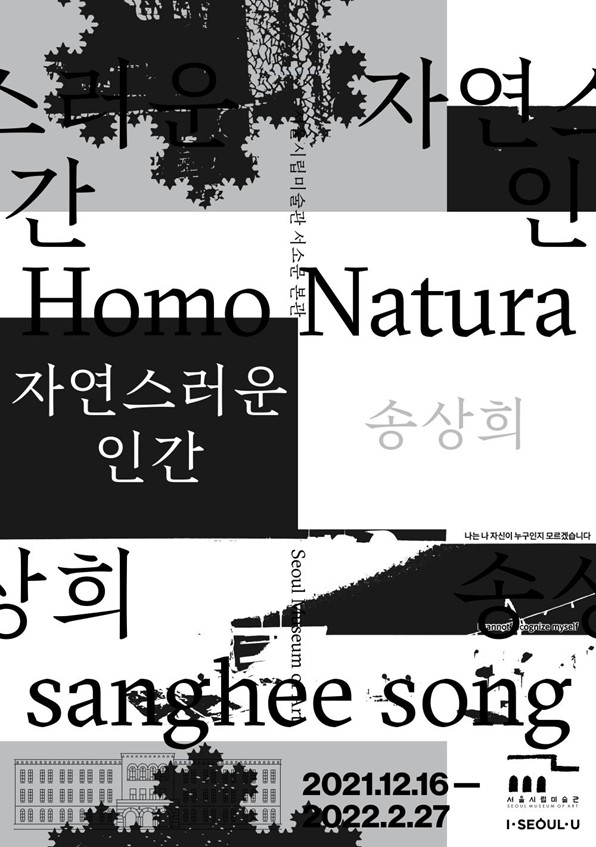

Song

Sanghee is an artist who exemplifies the growth and development of Korean art

venues since the 2000s. Around the turn of the millennium, Song took part in

various activities at alternative art spaces, which were then beginning to

flourish, helping to reinterpret the legacy of Minjung art (or “People’s art”)

and feminist art. She soon began gaining renown for her agile experimentations

with important topics and practices that reflected the development of Korean

art, such as the emergence of public art, works based on archive analysis and

research, and projects that combined performance and media. By the 2000s, many

artists who had studied abroad were returning to Korea, and they helped to

transform the infrastructure of Korean art by emphasizing artistic expertise

and asserting the need for a public system supporting such expertise. Through

the course of this development, Song Sanghee has been one of the few Korean

artists with no international education who has been invited to join publicly

funded exhibitions and residence programs, both at home and in other countries.

As such, she has traveled through Korea and other countries, participating in

residency programs and creating diverse works.

Most

of her early works were very dense compositions examining the relationship

between the body (flesh or corporeal entity) and history, society, memory, and

emotion. But since establishing herself in Amsterdam in 2006 (after being

invited to a residency program of the Rijksakademie), she has greatly expanded

her topics and the overall scope of her artwork. Unfortunately, however, some

projects that she spent considerable time planning and researching have fallen

through due to a lack of financing or support. With 2016 marking the tenth

anniversary of Song Sanghee’s relocation to Amsterdam, the time seems right to

revisit some of these projects. With the public support of the Korean art

world, Song can finally bring these projects to fruition so that her exceptional

artistry can be seen from a new perspective.

Both Korean and international critics have interviewed Song and written

in-depth about her various works. However, one important early work that has

not been adequately covered is Cleaning (2002),

which may be seen as a seed that contains her fundamental artistic attitude and

interest. Cleaning is a performance work, wherein

Song wore an outfit of black leotards covered with adhesive tape, and then used

the sticky surface of the tape to collect dust that had settled in the corners

of Korean middle-class homes. With this performance, she caricaturized her

(political) identity, but also made it into a fable, while highlighting her own

self-sacrifice and degradation. As viewers quietly observe the honesty and

earnestness of her postures and movements, they are forced to rethink emotions

such as shame, anxiety, and discomfort, resulting in a type of psycho-therapy.

The ultimate effect is an increasing will to face the truth. This effect is elicited

even more dramatically in other works, when Song performs as the protagonists

of myths, heroes of the people, or victims of historical events.

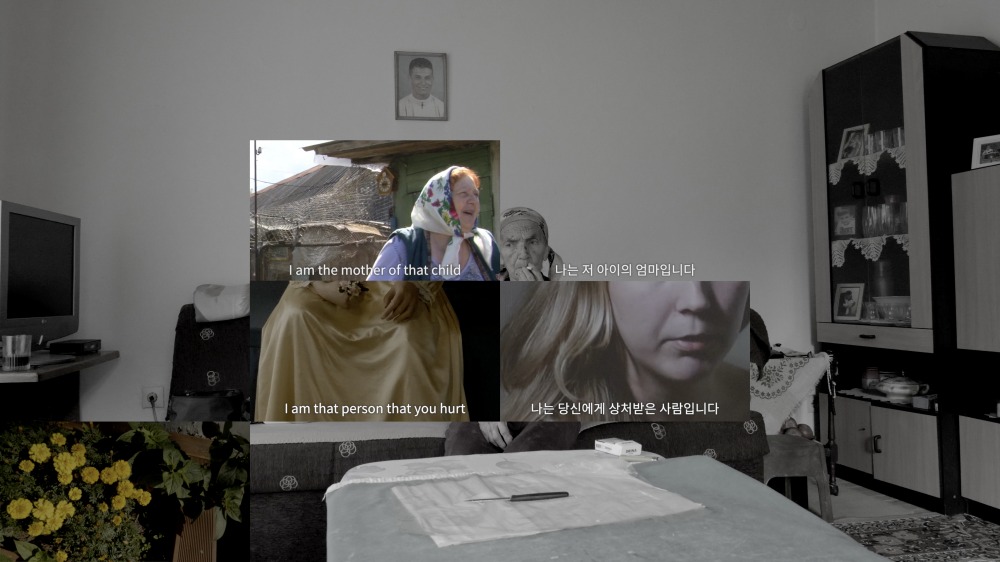

Although

they often address monumental events and people, Song’s works are never

saturated with the conventional meaning inherent to monumentality. Instead,

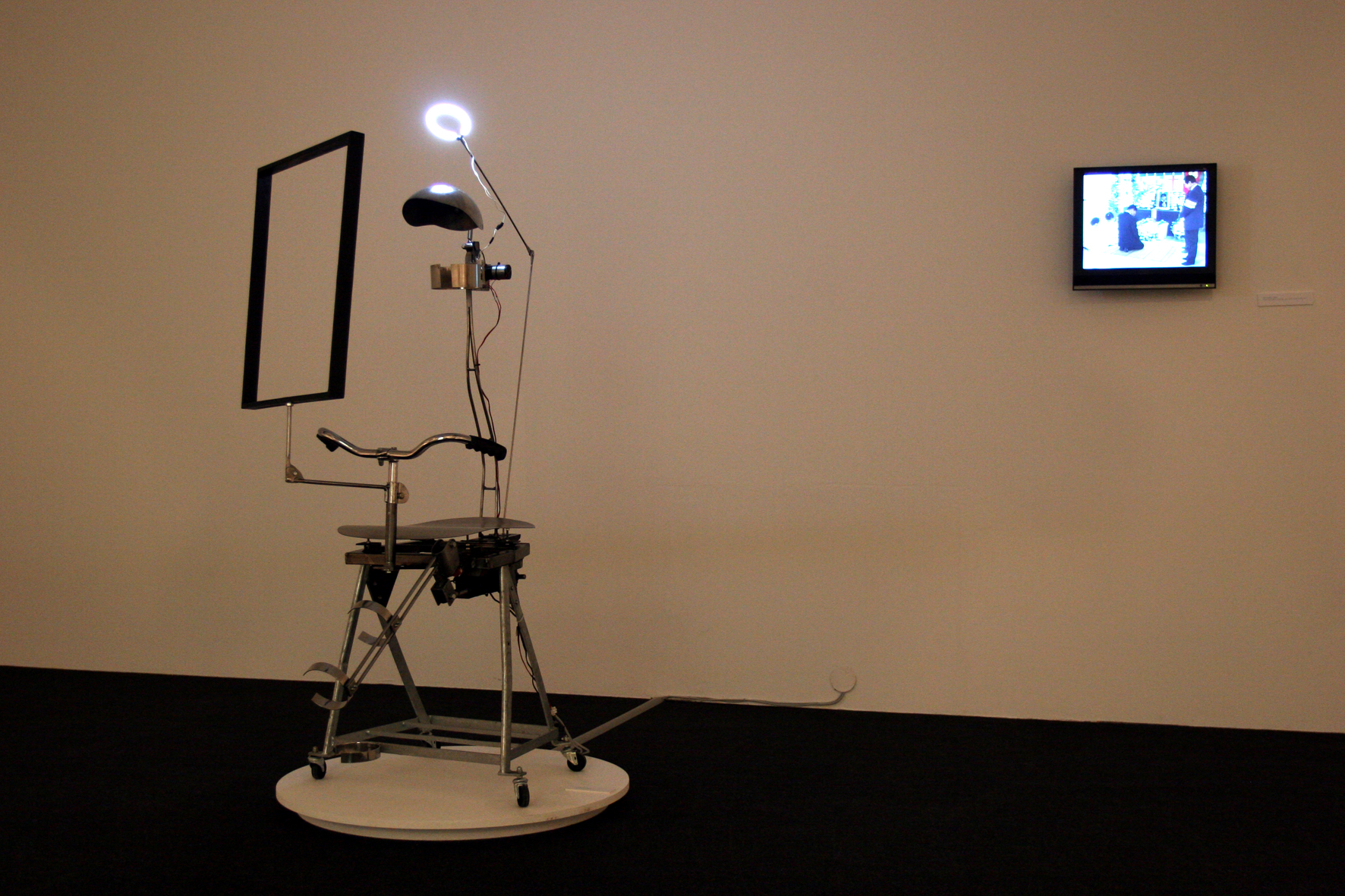

they generate heterogeneous textures. Since 2010, as she has infiltrated the

history and culture of Europe, Africa, and East Asia, her narratives have

become more complicated and her apparatus for developing them has become more

elaborate. To create multi-layered performance works that tell various stories,

she has increased the depth and duration of her preliminary research,

conducting interviews and reviewing literature. Accordingly, her media has been

diversified and mobilized, even allowing for custom- or self-made media. She is

particularly fascinated with storytelling techniques borrowed from popular

culture, such as heroic stories, legends, espionage, and science fiction.

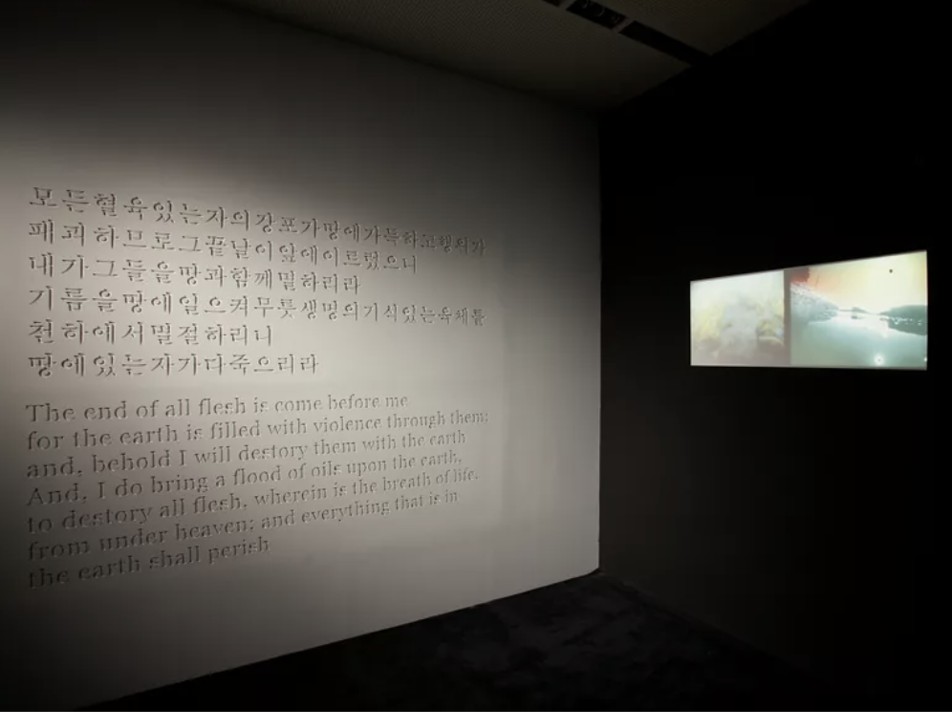

In

some cases, these techniques are concealed within the internal structure of her

works, while in other cases, they are intentionally exaggerated. On the

surface, they are loosely connected through the fragmentary characteristics of

montage, but they also show an emotional consistency that emerges from the

powerful tones of music and color. Having recognized the complexity of her

topics of choice, she pursues them through labyrinths where suppressed states

of awareness returned. In the end, the largest monument that she has

constructed is a memorial to death. Whether it commemorates the death of an

individual, a group, or the earth, she has built this memorial through her

sensitive empathy, strong ethics, and first-hand chiseling of reality. Under

the light of art, Song Sanghee reveals the darkest continent that our society

has thus far refused to face.