“In

schematized time, nothing really new can emerge—everything is always-already

there, and merely deploys its inherent potential... We are dealing here with

another temporality, the temporality of freedom, of a radical rupture in the

chain of (natural and/or social) causality.”

—Slavoj Žižek (1949–)

1. Introduction

Hugging

a stuffed Minnie Mouse without eyes, a woman is sitting on the toilet with her

closed eyelids painted over with the eyes of Minnie Mouse. Could a photograph

of this woman be called art? If so, what would be the aesthetical value that

we, the viewers, should recognize? If a framed kitsch landscape painting,

purchased from a decorative painting shop in the Samgakji area in Seoul, is

split in half with a panel with horizontal strips inserted in between, would

such be considered a recycled object or a challenge against stereotypical art?

A little boy is walking down the street when he is eaten alive by a wolf, so

his grandmother, who is well versed in fairytales, goes into the wolf’s stomach

and is reborn as a little girl, and then meets Prince Charming, and so on and

so forth. So goes one endless, nonsensical tale. By exhibiting a piece at an

art gallery that forces visitors to listen to such a continuous loop of a

hodgepodge or re-creation of stories that we’ve all heard at one time or

another, what sort of experience is the artist trying to convey? Iconographic

figures of gods and saints including Jesus, the Virgin Mary, Buddha, Confucius,

Lao Zi and Muhammad are dismantled into separate groups of body parts such as

eyes, noses, mouths, face shapes, left and right, and upper and lower bodies,

etc. Then a public survey asks people to pick their favorite part from each

group, and the features with the greatest rating are put together to create a

new idol—what sort of absoluteness would such a statue symbolize? Would it be a

jumbled monstrosity of a certain religion or a great mind? Or, perhaps, could

it be that the sculpture is the most humane, and simultaneously, the most ideal

icon of reality that cannot represent any one specific creed or philosophy?

The

sudden profusion of questions above has probably left you confused. Or, you

might have the impression that it was all just a muddle of miscellaneous,

convoluted and disparate items. And some others might think that more important

than the questions themselves is what they present as their subject. I agree.

Without doubt, the examples I rambled on about are immensely more important

than the questions I raised after each wordy description. However, those

examples are by nature impossible to sum up neatly with clear simple words,

delivering precise judgments based on sophisticated art criticism, so I had no

choice but to relate them with confusing terms and then conclude with

questions.

The

examples constitute Yeesookyung’s art. That is, they are part of Yee’s oeuvre,

as exhibited from the early 1990s to this day in the early 2010s, and it is my

task in this article to illuminate Yee’s art from the perspective of an art

critic. Thus, my very first question has now been answered. That is, the

snapshot of the woman with painted-on eyes in the style of a cartoon mouse, and

all the other pieces above are already indeed ‘art.’ And yet, there is a lack

of consensus as to what aesthetic qualities such images have held for us, how

to appreciate the pieces or whether they can be read into critically. Moreover,

when art is pursued and created in the manner of the abovementioned examples by

Yee, we lack ‘definitive answers’ to the particular sources and mechanisms of

originality, or to what we, as viewers, can enjoy and in what fashion. In all

likelihood, this article will fail to offset such a deficiency or uncertainty

of aestheticism and criticism. But it can at least unfold the various questions

that Yee’s art induces us to ask, and address a host of issues that can

‘provide answers’ to those questions, focusing on specific works by the artist.

Given that she built her oeuvre for a considerable period of twenty years or

so, during which she presented multifarious art practice using a myriad of

materials, the spectrum of such questions and issues is also as wide and

colorful.

2. Minnie Mouse, Going Beyond ‘Preferring Not To’

Beginning

in the early 1990s, Yeesookyung has communicated in a visual language that

‘defied the mainstream’ art of the time, presenting works that are physical

manifestations of this language through various media. That is, rather than

allowing her work to be incorporated into existing frames of art, this artist

has been manifesting an experimental and unfamiliar aesthetic with a novel

form, expression methodology, technique and utilization of medium that

corresponds with each particular piece. Therefore, if we were to evaluate Yee’s

art as being ‘experimental,’ the implication of it would be that things which

have not yet secured a position in terms of art history, or have yet to become

conventional, can still be considered ‘art.’

