Inhwan Oh (b. 1965) has been working on performance, installation, and site-specific projects that require a specific time and space rather than conventional art forms or the production of material, permanent works. In addition, based on his real-life experiences regarding his own queer identity, Oh deconstructs or reinterprets individual identity and group relationships in a patriarchal society and the cultural codes that have been formed as a result, while incorporating keywords such as difference, diversity, and communication into his works to connect with everyday experiences.

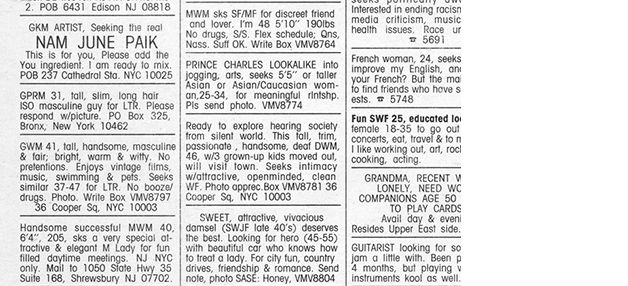

Inhwan Oh, Personal Ads, 1996 ©Inhwan Oh

In 1996, Oh introduced himself as a

GKM (Gay Korean Male) artist in ‘The Village Voice,’ a weekly newspaper

published in New York City, and placed a personal ad for five artists, Roni

Horn, Robert Gober, Nam June Paik, Haim Steinback, and Cindy Sherman. While

personal ads looking for someone were common at the time, the addition of the

word “real” to the description of these world-renowned artists, who are not common

names, makes the sentence meaningful.

This is not limited to specific

artists, but leads to the question of identity: “Who and what is real?” And if

there is a real person to be found here, it is not these five artists, but the

artist himself. In this work, the artist openly identifies himself as a “gay

Korean male artist” (GKM Artist), aligning his creative process with his

personal experience of coming out.

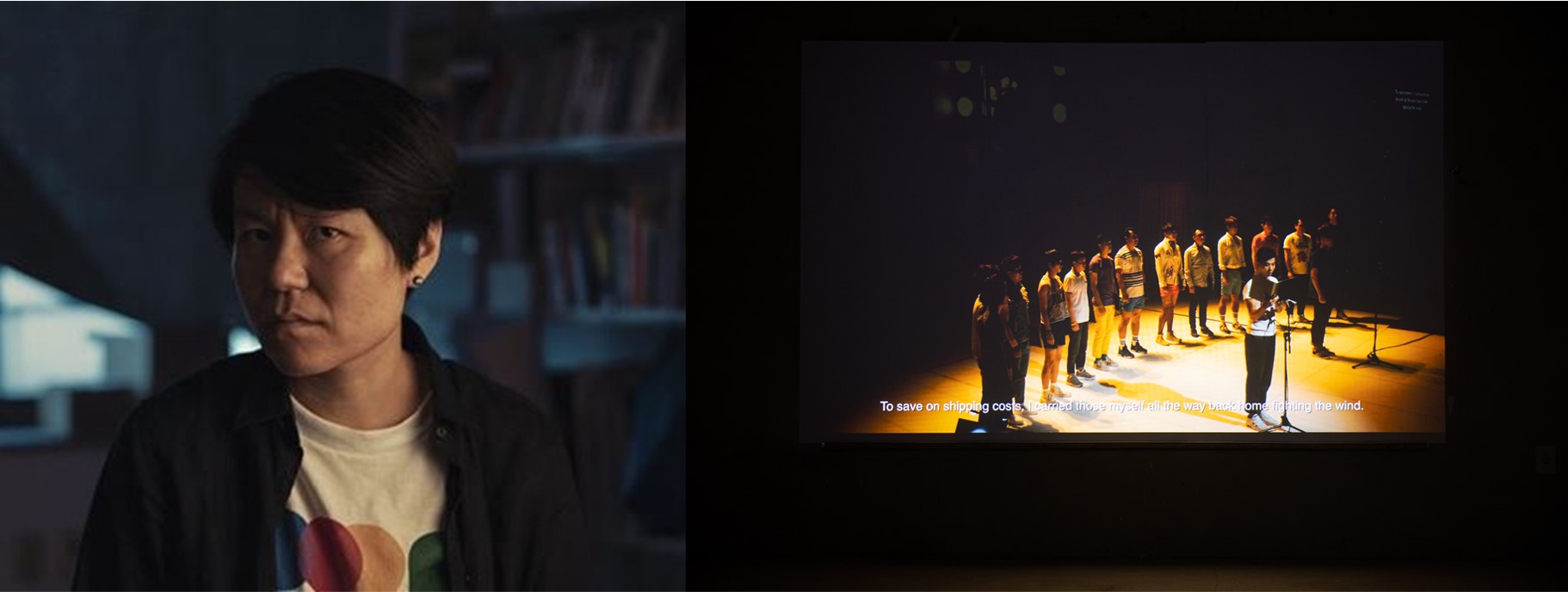

Inhwan Oh, Meeting Time, 1999-present ©Inhwan Oh

Inhwan Oh has been interested in

revealing personal identities based on his own real-life experiences, as well

as the social context and cultural codes that are intertwined with them, and

has been experimenting with how these stories can be read and communicated to viewer

in the current context. As such, Oh's project takes on the character of an

unfinished project that continues through photographic documentation focused on

the 'here-and-now'.

