Understanding the international influences on Korean experimental art is vital, as it will illuminate the unique position Korean experimental art occupies on the international art stage.

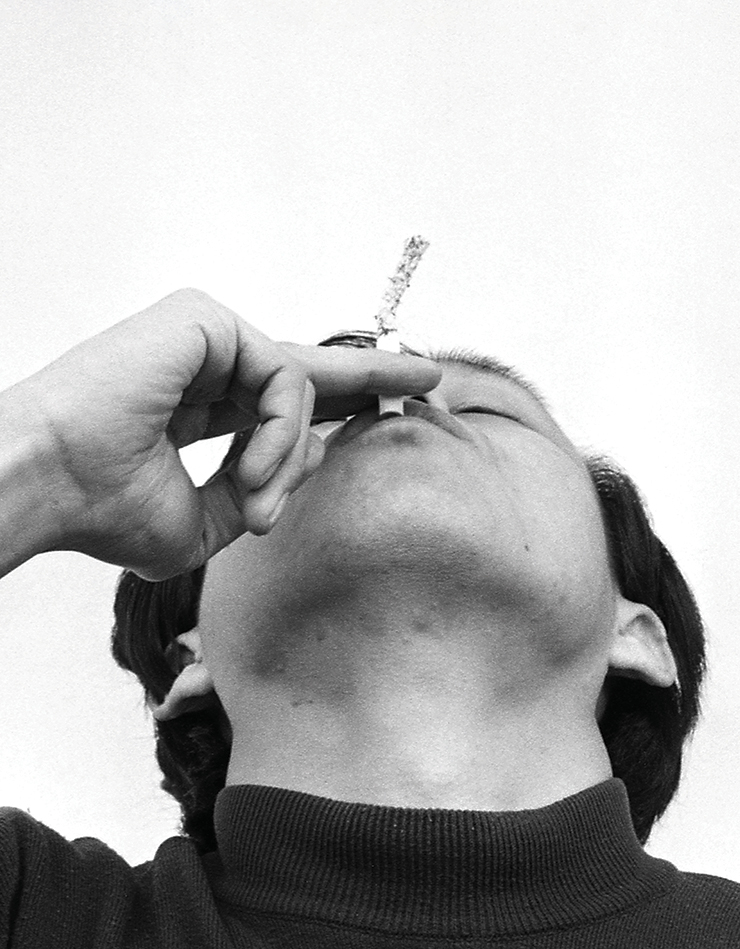

Jung Kangja, 'Kiss Me,' 1967/2001. Mixed media, 47 1/4 x 78 3/4 x 9 11/16 in. (120 x 200 x 50 cm). ARARIO collection. © Jung Kangja/ARARIO Collection, courtesy Jung Kangja Estate and ARARIO Gallery. Photo: Han Junho.

Jung Kangja, 'Kiss Me,' 1967/2001. Mixed media, 47 1/4 x 78 3/4 x 9 11/16 in. (120 x 200 x 50 cm). ARARIO collection. © Jung Kangja/ARARIO Collection, courtesy Jung Kangja Estate and ARARIO Gallery. Photo: Han Junho.From the mid-1960s to the early 1970s in Korea, a diverse range of art activities unfolded, utilizing various mediums beyond traditional painting and embracing performance art. However, these art movements could not be categorized under a single trend for a considerable time. As a result, the Korean art scene referred to this period as a “transitional” or “chaotic” phase.

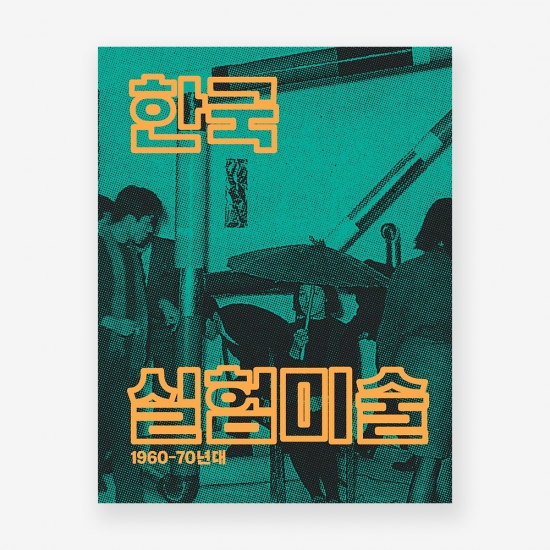

The era of Art Informel painting, spanning from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, and the subsequent Dansaekhwa or monochrome painting period of the 1970s, have been subjects of relatively extensive research in Korean modern and contemporary art history. In contrast, it was not until the 2000s that Korean experimental art began to gain recognition as a distinct movement.

