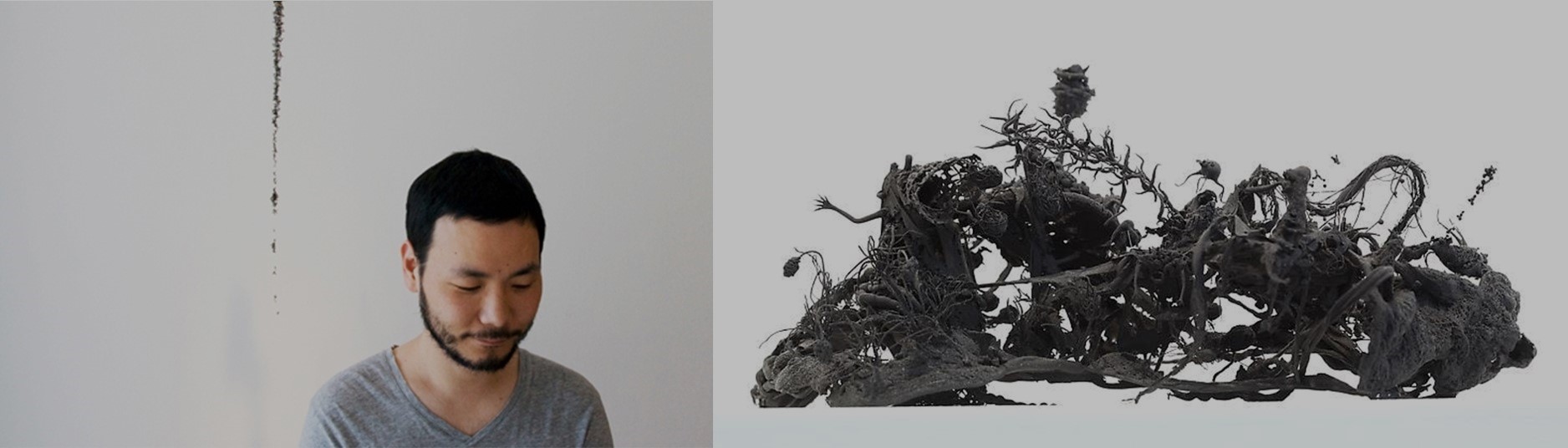

Bahc

Yiso (1957-2004) was one of the most prominent artists who played an important

role in the Korean art scene, working as an artist, curator, and critic from

the 1980s to the early 2000s. Bahc Yiso, whose work since the 1990s has been

characterized by conceptual attitudes and features of contemporary art,

contributed greatly to the formation of the postmodern discourse in the Korean

art world, died at a young age in 2004 after suffering a heart attack.

His

artistic activity can be divided into two periods: 1982, when he studied in the

United States, and 1995, when he returned to Korea. During his time in New

York, Bahc worked under the name 'Mo Bahc' and dealt with issues of identity in

the multicultural society of the United States as a Korean immigrant.

In

addition to his artistic activities, Bahc also founded ‘Minor Injury,’ an

experimental alternative space in Brooklyn, where he was recognized as a young

leader in the New York art scene, representing the voices of marginalized

immigrants and other minorities. After returning to Korea, he worked as ‘Bahc

Yiso,’ creating conceptual art based on a reflective and critical view of

society and reality, while also presenting works that capture a human and warm

view of our lives.