Such

an experimental piece, however, can invoke feelings of unfamiliarity and

discomfort in the common viewer aside from the connoisseurs of contemporary art

who are always prepared to recognize anything as art. Or it may cause confusion

or even elude the mind altogether without ever being recognized as a work of

art because it is unlike any definition of art, aesthetic consciousness or

artistic experience that has been registered in the viewer’s cognitive or

sensorial memories. In reality, this conservative tendency in the general

public’s capacity to appreciate art suppresses the creativity of many artists

whether it be on a psychological or systematic level. For instance, the artist

may fear that his/her art will be shunned by people who prefer conventional

art, or he/she may set internal rules so that the work is not excluded from

exhibitions or projects held by galleries that are most concerned about public

response and monetary profit. This is why a great many artists continue to

produce art that is far from anti-aesthetic or avant-garde, but is a bit cliché

and somewhat stereotypical. Interestingly, however, the history of contemporary

art was able to arrive at its current state through the practice of

anti-aesthetics and the avant-garde. You don’t have to be an expert to know

how, through the ‘ready-mades’ of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), art was able to

expand its territory to include not only the product of an artist’s manual

labor, but also a proposal of an aesthetic concept. Later, along with the ‘silkscreen

paintings’ by Andy Warhol (1928–1987), contemporary art was able to pioneer the

domain of ‘Pop Art,’ which blatantly complied with popular culture. In other

words, there exists a history of art as in Duchamp’s notion of art as “a game

between all people of all periods.”

In

that context, experts of contemporary art have always welcomed experimental

attempts in art, and in fact, it would not be an exaggeration to state that

artists learn undiscovered artistic languages in such process. I myself, the

writer of this article, am no exception. I came to understand the significance

of the various forms and properties of art of which I am currently aware and

approve, and have an open attitude towards accepting anything to increase that

diversity with pleasure, in part from the works of artists that posed

challenges to existing art. And of these, Yeesookyung’s art has left me with a

particularly strong impression.

While

I was looking at Yee’s photograph Colorblind test to Blind Minnie

Mouse (1998) in early 1999, I realized that contemporary art

could be something like an event, such as a presentation of an image that

emerges for a fleeting moment in time. The photograph captures a young woman

with eyes painted on her closed eyelids that resemble the plastic eyeballs of

Minnie Mouse, who is the partner to one of the greatest icons of American

popular culture, Mickey Mouse. It comes across as an insignificant mark made by

somebody goofing around like a child with whatever happened to be at hand at

the moment. An image made on the spur of the moment, like the photos we all

take now and then, without much thought, just to have fun. However, I

discovered in that photograph the potential for Korean contemporary art to

become ‘something infinitesimally small, exceptionally frivolous and very

brief.’ At the same time, I concluded that such smallness, frivolity and

transience are sensuous properties that go beyond art as we used to know it,

and have expanded its potential, adding another dimension to its diversity, and

breaking time into smaller units to enrich the experience of art. This was

because from the photograph of the Minnie Mouse woman, I felt that I had a delicate

sensorial experience of a very thin film coating or coming off the human face

and an image over it. And such experience aroused in me a very pleasant and

joyful, yet unfamiliar, artistic awareness. And that is how I came to expect

that the fleeting awareness, or the things that are unfamiliar to numbing

existing thoughts and senses, will become the new characteristic of

contemporary Korean art. The image of Minnie Mouse vanishes from Yee’s face the

moment the makeup is removed. No matter how current photography is in

contemporary art, the snapshot by Yee is extremely modest in comparison to the

spectacular high definition images which we normally call art photography.

However, such transience, simplicity, and above all, the everyday context

illustrated by the artist’s photographs and her strange acts of disguising

offers a breath of fresh air to those who are overexposed to fine art’s

abstract imagery and incoherent meanings. This means that to a viewer whose

training of the senses within existing art has been limited to seriousness,

absolutism and a disregard for time, Yee’s photograph stimulates by trimming

the corners of the senses to facilitate a more detailed and lively sense of

beauty.

The

idea that artwork can disappear leaving just its trace in the physical time

rather than represent impermanence has been given a sensorial form of

expression, becoming today’s happenings, performances, and site-specific art,

etc. In addition, the trend among young artists whose work we can easily come

across is that the artist is someone who entertains through art rather than

being an unaffected agent of creation, and also that the artist’s playground is

not an ideal world of beauty, but a world that becomes filled with everyday

objects and affairs. Here, I am not trying to say that this one photograph

taken by Yee in 1998 was what enabled that kind of art. Such an argument—in

consideration of how Western art diversified since the 1960s, and also given the

few experimental attempts made in Korean art including the area of performance

art from the 1970s to 1980s—is too likely to be erroneous. Being in a position

which demands that I define the special characteristics and mechanisms in Yee’s

art, my intention is to emphasize the fact that her work ran counter to the

mainstream of Korean art in the late 1990s. Yee’s methodology was, in a way, to

proceed by “preferring not to” go in the direction of that stream, moving away

from abstract paintings, away from being tied down by dogmatic messages like

those of the Minjung art movement in the 1980s, and away from conforming to the

pretentious grandeur and purity of modernist art. Such methodology signifies a

euphemistic and passive resistance. However, this resistance ceases to be

passive if such method becomes fused with the property of art of ‘doing

something’, that is, the property of taking existing materials and producing

things with specific form. For instance, one could say that in the 1853

novel Bartleby, the Scrivener by Herman Melville

(1819–1891), the namesake hero employs a resistance mode of ‘not doing,’ while

Yee’s art follows a creation mode of ‘doing something as if not doing

anything.’ If one continues to employ such a mode, the art then acquires a

covert nature as well as a bold individuality.

