‘Sadang’

means shrine but with a nod to the continuous, the title ‘Sadang B’ replaces a

possible sense of the ultimate icon. The suggestion here is that Young In does

not wish her exhibition to aim to function as the end of the subject or

journey, but to be instead a mere participant in a series of actively asked

questions. ‘Sadang B’ implies that there is also an A, a C, and perhaps even a

plan D. This shrine is not the only shrine, and B is part of a range of

categorization. This title immediately implies another, perhaps parallel,

order, process and rationale. Life, goes on, it seems, elsewhere.

As

a highly accomplished artist, Young In uses whatever medium seems right and

relevant for whatever she needs to say at any particular time. 《Sadang B》 is an exhibition of

three works, with three types of moment, action, and ritual, taking place

in three different sections of the gallery. The artist’s characteristically

generous repertoire is represented here, in part, by audience involvement with

different forms of movement to improvised music, sewn objects, recorded bird

sound, and choreographed movement.

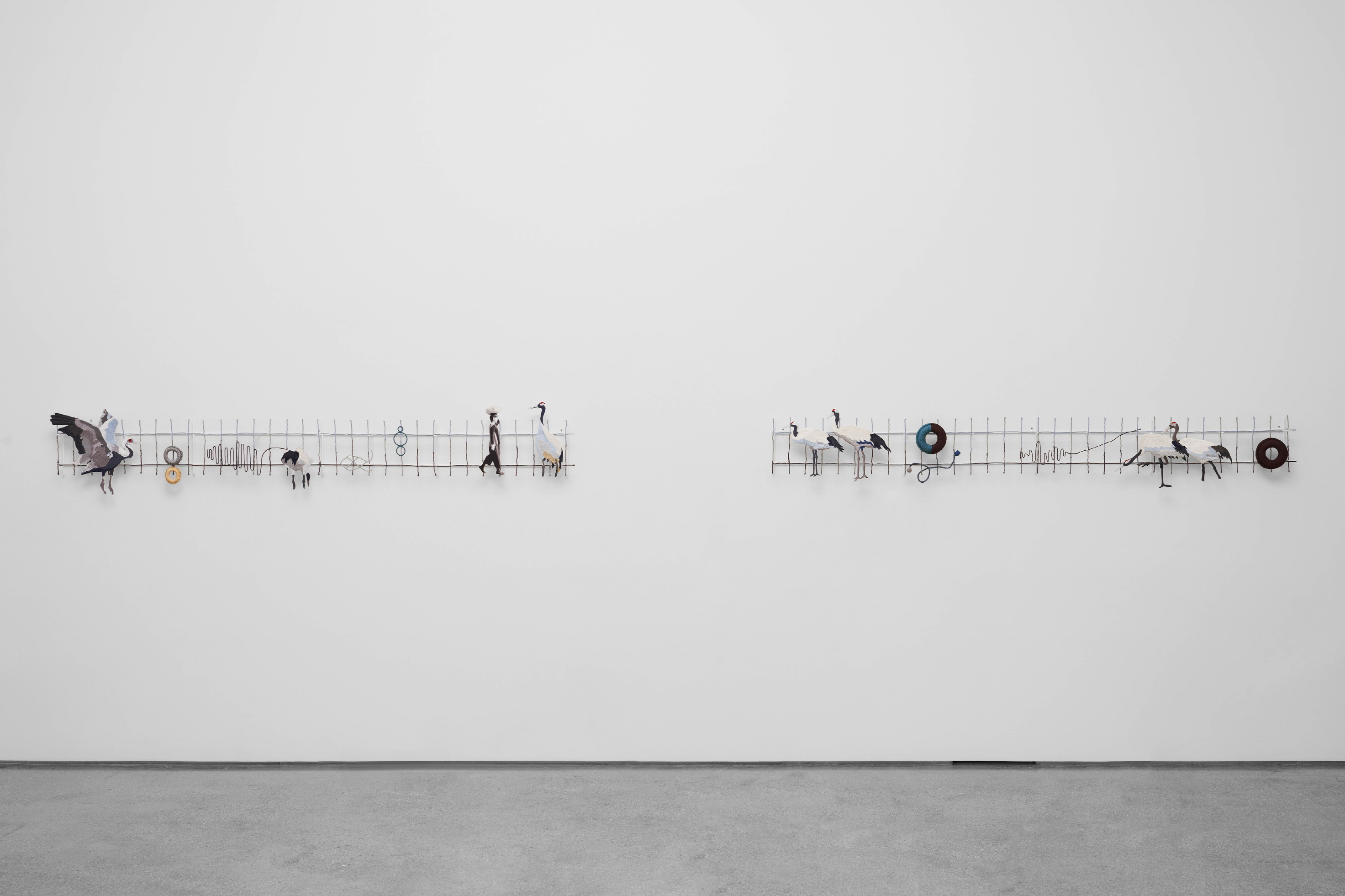

The

notion of the permanent is challenged by the temporary. A range of

embroidery, collage, tapestry and drawing move from the fabulous to the

perfunctory with work that mimics a change in a skyline, for instance, as it

traces the outline of figures, buildings, trees and crossroads to become

imbedded in a two-dimensional horizon. Often, once a line emerges and takes its

role here, the everyday inevitably can be elevated into much greater theatre,

and vice versa. The artist traces, literally, old photographs in her

recent works, and tried to touch some of the shifts and disruptions in the

history of Korea over the last thirty years.

Utilizing the cultural and

folkloric iconography of Korean culture, the artist hopes to forensically

unearth something that is significant and yet perhaps unclear. A

compression of space and experience runs alongside the visualization of past

and current struggles in her native Seoul. For the artist, any rise in

simplistic characterisation means that a wide-open pride in National

identity has to be feared. Her process of sorting through found images and

museum photo archives mixes with childhood, adolescent, and student memories to

