Accumulated

over some time, Hyungkoo Lee’s works show great diversity. I look through

photographs and lists of a hundred or more works uploaded on his website. I

like his sleek and refined works. The beauty of the proportionately flowing

curves and the flawless finish brings me satisfaction. Perhaps this is because

they are not abstract substance but copies of nature, carved out by the

weathering of time? There is nothing unnatural about it. The contentment comes

not from a simple studium; I anticipate the beyond where the punctum lies.

I

wait until that expectation is met in reality. I did not simply fall for the

positivity coming from the smooth cover. It was not about a fascination for a

beauty that removed itself from dirty, troubled and hideous things. I touch and

smell the sleek surface of the work again and again. There is a power in the

work that brings me to appreciate it with time instead of stopping short at

enjoying the instinctive beauty. What lies beneath this smoothness? What kinds

of stories are hiding down there? What about the smell? I picture in my head

the memories gradually maturing beyond history and structure.

There

are other directions that could be taken in classifying the works of Hyungkoo

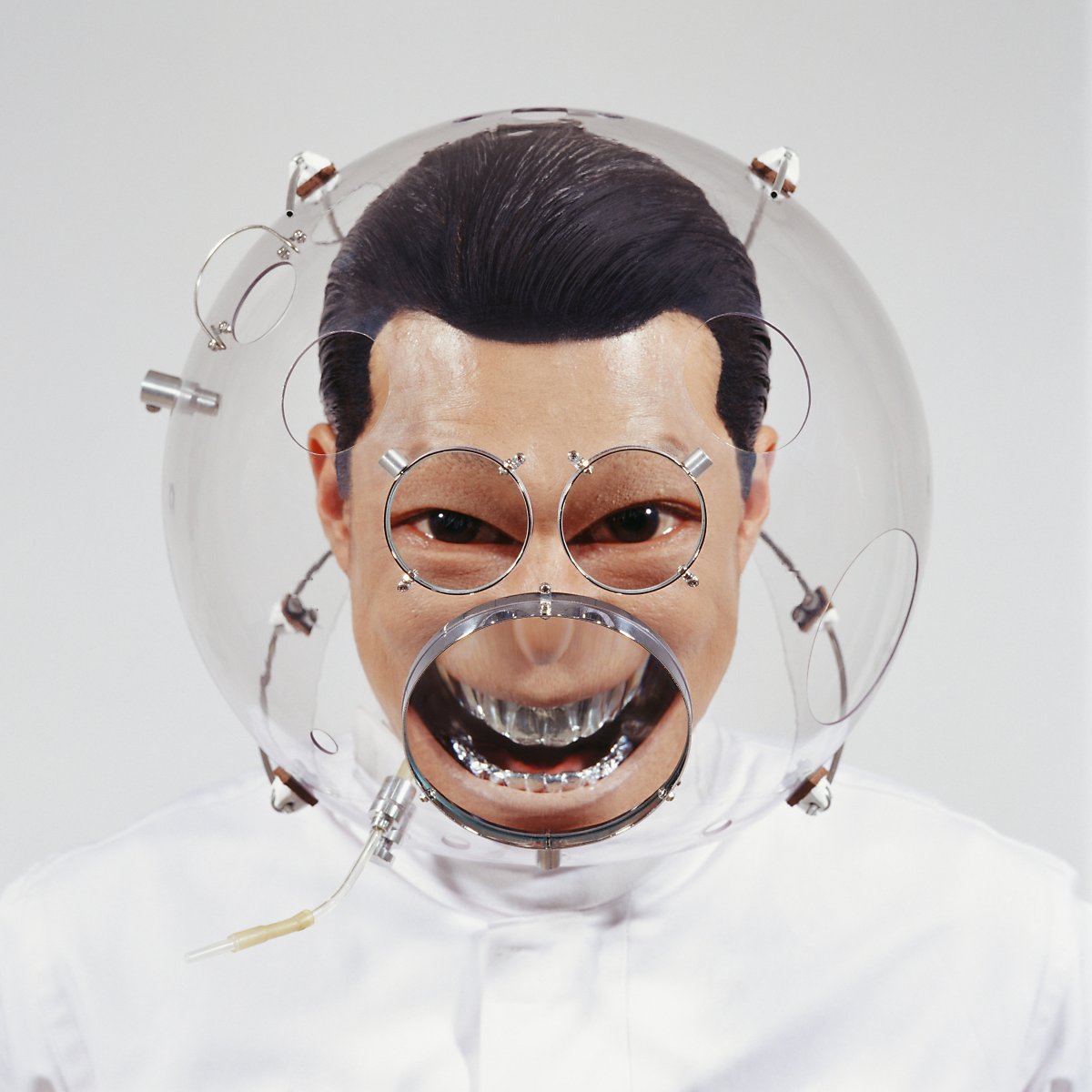

Lee, but his representative works include ‘ANIMATUS’, a series of works based

on his studies of anatomy, and the ‘Helmet’ series, which highlights a certain

part of the body. The following are the works that seem to serve as pivotal

turning points in terms of content and direction as I see it.