Art Informel, as the dominant abstract art movement in post-war Europe, rejected geometric abstraction in favor of spontaneous actions and passionate expression by artists. This movement garnered significant attention in Korea for about a decade, starting in the late 1950s. Nevertheless, as all movements do, the once-dominant influence of Art Informel on the Korean art scene began to fade.

By the mid-1960s, younger artists, tired of the uniform art atmosphere fostered by Art Informel, shifted their focus to anti-painting art forms.

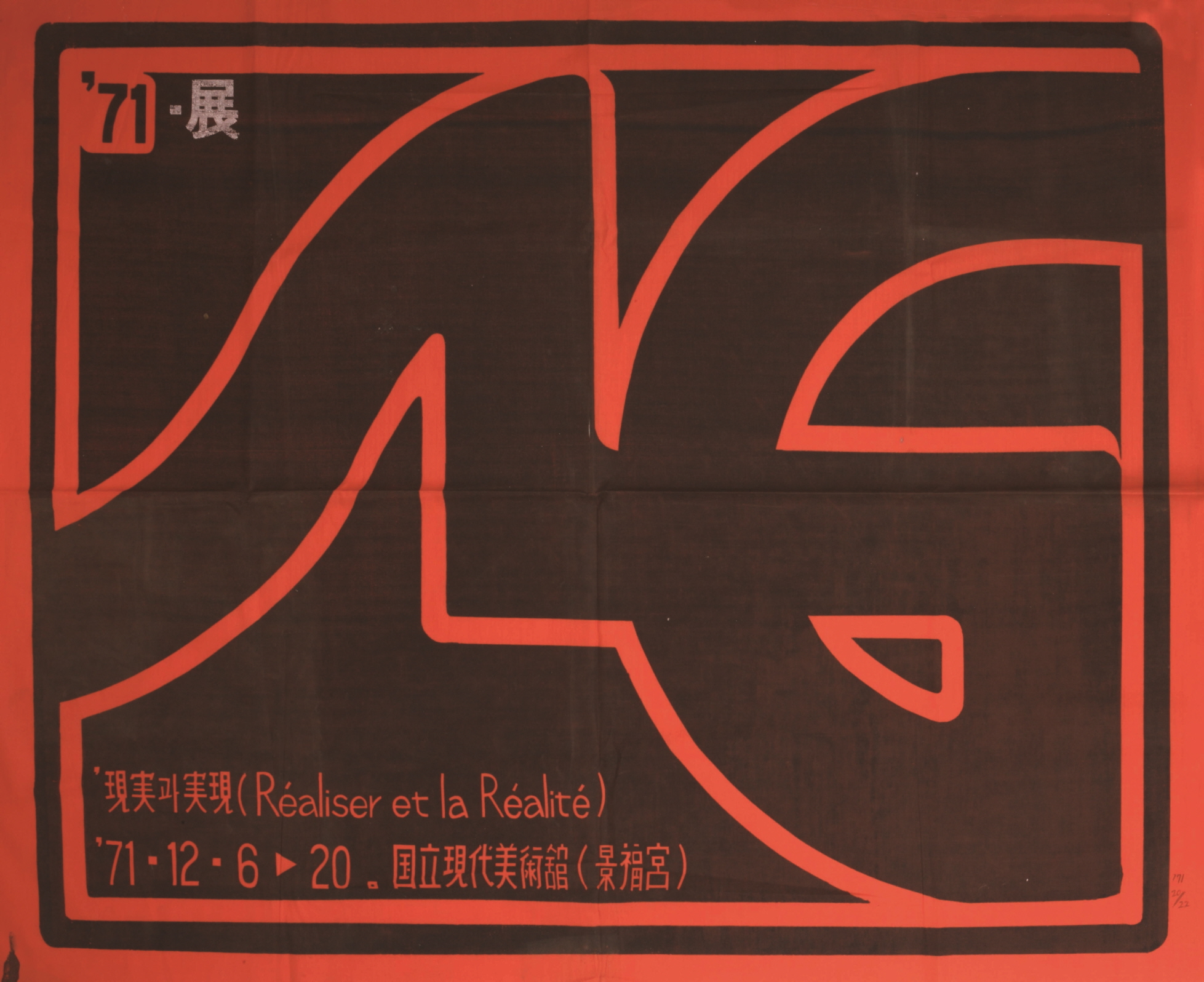

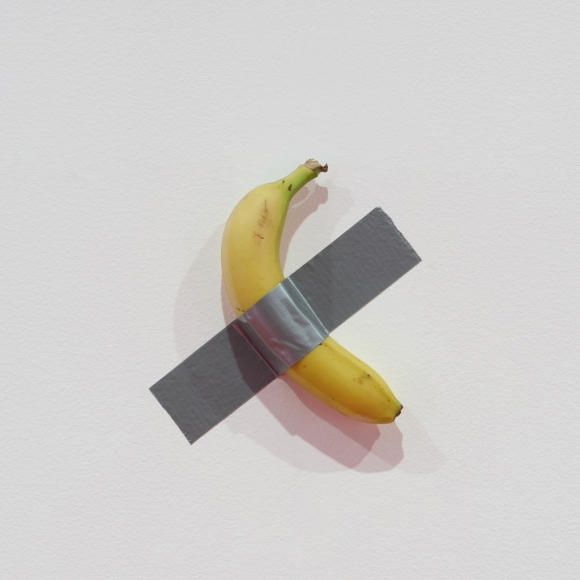

1-3. Lee Kun-Yong, 'The Method of Drawing 76-2,' 1976. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Lee Kun-Yong. Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

These experimental artists found inspiration in happenings, events, land art, conceptual art, and object art taking place in Western cultural spheres and Japan. As a result, they dived into the creation of works that were conceptually compelling. Among them are Lee Kun-Yong’s paintings utilizing arm movements, a performance symbolizing the funeral of Korean art, and Lee Seung-taek’s Wind, in which he suspended a blue cloth more than 100 meters between buildings, employing wind as an artistic medium.

While these pieces emerged from Korea’s unique context, much like Art Informel was shaped by European abstract art movements, Korean experimental art bore the imprint of global artistic trends. The influence of Japan, in particular, is noteworthy.

