The Korean art market has experienced significant peaks and troughs approximately every ten years since the 1970s. This article explores the first wave.

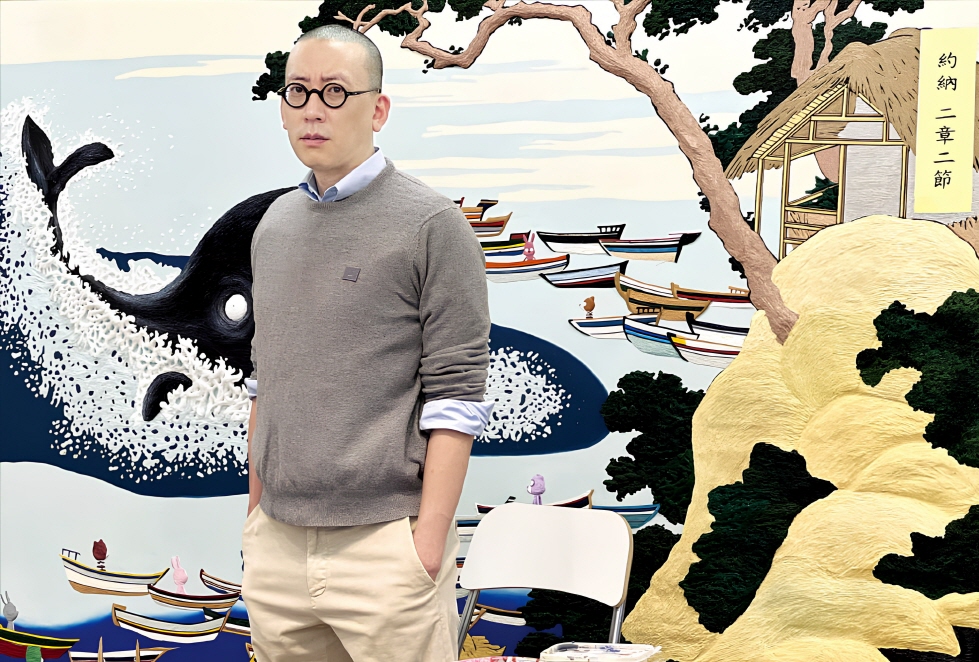

Kiaf SEOUL 2023. Photos by Kiaf SEOUL Operating Committee. Courtesy of Kiaf SEOUL.

Kiaf SEOUL 2023. Photos by Kiaf SEOUL Operating Committee. Courtesy of Kiaf SEOUL.In recent years, despite a downturn, there has been a surge of interest in the art market in Korea. For instance, the Korean art fair Kiaf SEOUL, held in early September, attracted around 80,000 visitors, 15% more than last year’s 70,000 visitors.

This heightened interest can be attributed to the growing focus on art as an investment. However, understanding the market requires a diverse range of knowledge. In that sense, it’s important to understand the history of the Korean art market and its unique patterns to have insight into the future market can be achieved through knowledge of the past art market.