Helmet

3, 2000 ANIMATUS,

2005-2006 Fish Eye Gear,

2010 Instrument 01,

2014 Kiamkoysek, 2018

In

the chronology of the artist’s works, ‘Helmet’ comes before ‘ANIMATUS’.

However, if an anthropologist from the distant future with no prior knowledge

were to logically reconstruct his works, s/he might decide that ‘ANIMATUS’

precedes ‘Helmet’. S/he might say that ‘ANIMATUS’, a reconstruction of cartoon

characters’ bone structures based on the artist’s research on anatomy, bears

content serving as a root that helps articulate the works of ‘Helmet’, which

exaggerate the body. However, upon discovering the artist’s notes, which point

to the drive for the ‘Helmet’ series—the urge to overcome one’s physical

inferiority in size within a society as a foreigner—the anthropologist from the

future might correct the initial analysis: cyborgian imaginations first,

followed by the encounter with anatomy in the course of research led by the

imagination.

Studies and works that focus on the movements of fish or horses

that did not make it to the classification above are still closely related to

anatomy as well as the principles of kinetics. They are demonstrations of his

interest in the mechanisms of life and organisms, and the sensation and

response to the exterior. Whether the artist is conscious of it or not, it may

not be so far-flung to assume that the entirety of Hyungkoo Lee’s works are the

outcome of exploration and imagination on the topic of cyborgs.

Cyborg.

The word cyborg first came to be used in the 1960s. It is a compound of the

words ‘cybernetics’ and ‘organism’. As organisms are homeostatic and exercise

control, these two words do not automatically produce a new meaning. However,

this word was invented by Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline in an article titled

“Cyborgs and Space” to demonstrate their design, where a single organism is

attached to an artifact as an extension of itself and the artifact is connected

to the controlling function of the entire organism. On top of the simple

significations of each word, the term cyborg embodies the implication that

artifacts are attached. The title of the journal that published this paper was Astronautics.

As space is not where humans live originally, humans cannot survive in space

without supplementation.

It is clear that this word was devised from an

imagination of an organism with attachments necessary to survive in space as a

part of its own body However, the same kind of imagination is centuries old.

The first thing that comes to mind is Icarus from Greek mythology. He wore the

wings his father made for him and soared to the sky to escape the maze. It is

one among the essential natures of humans to make extensions of the body out of

necessity, or in order to realize a new potential. How many Icarians have

risked danger and stepped off the ground? To be precise, a cyborg should be a

single organic control agent even without deliberate will, as the attached

exterior supplementation is completely a part of the organism. However, a

cyborgian imagination is closer to the essence of humans’ existence, who have

drawn resources from the exterior for survival as a critical part of the

prosperity of the species.

Whether

the cause was an asteroid collision or something else, the dinosaurs went

extinct. After the dinosaurs’ extinction, the battle of the remote ancestors of

the human race to pass down life must have been a desperate one. Humans cannot

fly and are barely capable of swimming. Our speed ranks lowest among other

species of the same size, and we are without notable strength, protective

thorns or any other distinctive talent whatsoever. It is difficult to imagine

success in the competition to win over food with some natural gift. If the

ancestors were simply idling about, they must have all died out by now, except

for those who practiced a cyborgian imagination with tools at their hands.

Humans are descendants of beings who had no choice but to make something from

the extensions of the body and mind. The future of those humans who have

enjoyed prosperity dependent on tools should continue on with the imagination

of their ancestors in order to survive.

