Jung’s

work cannot be summarized as a critique of the contradictions and harms left

behind by modern ideology in Korean society, nor as socially engaged realism or

activism. This is because he does not have firm faith in the political

authority or ethical imperative of such painting. He clearly respects the cause

of the student movement that devoted itself to democratization and agrees with

the role of Minjung Art as a form of political action. However, for his

generation—who grew up in a depoliticized era, enjoying free culture amid

economic prosperity—the student movement was not a struggle but rather an ethic

grounded in “affection for others, consideration for the weak, and universal

humanism.”⁸

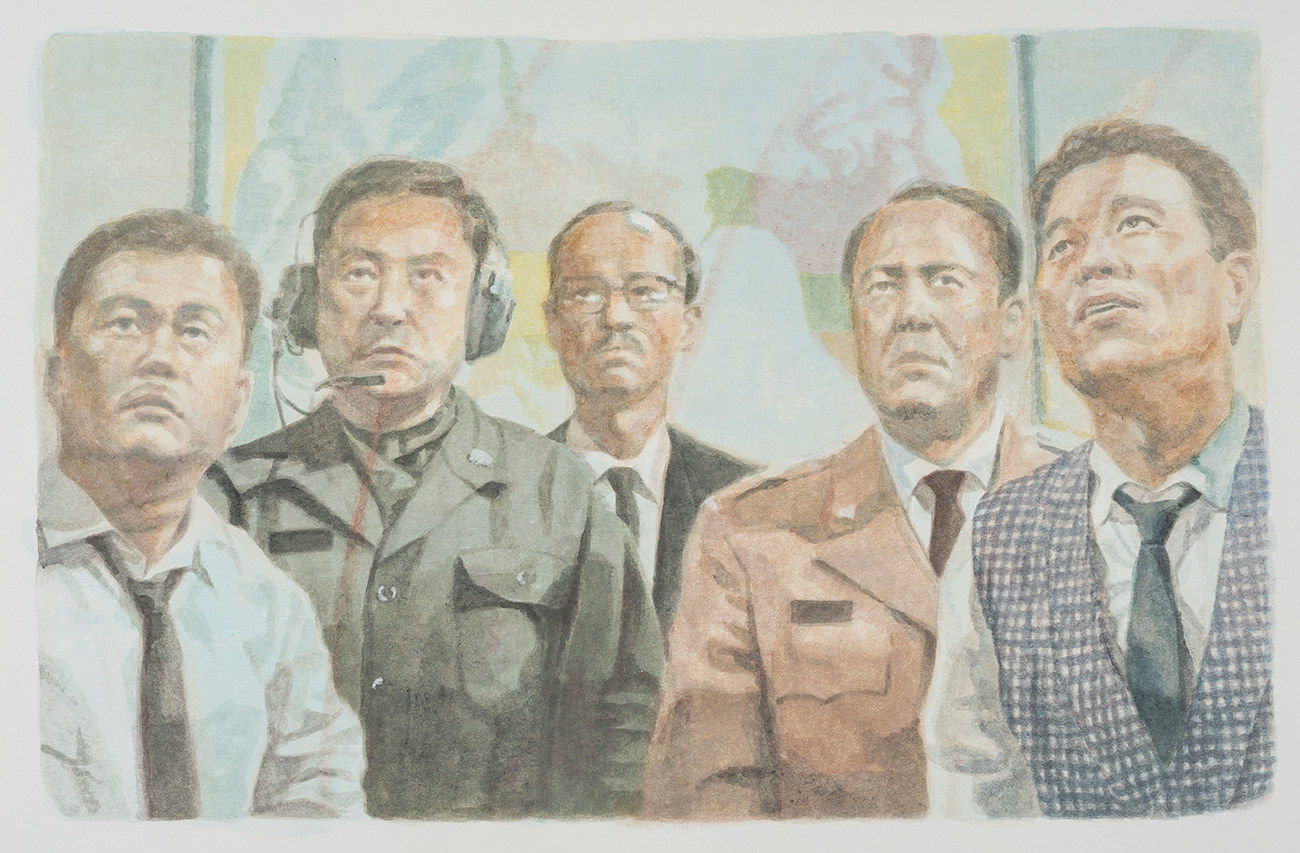

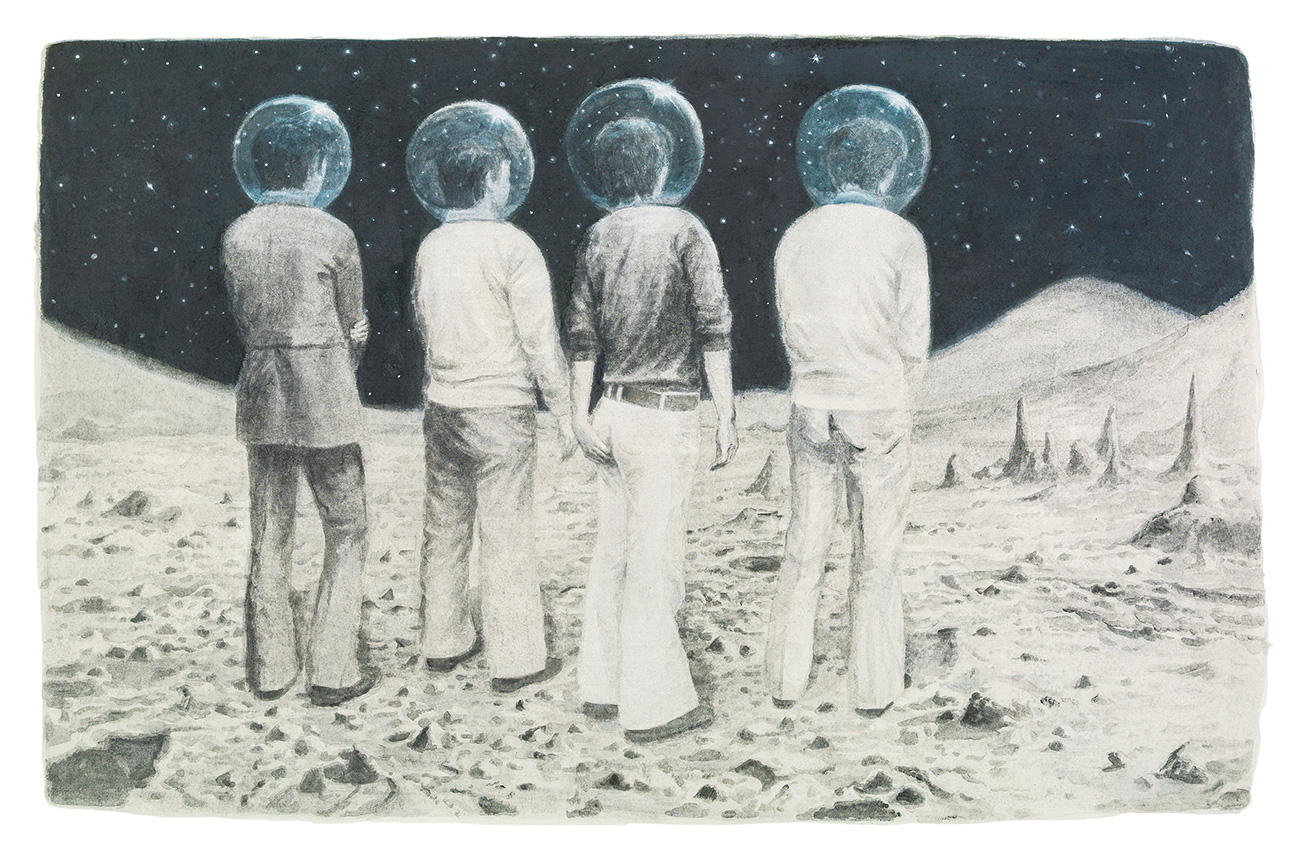

As

a result, on the uniformly sized surfaces of the “archive paintings,”

revolutionary flames and melodramatic film heroines coexist as equivalent

images. All of these images, already circulating within the framework of

representation, never present reality or the real itself. Ultimately, in a

media society where everything—regardless of historical weight or personal

significance—is transformed into surface images that circulate, are consumed,

and eventually disappear in rapid cycles, Jung chooses surrender over struggle.

His paintings do not instruct viewers by critically exposing the hypocrisy or

falsity of images. The refusal to teach anything—this is the ethical mode of

reality presented by 《Days of Dust》.

¹