3. Story of MunKil (long Journey), Imagination of a Folding Fan

Considering

the whole of Yeesookyung’s work, it becomes evident that Yee’s artistic

attitude and experimental acts of creation maintain a consistent flow

throughout the entirety of her work while the individual world of each work is

discontiguous. That is why I consider ‘discontiguity’ and ‘contiguity,’

experimentation and rendered actualization to be the core of Yee’s art.

Discontiguity is directly opposed to contiguity. And in regards to the degree

of ‘experimentation’ and ‘actualization of the experiment’ (in that the former

is a tendency to try something new, while the latter is the power to go beyond

that initial trial and turn it into a reality), the two have different

characteristics. So, if I were to say that the art of one person simultaneously

contained these conflicting or different properties, it might be a

contradiction in itself, or sound like a leap of logic. But one can find

similar internal factors also in the works by other ‘contemporary’ artists, and

not only in Yee’s art, who have built or are building their own independent

world of art. This is because, simply speaking, contemporary art has to engage

in an endless pursuit of novelty and also because newness is not accrued in a

single take but has to be accumulated continuously. The degree of

experimentation in contemporary art is registered not through a feast of empty

words, but only through the reification of novelty by readily perceivable

physical works.

In

that context, Yee has reified newness with every piece, and she continues to do

so to this day. How is this possible? What is the source of that power? I shall

say that it is Yee’s imagination, and through it, she was able to produce a

novel work each time. Strictly speaking, however, what I refer to here as

‘Yee’s imagination’ is the capability to change the order governing the

contents of established objects, stories, shapes, senses and cognition; to

partition new facets from within existing bodies already lumped into

conventional forms; and transfer the space and time that has been given into

another dimension of disparate images. That is how Walter Benjamin (1892–1940),

using the comparison of a folding fan, defined the faculty of imagination as

“the gift of interpolating into the infinitely small, of intervening, for every

intensity, an expensiveness to contain its new, compressed fullness.” In other

words, such an imagination recreates space as it folds itself shut and spreads

open again, and stages a situation by concealing or revealing an event, through

a mechanism similar to that of a fan.

Story

of MunKil (long Journey) (1999), one of Yee’s lesser known works

in the form of ‘text plus narration,’ clearly shows a version of that

imagination. This is the work I described in the introduction as ‘a hodgepodge

or re-creation of stories,’ and through it we can see Yee’s imagination burrow

into the inner details of the smallest of episodes from fairytales with which

we are all too familiar. And our observations do not end there, as we also get

to perceive—in the universality of the old fairytales that end with ‘happily

ever after’—Yee’s imagination as well as her ability to execute this by

extracting a thread from various topics including irony, violence, uncertainty

and pleasure, and weaving it into a new textual web like a spider. But this is

not her only web of tales. In Breeding Drawing (2005)

and the ongoing Daily Drawing (2005–), we get to

feel the multifarious but stubborn contiguity that results from Yee’s

imagination, and the parade of images performed by such imagination.

Breeding

Drawing is a series of twelve drawings of female figures on

traditional Korean paper with cinnabar: an ore used in Korean and other Asian

cultures that is ground into ink to draw paper talismans and Buddhist icons.

Here, twelve is not only the number of the separate pieces of art, but also the

result of the ‘breeding’ commanded by the title of the series. In brief, the

theme of this series is the mechanism of a certain drawing propagating itself.

In order to demonstrate the dynamics of that self-propagation, Yee flipped her

first drawing and retraced the image, creating the next drawing, then repeated

this process eleven more times; she then also made laterally symmetrical images

of every one of those twelve images. As a result, what started out as an image

of a girl performing a strange acrobatic feat as though she were in a Chinese

circus, propagates itself into an image of two figures with mirror-image faces,

and then into four figures in the next drawing, then six and so on until eventually,

the faces fill the screen, forming a symmetrical formation of the letter “V,”

thereby completing the Breeding Drawing.

Yee

received psychotherapy for an unstated reason around 2004. Through that

process, the artist became aware of ‘Mandala art therapy,’ for which she had to

fill one circle per day with drawings to alleviate her psychological problems.

