Western

audiences’ particular enthusiasm for Lee’s Animatus stems

from the way his work bestows solid reality upon their fading fantasies. Every

desire supplements reality. Just as Pygmalion lamented the women of Cyprus who

had fallen into prostitution and sought to create for himself a pure and

beautiful woman, Americans may likewise have embraced Disney’s innocent, lively

characters to compensate for a dark reality corrupted by capital.

Lee, like Pygmalion adding flesh and bone to his fantasy, gives human skulls

and ribcages to Disney’s flat, cartoonish bodies, turning them into living

beings. Through Lee’s Lepus Animatus (2006), Bugs

Bunny becomes a friend with an internal structure and real bones. The

ridiculous, implausible movements of Goofy in Ridicularis (2008)

become rational and convincing through their skeletal logic.

For

audiences who have already grown too old for cartoons, these fantasies do not

simply repeat the original format but appear instead as archaeological

specimens—like fossils of extinct dinosaurs—providing an indexical assurance of

absence. By demonstrating Disney’s dream of making the non-human human—an

impossible yet beautiful Pygmalionic fantasy—Lee solidifies his stature as a

sculptor and grants archaeological concreteness to a fading chapter of American

popular culture.

Of

course, this is not reality but fantasy. Yet the peculiar feature of this

fantasy is that these animals deviate from their natural comportment and

acquire human attributes, existing as though they were human. In other words,

we do not marvel at a mouse (Mickey Mouse) but at a mouse that has become

human, a mouse with human bones, the trace of a subject (the human) emerging

within the body of the Other (the animal).

To understand the essence of this fascination, imagine the reverse: a human who

has become a mouse, or a human body inhabited by a mind convinced it is a mouse

and behaving as such. From a Freudian perspective, such a person would be a

mentally disturbed individual requiring treatment—like the unhappy “Rat Man,”

unable to settle within the “order of the father” and trapped in unstable

traumatic images.⁴

Perhaps

the true value of Animatus can be understood in

relation to the difference between the human-mouse and the mouse-human—that is,

the pleasure of seeing the familiar, normal subject situated within the strange

body of the Other, and the discomfort of seeing the Other’s grotesque, abnormal

body enact the familiar behaviors of the subject.

