Choi

Jeong Hwa (b. 1961) has created a variety of installations that bring cheap

everyday consumables such as plastic baskets, piggy banks, artificial flowers,

and brooms into the realm of art. By transforming these mass-produced everyday

consumer goods into artworks and moving them into museums, the artist blurs the

boundaries between high art and popular culture through so-called cheap pop

culture, or kitsch, and captures a slice of Korean society.

Choi

participated in a ‘museum’ group formed in 1987 around Koh Nak Beom and Lee

Bul, criticizing the tradition and authority of museums and breaking away from

the pre-existing art world, and attracted attention as a heretic in the art

world. Since the mid-1990s, he has been active in various fields as an interior

designer, installation artist, and art director, expanding the horizons of

Korean contemporary art and garnering attention as an artist who captures the

locality and universality on the international stage.

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Rotten Art, 1995 ©Choi Jeong Hwa

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Rotten Art, 1995 ©Choi Jeong HwaChoi's early works were characterized

by a consciousness of criticizing the existing system of the art world. Among

them, Rotten Art, which was exhibited in 1995, displayed photographs of

meat, vegetables, and fish that had been decaying for a while in ornate gold

frames alongside photographs of unspoiled items. By placing photos of rotting

food in overly ornate frames, rather than the image of high art, the exhibition

blurs the boundaries of what constitutes art, while also criticizing and

satirizing the authoritarian and conventional art world of the time.

In addition, the artist brought an

installation work made of whole pig heads found in the market into the

exhibition hall, or showed works that used common and cheap objects in our

daily lives rather than conventional art materials.

최정화, 〈플라스틱 파라다이스〉, 1997. 파리 OZ 갤러리 설치 전경. ©최정화

최정화, 〈플라스틱 파라다이스〉, 1997. 파리 OZ 갤러리 설치 전경. ©최정화Plastic is one of the cheap,

ready-made products that appears as a material in Choi's work. Plastic is also

a material that epitomizes the cultural characteristics of consumer society in

that any object can be made cheaply by mimicking its appearance while ignoring

the properties of the existing material. Focusing on the cheap, lightweight,

colorful, and transformable practical properties of plastic, the artist shows

various variations of plastic baskets, such as stacking them in the form of a

tower or transforming them into lights.

Among these works using plastic as a

material, Plastic Paradise (1997) is the work that put Choi on the world

stage. Plastic Paradise is an installation in the form of a tower

stacked with cheap plastic colanders in a lime green color that can be

purchased cheaply in the Korean traditional market.

Unlike the materials

alone, the way they are stacked vertically and dominate the exhibition space,

they appear to be beautiful works of art that make us forget for a moment that

they were originally cheap objects. With a simple stacking motion, the artist

transforms familiar everyday objects into works of art and creates temporary

structures that can be easily dismantled, playfully parodying the desire for verticality

and permanence

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Breathing Flower, 2010, Installation view at Biennale of Sydney ©Choi Jeong Hwa

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Breathing Flower, 2010, Installation view at Biennale of Sydney ©Choi Jeong HwaIn 1995, Choi presented a giant potted

flower sculpture made using blower hydraulics and fabric outside the National

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), using the flower images he had

been collecting since the early 1990s as the sole object. Since then, Choi has

continued to work on giant floral balloons made by inflating fabric, which have

been exhibited at various biennials and leading institutions around the world.

In the Breathing Flower series,

Choi added the motion of folding and unfolding flowers by installing motors.

The repetitive movement of the mechanical flowers, which are made of artificial

materials that do not decay, paradoxically reveals the finitude and emptiness

of living beings. Rather than stone or metal, which are commonly used in public

art, the balloon sculptures, which are nothing more than pieces of fabric when

deflated, are installed around the world, deconstructing the conventions of art

and blurring the boundaries between art and non-art.

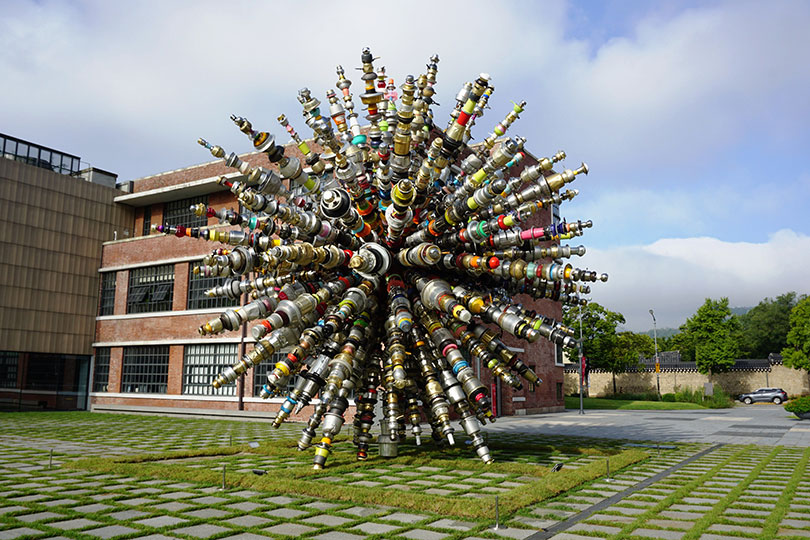

Choi Jeong Hwa, Dandelion, 2018. ©MMCA

Furthermore, Choi's public art works

have been presented in the United Kingdom, Belgium, the United States,

Shanghai, and elsewhere as part of the Happy Together series, a

participatory project created with citizens. This is a public art project in

which visitors bring their own plastic waste to the museum, and unlike artworks

in museums, which are usually untouchable, they are created and installed in a

way that breaks down the boundaries between the artwork and the audience, such

as children kicking and playing with colanders that are parts of the artwork.