She then applied that therapeutic method in her real life and work, which is

how her Daily Drawing began. There were only two

preconditions: that she complete ‘one drawing every day,’ and that the drawings

are in a ‘circle.’ These may seem rather trivial, but anyone who has actually

tried it will know how burdensome it is to meet such preconditions. And yet,

Yee has been meeting them without fail, drawing on a 30cm-by-30cm piece of

paper with colored pencils for about seven years now. Of the thousands of

drawings produced, she selected 176 of them, and introduced them for the first

time at her 2011 solo exhibition at Arko Art Center in Seoul, as part of an

‘installation art in the form of a drawing plus sound’ (the sound being Stabat

Mater, a Catholic hymn to the Virgin Mary). Visitors to the

exhibition experienced the artist’s wide-range of expressive abilities, as well

as an imagination of imagery whose elusiveness made it seem all the more

infinite. At the same time, through this coupling of a very simple and small

rule with the variables of human imagination and serial acts of creation,

viewers were also able to discover a vivid example of the construction of a dream

world that was unpredictable and irreducible like the emergences in nature.

Story

of MunKil (long Journey), created in 1999, rambles on—in the fashion

of Queen Scheherazade who spun an endless yarn of stories for One

Thousand and One Nights—about oft-heard but seldom read

stories. Breeding Drawing, created in 2005, propagates

itself symmetrically like plants in nature, and especially those that are

dicotyledonous. Daily Drawing explodes of

different images within identical circles like daily physiological phenomena

that follow a causal system of time in which each twenty-four-hour-day proceeds

from ‘breakfast, then lunch to dinner’ yet no two days are ever identical.

Through these works, we appreciate Yee’s art that is both discontiguous and

contiguous, as well as the sort of imagination that has built these dream

worlds of images. Actually, we will probably soon become overwhelmed by its

scope, strength, stubbornness and protean nature.

4. Painting For Out of Body Travel,

Structure of Yee’s Artistic Transition of Executing Subjectivity

In

the early years of her career in the 1990s, Yeesookyung mainly created artworks

from the perspective of cultural criticism. For instance, in the context of

criticizing the purity, originality, and self-referentiality of modern art, she

deliberately produced installation pieces that were effective applications of

postmodern methodologies such as kitsch, readymade, appropriation and pastiche.

Furthermore, she created works whose primary elements were appropriations or

alterations of mass media images and mass-produced goods, and unfolded an art

practice which critically analyzed female images that are produced and

stereotyped by mass media, sociopolitical systems based on her own specific

experiences and on sociological theories and cultural studies. Through such

projects, the artist was not only able to express the potential for

anti-aesthetic, non-artistic art to the Korean art world—which had started with

Art Informel in the 1950s and progressed onto abstract art in the 1960s and

1970s before moving on to Minjung art in the 1980s—but also embody feminist art

in a practical fashion amidst male-dominated mainstream Korean art.

However,

Yee did not stop at this type of art, which is productive in regards to

concepts and controversies, but which rarely draws a reciprocal response in

terms of aesthetic value or a viewer’s aesthetic experience. She neither

limited herself to contemporary art that was conceptual and critical in nature

nor produced self-replications of similar projects; rather, Yee executed her

art in new sensorial and perceptual perspectives which also satisfied

intellectuals.

I

believe that the uniqueness in producing such art is best represented in Painting

For Out of Body Travel (2000). The work displayed in her 2000

exhibition Song of the Land (2000) at Museum

Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany, combines the external forms of a ready-made

product with a one-of-a-kind creation. The art consisted of a kitsch landscape

painted by an anonymous artist and Yee’s intervention into the landscape, created

by halving the ready-made painting, extracting the painting’s colors, rendering

them into horizontal stripe patterns, and inserting them in between the split.

More intriguing than the physical form is the fact that the work claims to

serve as a ‘tool’ in an active manner by lending a favorable glance to the

viewer’s aesthetic experience toward art as well as by maximizing the illusory

aspect of such an experience. Yee’s Painting For Out of Body

Travel neither ridicules kitsch nor sneers at modern art.

Instead, it is an artwork in virtual reality that lures us to gladly surrender

our souls to the illusion of the painting, like in the Chinese tale about an

old man who, fascinated by the exquisite landscape painted on a porcelain vase,

walks into the painting. As the title hints, the work prompts the viewer to

travel out of the body. The artist herself wrote: “Relax and stare at the

center of the painting until you feel dizzy... you will finally experience

‘out-of-body travel,’ arriving at the landscape in the painting. When you

practice out-of-body travel, it is possible to fall into the waterfall or lake

in the painting.”

