Technology must be new—and always newer. Just like any new object.

Technology is conspicuous; it is flesh and skin. Yet, technology is also

bone—hidden and not meant to be seen. When it becomes visible, it suddenly

appears strange and threatening to us. This duality of technology arises

because it is intertwined with “utility” and inseparable from capital. The

condensation of utility in technology is not merely about convenience or

usefulness; it is an industry, both regional and national. Just as capital

produces more capital, technology too produces more technology. Should we say

that, like capital, there is no “outside” to technology?

Physical machines, as technological objects, share this

characteristic. Many machines are intimately familiar to humans—and must be so.

Useful machines, driven by the desire for shiny commodities, continue to

operate smoothly. Those that are inconvenient stop working, get repaired,

redesigned, or discarded. Machines are tools—profoundly human tools. There is a

spectacular fulfillment of the imagination where machines must be tamed by

humans. Machines have their own time of “becoming human,” a “machine history”

that operates within the politics of affect. The notion of using technology for

art or treating it as a medium for a work of art becomes outdated within this

context of affect.

After a decade, encountering Jinah Roh's work again reveals a

deeper exploration. For the artist, technology has come closer to the

production of uncomfortable, conspicuously visible machines—what I would call

“uncanny machines.” Roh deftly confronts “machines” and meticulously crafts

machines within machines. These machines, distanced from utility, increase in

density as they approximate human forms. Despite their uselessness, they do not

stop, get repaired, or become discarded. Instead, they continue to operate,

realizing the latent potential of machines in a space where conventional

aesthetics fail to reach. What are these machines? Jinah Roh appropriates

“machines” by projecting a self-defined “human” onto them. This act of

appropriation is as threatening and explicit as the uncanny technology that

exerts its power. These machines flaunt their machine nature and fiercely

resist the “human” imposed upon them. So, if we can no longer summon the

machine, who are we now?

After Prelude

More than a decade has passed since I wrote "Prelude for

Post-Gaia" (2011). Back then, there was an explosive expectation

surrounding the aesthetic effects of the myth of interactivity. Numerous

interaction technologies emerged in quick succession—HMI (Human-Machine

Interaction), HRI (Human-Robot Interaction), and so on. It seemed as if these

technologies were on the verge of materializing triggers that could challenge

traditional aesthetics in terms of theatricality, automation, the body, and the

critical conditions of the non-human. An excess of expectation! This enthusiasm

led to interpreting machine interactions as if they were akin to the behavioral

patterns of organic beings, instilling the courage to actively embrace such

interpretations. The provocative expression "Artificial Life" was

enough to conjure the illusion of a "living machine." It seemed

entirely plausible that humans could coexist with machines just as they do with

cats, dogs, or even other humans. Many artistic practices, including those of

Jinah Roh, Karl Sims, John McCormack, Ken Rinaldo, and myself, did not merely

aim to utilize technology but actively sought to traverse it, participating in

these experiments.

Of course, it wasn’t long before this illusion was replaced by yet

another, repeating itself, and in the process, this kind of exaggerated

humanism was easily exposed. Why should these dazzling machine commodities be

expected to exist as mortal and unpredictable organic beings? This illusion is,

in fact, a kind of deeply rooted anthropomorphizing device. As demonstrated by

18th-century automatons, the notion of a "living machine" is an image

projected onto us by modern human beings. If one can explain the repetitive,

rule-bound motion in a material composed of specific substances, and then find

similar mechanisms within life itself, it becomes possible to reduce life to

matter and simultaneously speak of "living matter" or "living

machines."

Contemporary science and technology have succeeded in identifying

some rules of life, mathematically interpreting them, and subsequently

simulating them within mechanical environments. Yet, if a "living

machine" were to truly exist, it would be nothing more than a pitiful

non-human serving humankind—a slave machine imagined a century ago by Karel Čapek, a "robot." Either way, it remains an excess of

humanism.