Animatus thus inhabits the space between these two

affects. It relates to the uncanny overlap Freud called the “uncanny”—the

simultaneous experience of familiarity and strangeness: the childlike wish that

a cute Mickey Mouse doll might one day speak to us, and the unsettling,

chilling feeling if that wish were ever realized.⁵

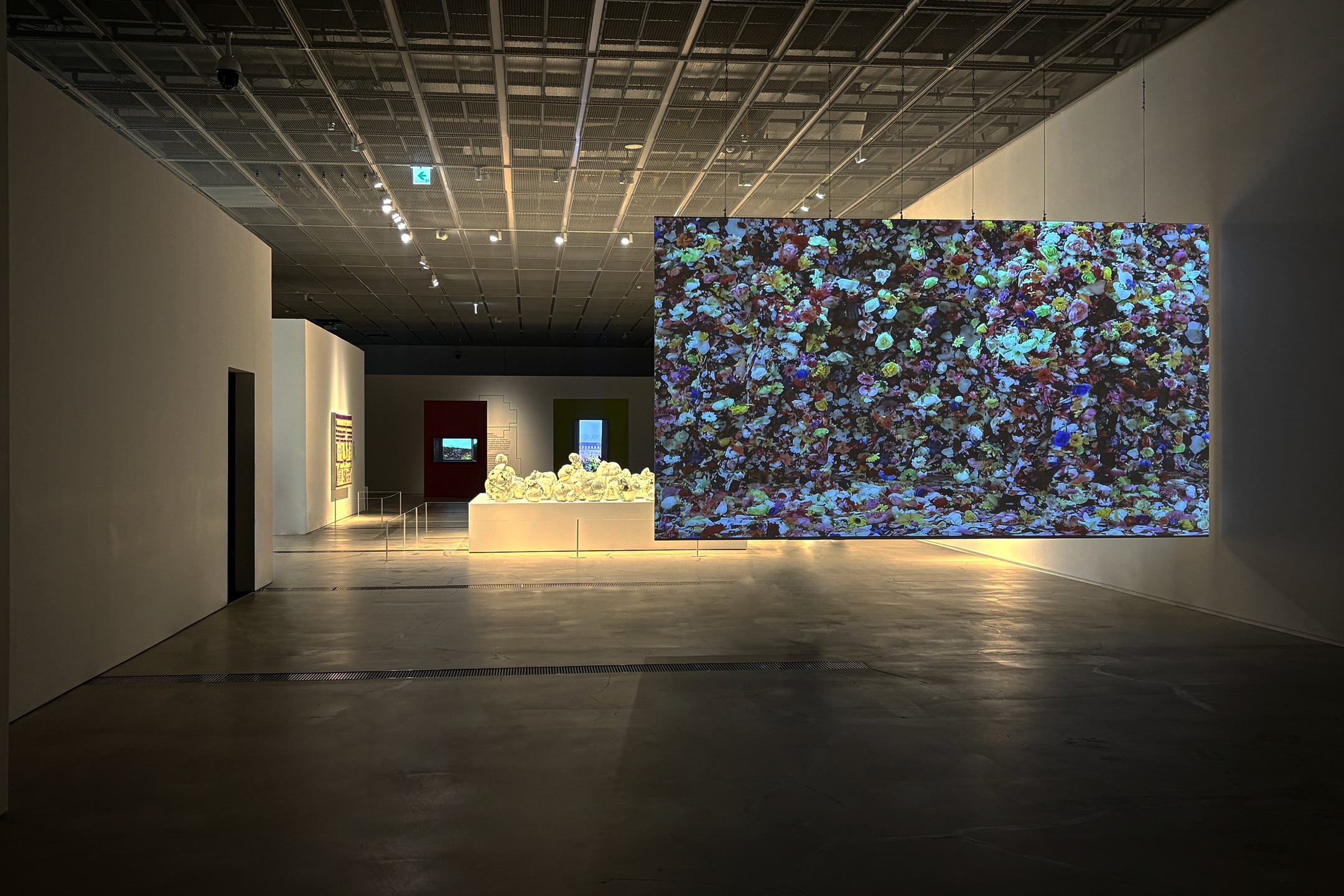

Accounts

of visitors feeling a strange sense of unfamiliar overlap after seeing Lee’s

works displayed in a Swiss natural history museum—like newly unearthed fossils

of primitive animals—illustrate precisely this uncanny experience. Beneath the

delightful imagination and skilled sculptural finish of Animatus lies

a subtle code concerning the contradictory desires of the subject revealed

through the body of the Other.

The

Pygmalion myth leaves two contradictory effects: one is the positive belief

that earnest desire will be fulfilled, and the other is the perverse, negative

belief in indulging fantasies detached from reality. How does Animatus appear

to us? For some, it affirms the human charm of these characters; for others, it

may seem like the impure invasion of humanity that corrupts the characters’

animal innocence.

Regardless of interpretation, the faint overlap between subject and Other

that Animatus produces summarizes the yearning

that lies between sculpture and reality, human and non-human, lack and

supplement within Lee’s practice. Sculptures that want to be human yet can

never be human; the Pygmalionic desire fulfilled “only by traversing the

fantasy”; Animatus by Hyungkoo Lee leaves an

unfamiliar index of sculpture’s contradictory longing by desiring what can

never be desired.⁶

¹

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Pygmalion, London: printed for J. Kearby, No. 2,

Stafford-Street, Old Bond-Street; Fielding and Walker, Paternoster-Row; and

Richardson and Urquhart, Royal Exchange, 1779, pp. 31–33.