On

the other hand, Yee’s artistic transition has been manifested in her works

through the weaving of cultural differences. This is best represented by a

series of works, such as Parental Plates (2003)

and Translated Vase (2002/2006–). In 2003, during

her visit to Savona to participate in the Second Ceramics in

Contemporary Art (2003) held at the museum Palazzo Gavotti,

Savona, Italy, she went and interviewed twelve residents in Albisola and

Savona, which are sites that are well-known for the manufacture of porcelain.

The twelve interviewees personally selected a few porcelain plates inherited

from their parents or ancestors, and revealed to the artist the stories that

are woven into the plates. The artist captured the faces and voices of the

Italian residents with her video camera, who, though seated in a living space

of reality where they actually worked and lived, were traveling the micro-world

of reminiscence in the spatiotemporal setting of imagination activated by the

plates. Although perhaps considered mere objects, the plates functioned as a

time machine or Aladdin’s magic lamp at that specific moment. The video showed

the twelve people recall the lives of their parents’ generation in a sincere

and candid manner, before an artist from Korea, which is a country that is

unfamiliar to them. They shared with others their own experiences and memories

accumulated through such plain and ordinary objects. But video art, by its

nature, transforms such sharing beyond the one-to-one relationship with twelve

individuals, into something that can be disseminated and shared with any viewer

of the work Parental Plates. The artist would probably

have wished to produce this type of sharing (the pleasure of such sharing) not

only through videos, but also in forms with material and physical properties.

After the interviews, Yee had 20 near-replicas of the plates that had belonged

to the Italians manufactured at the Eran Design studio in Albisola, and served

Korean food on them to visitors at the opening of the exhibition. This would

probably remind one of Rirkrit Tiravanija (1961–) and his art performance of

serving his own cooking to the visitors to the gallery. It is this very art

that Nicolas Bourriaud (1965–) imputed meaning to, stressing “a place where

people once again learn what conviviality and sharing mean” and “exploring the

possibility for relational aesthetics.”

Taking

the circumstances into consideration, Yee might be included in such an

aesthetic category. However, Yee’s art goes beyond offering a space of general

cultural sharing and appreciation, to offering a ‘subjective experience’ in

which individuals bring out their indivisible inner selves in a stranger, who

gladly shares them with a large number of other individuals. Such structure is

‘the dividing∙sharing of individuality’ and ‘rendition of varied emotions’ that

can only exist in the cultural form of art.

5. Translated Vase, The Task of the

Translator

The

art project, Parental Plates, has a prior

history: Translated Vase Albisola (2001). In 2001,

Yeesookyung devised a translation project to be submitted for the Ceramic

Biennale in Albisola (2001), Italy, in which an Italian potter named Anna Maria

‘translated’ 18th-century Joseon porcelains. What translation refers to here does

not correspond to the manner in which a contemporary potter molds works into

Joseon porcelains in physical or visible dimensions. If it does, it would be

considered ‘reproduction,’ rather than ‘translation.’ The artist recited a

Korean poem translated into Italian to Maria, with a motif that centers around

white porcelain, namely Ode to a Porcelain—a 1947 verse

by Kim Sang-ok (1920–2004); she then requested that the potter expresses

imagery that comes to her mind into ceramic works. What Yee attempted to

‘translate’ was an interpretation between different languages across cultures

as well as between imaginative and physical features. At first glance, the

results of the translation resembled ordinary porcelains in Asia in external

appearance; a closer examination, however, reveals that they are twelve foreign

ceramic vases, produced from different ceramic cultures of the East and West

and which do not fall under any conventional category of ceramics. These twelve

vases allow viewers to cross the familiar boundaries of cultures to which they

belong and have gotten accustomed. The vases also trigger peculiar sentiments

and imagery, not fixed to any specific race, territory, history or taste.

However, what we need to keep in mind is that such uniqueness does not stem

from something rootless that floats aimlessly. Given that such peculiarity is a

manifestation occurring in the negotiating process of Joseon porcelain and

Italian ceramics, the vases are truly art of today, developed with nourishment

drawn from fairly deep roots. Simultaneously, they are contemporary works of

art in the here and now, created in an experimental manner through cultural

rendition and cooperation. In short, Translated Vase Albisola is

a contemporary work based on ethnic and cultural backgrounds uniquely formed by

Korea’s Joseon dynasty and Italy as well as by the past and present.

Furthermore, Parental Plates, which Yee created two

years later from the aforementioned work, is another contemporary work featured

in the present context, breaking free from grand narratives and using sources

of individual family histories and memories.

According

to Benjamin, “The task of the translator consists in finding that intended

effect upon the language into which he is translating which produces in it the

echo of the original.” In other words, the translator’s task is to translate

the history of the original in the context of the present time as well as to

realize the potential of the original in the here and now. I believe that Yee’s

pieces constitute an art practice which parallels such a task. Art is not a

denial of origins/sources under the banner of cultural plurality and nomadism

of artistic tastes; rather, it is the manifestation of essential factors

resonating in our lives here and now, and a site for possibility of narratives

of histories, communities and individuals.