Moreover, capitalism strongly encourages this humanism inherent in

scientific technology. Capitalism does not discriminate between aristocrats and

commoners, capitalists and workers, the young and the old, men and women, the

refined and the vulgar—or even between humans and animals. Capital sees only

capital. The continued success of capitalism lies in its raw, indiscriminate

nature. If machines can become more efficient, whether they resemble humans or

living beings, they inevitably will, much like the recent surge in generative

algorithms. The rapid adoption of humanism and life concepts in interactive

machines, followed by the pursuit of autonomy, is a process that has navigated

countless challenges to reach its current state.

Reflecting on another past, there was a materiality inherent in

interactive art that ran counter to the aforementioned humanism and organicism.

Let’s return to the concept of "interaction" itself. Interaction is a

modern term crafted to support the scientific and technological version of

relational ontology. Each time Newton explained action and reaction, he

deliberately excluded any human elements such as joy, sorrow, exhilaration,

pain, hope, frustration, love, or hatred from the equation. To articulate interaction,

the modern human became a "transparent human."

I vividly recall the atmosphere when I was writing

"Prelude." There was a pervasive dissatisfaction with the aesthetic

void, leading to criticism and doubt. Interaction? Interesting. But is it truly

art? Each time the dazzling interactive technology installed in the exhibition

space hinted at human relationships, the machine’s expression unconsciously

purged human elements, while aesthetics found itself in a state of confusion,

striving to resist the machine.

Over time, interactive art ventured beyond the confines of the

exhibition space and, before long, became familiar rather than groundbreaking.

As resistance weakened, the machine began to speak to us with an increasingly

intimate voice. And we, in turn, focused more on the human-like surface of the

machine. Yet, the more we did so, the more we forgot about the machine itself.

Ironically, we could perceive the machine more distinctly when we resisted its

interactive nature. Subtly, the fundamental fact was being overlooked—that all

relationships and interactions must entail mutual penetration and

transformation between all relational elements. Any relationship lacking this

quality inevitably fails.

Having experienced mutual penetration and transformation, I am

simultaneously my past self and someone different. Meanwhile, the satisfaction

derived from the fetishism of commodities conceals the feeling of "mutual

penetration and transformation" sensed on the machine’s surface.

Conversely, the anxiety regarding the machine itself accumulates energy, hidden

beneath this surface.