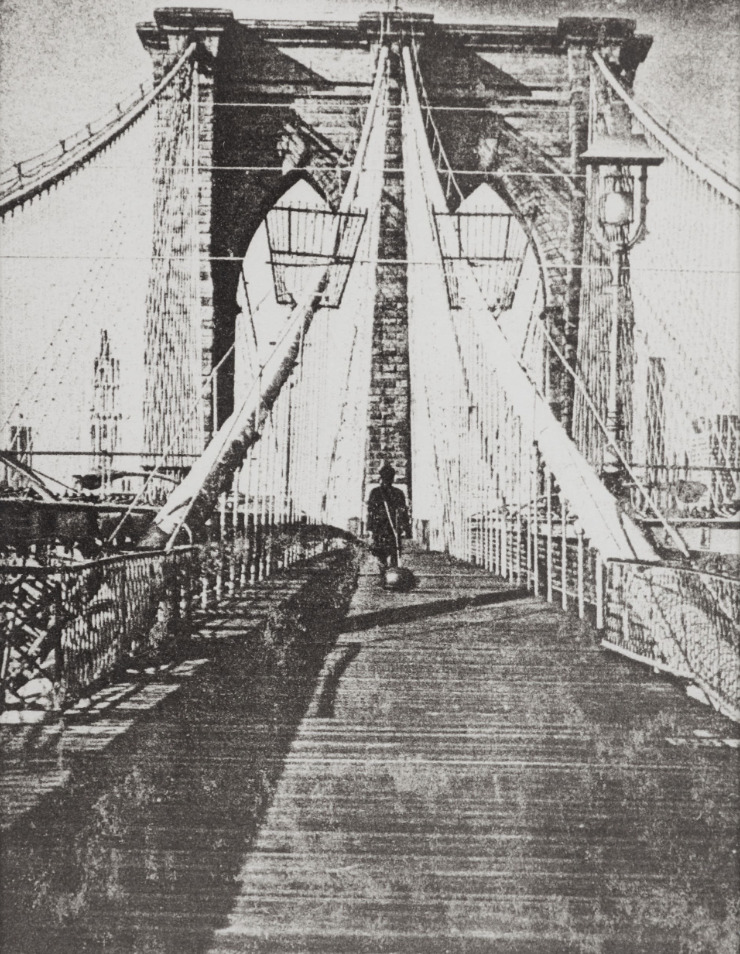

Bahc Yiso, Mo Bahc's Fast After Thanksgiving Day, 1984 ©MMCA

While living in New York City, Bahc created decolonizing works, focusing on narratives of Korean identity as a periphery. At the time, Bahc addressed these themes in his paintings and through performance. On Thanksgiving Day in 1984, Bahc was invited to a dinner hosted by an American family, and for the next three days, he went without food and walked across the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City with a rice cooker tied around his neck with a leash, while his colleague, the artist Kang Ikjoong, photographed him from behind. The artist's act was a gesture of his determination to silently defend his identity as a Korean in the Western art world, as well as an expression of his identity as a political artist.

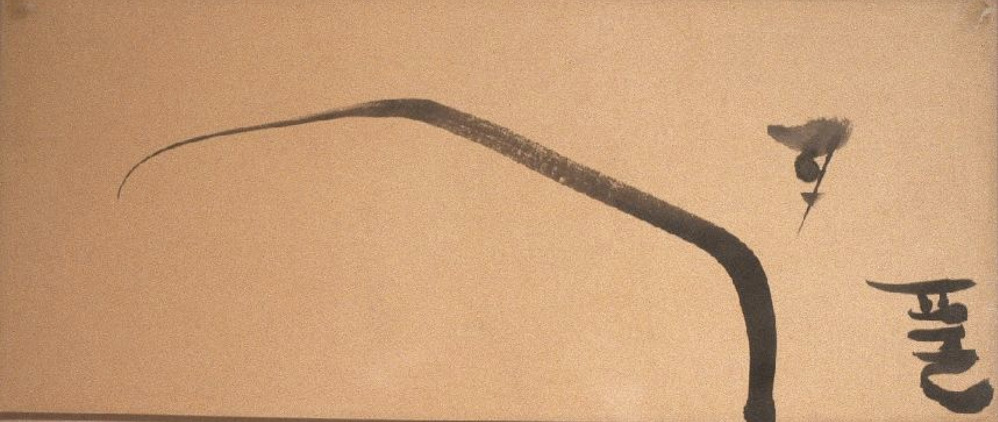

Bahc Yiso, Weed,

1988 ©MMCA

Bahc Yiso, Weed,

1988 ©MMCABahc has repeatedly grappled with his

identity as a Korean immigrant who is categorized and defined as an ethnic

minority within American society. He found the dilemma of being

"Korean" to be something that made him aware of his roots and proud

of them, while also playing an important role in introducing the then-unknown

Korean art to the United States, but also being othered and stereotyped as

"Korean.

Bahc's response to this was to paint simply

weed. He roughly drew an orchid, the subject of traditional literati painting,

and wrote texts such as '풀(weed),' '그냥 풀(simply weed),' and '잡초도

자란다(weeds also grow)' alongside it, and even stamped it in

red. To those familiar with literati painting, the drawing looks sloppy, and to

someone who doesn't know Hangeul, it looks like a typical 'Korean' drawing.

But once knowing the meaning, it makes

them realize that their gaze on the 'simply weed' is a gaze that knows nothing.

In this way, Bahc reveals how the 'traditional' becomes exoticized and othered

in the eyes of Westerners through his sloppy paintings of weed that borrow

traditional materials.

Bahc Yiso, Your Bright Future,

2002 ©MMCA

Bahc Yiso, Your Bright Future,

2002 ©MMCAThe artist continued to work on this

theme of identity, concluding his work on identity with Homo Identropus

in 1994, shortly before his return to Korea. After returning to Korea, his work

gradually shifted from painting to three-dimensional and installation works.

During this period, Bahc's work was characterized by a reflective attitude

toward the universal value of the chaotic, hopeless, and fantastic world.

His signature work, Your Bright

Future (2002), is an installation in which several bright standing lamps

illuminate one corner of a wall. Despite the hopeful title of 'Bright Future',

the composition is unremarkable, with the angular standing lamps only

illuminating the corner. It represents the futility of hope, but the inability

to give up hope altogether. This attitude of looking at small and insignificant

things, such as a small corner, with a fragile but affectionate gaze, and

conveying hope, runs through Bahc's later works.