Fundamental

introspections such as imagination or essence aside, the cyborgs entering the

picture embody radically political implications. Most of the revolutionary

points that Donna Haraway elucidated in “A Cyborg Manifesto” 30 years ago still

hold to this day. The most frequently addressed form of cyborgs came from

medical causes or demands. With the practice of adding prosthetic hands and

legs to replace the limbs of those with disabled arms and legs, then connecting

nerves to motors to have control over them with thoughts, cyborgs in the true

sense are emerging. ‘The Six Million Dollar Man’ who used to be on television

is now among us. Surely, there is an increased chance that not only sensory

organs such as eyes or ears, but also internal organs could be replaced. The

advent of such cyborgs in the field of medicine brings about incredible changes

in terms of people’s quality of life and longevity.

A

truly revolutionary chapter will begin with a cyborg, if it comes, incorporated

with technology that could do away with the differences in the given physical

condition by reinforcing elements such as physical capability or appearance.

While Hyungkoo Lee expressed the feeling of being smaller or weaker among

westerners by means of exaggerations through lenses or optical curves and

artistic expression, technology has reached a stage where such imaginations

could be realized. As Haraway noted, if reproductive functions and sexual

differences could be erased upon demand, there would be no need to continue

with the dominant social structures. This is not only a problem engendered in

terms of gender politics, but a revolution in every corner of society. If we have

control over our capabilities according to our decisions, a change is in demand

in our current society, which bases itself on ‘excellence.’

The

question of what will take the place of the existing order after its collapse

remains to be answered. Ultimately, becoming a cyborg should not end up

reinforcing the conventional order due to cost, or result in a devastating war

from escalated conflict between cyborgs augmented only in physical abilities,

as in certain futuristic imaginations. Perhaps instead, a salvation to surpass

the dismal future pictured by technological predictions and imaginations would

come from artistic imagination.