For example, Meeting Time

(1999-) documents the artist's encounters with people living in various

countries by photographing their wristwatches side by side. Although the two

watches in the photographs were taken at the same time, they are set to

different local time zones, so they record the encounter at different times.

In other words, the two watches in

this work record the encounter as 'difference' rather than sameness. The artist

then turned the photographs into postcards and stacked them on the floor of the

exhibition hall, asking the viewer to send their favorite postcards to the

artist. However, the postcards that disappear from the exhibition and the ones

that arrive at the artist are not exactly the same, creating another

'difference' through the viewer's participation.

Inhwan Oh, Where He Meets Him, 2001-present ©Inhwan Oh

Where He Meets Him,

presented since 2001, is an installation in which the names of gay bars and

clubs scattered around the city where the exhibition is held are collected and

written in incense powder on the exhibition floor. Ignited at the beginning of

the exhibition, the work slowly burns down over the course of the exhibition,

highlighting the names of gay bars and clubs that have turned to ash.

For those familiar with these queer

communities, the meaning will be readily apparent, but for those who are not,

it will read as a collection of unfamiliar words that are difficult to

decipher. As the words burn and turn into odors, the work becomes unfixed,

spreading into space beyond the physical boundaries of the work itself, and

even into the viewer's body.

Inhwan Oh, Security Guard And I, 2014 ©Inhwan Oh

In 2014, he conducted an experiment on

the socio-cultural surveillance system through collaboration. Security

Guard And I documents the process of 'personal friendship'

between a security guard and an artist, who are separated by their personal

identities and social roles within the same space of an art museum. The artist

and the museum security guard met once a week after work outside the museum and

bonded over meals, exercise, and other things they could do together.

The process could end whenever the

participant (the guard) wished, and if it continued to the final stage, the

artist and the guard would perform a dance together in the museum, which would

be recorded by surveillance cameras. However, the project was eventually

aborted after three meetings, and the artist ended up dancing alone.

Security Guard And I

was a collaborative project that started with the premise that there is a

socio-cultural surveillance system that operates according to the occupation,

role, gender, and sexual identity of individuals in a society, and invited the

security guard and the artist to collaborate on an experience beyond the

surveillance system that operates inside and outside the museum. Conventional

surveillance devices (surveillance cameras) are transformed from their original

surveillance function into an artistic means of recording and sharing this

collaboration with the audience.

Inhwan Oh, Looking

Out for Blind Spots – Reciprocal Viewing System, 2014 ©MMCA

Inhwan Oh, Looking

Out for Blind Spots – Reciprocal Viewing System, 2014 ©MMCASelected

as the artist of the ‘2015 Korea Artist Prize’ by the National Museum of Modern

and Contemporary Art Korea, Inhwan Oh presented his project Looking Out for Blind Spots expanding on his personal

narrative of socio-cultural surveillance. The artist believes that in any

society, there is a cultural power that operates to make people accept the

dominant value system, and that individuals secure their safety as members of society

by constructing their roles, identities, and desires to conform to the dominant

values.

However,

rather than fully conforming to such cultural power, individuals often seek out

'blind spots' as alternative areas where they can realize their unacceptable,

othered desires, and from here, various cultures that are excluded from the

dominant culture are created.

For this

reason, the Looking Out for

Blind Spots project

was initiated to signify 'cultural blind spots' as the place where diverse

cultures that are not allowed by the dominant culture flourish and to reveal

that cultural blind spots are not an ideological concept but an everyday

reality through examples of individuals' various blind spots in their daily

lives.

As a

cultural blind spot is a fluid form of occupation, the artist's project has

site-specific features that are transformed or reinterpreted according to the

conditions of the exhibition and venue. The project Looking Out for Blind Spots is composed of individual

entities and each project is interconnected as independent projects.

Inhwan

Oh's various projects are completed through the participation of the audience.

As a member of society, every individual, including the artist, is bound to

live within the socio-cultural surveillance system and find their own cultural

blind spots within it. The artist makes the everyday life of such reality

visualized and signified through the art and presents his work as a way to

escape from existing social universality and dominant rules.

“As

an artist, I think it is important to be able to reveal one's position or

attitude, so I thought it was important to reveal my position as a cultural and

institutional critic. I think it's my job as an artist to keep waking up (...)

In contemporary art, I don't think we meet the audience when the work is

finished, but the audience comes and completes the work.