In

the same context, Yee’s 2011 work titled Dazzling Kyobangchoom (2011)

presents significance. The work realizes unique aspects of Korean modern

history and culture in the form of a symphonious combination of ‘sculpture,

site-specific installation art and performance (dance and music).’ The main

themes of Dazzling Kyobangchoom are the

preservation of ‘Kyobangchoom,’ originally a dance from Joseon Dynasty

generally performed by state-sponsored female entertainers, as well as the

rebirth of this dance tradition into a novel artistic form in the present.

First of all, the artist took note of the historic fact that the traditional

dance degenerated into a form of sexual entertainment during the era of

Japanese colonial rule. She organized five Kyobangchoom performances on a stage

of her own design that utilized, both directly and indirectly, conditions

specific to ‘Cultural Station 284,’ the former site of the central Seoul Train

Station that was recently restored in order to serve as a complex cultural

space in 2011 after three years of renovation. What is notable here is the

mechanism in which the social and historical consciousness of the artist is

actualized into art, as well as the aesthetic approach employed for the

exploration of not the abstract space for art, but rather, the overall context

of an actual specific site. Of significance is also the open attitude that

studies media and expressive methodologies on multiple levels from a

pluralistic perspective. In so doing, the artist brings together her art in the

context of the contemporary. On the other hand, Yee has established her own

uniqueness in her practice and identity as an artist by establishing concrete

instances from modern and contemporary Korean history and contemporary culture

and art as the fundamental narratives and original concepts for her art.

6. The Very Best Statue: Universality and

Uniqueness of Beauty

During

Goryeo and Joseon Dynasties when Korea’s ceramic culture was at its most

refined stage, ceramic masters did not hesitate to destroy their creations when

they were unable to meet the standard of ‘highest quality’ and were considered

failures. While they appeared similar and adequate enough in others’ eyes, they

were considered by ceramic artists as defective products that should not be

shown to the world. The fact that this tradition has continued to the present

suggests that there are strict aesthetic criteria among master potters beyond clear

logical description.

Interesting

enough, Yeesookyung has continued a series of works titled Translated

Vase, which uses gilt to paste together discarded shards and pieces

of pottery broken by ceramic masters into a new sculpture with a new life. The

series would either probably fall under the form of development in Translated

Vase Albisola, as described above, or under an entirely different

series; but the artist connotes contiguity between them through the

title, Translated Vase. If so, then, what does ‘translation’

mean in the latter series? To simply put, it is a translation between

‘fragments’ and ‘the whole’ or ‘the discarded’ and ‘artworks.’ However, I

suppose that Translated Vase stands at a point

beyond such an interpretative perspective. The point is a final destination for

all artists; in other words, it is the point of dynamics created between ‘the

realization of absolute beauty’ and ‘the practice of every single minute to

achieve it.’ The reason ceramic masters inevitably destroy their works for

failing to meet standards is that their minds and senses have an absolute

standard for beauty. To reach that standard, they willingly endure the pain and

anguish that come from breaking ceramics into shards. However, it is of great

significance that Yee uses abandoned shards to pursue absolute beauty according

to the definition of contemporary art. This signifies a reversal of dynamics.

Although it may obviously be difficult to attribute this only to the reversal

of dynamics, it explains Translated Vase effusing

a distinct exquisiteness from what is generally assumed to be beautiful. On the

other hand, the fragments of ceramics appear as if they were body organs that

have erupted from beneath the smooth skin, becoming disfigured, and going

through the process of deconstruction/reconstruction in an odd manner. And yet,

they are perceived as attractive objects for their cold yet soft textures as

well as for the glamorous yet decorous shapes of gilt layers weaving broken

shards. It is the combination of these contrasting aesthetic properties that

intensifies the unique artist aura of Translated Vase and

provides the viewers with a moment of unique unparalleled exquisiteness.