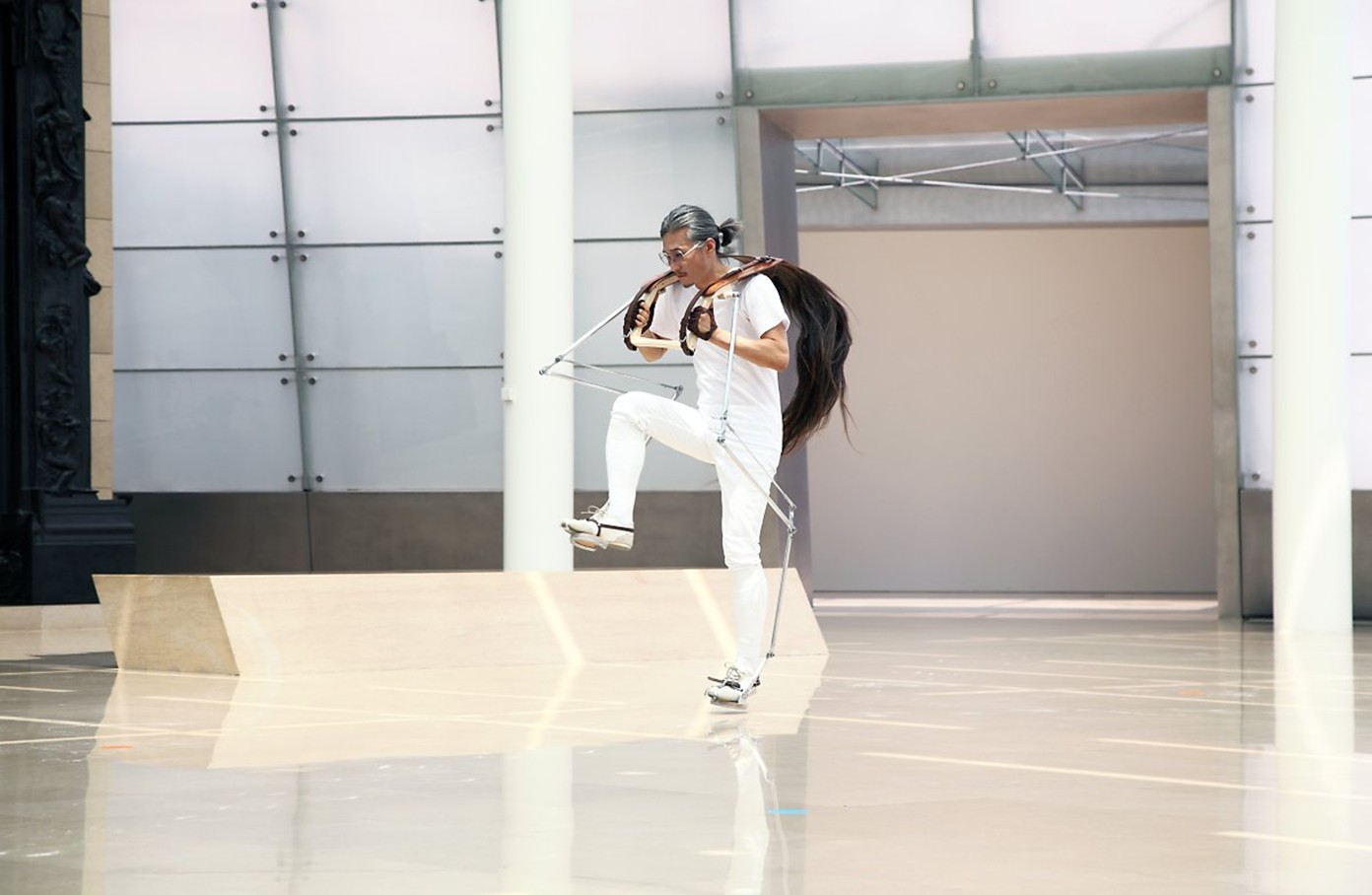

Kiamkoysek,

a new work presented this year, suggests that Lee’s artistic direction did not

take the path of logically investing in the initial issues of his earlier

works. Attempting to represent and experience the fish and horse’s way of

seeing is more about offering a new experience, although the work does extend

from his research on the physiological and physical structures of organisms.

The artist himself carried out a performance with the tools made to venture

into the limited experience made possible by restricted vision.

What kind of an

experience could such a performance have been for the artist? He must have felt

something new from the experience, enabled by the limited sensations, as

implied by pictures from the perspective of an insect that sees only in black

and white. Also, he is well aware of the fact that the restriction in sensation

is directly related to the anatomical structure and the movement of the

organism. It was quite impressive to see the way he moved in demonstrating

while explaining how the position of the eyes of the fish, which can see only

to the left and right sides of its body, must have made it swim by waving side

to side.

A

new experience made possible by limitations in sensation. The title of this

work derives from a Korean word that refers to oddly formed stones, whose

pronunciation is romanized as ‘kiamkoysek.’ This mark is again read

phonetically and transcribed in Korean to become the Korean title of the work.

The title and the process of its formation clearly show us what he is trying to

offer to the audience—the unfamiliarity and new feelings engendered from the

differences originating in translation and retranslation; a strategy and

approach that led to a word meaning ‘bizarre stones’ or ‘landscape with a great

scenery’ to be realized as ‘kiamkoysek,’ which is without a clear definition.

This is what serves as the material and structure for the exhibition.