I

make a work with the participant in mind, but it doesn't go as I expect, and I

don't know what form it will take. I want the audience to actively respond to

what's going on in their minds because they are the ones who end up creating

the work.” (Interview with Inhwan Oh at the MMCA’s

2015 Korea Artist Prize)

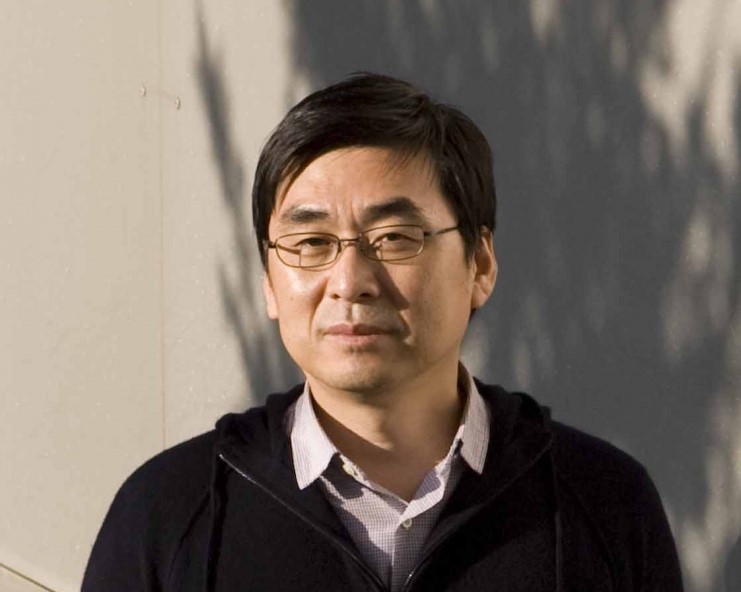

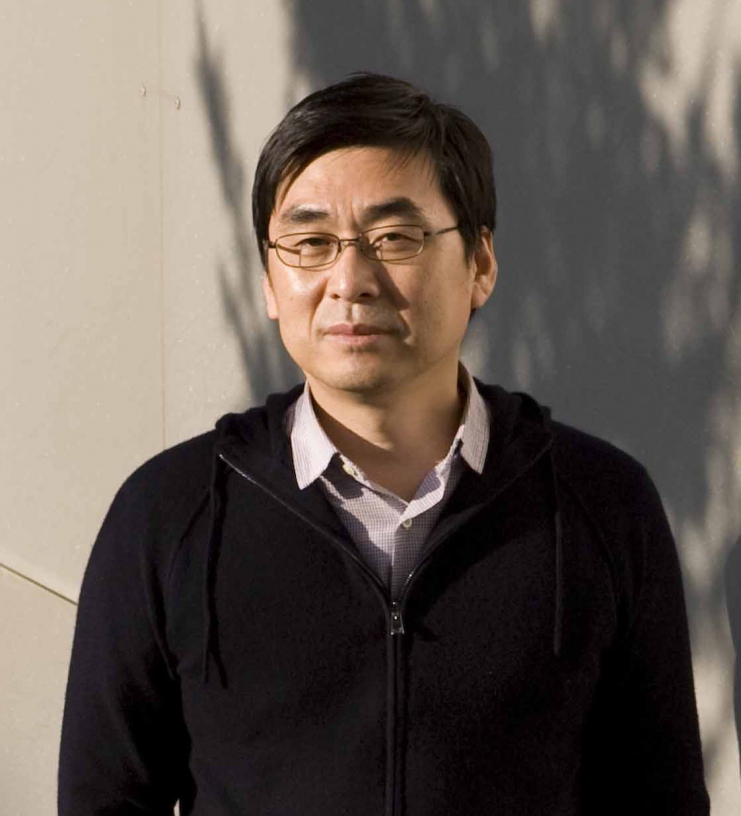

Artist Inhwan Oh ©Seoul National University

Inhwan

Oh studied sculpture at Seoul National University and graduated from Hunter

College Graduate School in New York. He has held solo exhibitions in Korea and

abroad at various institutions such as Commonwealth & Council/ Baik Art

(Los Angeles, U.S.A., 2019), Space Willing N Dealing (Seoul, 2018), Art Sonje

Center (Seoul, 2009), Mills College Art Museum (Oakland, U.S.A., 2002), and

Project Space Sarubia (Seoul, 2002).

He has also participated in group exhibitions at

the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (Seoul, 2024), Navy

Officer's Club in Arsenale (Venice, Italy, 2019), Nam-Seoul Museum of Art

(Seoul, 2017), Kyoto Art Center (Nijo-Castle, Kyoto, Japan, 2017), and Plateau

(Seoul, 2014). He is currently a professor at the Seoul National University

College of Fine Arts and was selected as the artist of the 2015 Korea Artist

Prize by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea.