According

to Young In Hong, her work is about seeking ways in which the concept of

‘equality’ can be questioned and putting them into practice through art. These

words might remind one of sociopolitical activist art, which dominated the art

scene of the 1980s and 1990s. In terms of subject matter, most of her works

deal with those people whom society regards as minorities, and in terms of

medium she often uses methods that are not usually associated with high art

such as sewing and embroidery.

Hong’s approach to the idea of equality is,

however, considerably different from the familiar and typical modes of tackling

sociopolitical issues. The voices that speak of what is marginal are easily

subject to the danger of falling prey to an oppositional dichotomy. The label

or category of minority itself is an obvious sign of approving the existing

hierarchy between the central and the marginal, and the efforts to defend the

rights of the marginal frequently turns into the struggle for recognition to

replace the central with the marginal. How can we pay attention to those who

are marginalized without categorizing them as a specific group or embrace the

marginal without differentiating or objectifying them? Hong’s practice presents

us with a small suggestion as to a possible answer to this difficult question.

There

are two points for an artist to consider if s/he intends to embody equality in

a visual language: one is a content-oriented embodiment using it as a subject;

the other is to incorporate it into the production process or form. The former

is the relatively easier and general approach, but it has an unavoidable

limitation in that content and medium work separately. It is at this very point

that Hong’s method stands out: in her work, not only the content but the

process and the resulting body (form) likewise defy the established hierarchy,

quietly but clearly. Consequently, equality operates and is achieved with

respect to both content and form, namely, both internally and externally.

The

most conspicuous feature is the use of needlework or a sewing machine. The

low-wage labor of sewing, which is done largely by female factory workers in

the region of Asia, is a good referent for otherness in terms of both gender

and class. In fact, the artist learned this skill from the seamstresses working

at Dongdaemun Clothing Market. Yet in Hong’s work sewing is employed to reflect

neither femininity or Asianness nor a subcultural identity.

The intent behind

her utilization of sewing is not targeted on the portrayal of otherness itself

but is to reveal the boundaries of which we have never been aware. An example

would be the criteria for the category of high art. By adopting the element of

needlework, which is excluded from the realm of fine arts as craftwork, in

realizing the conceptual and intellectual content of the work, the artist blurs

the divisions within the genre of high art and brings together differences. The

fact that it not only criticizes the institution internal to art but also that

it necessarily corresponds to the content of the work attests to the very depth

of Hong’s work.

For instance, Burning Love (2014) is an

embroidery work of the spectacular scene of the candlelight vigil protesting

against the import of U. S. beef in May 2008, which deals with the affections

of ordinary citizens (especially teenage girls) who are not the protagonists of

the official history of the event. The form of embroidery that requires the

honest labor of making one stich at a time is an adequate medium to cast light

on every individual who gathered in the streets voluntarily. Here, a large

number of people participating in the protests are referred to not as members

of a group like a race or a nationality but an assembly of different

individuals, that is, a multitude. The small but passionate aspirations of each

participant are stitched with much care, manifesting themselves as proud pages

of history as a galaxy with a plethora of stars.

On

the other hand, in her performance work, another medium for the investigation

of the keyword of equality, social issues and fine art elements are more

actively interlaced with one another. Owing to its attributes of chance and

immateriality, performance can easily cast off the limitations of originality

and uniqueness that works in the objet format have difficulty escaping from —

even when using unconventional means such as sewing.

Furthermore, the control

of the work can be more impeded by the voluntary participation of the general

public than when carried out by casted performers. 5100: Pentagon

(2014), premiered at the Gwangju Biennale, is a performance piece where the

volunteer audience performs the choreography inspired by the May 18 Gwangju

Uprising. Participants vary every time, and so does the performance. As various

groups of people from outside of the art scene act as subjects in creating a

work of art, the performance opens up a small interstice in the closed category

of the museum. As each of today’s different others ruminates on the painful

history of Gwangju in his/her own way, they form a small temporary and loose

solidarity. These ripples wipe out the border between art and non-art and what

is experienced here lingers on in the minds of the participants.

In

her recent work, Prayers (2017), embroidery and performance

integrate. Hong transcribed a part of a news photo of a landscape of postwar

Korea onto fabric in embroidery and played this like a “graphic score.” Her

work of this method — also called “photo-score” — is the act of rewriting the

mainstream history of Korea, which is South Korea-oriented and male-dominated.

The trivial details irrelevant to the imparting of the message of the news

photo are part of the unrecorded history. By erasing the center and slightly

raising the details, the artist transposes the center of gravity of the

historical narrative. The history, primarily rewritten through the artist’s

embroidery, becomes a music score and once again undergoes a reversal. Even if

there is just one score, its interpretation divides into as many as the number

of the players. Each performer plays differently and each performance is

thereupon a version of history written by an individual.

As my experience and

yours are different, the year 2019 as I remember it is inevitably different

from the way you remember 2019. Accordingly, how inadequate must the mainstream

history be that leaves aside all of these countless memories. Its

interpretation varies depending on the performer, and those interpretations

split into ceaseless derivative versions, muddling up you and me, man and

woman, and Korea and other nations. In the middle of this, the boundaries

between the artist and the audience and between art and society are blurred. A

cheerful stage of hybridity where the history I wrote and the history you wrote

coexist and harmonize; this is the way Hong sees difference, as it is the hope

that she harbors.

