For

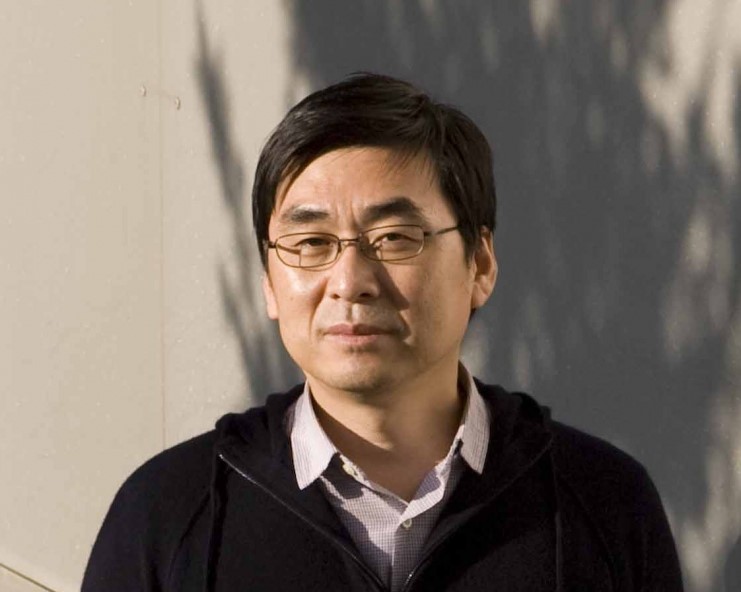

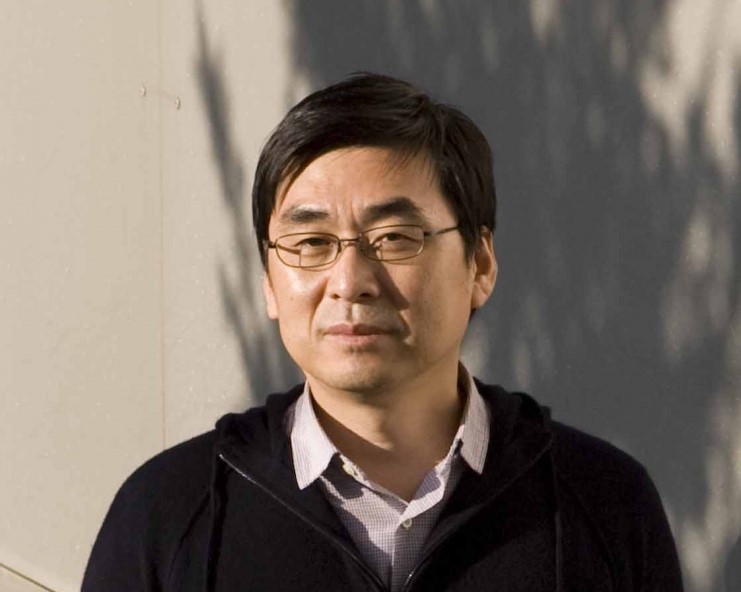

the exhibition at PLATEAU in the summer of 2014, Inhwan Oh produced the

project Guard and I, a work that unveils the tension

between individual identity and social norms, critically examines the

institutional order of a museum, and exemplifies Oh’s persistent attempts to

communicate with others on an intimate level, even if the relationship is temporary.

Guards

are present in every museum, but they are very inconspicuous; in fact, even

though our eyes see them, they are invisible. While museum visitors are

entirely focused on the exhibited works, the guards’ duty is to screen the

visitors who are looking at the works. Through the guard, the visitors change

from “seeing the subjects” to the “seen objects,” or more precisely, from the

“watcher” to the “watched.”

Inhwan

Oh, who has entered many museums as a visitor, considers the guard to be one

axis of the social power structure that observes individuals, indirectly

recalling Foucault. In particular, the guards at Plateau Gallery are always

young men, sharply dressed in fine suits, equipped with earpieces, and armed

with a very polite yet stern attitude. Accordingly, under their “surveillance,”

the visitors implicitly conform to the order enforced by the museum.

However, when someone like Inhwan Oh, whose works are displayed in the gallery,

enters the space, the power structure is inverted. There are three basic levels

of labor taking place in a museum: the labor of the artists, which is elevated

to a nearly divine level in the name of “creation”; the labor of the curators,

which is contained within the specialized scholarly domain; and the labor of

the guards and custodians, which is regarded as simple manual labor with no

added value. Hence, as an artist, Inhwan Oh occupies the highest position, not

only in the museum, but apparently on the ladder of class and labor that

pervades the entire society.

In

addressing this complicated hierarchy, Inhwan Oh aims to change the entire

system by exposing the layers of cultural meaning that exist between his role

(simultaneously a viewer and the artist) and that of the guards. While

producing the work, Oh devised a project that he could do together with the

guards of Plateau Gallery, and he thus proposed a very ordinary and simple

“meeting” for that purpose.

In

seeking to contextualize this work, we must first acknowledge the tradition of

critiquing the institution of the museum, a fundamental concern of the

neo-avant-garde since the 1960s. The representative figure is the American

performance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939), who cleaned the museum as

performance, calling it “Maintenance Art.” But while Ukeles primarily worked

independently, Inhwan Oh required the active and voluntary participation of the

actual guards. Given that he interacted with the guards and attempted to form

some relationship with them, his work may also be connected to “Relational

Aesthetics” or “participatory art,” in a more contemporary sense.

It

has already been some time since relation, participation, and communication

became the most representative keywords for defining the working methods of

contemporary art. Today, these words sound rather conventional and vapid, but

they acquire concrete and substantial significance in Oh’s works, because they

do not invoke any grand social discourses, nor do they serve as simple abstract

slogans or overly optimistic prospects.