Such participatory art projects have

also been carried out in Korea since 2008 under the name ‘Gather Together.’ In

2018, as part of the MMCA Hyundai series, people collected tableware that they

no longer used.

The collected utensils are then

engraved with the names of the donors and turned into artworks. About 7,000 of

the donated household items were transformed into a large-scale installation, Dandelion

(2018), which was installed outside the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Seoul in the form of a giant dandelion seed, 9 meters tall

and weighing 9.8 tons.

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Blooming Matrix, 2016-2018. ©MMCA

Choi Jeong

Hwa, Blooming Matrix, 2016-2018. ©MMCASelected for the Hyundai Motor Series

at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 2018, Choi's

exhibition “MMCA

Hyundai Motor Series 2018: CHOIJEONGHWA - Blooming Matrix” shows the materiality of

objects that extends beyond plastic, which has been considered his signature

material, to wood, steel, and fabric. Among them, Blooming Matrix (2018) is an installation work in which objects

collected by the artist from various places are harmonized together, allowing

the audiences to pass through and appreciate the works in which the time and

space of the objects are mixed.

As in his previous work, Plastic

Paradise, 146 flower pagodas made of stacked objects were gathered to

create a serene forest-like space. In this exhibition, the artist also

presented the traces of time that are embedded in old and worn-out household

items, such as a tower of old dining tables made of donated furniture from a

house where three generations have lived, and old washboards collected from

different parts of China, arranged in a regular pattern across the walls.

In this way, Choi's work communicates

with the audience in an easy way and form. Choi starts from our daily lives and

reinterprets the beauty he finds in them in the form of art, allowing audiences

to enjoy them together.

“Art is not to be possessed, but to be enjoyed. A work of art is not to create beauty, but to find beauty in a small leaf that falls in front of your house.”

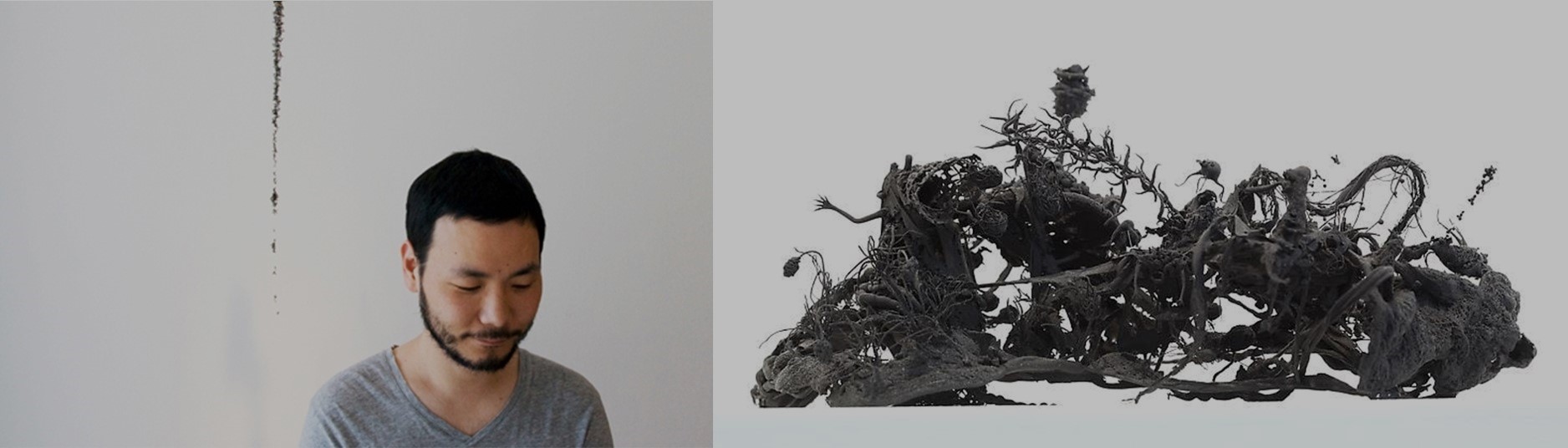

Artist Choi Jeong

Hwa ©Choi Jeong Hwa

Artist Choi Jeong

Hwa ©Choi Jeong HwaBorn in Seoul in 1961, Choi Jeong Hwa studied painting at Hongik University. Choi has participated in various exhibitions such as “When Forms Come Alive” (Hayward Gallery, London, 2024), “Come Together” (Education City, Qatar, 2022), “SARORISARORIRATTA” (Gyeongnam Art Museum, P21, Changwon, Seoul, 2020), “MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2018: CHOIJEONGHWA - Blooming Matrix” (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2018), Honolulu Biennale (2017), “Megacities Asia” (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2016), Busan Biennale (2014), 17th Sydney Biennale (2010), Gwangju Biennale (2006), Venice Biennale - Korea Pavilion (2005), Liverpool Biennale (2004), Lyon Biennale (2003), and many other exhibitions, biennales, and projects.

References

- 최정화, Choi Jeong Hwa (Artist Website)

- 국립현대미술관, MMCA 현대차 시리즈 2018: 최정화 – 꽃,숲 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2018: CHOIJEONGHWA - Blooming Matrix) :

- 코리안 아티스트 프로젝트, 최정화 (Korean Artist Project, Choi Jeong Hwa)

- 국립현대미술관, 야외프로젝트 «최정화: 민들레» (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, Outdoor Project CHOIJEONGHWA: Dandelion

- 메종코리아, 최정화 작가의 향유하는 예술, 2022.11.04 :