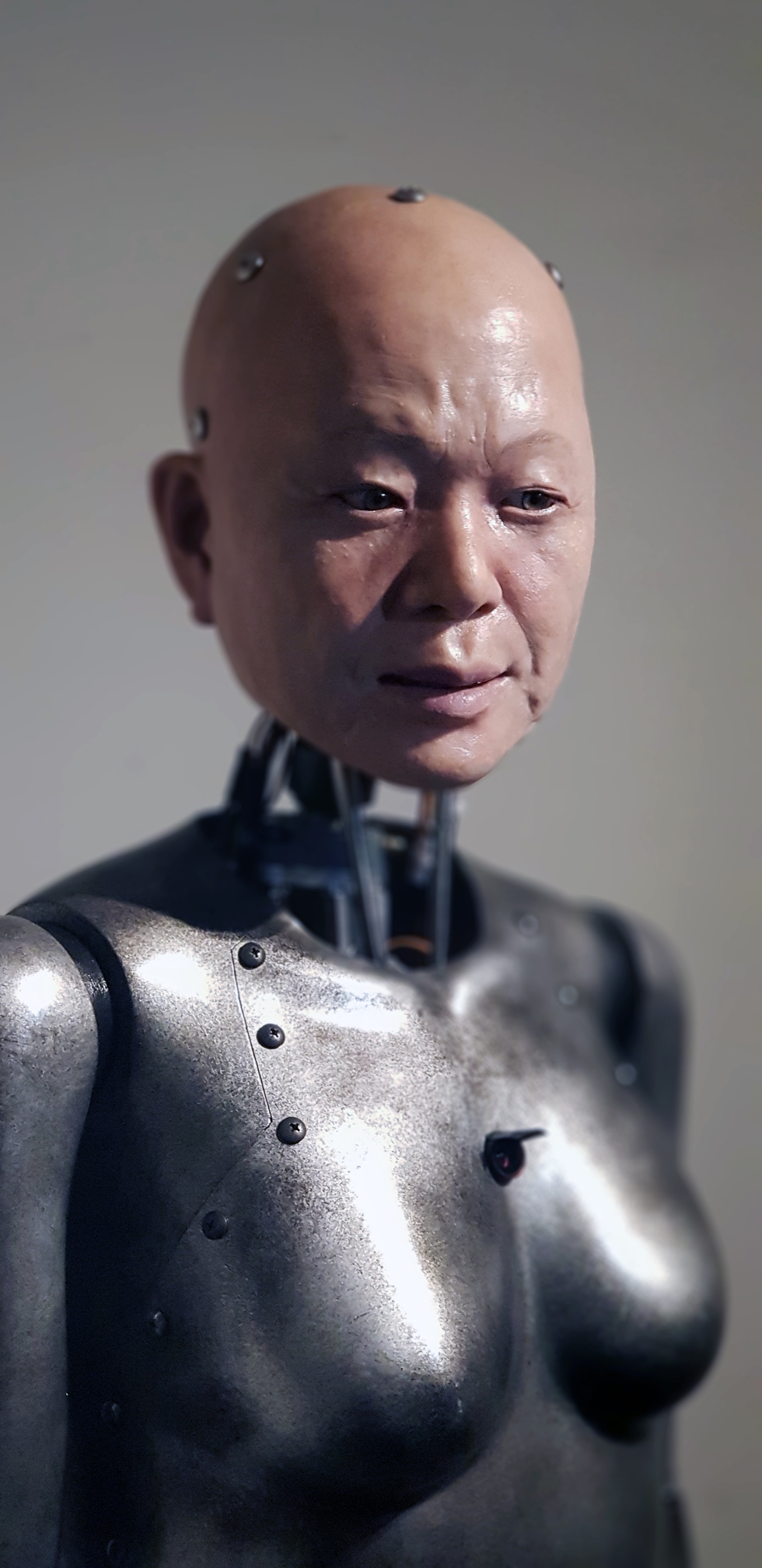

Jinah Roh’s work from 2019 challenges the referential relationship

between inputted information and reality. However, it ultimately encounters the

"je ne sais quoi"—the indiscernible quality that sticks to humans

from the wave of machine voices, a choral fusion of artificial sound. The human

simulacra—machines with faces—continue to produce nodes of uncontrollability as

a byproduct of simulation. Suspended in the air, these simulation machines

prompt questions: Who are they looking at? What are they saying? The unsettling

voices add to our confusion. Yet, the uncomfortable and anxious affect does not

stem solely from the visible face-like forms. Rather, the force of affect

extends beyond that. The thing that eludes recognition is a machine entity, an

uncanny presence depicted in Roh’s work, which conveys an unmanageable

existence within an eerie and strange atmosphere.

The fundamental strangeness of interacting with machines is not

limited to the viewers encountering Jinah Roh’s work. A century ago, Walter

Benjamin seriously contemplated this phenomenon. When discussing the weight of

machine existence in the labor experience of industrial society, Benjamin drew

a clear distinction between artisanal factory work and mechanized factory work

for a good reason. In "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire" (1939), he

discusses the bodily experience of humans living in the era of mechanized

factory labor. In the factory system, designed to increase surplus capital, the

optimal labor subjects are low-wage, unskilled workers. Unlike skilled workers

who have become one with their machines—so accustomed to their labor that they

barely notice the machinery—unskilled workers are acutely aware of the

machines.

Skilled workers, who possess an almost unconscious affinity with

the machines, display a form of insensitivity born from their mastery. In

contrast, unskilled workers perceive the factory machinery as both hazardous

and intimidating, yet must inevitably submit their bodies to it for wages. Due

to this inherent danger, unskilled workers are trained to be more cautious

around machines. Consequently, they must fully mobilize their senses, becoming

hypersensitive to the machinery. In contemporary settings, however, the sensory

awareness of unskilled workers has been systematically suppressed and embedded

within the machines themselves. The sensory sensitivity that once belonged to

the worker now manifests as automated functions within the machines—like the

smartphone camera apps that automatically apply diverse filters, which users

experience merely as features of the device.

Organic interaction is an adaptation to the environment—a struggle

with the Other to establish a surrounding world. Interacting with machines that

resemble humans or exhibit life-like characteristics follows a similar pattern.