What

can guards and an artist do together in a museum? But before they can do

anything, shouldn’t they get to know each other a little bit first? With this

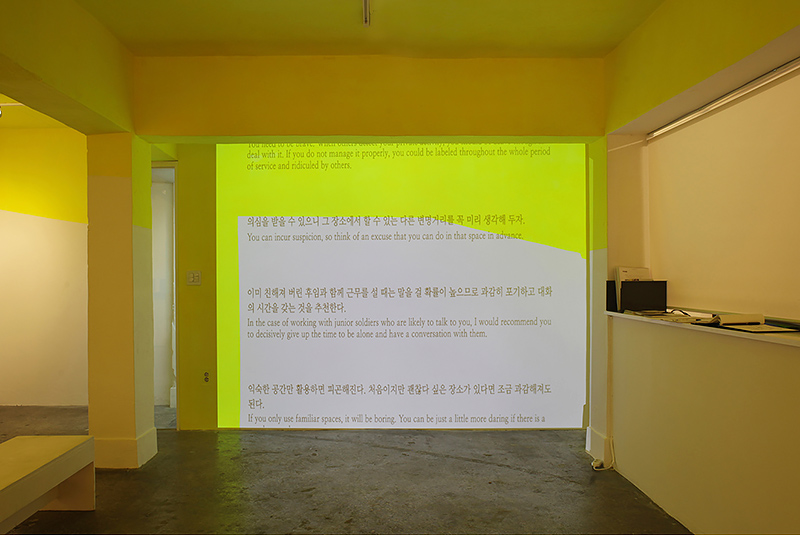

in mind, Inhwan Oh notified the guards of Plateau Gallery of his intentions and

the goal of his work, and one guard finally agreed volunteered to participate.

Oh and the guard agreed to meet ten times; after each meeting, the guard could

decide whether or not to continue the meetings. For their first meeting, they

had tea together, the standard ritual for any two people who are thinking of

building some kind of relationship. In their second meeting, they became more

comfortable talking and sharing their stories with one another, and in their

third meeting, Oh invited the guard to his studio and showed his works.

The

original plan was that, after the ten meetings, Oh and the guard would dance

together at the museum. If the plan had been realized, it would have been a

legendary event that would resonate in the history of Korean contemporary art:

an artist and a security guard met many times outside the museum, came to

intimately understand each other, and finally danced together in the museum.

Though perhaps this storybook ending would have felt a little mundane in the

environment of contemporary art, where, with the aid of “aesthetics,” themes of

relation, participation, and communication have automatically become the object

of superficial sentimentality and admiration, regardless of the actual

contents.

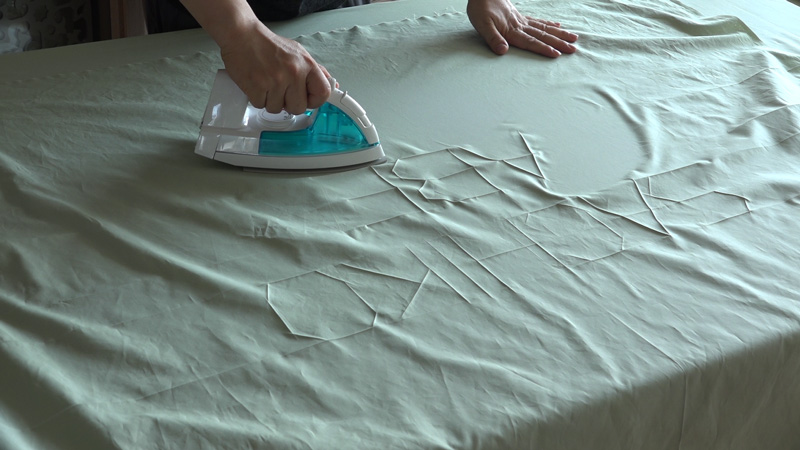

In

Oh’s work, however, the dance was not meant to be. After the third meeting, the

guard declined to continue, bringing an end to the project. Inhwan Oh was left

to waltz alone at the museum, spending the two months before the event

diligently learning the dance with a private instructor. He danced in front of

CCTV cameras, which stand in when guards are not present. As such, Inhwan Oh as

an artist became the one who is “surveilled” in a museum, but at the same time,

the tool of surveillance became the work itself. Through this process, the

boundary between surveillance and appreciation disintegrated.

In

fact, the true achievement of this work lies in the failure and incompletion of

the process. Like Lee’s previous works (Where Man Meets Man,

Things of Friendship, Lost and Found, and Meeting Time), Guard and I exemplifies

the fact that questions of identity—namely, the tension from “differences”

between me and others and the conflicts that individuals face because of social

norms—can never be reduced to homosexuality. Thus, in trying to determine the

true reasons why the project was interrupted, viewers are left with many layers

of speculations and inferences.

In

the final work, each meeting between Lee and the guard was to be documented

with a booth. But since the final seven meetings were not realized, the work

includes seven empty booths. It is never easy for a person to participate in

actions that violate the codes of one’s occupation and social status. Even with

good intentions and just cause, “relation” cannot be formed in a short time.

Likewise, perfect “communication” cannot be achieved through the steps of a

waltz that one has learned through rote practice over only a few months. As

such, the seven empty booths represent a profound question about art’s capacity

for social criticism. I hope that the exhibition of the 《Korea Artist Prize 2015》 offers Inhwan

Oh the opportunity to somehow fill in those seven booths. But even if they

remain empty, I am certain that the artist will fill the space with more

questions and thoughts.