Bahc Yiso, Venice Biennale,

2003 ©MMCA

Bahc Yiso, Venice Biennale,

2003 ©MMCASelected as the artist for the Korean

Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, Bahc installed a slender, fragile-looking

structure of timber in the front yard of the Korean Pavilion. Venice

Biennale (2003) is an installation consisting of four timbers that make up

a rectangular skeleton, which is set on four basins filled with water.

On the top corner, diagonally across

the top, the 26 international pavilions of the Giardini della Biennale and the

three Arsenale buildings are sculpted in tiny, three-centimeter-sized pieces,

lined up in a row.

The artist questions and satirizes the

authority of the Biennale by shrinking and simplifying the Biennale's national

pavilions, which are a window for the expression of desire and a sign of

cultural hegemony. De-authoritarian and de-monumentalized in size, material,

and method of reproduction, the work is transformed into an innocent and cute

landscape, which, as the artist says, seems to be "a future world where

people live together without competition."

Bahc Yiso, We Are Happy, 2004 ©MMCA

Unpretentious and unadorned, Bahc's

art comes across as honest. Bahc's sincere desire to live a simple life away

from worldly values is reflected in many of his works. For example, Honesty,

a Korean adaptation of Billy Joel's pop song 'Honesty', sung and recorded by

the artist himself, leaves a deep impression in line with his attitude toward

life.

In 2004, while preparing for an

invitation to the Busan Biennale, he suddenly suffered a heart attack and died.

We Are Happy (2004), which became his last work, was a work that applied

the irony of seeing the North Korean propaganda "We Are Happy" on a

building in Pyongyang, North Korea, on television to South Korean society.

The work ironically expresses the

South Korean society that pushes for success and advancement as much as the

North Korean propaganda and invites the question, "Are we really happy?”

The artist wanted to erect a giant sign that simply reads 'We are happy' on the

rooftop of a building or in front of a public square, but due to his untimely

death, it remained a sketch, but was later installed as an actual sign in the

parking lot of the 2004 Busan Biennale exhibition hall by fellow artists.

Bahc Yiso was an artist who constantly

thought about the role of art by looking at the gaps in our society, the

peripheries outside of power, and the trivial and fragile beings with a calm

and sincere attitude. Although he passed away only 10 years after returning to

Korea, his art has influenced subsequent generations of artists, making Korean

contemporary art more diverse and richer.

"I think about what my paintings, my works, can do. What kind of changes can they make when they are hanging on the wall and placed in the museum building? Does art have to be about change? What is that 'change'? How do questions that follow one after another go? I just love my inane jokes. I feel like the world is alive and kicking, and my head is whirling, as long as I'm telling these jokes." (Artist's Note, 2004)

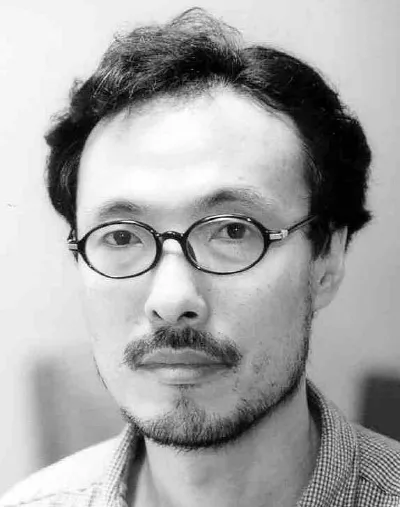

Artist Bahc Yiso ©The Kyunghyang Shinmun

Bahc Yiso founded ‘Minor Injury’ in New York in 1985 and served as its director until 1989. After returning to Korea in 1995, he took up a position a professor at SADI (Samsung Art & Design Institute) which had recently opened. He presented his works in a number of major national and international exhibitions including Gwangju Biennale (1997) and Yokohama Triennale (2001). In 2002, he won the Hermès Korea Missulsang and was participated in the Korean Pavilion at Venice Biennale as a representative artist of Korea. After his death, his retrospective exhibitions were held at Rodin Gallery in 2006; Art Sonje Center in 2011 and 2014; and National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon (2018).

References

- 월간미술, 박이소: 기록과 기억 :

- 국립현대미술관, 박이소: 기록과 기억 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Bahc Yiso: Memos and Memories) :

- 부산비엔날레 2024, 박이소 (Busan Biennale 2024, Bahc Yiso) :

- 경향신문, 추수감사절 이후 박모의 단식, 2018.09.21 :

- 아트인사이트, [Project 당신] 박이소, 20년의 기억, 2020.09.13 :

- 국립현대미술관, 박이소 | 당신의 밝은 미래 | 2002 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, BAHC Yiso | Your Bright Future | 2002) :

- 뉴스핌, 국립현대미술관 서울관, 박이소 작품 '우리는 행복해요' 전시 보류, 2018.07.31 :

- 국립현대미술관, 박이소 | 베니스 비엔날레 | 2003 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, BAHC Yiso | Venice Biennale | 2003) :