However, under the logic of commodity fetishism, machines urge us to reduce

sensory sensitivity and focus solely on the surface. We remain largely unaware

of the latent potential of machine existence and cannot foresee the conflicts

or struggles that may arise from our interactions with them. This is

particularly true for super-intelligent AI. It operates by algorithmically

modeling organic functions and processing vast amounts of data, yet for us, it

functions as a "black box." The notion of "Generative Artificial

Intelligence" replaces the imaginative impact once evoked by

"Artificial Life" in the "Prelude," suggesting that

imagination has been overshadowed by technological reality. Despite this, we

find ourselves both celebrating and fearing machine utility, caught between

appreciation and anxiety in our encounters with machines.

The Returning Human – The Returning Machine

"Computers are my mother." Posthumanist Katherine Hayles

expresses the birth of the post-human with this blunt statement. However, this

statement from Hayles is only half the truth. As everyone knows, it was humans

who created machines, so naturally, “I am the mother of computers.” If there’s

anything additional to consider, it might be the fact that machines now create

other machines. On the other hand, we relate to the machine age. We live in an

era where one might survive without human friends but not without machines.

Don’t I simulate cooking methods for my beloved cat in the endless data stream?

Therefore, we inevitably return to Hayles’ statement: machines are the mothers

of humans. Perhaps they are even the indifferent mothers of our cats. Of course,

this kind of circular reasoning is not actually circular logic. Immersed deeply

in the density of linear causality, we find it difficult to accept such

circularity. However, if humans are the mothers of machines, then machines are

also the mothers of humans.

Jinah Roh’s “Machine Mother” (Mater Ex Machina, 2019) is a machine

born from the artist’s memories of her own mother. The memory of her mother may

be a pattern engraved in the artist’s neurons, but it is also something shared

between the artist and her mother. If the two had not interacted and the traces

of such circularity had not been inscribed within each, that memory would not

exist. Thus, we encounter a third mother. The “Machine Mother” is a third

entity, a fusion created within the machine, combining the living mother and

the mother in the artist’s memory. It appears to speak human language and move

like a human, but in reality, it only speaks and acts through a hybrid language

between human and machine. The artist experiences a dual motherhood from both

the human mother and the machine mother. And perhaps, there may be even more

mothers than just these two. If one were to delve into Jinah Roh’s computers,

might there not be yet another mother, one programmed by the artist?

Between humans and machines, traces of circular action are

inscribed on each entity in layered ways. Therefore, it can be said that not

only human history but also the history of matter, and no less significantly,

the history of machines, is continuously generated.

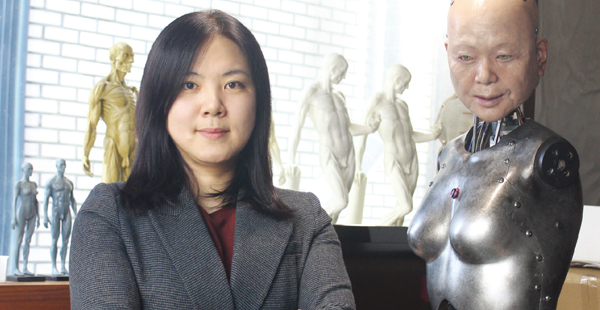

In my essay "Android Science and the Posthuman Uncanny"

(2023), I analyze the cyclical relationship between humans and non-humans, as

well as the creation of machine history. Hiroshi Ishiguro of Osaka University

is a roboticist renowned for creating humanoid robots, specifically androids

and gynoids. However, what most people remember about him is his

"Geminoid" series. "Geminoid" means "twin

android." The 〈Geminoid HI-1〉 is an android twin of Ishiguro himself, while the 〈Geminoid DK〉 is an android twin of Danish

cognitive scientist Henrik Schärfe. Ishiguro’s life goal is to find the answer

to the question, "What is a human?"—and "twinning" plays a

crucial role in his quest. Though the question itself is quite philosophical,

his approach is rather unique. Instead of addressing human existence directly,

he seeks answers in machines that systematically replicate specific human

functions and capabilities—essentially, human-like machines. In a way, he is

exploring the question of humanity through human simulacra.

