Gerhard Richter once said, “I

find many amateur photos better than the best Cézanne.”1) By “better,” Richter

is not simply comparing the representational capability of photography to that

of painting. This is because photography’s power to demonstrate and extrapolate

reality cannot match that of painting. However, Richter used the photographs as

mnemonics instead of representations of facts: a source of memory images. Many

figurative paintings today use photographs as esquisses. The power of

photography has understandably replaced the visual frames through which we view

the world, and the world itself has taken on a ‘photographic face,’ as

Siegfried Krakauer has put it. The camera has become our eyes, and “our own

sensorium, memory, and unconscious have become, at least in part,

‘photogenic.’”2) In the imagery of contemporary art, photography has become a

new paradigm, emerging as a photogenic world in and of itself, which is more

than just a sketch for a fixed composition to be transferred to a two-dimensional

plane. Miryu Yoon’s paintings of figures are also based on photographs of her

acquaintances taken by the artist herself. Yet, where does the photogenic

pleasure and vibrancy of Yoon’s figure paintings come from? Do they emerge from

the bold deviations that transformed the photographic image into a refined

“composition of color planes” and “lively brushstrokes with a pace”?3)

Since her ‘Dripping Wet’ series

in 2021, Yoon has been inviting acquaintances to perform the configurations and

characters she has created, capturing the scenes in photographs and

transferring them to canvas. She has stated that the figures in her paintings

are “intermediaries to visually embody the sensations and images” in her mind

as well as “alibis for painterly experiments and events.”4) Since the

identities of these individuals, who are often the artist's family, friends,

and acquaintances, are unknown to the viewers, the viewers do not derive any

pleasure, empathy, or faint memories from the portrayed figures themselves. As

such, each portrait of someone constitutes a personal phenomenology. This is

why Barthes argued that sometimes a photograph might “[say] nothing else” and

it is this banality of photography that is its very ‘incapacity’.5)

With these figures that do not

tell the viewer anything as an alibi, the artist creates a phenomenology of

light on canvas. The work of translating the light, shadows, and reflections of

water in natural light into paint and brushstrokes is obviously related to

optical visuality. In a sense, it has to do with the objects, the fleeting

light, and the world of shimmering and reflections that the

impressionist/neo-impressionist painters were drawn to, coupled with the

development of the optical medium of photography. However, the play of light in

Yoon’s paintings cannot merely be regarded as an optical curiosity or painterly

experimentation itself. This is because, within the reflections and ripples of

light and water that the artist captures on canvas, it is the mood of the

subject that emerges photogenically. What is this mood then? We often look at a

photo of someone and say, “This looks like you,” or “This doesn’t seem like

you,” according to their facial expressions, body language, and color tone.

What we seek to capture in the precise representational capacity of photography

is not so much the empirical facts but the mood of the ‘you’ that I know and

the resemblance to the you that I ‘know.’ It is this resemblance that is most

apparent in Yoon’s paintings, and the subjects in her photographs are mere

models acting out that resemblance. In this way, Yoon’s figure paintings are an

intriguing display of the sensorial displacement of the ‘portrait,’ traversing

painting and photography.

Miryu Yoon says that she pays

attention to how the model reacts and performs during the shooting and how

different images are created as they perform their roles. A close look reveals

that the figures transferred to canvas often deviate from the perfect ‘pose.’

It is not the pose of the figure that attracts the eye, but rather the

unexpectedness of the reflective environment, such as light, water, and

mirrors. In particular, the lush, intense contrasts created where light and

water meet hair, body contours, and the wrinkles of clothing covertly

demonstrate the artist’s obsession with the play of the unexpected. “Textiles

are especially attractive!”6) Yoon foregrounds the texture of skin or fabrics

as they take on different hues depending on the light, stretch out with water,

or turn silky and glossy. It is as if the artist is telling us that these

details and surfaces define the elements of her paintings; these are the places

where the meaning of the figures emerges, and they are the new boundaries. The

sparkling and splattering shimmers of water and light serve as a surface in

this sense, transforming the shapes of figures and creating a kind of mood,

which creates a distinctive photogenic effect. This might be the very source of

the vibrancy in Yoon's paintings. It is akin to compressing the ‘Live Photo’

mode7) of a photograph, which exists outside of staged settings, onto the

canvas.

Above all, the photogenic in

Yoon’s paintings connects with the syntax of the iPhone camera, and this syntax

of photography is embedded in the very DNA of contemporary digital imagery. It

determines which moments in our daily lives are worth capturing, which images

make the moment dramatic, and which are worth carrying with us for years to

come. Its syntax is not a matter of personal preference, but a sensory backbone

that synchronizes with the aesthetics of a generation. The same can be true for

the ‘Burst Mode’. Her series such as ‘Wondering How Things Change’ (2022), ‘Naked

Flames’ 1-5 (2023), and ‘Want to Touch the Other Side’ (2024), presented in the

current exhibition, are based on images taken in ‘Burst Mode’. These paintings

epitomize the sensation of flipping through photos taken in ‘Burst Mode’. Above

all, ‘Burst Mode’ offsets a sense of awkwardness that comes from fixed poses,

underscoring the raw emotion and mood of the subject and capturing it with more

precision than our own senses. ‘Burst Mode’ also makes it impossible for us to

choose a single favorite scene, alleviating the desire and dilemma of arriving

at this impossibility of making any decision. When the picture is enlarged onto

canvas, it sometimes functions like a screen, highlighting the ability of the

‘Burst Mode’ to easily convert to GIFs (animated images). The sense of

difference that emerges in this chain of images is, as critic Hyejin Moon

points out, reminiscent of Barthe’s notion of ‘the third meaning.’8) It is not

a property of the single photographic image on its own; it is a kind of

‘punctum’ generated by a paused image in a chain of moving scenes. Barthes said

that in that moment of pause emerges a vague, blunt meaning that is neither

about the plot of a story nor the symbolic meaning of an image.9) In Yoon’s

paintings, such meaning erupts from the expressions and gazes of the female

figures, especially those captured in ‘Burst Mode’, and from the distinctive

hues and shimmers that seem to set their faces and eyes on fire.