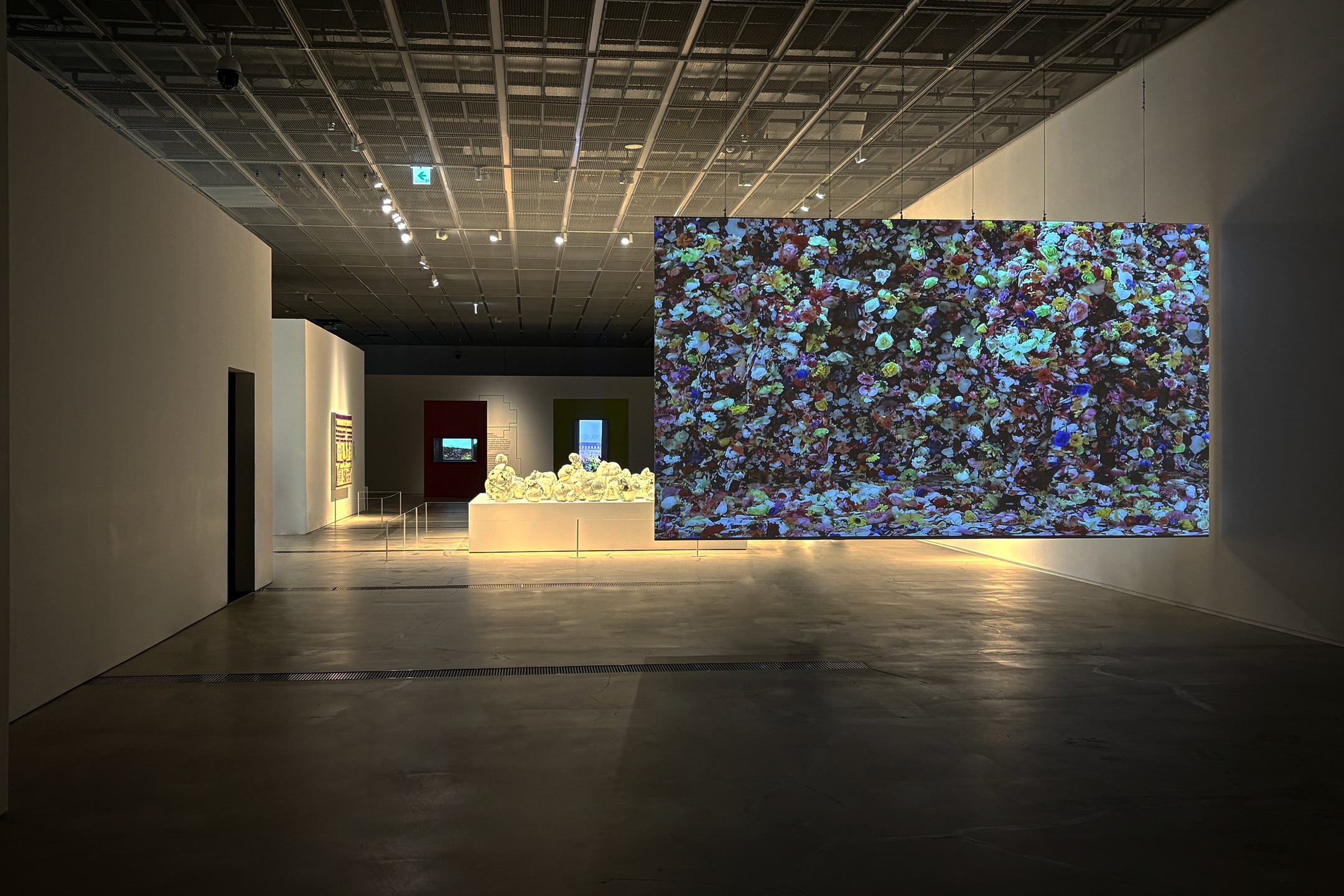

The human

bones are separated into each of the following components and enlarged 10 times

in the exhibition: left femur, left patella, left tibia, left fibula, right

clavicle, right scapula, right humerus, left humerus, left ulna, left radius,

right coxal, right femur. According to the artist, he has magnified them

without any alterations. Yet the ‘magnification’ itself is enough to allow a

distortion of the sensation and present a whole new experience to the audience.

An experience of encountering a shrunken self in cutting across a gallery space

that is at once a grave for a dinosaur but also that of a human. This would be

a journey of taking steps into one’s own inner world as well as confronting a

space that restlessly expands itself.

Rather

belatedly exploring the works of Hyungkoo Lee, an artist who could be counted

as one of Korea’s representative sculptors, I was fascinated by their

appearance and thrilled by the questions they raised. I hoped that the

questions he brought up from the early stages of his works would overcome the

immaturity or bluffing of a young man and reach an imagination of salvation. It

is easy to get angry at racists, but it is difficult to make that into art.

Hyungkoo Lee’s process of exaggerating the body to overcome a drawback in size

was not merely an artistic joke, but an active and direct counterattack. His

works were beautiful, and clear in their message. As if accumulating stories of

fiction, the structures made out of knowledge and facts from physics and

biology, as well as imagination to fill in the gaps, must have deeply impressed

a large number of audiences.

I

do appreciate his works to this day, which maximize the aesthetic effects by

representing the fish’s eye or the horse’s movements with devices or simple

extension and contraction while investing heavily in the problem of sensation;

they provoke sensations in the audience and offer new experiences. Yet much to

my regret, I do not think that he pushed far enough with the works, which

started out with the task of discovering ‘difference’ and surpassing it, to

address the question of salvation. While on this detour, he is making aesthetic

attempts at sensation and space. It is clear that the resulting works would

receive positive responses and reviews through their aesthetic achievement. A

line of reviews on his works still hovers about the same points, because even

those works of the aesthetic world which skipped over the salvation are, in

reality, yet to be complete. It is difficult, and not appropriate for that

matter, to make predications on the result of such a ‘detour’ in the journey of

his works, which still has a long way ahead of it.

In

conclusion, salvation will come from beauty. But beauty is not achieved only

with something enjoyable and sleek for the eyes. Without the endurance of time

and memory, decomposition will follow. Memory is the record of intense

concentration, and without this kind of commitment, traces would be blurred,

memories scattering away. I anticipate more profound maturation from Hyungkoo

Lee’s works.