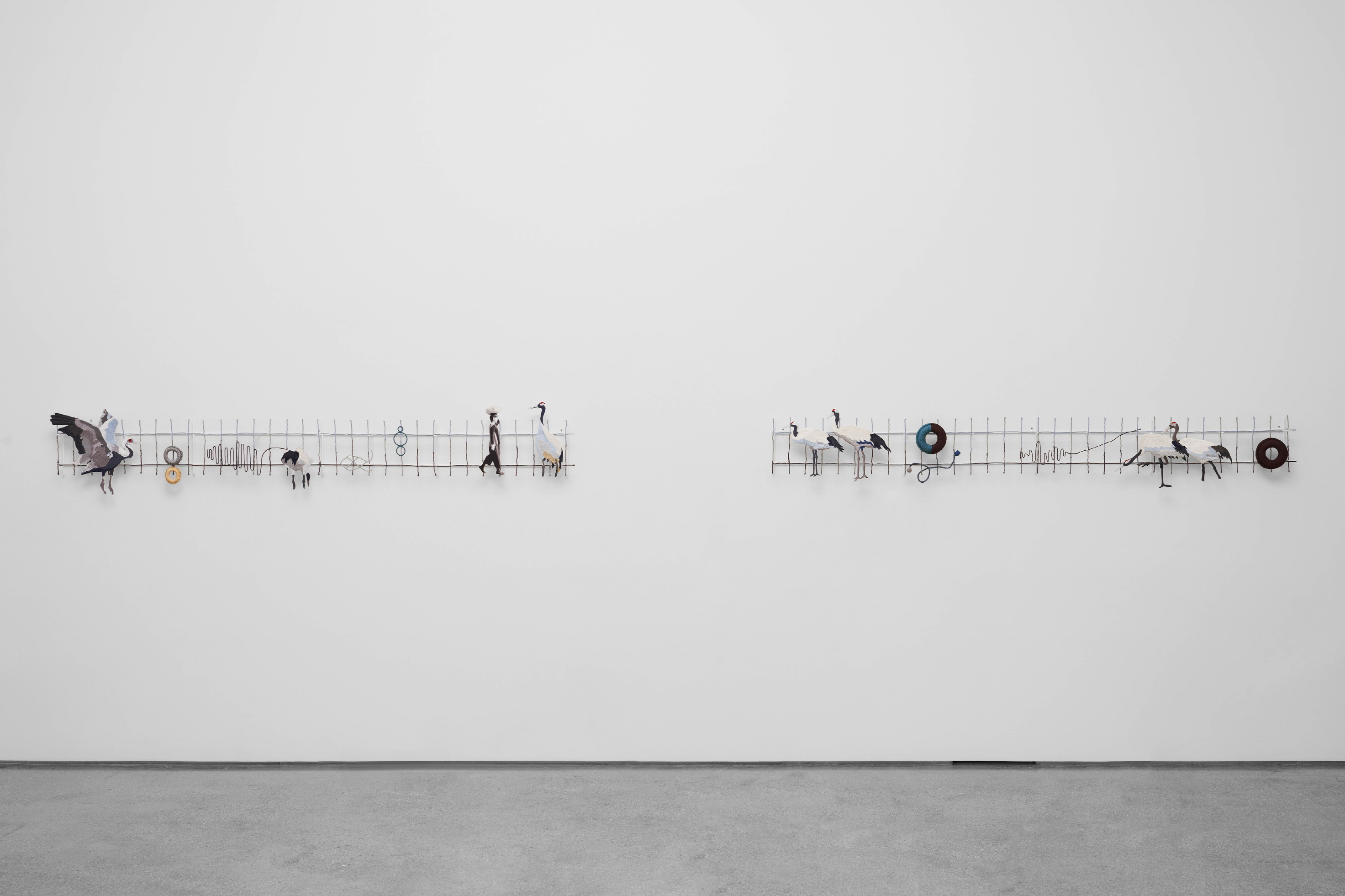

In

the 《Korean Artist Prize 2019》 exhibition, Hong extends the concept of equality beyond humans to

apply to non-human agents. Comprised of three new works, Sadang B

(2019) attempts to rethink the dominant (human)-oriented viewpoint by

positioning birds and animals as subjects. Here, one is driven to be confronted

with a strange unfamiliarity: the ironic situation in which viewers are placed

inside the birdcage looking out to the space where birds are; the

improvisational performance by the musicians who are trying hard to become

animals; the dance where performers mimic how females labor and how animals

move.

This discomfort is, in fact, a necessary emotion. For it allows one to

realize how difficult it is to become the other on the one hand and on the

other points out the value of the attempt to try to walk in the shoes of the

weak, even though it would never come to pass. Hong pursues a delicate quest

for a certain balance that is very particular and yet universal and individual

and yet collective, and it is hoped that this quest of the artist is shared

with many more people. In South Korea where dichotomous stances and loud voices

are dominant, aimless resistance, non-group identified subjects, and

non-divisive coexistence are such rare and scarce values. It is hoped that this

exhibition will be an opportunity to witness the quiet permeation of its

genuine radicality into the mind of each viewer.