While

photography remains Joo Yongseong’s primary medium, the way he employs it has

gradually expanded. In 《Lamentation》, photographs are not presented as isolated images but are combined

with structures in an installation format, spatially articulating how memory is

fragmented, arranged, and systematized through institutional logic. In this

context, photography functions less as evidence of events and more as a device

that exposes how scenes of mourning are staged.

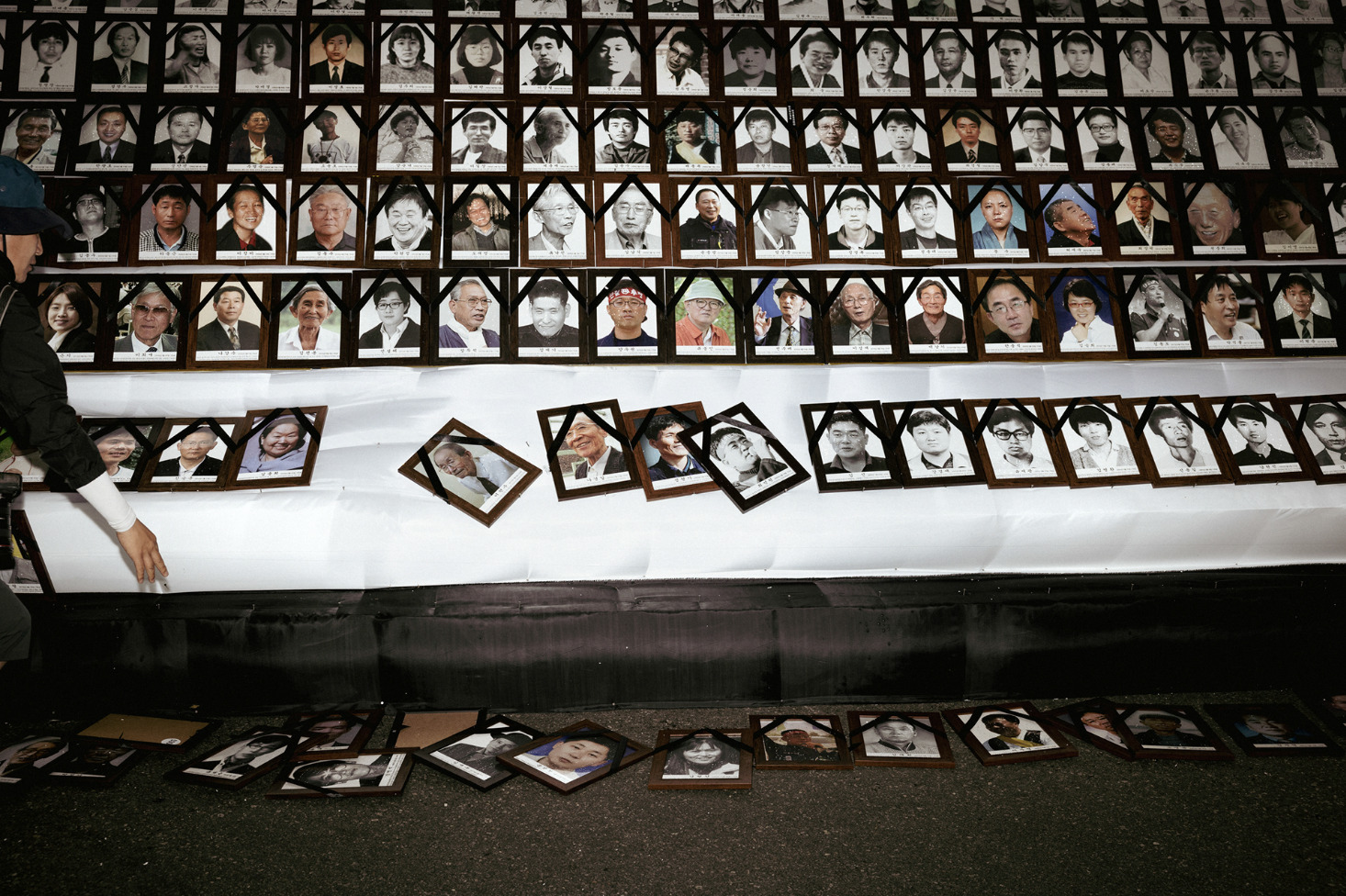

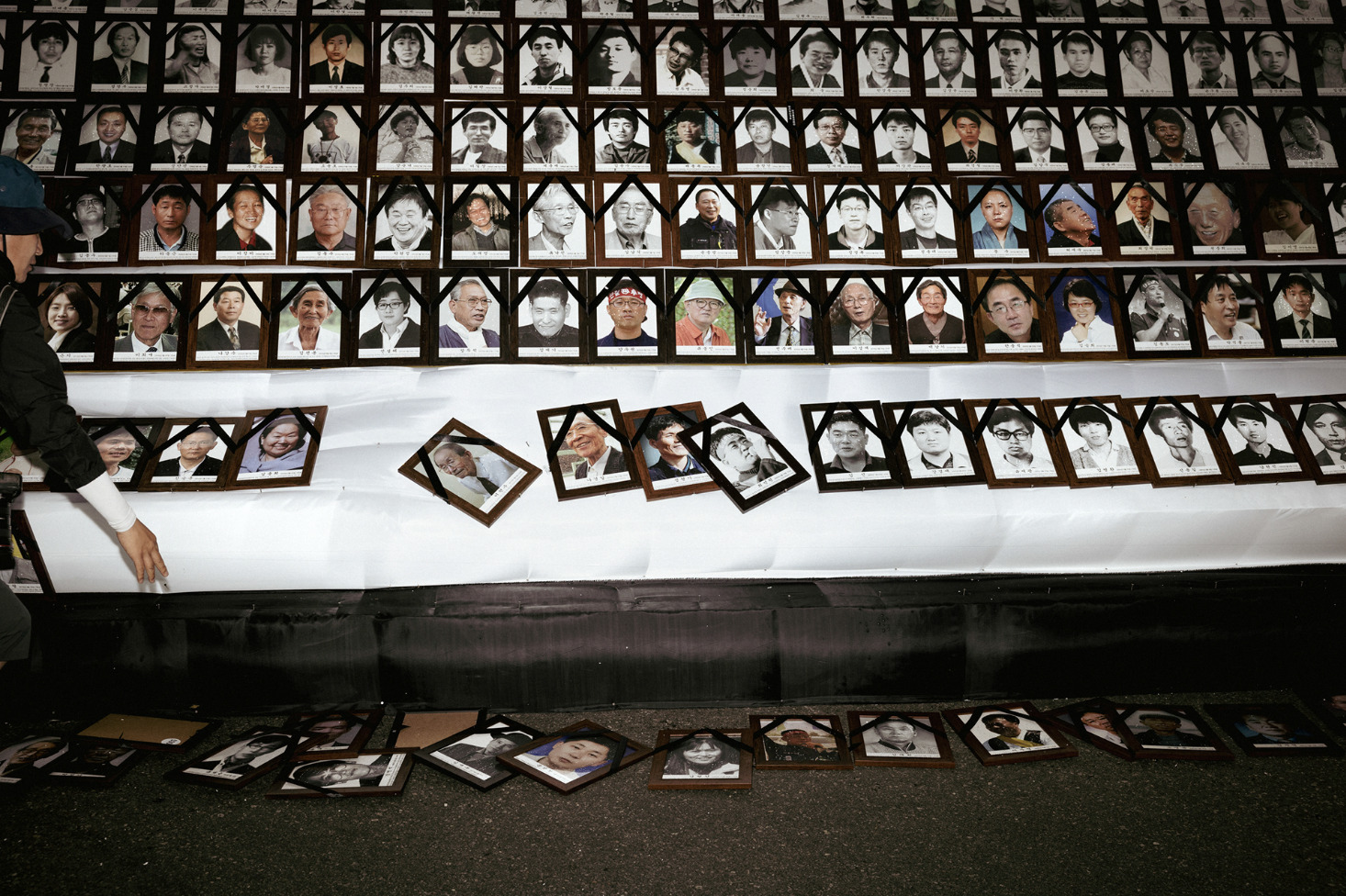

Works from

this period were photographed at monumental sites associated with death,

including excavation sites of civilian massacre victims from the Korean War,

Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, and the Enemy Soldiers’ Cemetery in Paju. Pieces such

as Government Joint Funeral and Memorial Service for the Sewol

Ferry Victims, Ansan, South Korea(2018) and Memorial

Ceremony for National Democratic Martyrs and Victims, Seoul, South

Korea(2018) capture, in an almost raw manner, how the “moment” of

mourning is highly formalized.

In 《The Day After We Are Gone》, portrait

photography comes to the forefront. Works such as Boknam Kim,

Pyeongtaek, South Korea(2021), Eunja Jo, Pyeongtaek,

South Korea(2021), and Young-rye Park, Pyeongtaek,

South Korea(2021) confront viewers directly with individuals embedded

in specific historical contexts. Here, photography operates not as an

instrument of accusation or documentation, but as a channel through which lives

that could not previously speak are allowed to articulate themselves.

In the

‘Red Seeds’ series, places and objects—human remains and personal

belongings—become central visual elements. Excavated bones, hairpins, glass

beads, and shell casings function simultaneously as traces of individual bodies

and as material evidence of collective violence. By recording these elements

with restraint rather than emotional emphasis, Joo positions photography as a

material record that anchors memory in the present, rather than as a

reenactment of the event itself.