Michel Foucault elaborated on the concept of heterotopia through a series of

publications beginning with his lecture “Of Other Spaces,” delivered in March

1967 at the Cercle d’Études Architecturales in Paris, and culminating in The

Order of Things. See Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and

Heterotopias,” Architecture / Mouvement / Continuité (October,

1984), trans. Jay Miskowiec. For a collection of Foucault’s writings on

heterotopia, see Heterotopia, by Michel Foucault, trans.

Sang-gil Lee (Munhakgwa Jiseongsa, 2014).

² Sang-jun Park, “The 21st Century, Korea, and SF,” Today’s

Literary Criticism, no. 59 (2005), p. 47.

³ Han-woo Park, “Elon Musk and the Crying Generation of the 1970s in

Korea,” Daegu Newspaper (January 5, 2022). From

this perspective, Jung’s situation—having written extensively on the blog

Egloos since its launch in 2003, only to lose his platform following the

service’s closure in early 2023—resembles the forced eviction of residents when

an old apartment building faces demolition, reenacted in virtual space.

⁴ 《Cheonggyecheon Machinery Tool Market: From

Fish-shaped Waffle Molds to Artificial Satellites》

(Cheonggyecheon Museum, December 10, 2021–April 10, 2022).

⁵

Jeonghwa Ryu, Jehee Kim, Hyejeong Park, Chaejeong Song, and Yunji Jo, interview

with Jaeho Jung, October 3, 2022.

⁶

Jaeho Jung, “Notes for a Lecture_Artist’s Notes Left on Egloos” (March 19,

2023).

⁷

Jaeho Jung, “Youthhood_Artist’s Notes Left on Egloos” (May 17, 2016).

⁸

Jaeho Jung, “Political Lessons at Art School_Artist’s Notes Left on Egloos”

(May 31, 2006).