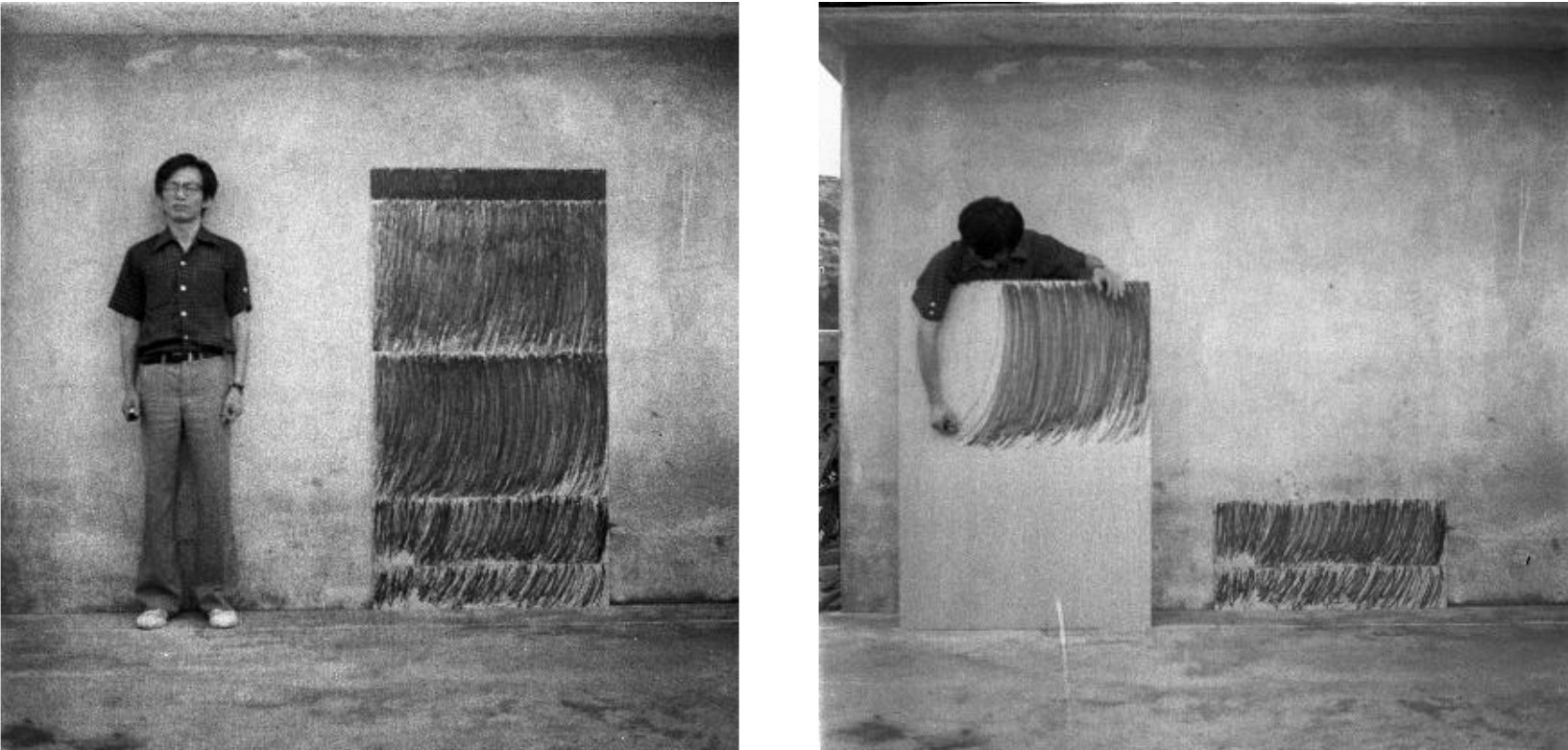

During that era, Korean artists participated in international biennales such as the Paris Biennale and the São Paulo Art Biennial, gaining exposure to new Western art trends. Yet, for the majority, their window to international art was through Japanese magazines such as Bijutsu Techo (美術手帖) and Mizue (みずえ) or American magazines such as LIFE and TIME, which were available through US military bases.

One of the covers of Monthly Art Magazine 'Bijutsu Techo.' © Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha, 美術出版社 (Tokyo, Japan).

Korea and Japan have complex political and historical relationships, which led contemporary experimental artists and critics to avoid discussing the influence relationship between Japan’s avant-garde art and Korean experimental art. However, Korea effectively acquired and embraced global art through Japan’s information networks like Bijutsu Techo and Mizue. Art historian Park Misung suggests that during the late 1960s, Korea indirectly absorbed Western contemporary art through Japan rather than directly encountering it.

Korean experimental art embraced Italy’s Arte Povera and America’s Conceptual Art largely through Japanese influences. Arte Povera, meaning “poor art,” was a movement in which artists explored a range of unconventional processes and nontraditional “everyday” materials. This movement found parallels with process art, conceptual art, and environmental art, garnering recognition as an international trend. Meanwhile, Conceptual Art placed greater emphasis on the artist’s intent than the finished piece, challenging conventional art notions and mediums.

Installation view of Motonaga Sadamasa's 'Work (Water),' (1956), "Gutai: Splendid Playground," the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy of the museum.

Installation view of Motonaga Sadamasa's 'Work (Water),' (1956), "Gutai: Splendid Playground," the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Courtesy of the museum.Above all, the influence of Japan’s Gutai Art Association (具体美術協會, 1954–1972), commonly referred to as “Gutai,” cannot be ignored in Korean experimental art. Led by Jirō Yoshihara from 1954 to 1972, the Gutai movement was an avant-garde initiative among Japan’s emerging artists. It aimed to establish international connections and solidify its position overseas, leaving a significant mark on world art. Notably, the Guggenheim Museum held a major Gutai retrospective in 2013.