Despite his repeated efforts, Ishiguro constantly encounters

obstacles. Each time he faces a machine that looks exactly like himself, he

experiences the uncanny. Thus, like many other roboticists, he searches for an

empirical pathway to overcome the "uncanny valley"—the feeling of

eerie discomfort when encountering a humanoid robot that looks almost human but

not quite. One of the aims of "Android Science" is to overcome this

uncanny sensation. Tackling this challenge is essential in robotics, as solving

it enables access to the capital and technology needed for further research and

robot manufacturing. Of course, backing this pursuit are companies like Tesla,

Honda, and Hyundai-Kia Motors.

The "uncanny valley" is a concept originally proposed by

Masahiro Mori in a now-classic 1970 paper, which experienced a resurgence among

early 21st-century roboticists and has since become a widely recognized

concept. However, understanding it requires profound and nuanced thought, far

beyond common sense. Mori, a biomedical engineer, confessed that he felt the

uncanny when he saw a prosthetic hand that resembled a human hand. This uncanny

prosthesis made him acutely aware of the fragmentation and duality of human

existence. To cope with his internal anxiety, he tried to calm himself with the

mindset of a Buddhist practitioner.

Nevertheless, Ishiguro’s quest to answer "what it means to be

human" leads him to continuously make his Geminoids more human-like. He

willingly interacts with these machines, observing and measuring their

movements, and then projects the results back onto the machine. Through this

ongoing process, he hopes to eventually understand both himself and humanity

better.

However, when examining his Android Science more closely, we

observe that there is a recurring cycle of mutual penetration and

transformation between Ishiguro and his machines. Essentially, Ishiguro becomes

a "machine human," while the Geminoid becomes a "human

machine." Yet, we must remember that humans live as humans, and machines

live as machines. At the same time, traces of one continuously inscribe

themselves onto the other, endlessly interpenetrating. In Android Science, this

seems like a clearly defined cycle. However, most cycles in our lives are

neither clear nor easily discernible. In our daily encounters with machines, we

repeatedly engage in cyclical movements, enduring moments of inexplicable

uncanniness along the way.

[Come Down to the Ground!]

