Exhibitions

《All the Past Comes to the Present》, 2023.11.17 – 2023.12.24, HITE Collection

November 17, 2023

HITE Collection

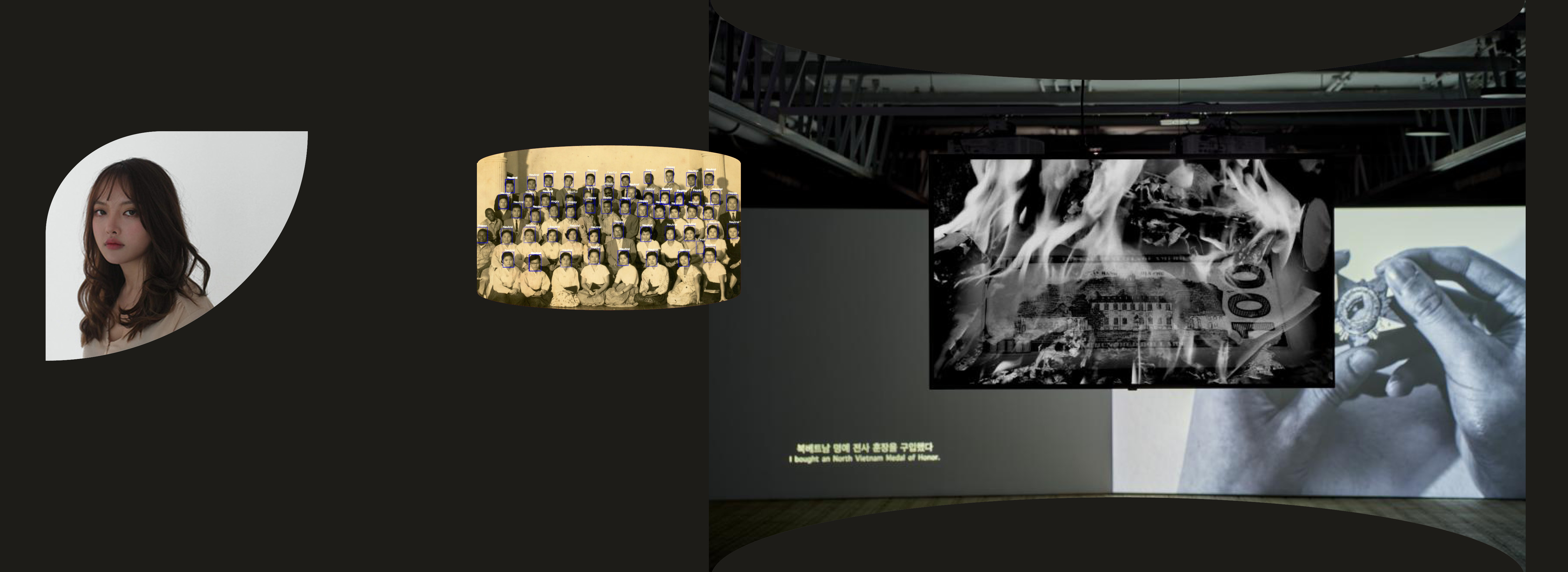

Installation view of 《All

the Past Comes to the Present》 © HITE

Collection

As part of

its annual Young Artists Exhibition series, held since 2014, HITE Collection

presents 《All the Past Comes to the

Present》. This year’s exhibition focuses on the ways in

which a younger generation—moving at the speed of light—engages sensorially

with video, introducing the works of four artists, Kwak Sojin, Kwon Heesoo, Min

Hyein, and Yeoreum Jeong, all of whom take experimental approaches to video and

moving images.

Some of

these artists are interested in the operational principles and mechanisms of

cameras and other recording devices, exploring the relationship between how

optical machines capture images and how human visual perception functions.

Others reference the genre conventions of cinema as well as the experiments of

avant-garde filmmakers. Like certain performance video artists of the 1970s,

they sometimes treat video and moving images as sculptures that move constantly

through space, or as subjects of physical experimentation, presenting optical

experiments that verge on magic.

At times, they draw on the provocative

audiovisual experiences readily encountered in everyday life today—such as

black-box footage, CCTV recordings, YouTube videos, and memes—as source

material. They also address memories and histories tied to specific places,

borrowing recollections embedded in photographs and archival materials and

weaving them into dense narratives. Although the interests of these four

artists may appear to overlap at first glance, a closer look at the exhibited

works reveals clearly distinct concerns and methodologies for each.

Installation view of 《All

the Past Comes to the Present》 © HITE

Collection

Installation view of 《All

the Past Comes to the Present》 © HITE

Collection

While

preparing the exhibition with the four artists, the author found their

reactions to the HITE Collection exhibition space particularly intriguing. Each

time the artists visited, they expressed admiration for the scenes constantly

generated by the interplay of Seo Do-ho’s Cause and Effect,

the building’s glass walls, and the light reflected off the interior glass

railings at the center of the space. The silhouettes of visitors entering and

exiting the building, as well as cars racing along Yeongdong-daero, often

appeared as incidental performers within these scenes.

Though these sights were

familiar to the author, observing the artists’ responses prompted a renewed

realization: every moment, this exhibition space has already existed as video

or moving images created by the convergence of light, space, and environment.

In other words, light itself can be understood as video.

This line

of thought brought to mind Patricio Guzmán’s film Nostalgia for

the Light(2010), in which astronomers working at an observatory in

Chile’s Atacama Desert and women searching for fragments of bones in the desert

emerge as central figures. The astronomers, who spend their lives observing

starlight, explain that the light we see originates in the distant past.

Meanwhile, women who have spent decades digging through the vast desert with

small shovels in search of the remains of family members lost to Chile’s

military dictatorship resent the seemingly endless landscape.

The stars sought

by astronomers and the bones sought by victims’ families share a common mineral

component: calcium. Calcium is deeply connected to the origins of the universe,

as most calcium in the cosmos was formed through the immense energy released by

supernova explosions. Not only calcium but many of the elements that constitute

our bodies are closely related to the life cycles of stars. This is why Carl

Sagan famously stated that we are made of star-stuff.

The author considers

starlight to be the oldest video or moving image. While connecting celestial

bodies with images is not new—Nam June Paik once remarked that “the moon is the

oldest television”—starlight remains particularly fascinating as an infinite

moving image that has been traveling from the distant past to the eternal

present. Approaching video and moving images through contemplation of light may

seem romantic, but it is also an extremely practical matter.

In this exhibition

space, Trinitron TVs, 4K LED TVs, interval searchlights, and beam projectors

rated at 350, 6000, and 7000 ANSI lumens coexist. Decades of human achievement

in optical technology are gathered here. Even these devices alone demonstrate

that video and moving images are inseparable from optics, and that optics can be understood as the modern and contemporary history of video

itself.

Installation view of 《All

the Past Comes to the Present》 © HITE

Collection

Meanwhile,

within exhibition contexts, video and moving images are generally treated as

immaterial entities that cannot be insured, as long as they exist as

reproducible data files. Art history, too, has often approached video and

moving images as immaterial. Do video and moving images truly have neither mass

nor volume? (Though unprovable, the author personally believes that data, too,

possesses physical mass.)

From the standpoint of realizing an exhibition,

however, video and moving images are intensely material and difficult objects:

they occupy exhibition space and generate countless points of friction and

variables through the devices and programs required for their presentation.

Above all, just as we are made of stellar material, video and moving images

likewise originate in starlight and thus constitute matter of the universe.