamics, which

consist of motors, gears, and dynamic components, and are only assisted by a CPU

board to control the pattern and time of the movement. His fascination with

machines is something Choe has confessed in many interviews.

The automative dolls of the 18th century also began from the dreams

of inventors, who wanted to make a machine that was more than a machine, by

applying the highest level of precision and technology. (It is no coincidence

that many works by Choe U-Ram remind us of elaborate clockwork.) Moreover, the

"moving" automata share the characteristic of ultimately trying to

imitate or create life. This is because movement is the inborn nature of life,

and whether something can move on its own or not becomes a standard of

determining life. The reason Choe's clearly lifeless machines with metallic

bodies feel like they are in fact alive is due to lightand natural

movement, which are the symbols of life.

From

the perspective of life, it is quite suggestive that there are many

"breathing machines" among Choe U-Ram's mechanical life forms. The

thrilling dance of the Opertus Lunala Umbra, which is the

largest and the most visually overwhelming among his works, begins with the

ribs or shells of a crustacean moving up and down in gigantic breaths. The

secret of the popularity of Custos Cavum (2011), which was

the greatest hit in Choe's 2012 solo show at Gallery Hyundai, was

that it resembled a sea lion breathing in a realistic fashion. The core

mechanism that makespeople believe the machine is alive, is the

difference between the rapid inhaling and slow exhaling motions. A lifeless

being breathing is a sign that it has become a living thing, and it is an act

of bestowing the status of god to the maker. This is because the ontological

ambition indwelling in all automated dolls is in fact a Promethean rebellion,

an overtaking of the privilege of creating life. In that sense, the artist's strategy

is to give a more solid status to his "life as it could be," by using

the authority of science in his pseudo-scientific Latin

names andecological reports(imaginary birth legends), which often

accompany his sculptures.

Ultimately,

Choe U-Ram's mechanical life forms transcend the dream of the automated doll,

which attempts to imitate nature. His "experiment to study the relation

between a newly born species (machine) and human society through the way

humans' creations group and multiply on their own" (quote by artist)

transcends "life as we know it" and extends to another artificial

life that moves according to its own logic and free will. They not only imitate

existing organisms, but mix up the borders of categories by mutually combining

heterogeneous elements. The movement of a jet engine and a shark's teeth are

fused to breed a machine with an animal (Jet Hiatus), and an

animal-plant hybrid is made by crossing a barnacle and a flower (Una

Lumino).

Furthermore, these quasi life forms make up an ecosystem

where adult and larva, or male and female coexist (Urbanus

series (2006)),represent interacting imaginary mechanical life forms in a

community (Una Lumino), and advance from individual beings towards forming a

part of nature or the universe. (Kalpa (2010), a cosmos

series that retraces the origin of life, is at the end of that path.) What is

important here is not how much these virtual life forms satisfy the scientific

definition of artificial life, but how much they contribute to reconsidering

and extending the concept of life on the horizon of imagination. This is the

point at which Choe U-Ram's work functions as visual art, and the reason why

his mechanical life forms serve as a contact point for remediation(8) with the

18th century's dream of the human automata, and the 21st century's pursuit of

artificial life.

(1)

Gaby Wood, Edison's Eve: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life

(New York: Anchor Books, 2003), p. 14.

(2)

Though with a different emphasis, in the introduction to the 2006 exhibition at

Mori Museum of Art, Kim Sunhee also noted Lumina Virgoas a work

representing Choe U-Ram's entire body of work. Kim Sunhee, "Alien Life

Forms: The Art of Choe U-Ram," City Energy-MAM PROJECT 004, Mori Museum of

Art, 2006, p. 31.

(3)

Interview with Aliceon on January 18, 2009.

(4)

The term of Christopher Langton, who established the concept of artificial

life. Langton expanded the concept of life from "life as we know it"

to "life as it could be." Christopher Langton, "Artificial

Life," Artificial life: the proceedings of an interdisciplinary workshop

on the synthesis and simulation of living systems held September, 1987 in Los

Alamos, New Mexico, Volume 6, Santa Fe Institute studies in the sciences of

complexity (Addison-Wesley, 1989).

(5)

Gaby Wood, Edison's Eve: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life

(New York: Anchor Books, 2003), p. 10.

(6)

Julian Offroy de La Mattrie, Man a machine, tr. Gertrude Carman Bussey

(The Open Court Publishing Co., 1912), p. 93.

(7)

Young Ran Jo, "La Mettrie's Mind-Body Theory in L'Homme Machine and Life

Sciences in the Eighteenth Century," Korean Journal of the History of

Science, Vol. 13, no. 2, 1991, p. 148.

(8)

Used by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, the term refers to how new

media uses existing media or other contemporary media for

reorganization. Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding

New Media, MIT Press, 2000, pp. 3-15.