The

Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art has consistently hosted its Wooyang Artist

Series as a means of empowering established artist in the Korean art community

to further advance (and, at times, completely change) their work. The 2018

Wooyang Artist Series features Meekyoun Shin, who has created an artistic world

based on a soap motif.

Having engaged in creative activity for over 25 years

while moving back and forth between London and Seoul, Shin is taking the

opportunity this exhibition provides to highlight her past work, feature 62 new

creations and artworks not yet unveiled in Korea, and introduce an

architectural project that was originally featured at 《The Abyss of Time: Meekyoung Shin》 (solo

exhibition at Arko Art Center). This large-scale exhibition of 230 artworks by

Shin is featured especially for the residents of Gyeongju.

The

subtitle of the exhibition (《Meekyoung Shin

– Ancient Future》) was borrowed from an essay of the

same title by linguist Helena Norberg-Hodge. Also, the exhibition was inspired

by Shin’s unique perspective on identifying contemporaneity between the current

era and the distant past by dismantling the standardized perceptions of ancient

civilizations and cultures. This exhibition aims to reassert this

inter-temporal continuity for today’s viewers.

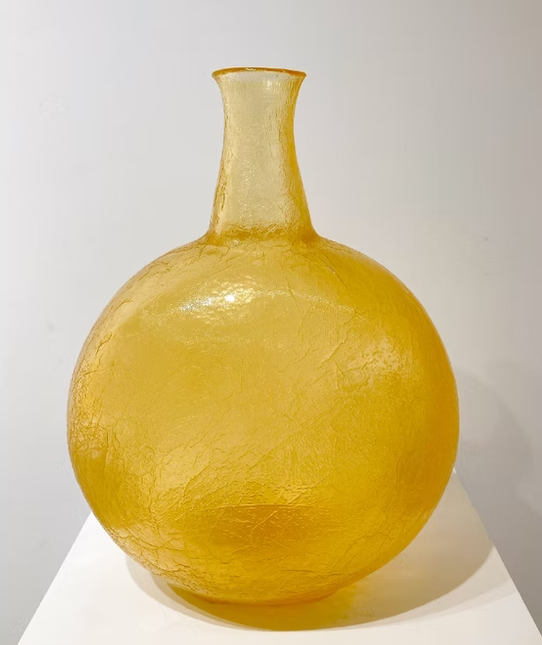

Shin

uses soap, a common everyday item, to create Western sculptures and “painting,”

Buddha statues and Asian-inspired ceramic ware, and other objects that are

representative of certain cultures, such as the ruins of famous buildings.

These works are not merely re-creations of actual things, but represent the

intentional de-contextualization of an object’s external identity as well as

the birth of a new entity through the transference of the subject’s original

context to a different “original copy.”

They are visualization of concepts that

can only be portrayed through the physical weakness of soap (questioning of

firmly established authority and hierarchies based on an awareness of

modernization’s Western bias, inevitable distortion of traditional and interpretation

caused by different cultural backgrounds, contemplation of the validity/establishment

of artwork or artifacts, irony of time being increasingly well visualized

through the deterioration and disappearance or remains, etc.).

This

exhibition focuses on the phenomenon of Shin’s artworks being interpreted

differently depending on the venue in which they are exhibited and cultural

backgrounds of the viewers as part of the artwork. This feature of Shin’s work

will heavily overlap with the spatial characteristics of Gyeongju, which is

known as an “outdoor museum” for its high concentration of historical artifacts

and relics, accentuating the chaos and confusion between the original and the

replica. The exhibition makes it easy for visitors to see the ruminations on

fundamental questions on human existence that lie behind the elaborate façade

of well-known works of art.

When visitors encounter Shin’s artworks at the art

museum, after having already seen many famous artifacts excavated from Korean

royal tombs, including the Gilt-bronze Seated Amitabha Buddha of Bulguksa

Temple, Bonjonbul (principal Buddha statue) of Seokguram Grotto, Gameunsa

Temple Site, and Hwangnyongsa Temple Site, they can interpret the artworks on

an entirely new level by discovering yet another identity. Such creation of new

identities is achieved by taking on a museum- style format as “exhibits”

(painting, building, Buddha statue, pottery, Greek sculpture, etc.) of an

official “exhibition.”