Gutai also drew influence from Western conceptual art, engaging in gestural painting, performances, and a back-and-forth exploration of materiality. This movement brought about changes in Japanese art discourse, often referred to as the “anti-art movement,” as it focused on the act itself rather than using art as a political gesture.

Researcher Park Misung briefly examined the similarities between Gutai art and Korean experimental art. For instance, during the Young Artists Association Exhibition in Korea in December 1967, participants carried pickets with slogans advocating realistic participation in a protest march, which resembled the 1957 protest march by the Group Kyushu (Q) within the Gutai collective. Additionally, the resemblance between Lee Seung-taek’s 1970 Wind series and Motonaga Sadamasa’s Work (Water) (1956) was also noted.

Lee Seung-taek, ‘Wind-Folk Amusement,’ (1971). Courtesy of Lee Seung-taek, Asian Culture Complex and Gallery Hyundai.

Lee Seung-taek, ‘Wind-Folk Amusement,’ (1971). Courtesy of Lee Seung-taek, Asian Culture Complex and Gallery Hyundai.Though Korean experimental art and Japan’s Gutai art shared similarities, they also diverged in significant ways. While Japan’s Gutai art was primarily aimed at showcasing art itself, Korean experimental art contained a sense of social critique of the Korean art scene and national policies.

The Korean experimental art movement was influenced by various art movements, but it would be a stretch to say that it directly adopted any specific form. The emergence of object art and performance art in the late 1960s and onward in Korea can be seen as instances where diverse art forms were embraced to express a critical awareness of reality.

Research on Korean experimental art remains somewhat limited, and the relationship between Korean experimental art and the global art context has yet to be deeply explored. As studies progress, understanding the international influences on Korean experimental art is vital, as it will illuminate the unique position Korean experimental art occupies on the international art stage

This article will continue next week.

References

- 국립현대미술관(The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, MMCA)

- 구겐하임 재단(The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation)

- 박미성 (2017) 1960년대 한국의 오브제. 행위 미술과 일본 구타이 미술의 관계, 문화교류와 다문화교육(구 문화교류연구), 6:1, 5-20