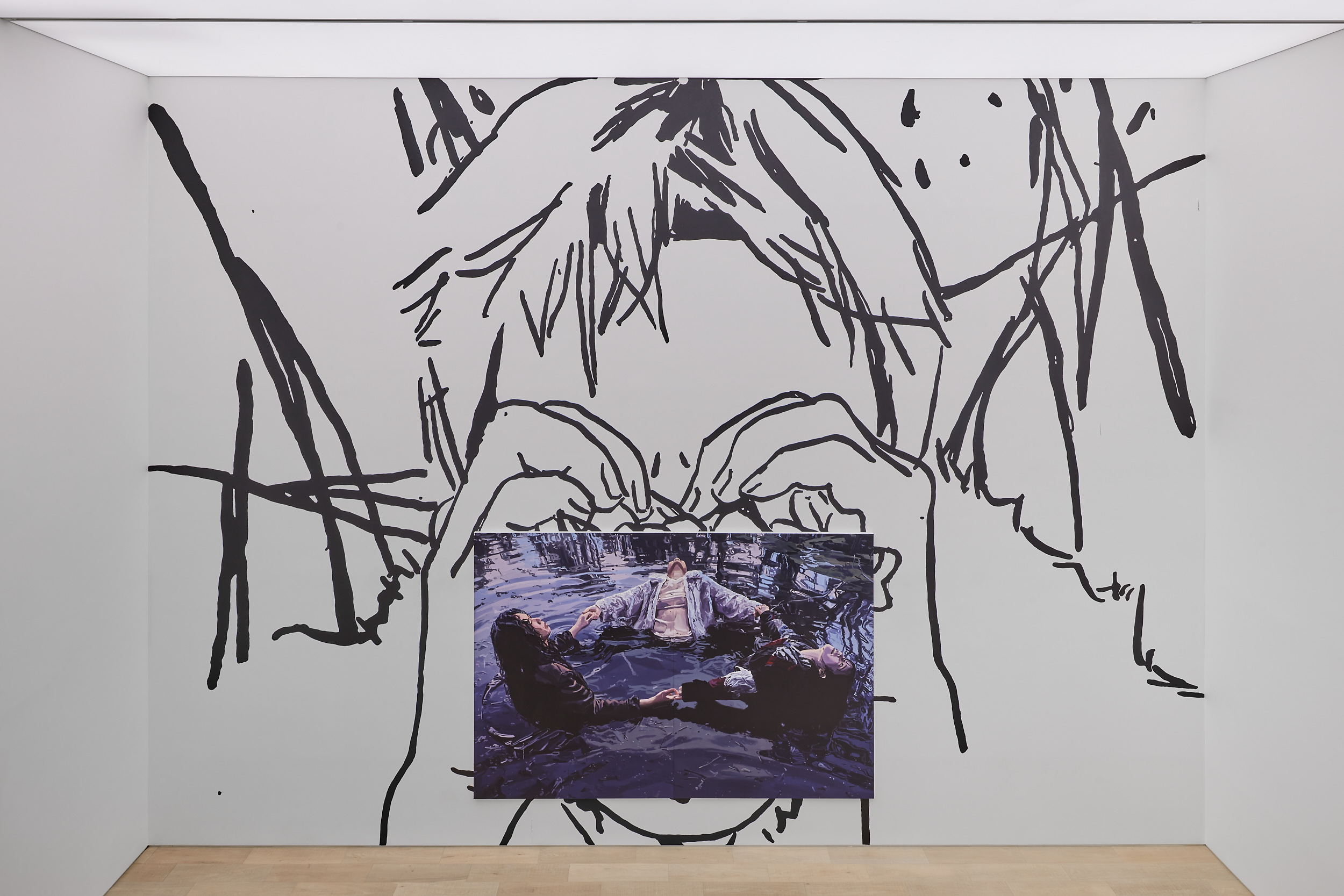

However, the emotion or the mood

of these paused images seems to emerge, paradoxically, from the intensity of

their sequence, responding to the strength of the narrative impulse that builds

a more vigorous tension. In her solo exhibition, 《Do Wetlands Scare You?》, Yoon uses the

wetlands as a symbolic space to present a series of pseudo-mythological scenes

featuring three women. By further expanding on the scenario-driven nature of

her previous exhibition 《Pyromaniac》 (2023), where she metaphorically described ‘igniting fiction’, the

artist has created a series of impressive sequences. The artist took the

photographs in the wetlands around the SeMA Nanji Residency, where she is

currently working. The area is adjacent to Han River Park, yet largely

uninhabited. Against the backdrop of this wetland, the artist created cinematic

scenes inspired by Northern European myths of witches of the wetlands. The

figures in the paintings are drawn from eerie mythological tales, such as the

Russian water nymph Rusalka or the Nordic mermaids. However, with no concrete

source or description, the three figures only evoke the personality and actions

of certain characters, described as “a curious, overbearing prankster,” “a girl

unconcerned with destruction and redemption,” or “a shaman with a cynical

aura.” Whereas Yoon’s figure paintings in the past have focused on the

directivity of granular words as emotional states—determination, jitter,

chilly, nonchalant, withstanding, among others—that can be translated from

certain images, these paintings take the form of more narrative, densely woven

phrases. Furthermore, while past paintings described the vibrant and lively

magical surface achieved through the gleam and vivacity of pigments, the light

of paint and texture in new works evoke a sinister, murky quality, suggesting a

viscous fluidity akin to a dark magical atmosphere.

The figures of three witches,

reminding us of the Three Graces in the wetlands, culminate in the ritualistic

scene of Circle for the New Moon (2024) or the depiction of

complicity in The Difference Was Clear to Us but You (2024).

These scenes evoke the unnerving belligerence and manic glee of witches often

depicted in folklore, grim fairy tales, and fantasy novels. However, each

painting is punctuated by dark yet cold light, along with opaque and disparate

emotions. There are gazes that hold us in place like water ghosts, light

reflections reminiscent of white nights or dusky evenings. They move through

the canvas like undercurrents beneath the surface of figures and situations.

Yoon’s latest works are imbued with this eerie, uncanny feminine jouissance.

Mark Fisher argued that the eerie as the uncanny is found “more readily in

landscapes partially emptied of the human.”10) Therefore, such uncanniness

leads us to ask what happened, what is no longer there, and what it has to do

with existence. They are paintings in which absent episodes, ghostly beings,

and narratives that exist only as scenes appear as the ‘photogenic’ that

illuminates like moonlight. This photographic quality invites us to be

detectives, not consumers of images.