create a fundamental, and multilayered process of questioning for Young In, who

now lives in England.

With

sinister tweeting on one side, and simple ominous shadow on the other, the

first piece, To Paint the Portrait of a Bird shows the

artist seeming to already question notions of freedom. Who can be free to do

whatever he, she or they, wants? A loud tweeting in this huge bird cage, and

the implication is that you cannot get out, sits with fantastic heraldic

embroidery, mustered and gathered together to conjure the most convincing

equivalent of a series of coats of arms. This work, an engagement with belief,

also draws a parallel with a hierarchy of species, of assumed differences

between the animal or bird kingdom, for instance, and therefore the inevitable

conclusion about any Nationalist thought that places human over human.

Unconsciously border free, however, the birds which are sometimes outlined as

shallow sewn objects, are brought together along with real shadows. Redolent of

many cultures, birds from everywhere; penguins, ducks, and flamingos, seem

to represent different countries to characterize local as well as other places

and climates. Held on to, sewn or tacked into simple, decorous,

delicate traditional icons, these apparently direct metaphors show the artist

appearing to question this or any hierarchy, aware, anyway, that birds are

capable of flying further and longer than any high-powered business woman or

man.

There

is no innocence anywhere and Young In trails, or sprinkles the subject of

destruction and preservation, taste, history, and identity to run alongside and

through her work. Questions about value, the role, absorption and rejection of

cultural history prevail. What about the control of grand imperial vistas and

colonial buildings? Should they be bought down or left to be overtaken by new

histories?

Young In talks about being disturbed, for example, by the

full-scale demolition of the Japanese General Government Building, a

Colonial building in Seoul. This place had great significance for her as a

child because of the ‘lovely’ garden, in part. The government said the building

‘blocked the energy of the Nation’, the public agreed. It is impossible

to argue about such a representation of a subjugation to an external power, and

it was demolished in 1996.