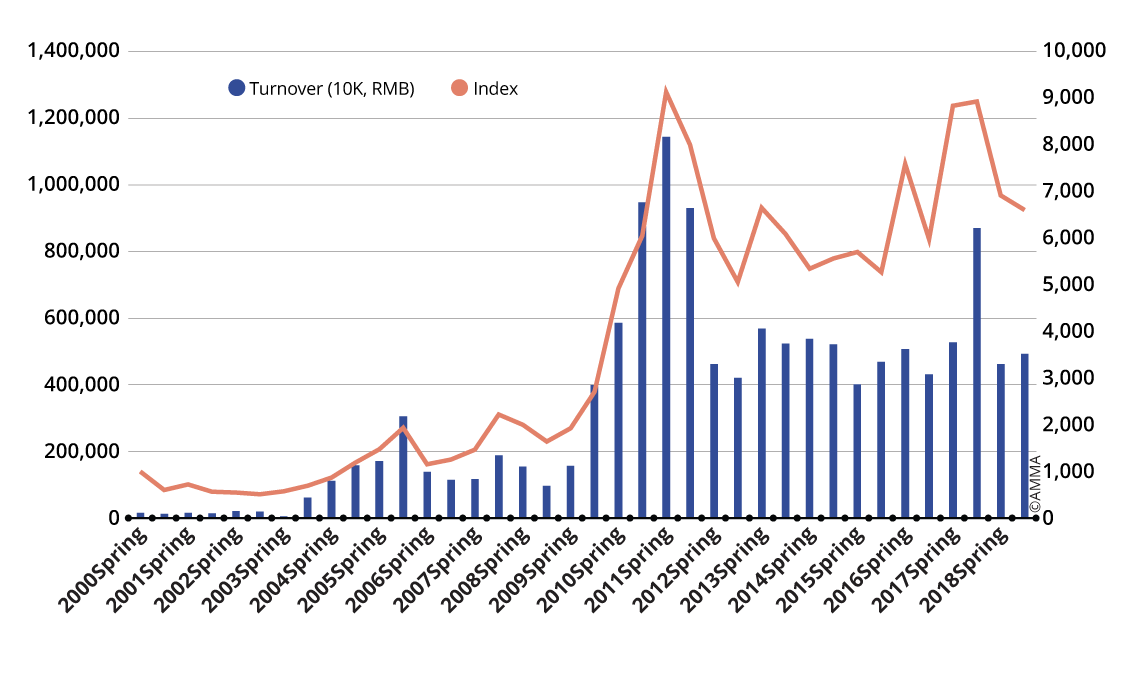

The Korean art market has experienced significant peaks and troughs approximately every ten years since the 1970s, when the structure of the art market as we know it today was established, a time when art increasingly became recognized as a commodity. These peaks occurred in the late ‘70s; the late ‘80s to early ‘90s; the mid-2000s, particularly around 2007; and most recently in 2021 when the Korean art market reached its peak, it currently being in an adjustment phase.

The sign in front of the relocated Ministry of Culture and Communications building in 1986, Seoul. ⓒeHistory.

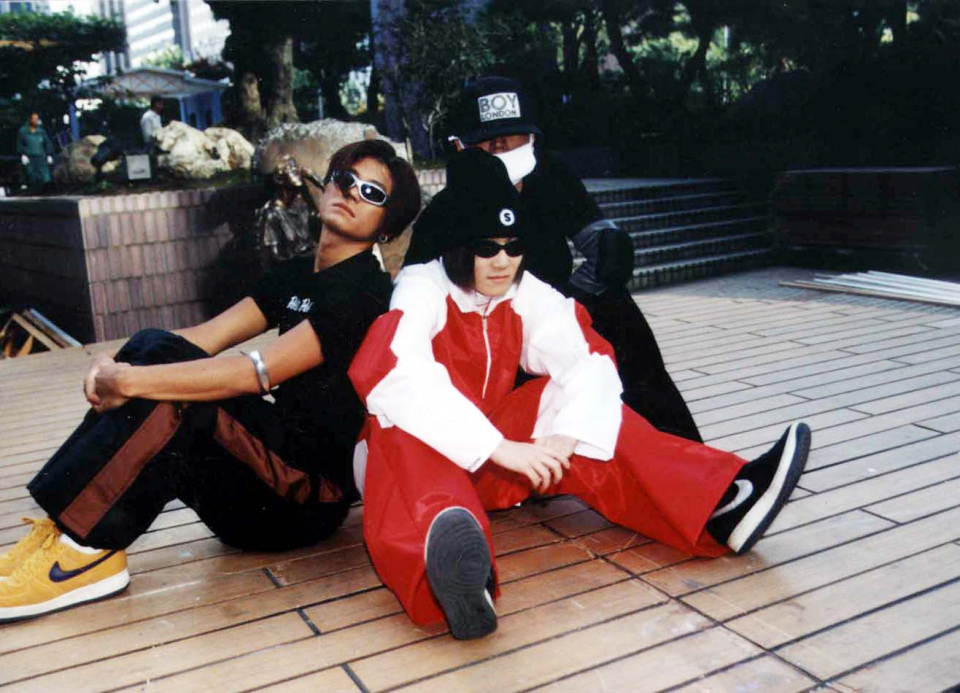

The ‘70s, the beginning of the shift in the ark market, were a time of significant economic expansion in South Korea. The country experienced rapid economic growth, driven by the Five-Year Plans for Economic Development. While the authoritarian government often used cultural and artistic endeavors as tools for maintaining its regime, shaping national identity, and promoting modernization, this era also brought about considerable changes in the Korean cultural and arts scene.

On a governmental level, the Ministry of Culture and Communication was established in 1968, and in August 1972, the Cultural and Arts Promotion Act was enacted. In 1974, the First Five-Year Plan for the Advancement of Arts and Culture (1974-1978) was devised, allocating 2.5 billion KRW to the cultural and arts sector. This budget, although primarily aimed at traditional cultural arts, also supported various other domains, such as contemporary art, music, film, publishing, and literature. This expansion included increasing cultural facilities to enhance cultural activities for artists and audiences.

During the early ‘70s, modern-style galleries began to emerge in South Korea. A key player in this transformation was the Hyundai Hwarang (now Gallery Hyundai), established in Insa-dong by Park Myung-ja and Han Yong-gu. The gallery played a significant role in brokering modern and contemporary art in South Korea. Economic growth fostered an emerging bourgeoisie, and as money flowed in, additional galleries began to form around the Insa-dong area in Seoul.