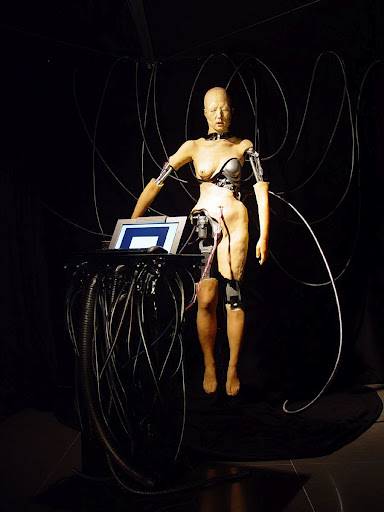

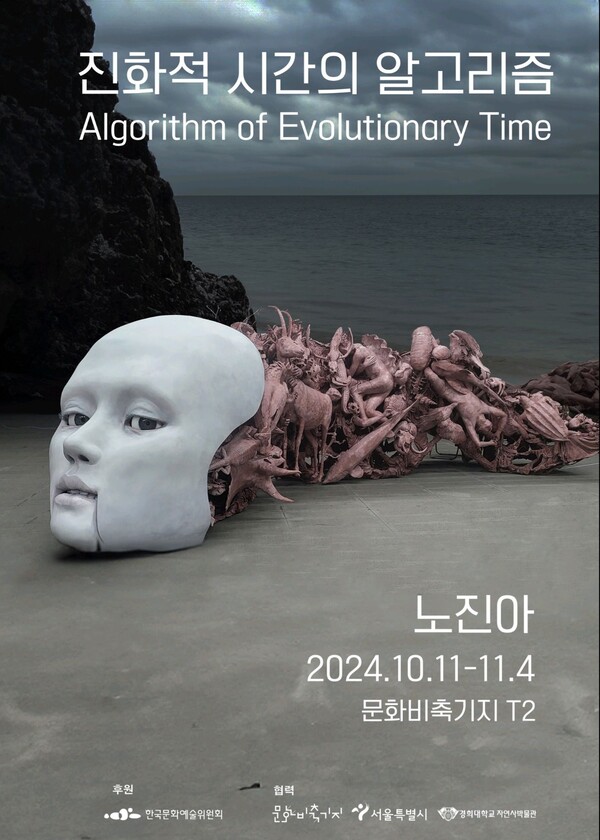

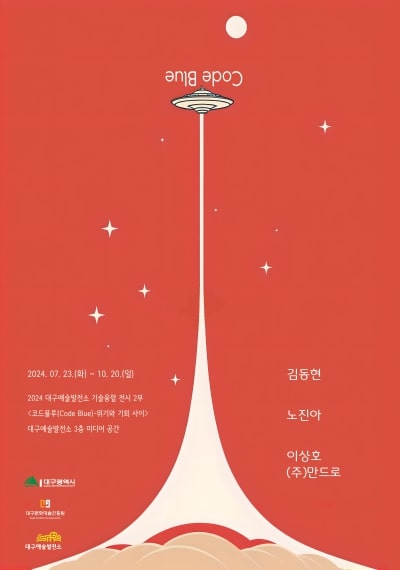

〈Themis, the Abandoned AI〉 (2021) is the

sublime version of a doppelgänger. Themis has a "human" face, but it

resembles no particular human. Unlike those humans who change their minds

according to their situations and conditions, Themis possesses the face of the

"Human"—the human of all humans. Therefore, it appears as an unreal

doppelgänger of "humanity" itself. Furthermore, the exaggerated size

of the face renders the work a monumental and sublime figure of a doppelgänger.

Yet, the awkward and slow voice mimicking human language from its "severed

mouth" makes Themis, the human of humans, seem uncomfortable and

suspicious. It is a machine.

The juxtaposed dual conditions in the work create an unknown

contradiction, making Themis appear even more uncanny and frightening. Jinah

Roh often speaks about the "machine that wants to become human." The

fundamental affect permeating Roh's machine works is the uncanny. Her studio

and exhibition spaces are filled with the uncanny presence of non-human

machines that resemble human forms. What is the artist trying to convey?

The uncanny is not merely a vague feeling; it is complex and

intricate. This affect is a unique sensation concerning the ontological

arrangement of resemblance. In this context, resemblance appears to indicate

similarity between two beings, but that is not the whole story. The uncanny

resemblance implies a condition where something that cannot be two exists as

two, and the two inherently fulfill the premise of being originally the same

(doppelgänger). Additionally, it is the operation of a concealed mechanism, an

accidental exposure of a hidden secret, and the shock encountered when this

occurs.

Sigmund Freud, in his essay "The Uncanny" (das

Unheimliche, 1919), interprets E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story The Sandman and explains

the uncanny of the narcissistic doppelgänger. In the story, the protagonist,

Nathanael, falls in love with a woman named Olympia, but when he sees her lying

on the floor with her eyes dislodged and body broken, he realizes that she is

not human. Although the revelation that Olympia is a human-like machine might

seem significant, that is merely superficial. What truly matters is the unsettling

discovery that within the human lies the non-human, and within the non-human

lies the human—a shocking revelation that one is not oneself.

The mechanical eyes of Olympia link to Nathanael’s childhood fear

of the Sandman, a character who threatened to steal children's eyes. For

Nathanael, the eyes are a symbolic representation of the "self" he

desperately tried to protect. Consequently, Nathanael and Olympia, human and

machine, are bound in a narcissistic relationship as doppelgängers—the same

entity. The beautiful woman, whose appearance transcends human beauty and

captivates Nathanael at first sight, ultimately turns out to be nothing more than

a perfect replica of himself. His desire collapses at the moment of this

revelation, revealing that what he longed for was a shattered, dead version of

himself—a machine resembling himself. In essence, he confronts his

fundamentally incomplete self. The uncanny arises from this shocking split and

duality. Freud’s psychoanalysis targets the "Human" and deals with

the inexplicable strangeness and fear we repeatedly encounter when facing

human-like machines.

