As

in the 2011 MMCA exhibition 《Stories of 23

Artists of the Year 1995–2010》, Park’s works featuring

colored vinyl curtains fluttering like drapes also appear in many large-scale

exhibitions. These works trace back to his Volume installation

at Melbourne’s Centre for Contemporary Photography in 1997, which used

colorless transparent vinyl. “I think the appearance of the space where the

work is installed is as important as the work itself. For that reason, the work

must not damage the given space. I wanted to realize the space with minimal

form. I wondered what medium would best achieve this, and I thought of thin,

transparent vinyl.”

From

the exhibition at DDP in 2015, to the 30th Anniversary Special Exhibition 《The Moon is Waxing, Waning, and Eclipsed》 at

the MMCA Gwacheon in 2016, to the solo exhibition 《Growing

Space》 at 313 Art Project, the 2018 OCI Museum of Art

exhibition 《And Said Nothing》,

and now Red Room at 《Continuity》. Park’s colored vinyl works illuminated by LED lighting have become

his signature series, demonstrating the perfect coexistence of work and space.

Among

these, the work many remember is Sunshine, presented

at 《Esprit Dior》 at DDP. In

this exhibition, which featured six representative Korean artists including Do

Ho Suh, Lee Bul, and Kim Heyryun, Park created a dreamy installation of pink

and red vinyl illuminated by LED lights, combined with his ‘Width’ series hanji

paintings, to evoke Christian Dior’s world of charming colors. “Four years have

passed, but I still feel a deep satisfaction when I think of that exhibition.

Dior’s Paris headquarters directly handled the show, and I felt the process was

very sophisticated. Their consideration for artists to focus on their work was

impressive. The six artists’ works came together harmoniously thanks to the

curator’s ability.” Dior’s keyword for him was “from pink to red.” With all

shades of pink cascading like a waterfall against the tall ceilings of DDP, the

work rustled and danced as visitors passed by, offering audiences another

chance to reflect on the vital interplay between contemporary art and space.

Park’s

relationship with Parisians, which he recalled as “sophisticated,” continued

the following year in 2016. He had the opportunity to install a 10-meter steel

structure titled Flash Wall, expressing wishes for

peace and reunification, on the façade of the Grand Palais during Art Paris.

Made of interwoven wires flanking the entrance to the Grand Palais, the work

carried a message of solace for the scars of terror in Paris and of peace. His

bold gesture, adorning the entrance of the Grand Palais—a venue for exhibitions

by artists like Anish Kapoor, Christian Boltanski, and Daniel Buren—was quietly

but widely shared through art journalism and the social media of visiting

tourists.

As

anyone who has experienced Park’s exhibitions can easily imagine, most of his

works are site-specific. Unlike artists who rely on steady labor grounded in

daily routine, Park’s process of hurried preparation begins only once an

exhibition is confirmed. One wonders about his everyday life. “Even though I do

space works, on days without installation schedules, I like to take my time

painting. Especially on hanji. I also spend my days making small sketches or

noting down new materials or methods. Once an exhibition space is set, I

consider the nature of the site and refer to past sketches or notes.”

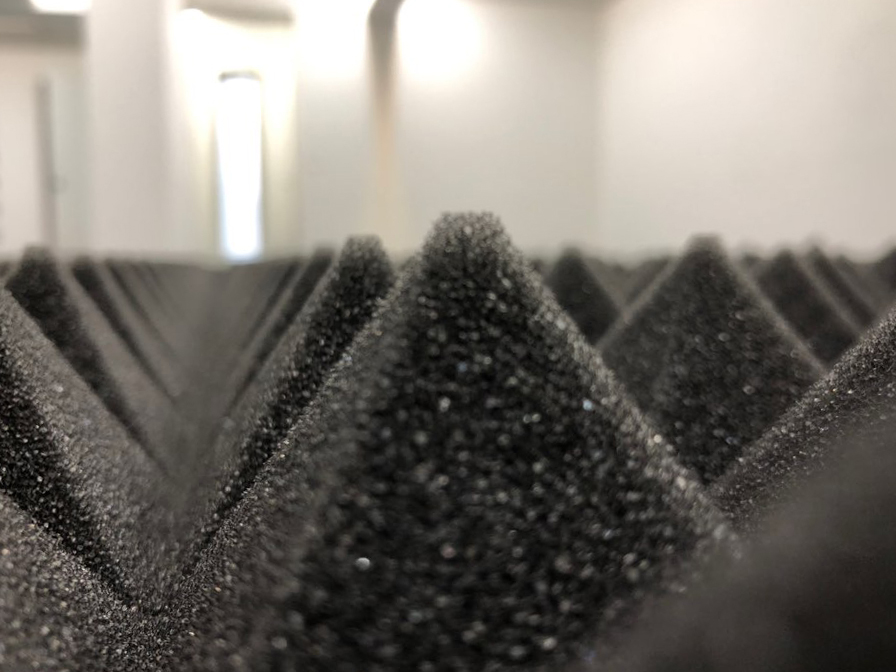

The

《Continuity》 exhibition

held at 313 Art Project, located in a residential alley in Seongbuk-dong, is a

reflection of such ongoing musings. The pyramid-shaped black sponge floor

filling the first-floor gallery was an idea he had long been interested in.

Wishing to create a piece that would let visitors feel as though resting in a

grassy field, he cut black sponge into finger-length pyramids and spread them

across the entire floor. Visitors changed into slippers or wore only socks at

the entrance and experienced new tactile sensations by stepping on the spongy

pyramids. Standing, walking, and sometimes sitting on the floor, they observed

one another and discovered new landscapes shaped by space. “I always hope my

works appear like backgrounds. So when I work, I keep in mind situations where

works and people are intermingled. Rather than the cliché of ‘a work hanging on

a wall with a spectator standing before it arms crossed,’ I think about how

both works and viewers can become protagonists together.”

Considering

the gallery’s unusual circulation—retaining the structure of an old

Seongbuk-dong house rather than a pristine white cube—Park devised diverse

spatial arrangements. “The overall circulation here is unique, especially the

long distance from the gallery gate to the exhibition space. I wanted the first

piece viewers encountered upon opening the gate to give a hint about what would

unfold inside. So I installed Disappear Entrance,

covering the passage from the gate to the main building entrance with

jade-colored FRP boards.”