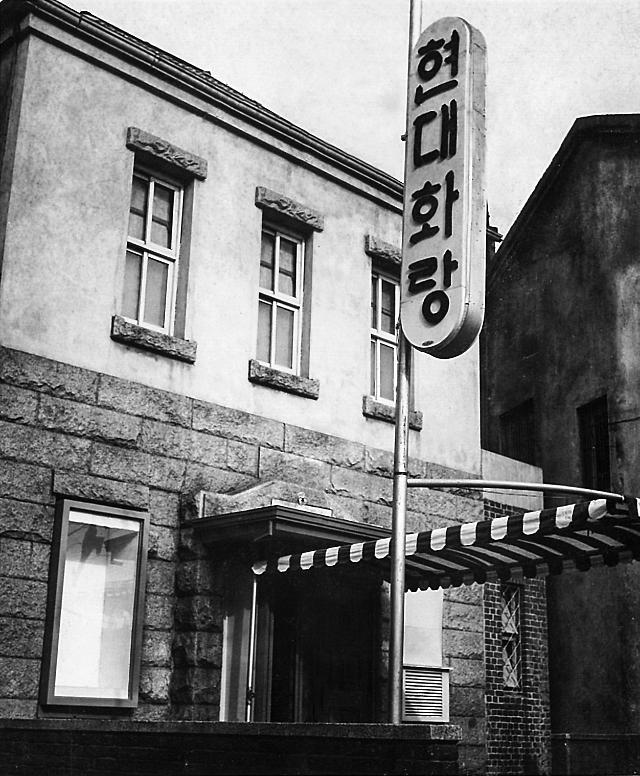

Exterior view of Hyundai Hwarang (current Gallery Hyundai), Seoul. Courtesy of the gallery.

Exterior view of Hyundai Hwarang (current Gallery Hyundai), Seoul. Courtesy of the gallery.The modern art market is not just about supply and demand. In order for it to function, a slew of people and entities must coalesce, including artists who create artworks, collectors who enjoy them, and art institutions, galleries, critics, and curators who assess the value of these works.

This period saw the emergence of art critics, an important role in the art market. Numerous publications related to art and art criticism were founded in the 1970s. Through magazines like Gyegan Misul (Quarterly Art), Misulgwa Saenghwal (Art and Life), Design, and Misul Chunchoo (The Art Years), critics became more active, laying the groundwork for a structural foundation in the Korean art market, albeit in a selective manner.

It was with the opening of the Hyundai Gallery that galleries specializing in works by contemporary artists began to appear, including the Myeongdong Gallery (1970), Seoul Gallery (1970), Chosun Gallery (1971), Jin Gallery (1972), Dongsanbang Gallery (1976), Sun Gallery (1976), and Songwon Gallery (1977). Relatedly, in 1976, 12 galleries formed the Korea Art Galleries Association, which grew to 26 members by 1978. In all, from the late ‘70s to the early ‘90s, galleries held 50,000 to 60,000 exhibitions, accounting for nearly 90% of the total exhibitions, including in public institutions.

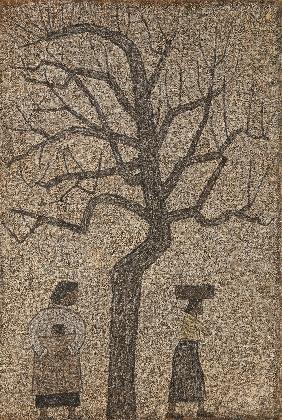

Park Soo Geun, ‘Tree and Two Women (나무와 두 여인),’ 1962, Oil on canvas, 130 x 89 cm. Leeum Museum of Art Collection.

However, with the rise in gallery activity, the prices of works that were affordable in the 1960s skyrocketed in the ‘70s, and people began to view art as an object of speculation.

At the time, a typical office worker’s monthly salary was 400,000 to 500,000 KRW, and the annual budget for acquiring artworks at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 1976 was 10 million KRW. The art market was in an overheated state at the time, evinced by transactions such as popular ‘70s traditional Korean painter Lee Sang-beom’s Sanshou painting going for up to 20 million KRW.

The newly wealthy, emboldened by recent economic development, began to hoard artworks as their prices skyrocketed. Largely, however, the mainstream of the art world still encompassed traditional Korean paintings, and the preference for modern or Western art was relatively low.

This changed in the late ‘70s, when demand for modern artworks and Western paintings, mainly oil paintings and semi-abstract works, increased. In particular, abstract works that incorporated Korean elements gained attention. Artists such as Park Soo Keun, Lee Jung-seob, Kim Whanki, Byun Jong-ha, and Kwon Okyeon became popular. By 1978, Park Soo Keun’s works were priced at over 1 million KRW, Lee Jung-seob’s at 2 million KRW, and Kim Whanki’s at 300,000 KRW.

Lee Jung-Seob, ‘White Ox,’ 1954, Oil painting on wooden panel, 30cm × 41.7cm, Hongik University Museum Collection, Seoul, Korea.

Due to these converging factors, in the late 1970s, South Korea experienced its first art market boom. Art transactions were so active that works of art were even traded in coffee shops and clothing stores. However, this art market boom came to an end in 1979 when tax investigations were conducted on galleries.

The 1970s were a pivotal time for the Korean art market, as the period marked the establishment of a modern, structured market. However, during this period, there was a lack of awareness regarding the importance of systematically establishing the prices for art works. This led to many artists engaging in direct sales to collectors without gallery representation. Furthermore, at this time, Korea lacked auction houses capable of determining prices based on the value of the artwork, which resulted in prices being primarily determined by the work’s size.