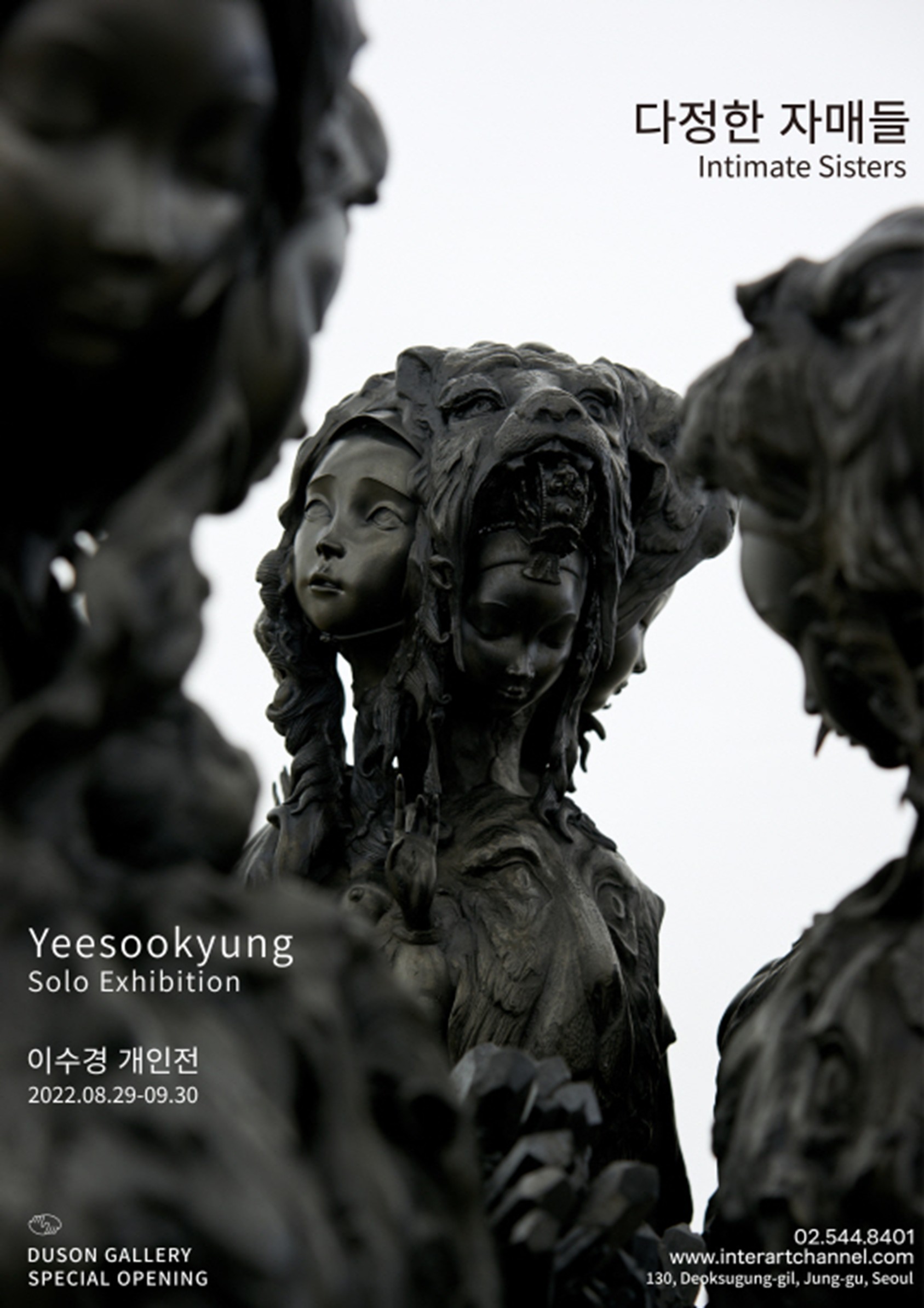

A

similar sense of aesthetic dynamics is also demonstrated in The

Very Best Statue (2006–), a project shown in Echigo-Tsumari Art

Triennial (2006), the Anyang Public Art Project (2007), the Liverpool Biennale

(2008) and the Kyiv International Biennale (2012). As briefly mentioned in the

introduction, this project consisted of the artist asking people to state their

favorite body parts from images of gods or saints and assembling them to create

the ‘best sculpture.’ Through this process Yee created a standing statue of

what appeared to be Jesus wearing the crown of thorns, yet with Asian eyes,

along with Confucius’ right upper torso and a left half that belongs to Buddha.

Another statue of a near-naked Jesus coming into the world with a soft smile across

his face, reminiscent of the face of Virgin Mary, recalled the image of

Crucifixion with his both arms stretched out. What is surprising is that if one

were to ponder and verbally explain the idea, those statues would seem to turn

out grotesque or even monstrous; however, if you actually look at them, one

does not find them unnatural or strange. The icons are in harmony, friendly yet

sacred to the extent that viewers seldom find them odd, distorted or degraded.

This is possible because the individual features claiming to be the best by

their own standards were recreated into that a whole consisting of disparities

by the artist. This is similar to the dynamics through which Translated

Vase becomes an uncanny, incarnate beauty composed of pottery

shards discarded by ceramic masters who adhere to strict standards of beauty.

In The Very Best Statue, individual parts selected as

‘the best’ based on the aesthetic concepts as well as religious mental

representations prevalent in the general public in each culture are re-created

as an icon that is simultaneously universal and unique, and familiar and unfamiliar.