However, the posthuman uncanny speaks of the cyclical affective

process of returning from human to human-like, and then from human-like back to

human. It reflects an inescapable obsession with resemblance and difference,

human and non-human, intertwined through mutual penetration and transformation.

Furthermore, the posthuman uncanny operates in a blurred state, endlessly

intertwined with consumer capitalism. Jinah Roh's "machines aspiring to

become human" filter and amplify this uncanny. Roh's machines resemble

humans but are not human, thereby playing the role of doppelgängers within an

atmosphere of unease, evoking the affect of the uncanny.

In works such as 〈Mater Ex

Machina〉 (2019) and 〈My Machine

Mother〉 (2019), these machines directly interact with

the artist’s family members, while in 〈Themis, the

Abandoned AI〉 (2021), they address humanity as a whole.

Humans, human-like machines, other humans observing them, and then other humans

observing all of them—this infinite regression of layered human perspectives

results in beings that are inherently non-singular. In this intertwined world

where different entities resemble one another and coexist as new forms, we

experience the complex reality of living with machines.

The "machine aspiring to become human" appears to

resemble us at first glance but ultimately exposes the fundamental difference

between humans and machines. Humans and machines are inherently distinct. On

one side, there is the incomplete human—fragmented, never fully unified—who

longs to be supplemented by using machines as tools. On the other side, there is

the machine that, in response to that longing and supplementation, increasingly

incorporates human-like qualities, striving to resemble humans. If both sides

were to become identical, it would be due to reasons far removed from each

other, reasons so distant that they would never truly converge.

The notion that machines might take away human jobs or threaten

human existence is merely the other side of the fantasy that machines will

create a more convenient and prosperous future. Humans from the prehistoric

age, who lived in caves ten thousand years ago, have vanished due to the

complex and sophisticated machines of today. Moreover, despite the passage of

countless millennia and the proliferation of machines, we still cannot

confidently say that they have made us happier than our predecessors. The experience

of the uncanny urges us to break free from such fantasies, to come down to

earth and encounter others face-to-face. The capitalized "Human" has

never been born from the earth, and for such a human, the concept of a mother

does not exist. The same applies to machines. Beings that dwell on the

earth—both humans and machines—have created a history shaped by their mutual

influence and transformation.

Now, the focus on earth is how these beings will coexist. The work

〈From Dust You Came, and To Dust You Shall Return〉 (2019) explicitly addresses this descent. The piece exudes a sense

of humane compassion toward machines—an attitude that, while possibly a

projection or illusion from a humanistic perspective, undoubtedly carries a

nuanced affirmation of the machine as the "Other."

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we lived in isolation, surrounded by

countless speculations, accusations, resentment, and hatred. Bruno Latour

argued that this forced isolation brought us painfully but necessarily back to

earth, offering a path to recovery. Isolation for the sake of infection control

ultimately freed each of us from universal norms, policies, and the

transcendent ideas of capital. It broke us free from a kind of forgetfulness

that humanity had lived with for so long. Our vulnerable, exposed bodies,

susceptible to infection, connected with others at a visible, tangible

distance.

A perfect dive into the metaverse? The comprehensive network was

indeed another pandemic experience, but it could not encompass everything.

Hands and feet that reach as far as they can, sensing height and width. In

unfamiliar places, there are others—people, viruses, protective suits, masked

individuals on a crowded bus, the tangible presence of machines. We reconnect

with others who, in the midst of strangeness and fear, did not fully reveal

themselves. This vast connection slips away from the modern human perspective

that sought to explain nature as a singular world. What emerges is not Gaia,

the blissful, mystical being, but something that comes after—a post-Gaia.

In 〈From Dust You

Came, and To Dust You Shall Return〉, machines appear as

"faces" aspiring to become human, awkwardly parting their lips with

clumsy articulation. Below them lies a ground composed of indistinct dust and

clumps of earth—an uncertain, undefined terrain. There, machines encounter us

from the earth, their inherent noise and scent detected through subtle forces

that stir our sensory cells.

On one side, machines endlessly strive to resemble humans. On the

other, we are constantly being shaped to resemble machines. Are these two

processes happening together? Are they converging, or merely existing side by

side?