Although

of great significance, a shrine is still a construction. The role of the

audience is key in that each spectator is identified with, a participant in,

the artist’s active, three dimensional, questioning of change. The significance

of the religious relic, itself a matter of belief, runs alongside the whole

process of the making and perpetuating of art. It runs beside the fact that

value, again so nebulous, lies not in the financial value of a material used,

and in a different significance. Young In is playing with a whole

building, and then destroying belief.

Her work deals with manifestations of a

recent past, the city outline that sways the way that art tells truth and lies

at the same time. She plays with the way that history elevates elements, only

to dash them because of a change in significance and circumstance. One person’s

hero is another person’s personification of hell, after all, and Young In works

between the construction of meaning in an artistic sense and the significance

of memorialisation. From the outside she observes a country that seems to try

to act tougher like a family putting the right foot forward and down.

At

the beginning of the exhibition the audience starts with active

involvement. Young In makes a shrine that has the depth, intensity and abstract

use of a Confucian ancestral ceremony carried out by sons of the family while

the women wait outside. She introduces an underlying theme to the exhibition

which is very much about the way that women are meant to behave. So the

audience starts out at the beginning in a cage, albeit with the ability to walk

through.

The audience is implicated, surrounded and involved in a way it cannot

avoid, and then, next door, the same member of the audience becomes a

spectator, listening through speakers as well as headphones. The second work, The

White Mask is straight forward in its delivery but complex in its

relation to the artist who asked, or perhaps instructed, musicians, from the

celebrated Notes Inégales group in London to follow instructions. She asked

them to play their classical instruments with their total personification, or

animalization in mind.

They become or became creatures and the result is clear,

in a way. These musicians practice the deepest, frankest, most creative level

of collaborative improvisation and music making. It was said at the time ‘but

we are animals already.’ Young In is an accomplished musician, and much of her

recent work, Prayers (2017) and Looking Down from

the Sky (2017) involves the making and performing of scores often

extrapolated from the outline of a historical photograph of Seoul.

Un-Splitting

consists in part of a performance projected onto the wall and an embroidered

label announcing the schedule of further performances at unspecified spots in

the lobby and outside the gallery. The performances are a response to the

repeated movement of women working in factories found in photographs by

the artist. Performers act out instructions to women factory workers, obeyed

not so long ago. Studying images, like many she uses, found in the Seoul

Museum of History, Young In works with performers and a choreographer to

construct movement, bringing in the actions of perhaps even less ‘valuable’

animals and birds as well as that of women at work in factories.

She says she

actually senses women’s fight to address the idea that their labour is ‘lower’

than that of a man. Movement brings everything together in an attempt to see if

by perhaps looking somewhere else, looking down, or up, and across

species, there might be a better way to communicate, and therefore

exist. A collective movement of the combined body of performers, some

professional, some volunteers, is powerful and touching. Having advertised and

recruited online, Young In has brought contemporary dancers, theatre

actors, members of the general public and university and high school students

together.

Divided into two groups, each of six to seven performers, they

reinforce apart from everything else the fact that women workers were expected

to smile all the time. Workers were called by numbers not names, as well,

not long ago; perhaps they still are? Each piece is different but

connected. The tone the performers take is democratic but also influenced by

whoever and what else is there. Performances programmed elsewhere other than in

the gallery bring the work back to places Young In spent time in as a child,

and where she now engages as an artist.

Attempting

a complex but apparently sound method for renegotiating not only the

representation, but the effect, of reality, Young In’s work is based very much

around a precarious relationship to the past, about the way that it can be

re-interpreted in different ways in terms of what is being looked at,

preserved, re-considered, and surveyed in both pictorial and emotional

terms. Aiming for a new way to communicate she is able to use what is out

there, to transform, in terms of function, whatever it is that she traces and

identifies.

The outline of a horizon in a photograph, for instance, is used to

write a score; the sewing machine turns into a musical

instrument; the outline of a sewn, projected, drawn or collaged bird

becomes the harbinger of good and bad, as well as the representation of trapped

desire in a confident, heartening, but open contemplation of the design of

political will.