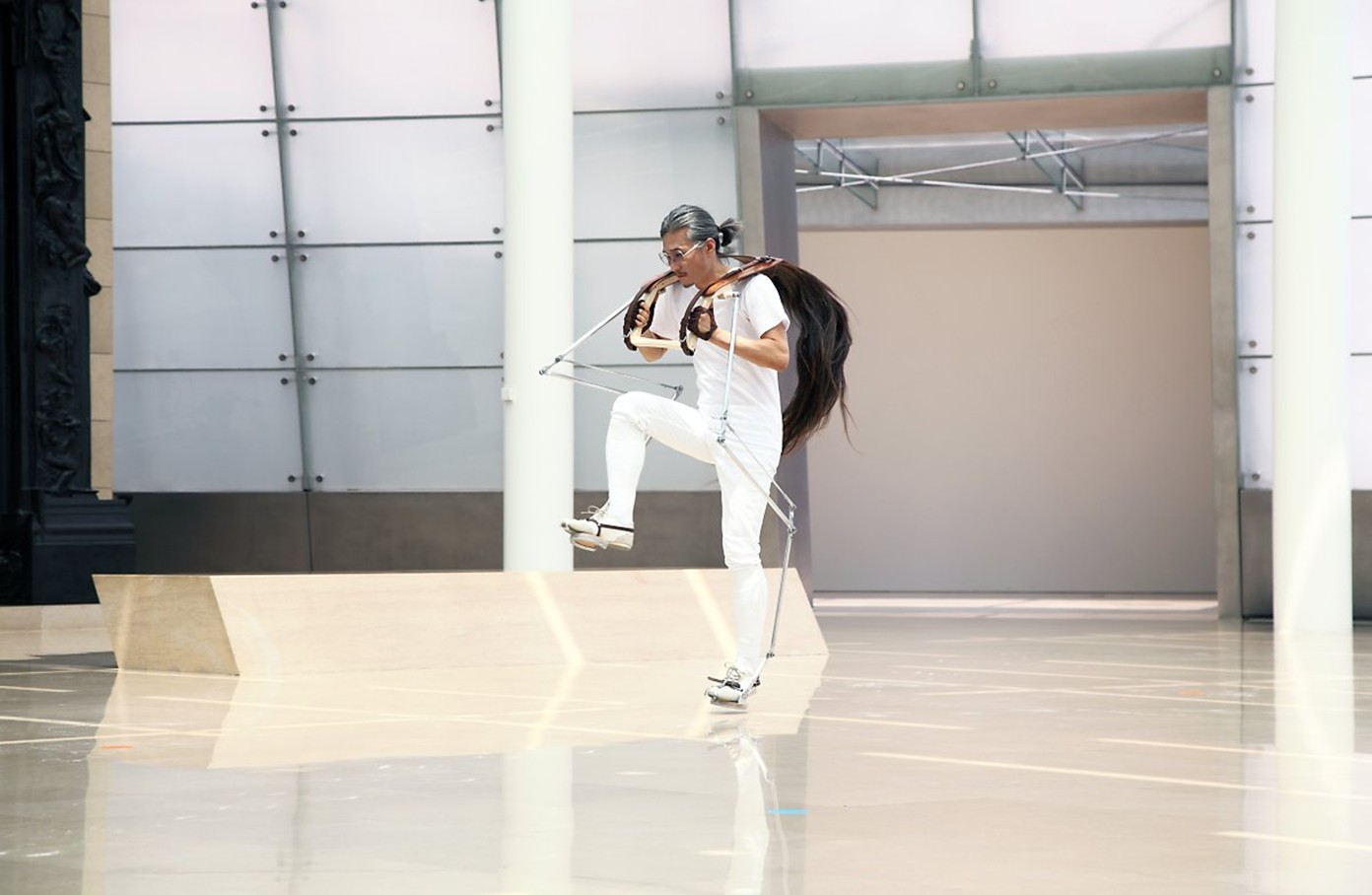

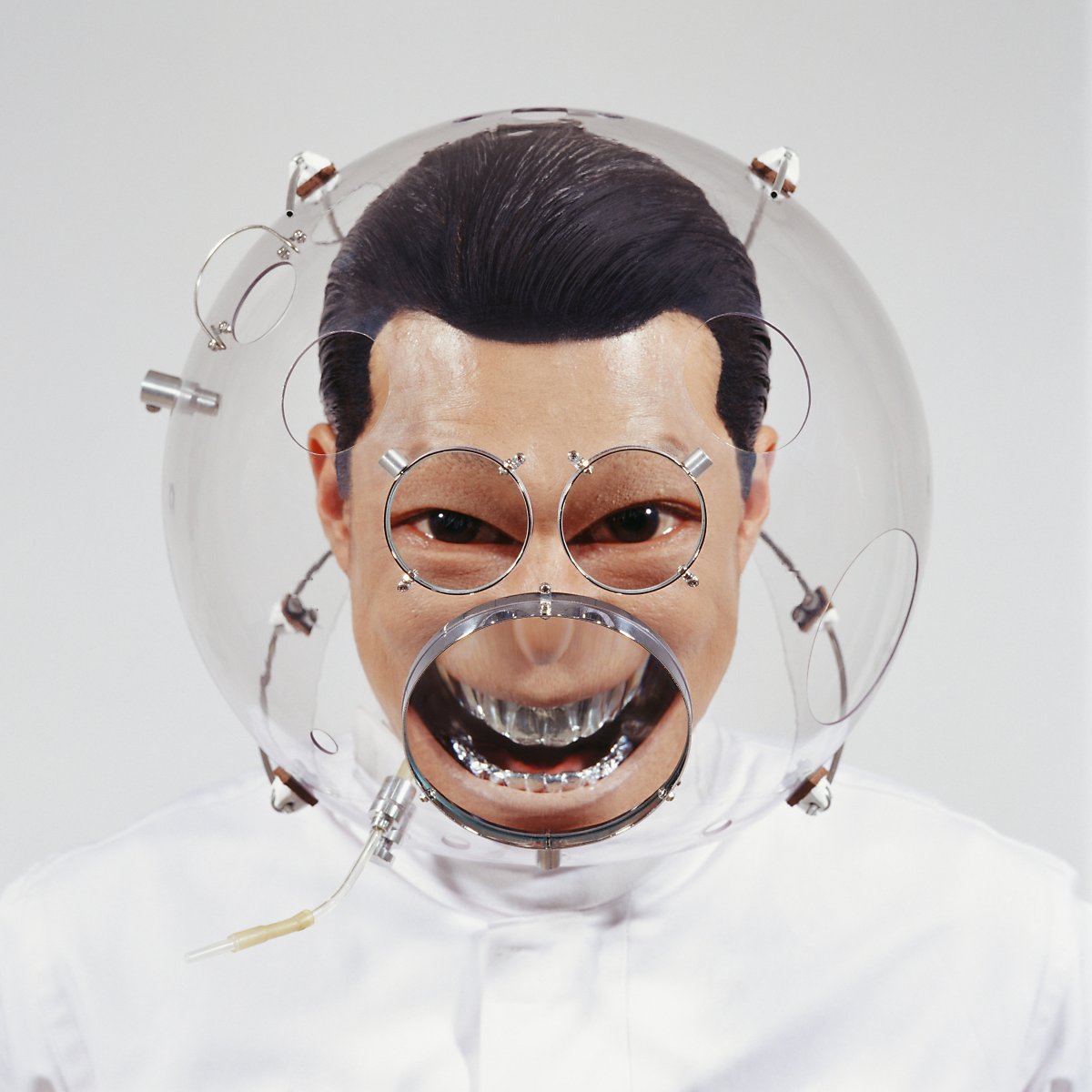

² This perspective is even more clearly expressed in the prosthetics from Lee’s

early The Objectuals Series. For further

discussion, see: Jongchul Choi, “What Does Sculpture Want? The Posthuman Myth

in Hyungkoo Lee’s Sculpture,” in 《Korean Contemporary Artist Highlights IV – Hyungkoo Lee》, Busan Museum of Art, 2022.

³ Refer to Jacques Lacan, “In You More Than You,” in The Four Fundamental

Concepts of Psychoanalysis – The Seminar of Jacques Lacan Book XI, ed.

Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan, New York: Norton, 1998, pp.

273–274.

⁴ Sigmund Freud, “The Rat Man,” in The Freud Complete Works 11, trans. Kim

Myunghee, Seoul: Open Books, 1996.

⁵

Sigmund Freud, “The

Uncanny,” in The Freud Complete Works 14, trans. Kim Myunghee, Seoul: Open

Books, 1996.

⁶

This essay is an adapted version of a text originally published in the

catalogue of Hyungkoo Lee’s

solo exhibition at the Busan Museum of Art (March 29 – August 7, 2022).