The

large-scale architecture project Ruinscape, which is set up

inside the exhibit hall, adds two tons of soap to existing items to create a

scene of sublime beauty. The ruins have the same effect as a screen,1 in that

they depict human mortality. The past glints past vanished remnants (like a

time lapse), while the view of aged and broken remains has the effect of

creating an overwhelming nostalgia, reminding us of the temporality of

existence. The ruins visualize something that has already disappeared.

Ironically, however, such visualization simultaneously emphasizes the eternity

of its reinterpretation/rebirth. An observatory-style stairway allows visitors

to have an aerial view of the ruins.

Positioned

separately from the section displaying Shin’s series artworks is a large

pedestal in the format of a triptych (picture/relief carving done on three

panels) from the Middle ages, on top of which are over 30 Buddha statues made

from soap from various projects. The grouping together of identical formats

serves to highlight the content of Shin’s works.

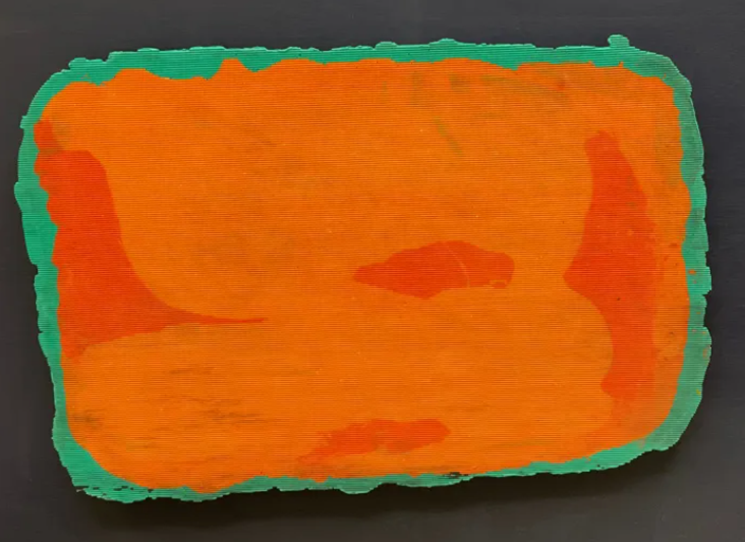

This

exhibition will also feature the ‘Painting’ series, which deconstructs the

meaning of the painting; the ‘Translation: White porcelain’ series, which is

comprised of new is comprised of new artworks and works that have not yet been

presented in Korea; a large standing Greek statue that is part of the

Weathering Project; a Buddha statue from the Toilet Project; and the ‘A Petrified

Time’ series, which condense and corrodes the ceramicware featured in the

Translation series in order to show the passage of time.

In

addition, the act of “weathering” the statues displayed for the Weathering

Project outside the Arko Art Center by placing them at the entrance

and on the rooftop of the center enables visitors to witness the “overlapping”

of the passage of time as they from one space to another while viewing the

exhibition. The Toilet Project, which offers everyday

experiences of artwork, will be installed inside the museum’s restrooms,

thereby adding another dimension to the museum’s indoor and outdoor exhibition

spaces. Both projects question the practice of turning objects into works of

art through hierarchical separation dome with white cubes, presenting the

effects of the passage time on the artwork’s external features as the work of a

“second artist” or the viewer’s actions rather than focusing on the artwork

itself as a complete entity.

Meekyoung

Shin’s future creations are expected to be even broader in scope in terms of

both their internal and external aspects (East-West, sculpture-architecture,

extinction-eternity, etc.).

1

Jookis Min, “Aesthetic Experience of Ruins: Memory of the Place without Story,”

The Korean Journal of Aesthetics, Vol.81, No.1, March 2015, pp. 197.