As

I appreciated Translated Vase and The

Very Best Statue, I came to think of the relationship between

universality and individuality. We generally assume that there is an absolute

and fundamental beauty. In addition, we usually say that beauty endures beyond

space and time and that universality is achieved through its dissemination

among people. Beauty is purely unified and whole. However, Yee’s works show

that it is possible for absolute beauty, which is both unified and whole, to

not only consist of a combination of individuals, but also of a network

comprising heterogeneities. Her art presents the possibility that an innovative

type of universality might be achieved through the translation of things that

are distant from one another and whose origins are extraneous.

Slavoj

Žižek declared that in the schematized time of past, present and future,

nothing really new can emerge. For the truly new to emerge out of the

destruction of pre-existing circumstances of time systems, relationships and

networks, which cannot be accounted for by reference to existing causal

relationships, Žižek wrote, the ‘sublime’ marks the moment in which something

emerges out of nothing. “When, ‘against their better judgment,’ people

disregard the balance sheet of profits and losses and ‘risk freedom’... The

feeling of the Sublime is aroused by an Event that momentarily suspends the

network of symbolic causality.” The important phrase here is to ‘suspend the

network of symbolic causality and risk freedom.’ It probably sounds reasonable,

but specifically, how is it possible? From the aesthetic perspective, this

would mean to disconnect the network that exists among nature, forms, modes and

conditions for beauty that is premised in the name of universality, and then

venture into individual freedom of creativity. Remember that I have emphasized

the experimental spirit discovered in Yee’s art several times by broadly

examining her art in various dimensions that encompass the appearance and

nature of her works, the mechanisms and consequences, and in light of

presentation and appreciation. I also hope that readers will not forget my

assertion that, while Yee’s pursuit of ‘experimentation’ has moved in

directions not in line with conventional trends in art, this does not simply

mean the denial of existing trends, but rather, that this pursuit is linked

with a practical desire to derive the production of certain things. Her pursuit

of art will truly become a case of contemporary art in which, as Žižek stated,

the suspension of the network of symbolic causality and the risking for freedom

will enable ‘something really new to emerge.’

Lastly,

I must make the following confession as an art critic. I can tell you what is

happening in the arena of contemporary art, but I cannot specify its exact

scope. In addition, when an artist introduces an experimental work of

contemporary art, I am capable of adding a critical dimension to the work by

interpreting and analyzing it. However, I cannot make any assertion regarding

where the artist will be heading next, what kind of works she should produce,

or even what kind of aesthetic value she may pursue. This is partly due to my

own incompetency, but more importantly, it is due to the fact that contemporary

art itself has been progressing based on an extremely individual aesthetic. Of

course, that individual aesthetic is able to be assigned a name only after it

achieves artistic success, and the individual aesthetic discussed through this

lengthy essay is the particular aesthetics of the artist Yeesookyung.

1

Žižek, Slavoj, The Ticklish Subject: the Absent Centre of Political Ontology, (

London: Verso, 1999), p. 43

2

For the subsequent headings, I have stated a title of a work by Yeesookyung,

followed by the core concept or argument of my criticism of it.

3

“Art is a game between all people of all periods”

: Bourriaud, Nicolas, Esthétique relationnelle, Simon Pleasance & Fronza (trans.),

Relational Aesthetics, (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), p. 19

4

Benjamin, Walter, “Einbahnstraße”, Gesammelte Schriften Bd. IV/1, Unter

Mitwirkung von Theodor W. Adorno und Gershom Scholem hrsg. von Rolf Tiedemann

und Hermann Schweppenhäuser, (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1981), p. 117

5

Yeesookyung’s Homgpage www.yeesookyung.com

6

Bourriaud, Nicolas, Esthétique relationnelle, Simon Pleasance & Fronza

(trans.), Relational Aesthetics, (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), p. 70

7

The full text of the verse is as follows: In the freezing blizzard, the pine

tree stands faithfully green, / Its crooked branches sway in the wind. / A pair

of white cranes flies over and sits, and folds their wings. // The day the

tingling of a wind-bell resounded from lofty eaves. / When my beloved, whom I

have waited and longed for, arrives, / I shall bring out the liquor I’ve kept

under flowers. // The elixir of life sprouts from a slanted rock chasm. /

Auspicious clouds float, a stream runs, / A deer still frisks about the woods.

// Skin as white as ice even after burning in fire / Even a speck of dusk can

leave a flaw. / The day, lost in clay. How simple and honest.

8

Benjamin, Walter, “Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers”, Gesammelte Schriften Bd. IV/1,

p. 16

9

Žižek, Slavoj. Ibid., p. 43