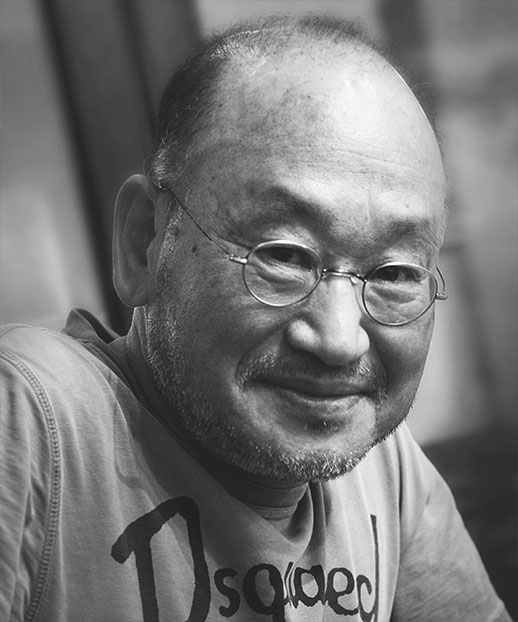

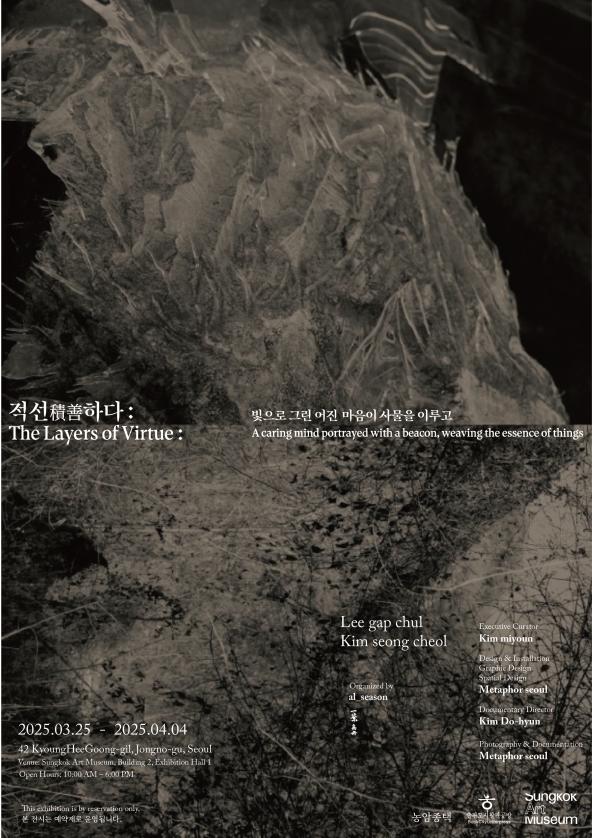

Lee

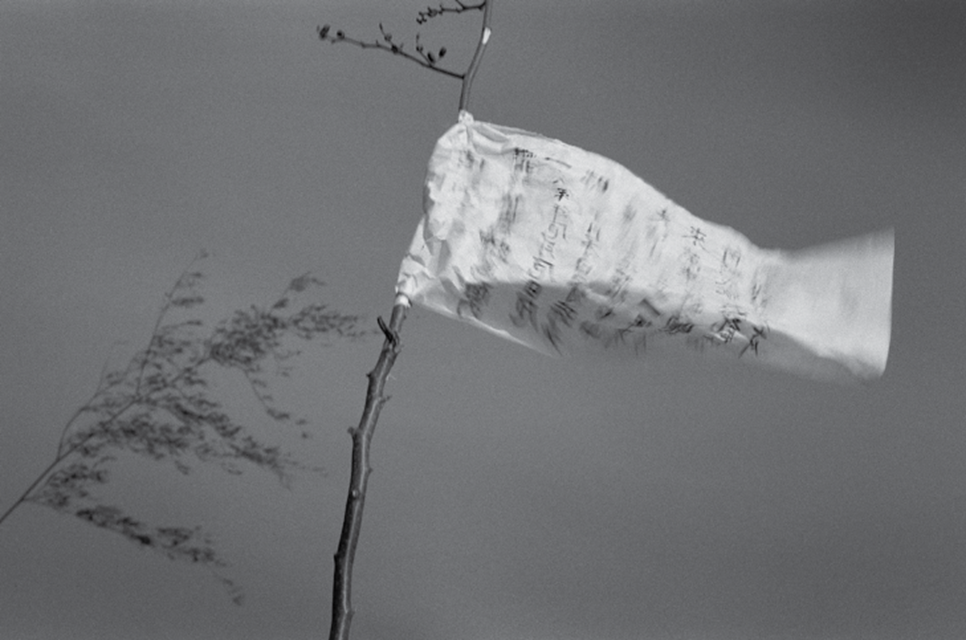

Gapchul’s works are formidable. His images are intense. They demonstrate the

immense power of photography. What is the power in a photograph. First of all,

its arresting images render it difficult for the viewer to look away: the

objects themselves are captivating. Secondly, that which is not shown in the

picture tugs at the viewer in an eerie way. It is rather impossible to identify

what it is, but they emit a strange and mysterious energy.

It is difficult to

distinguish whether this energy comes from the objects or from the pervasive

force of their steep structures and black-and-white tones. What is certain,

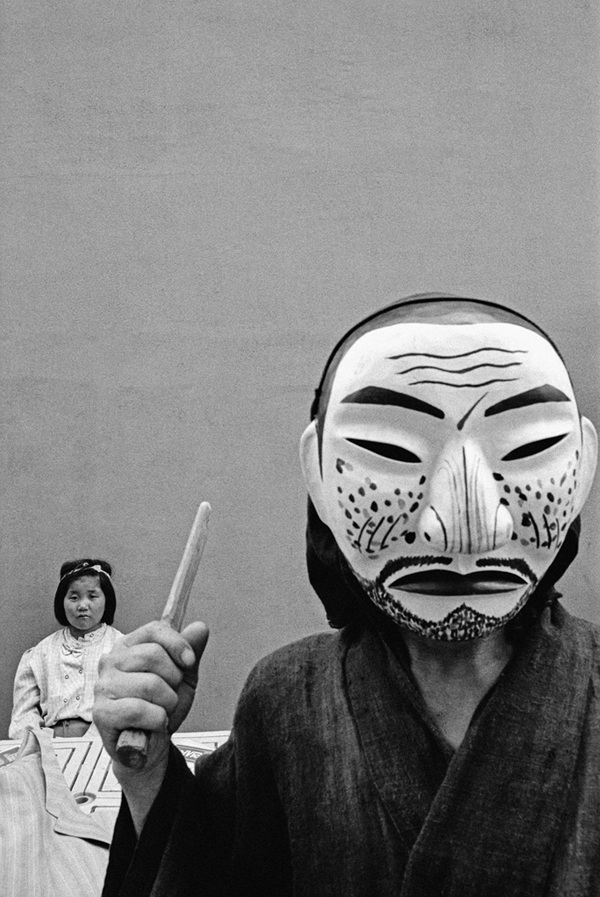

however, is that they emanate a spiritual energy amplified by the mystique and

unique sentiments that are part of the underlying culture of Korea. Therefore,

a cultural or spiritual grasp of Korean folkways and tradition is a

prerequisite in order to detect this energy and spirit. While Lee’s works are

sufficiently attractive as universal visual images, their appeal is magnified

for those who enjoy at least a basic understanding of the history and intimate

sentiments of Korean popular culture.

Like

a shaman feverishly performing a ritual with bells or sacred wooden stick in

her hands, Lee approaches the spirits of this land with a camera in hand.

Without even realizing it, he snaps away like a possessed mediator and, using

his camera as his means, causes the viewer to experience intensely the grief

rooted in the lives of our ancestors. Like a dancing shaman excising the

bitterness from people’s lives with her sword, Lee whirls about, slicing up the

world with his camera.

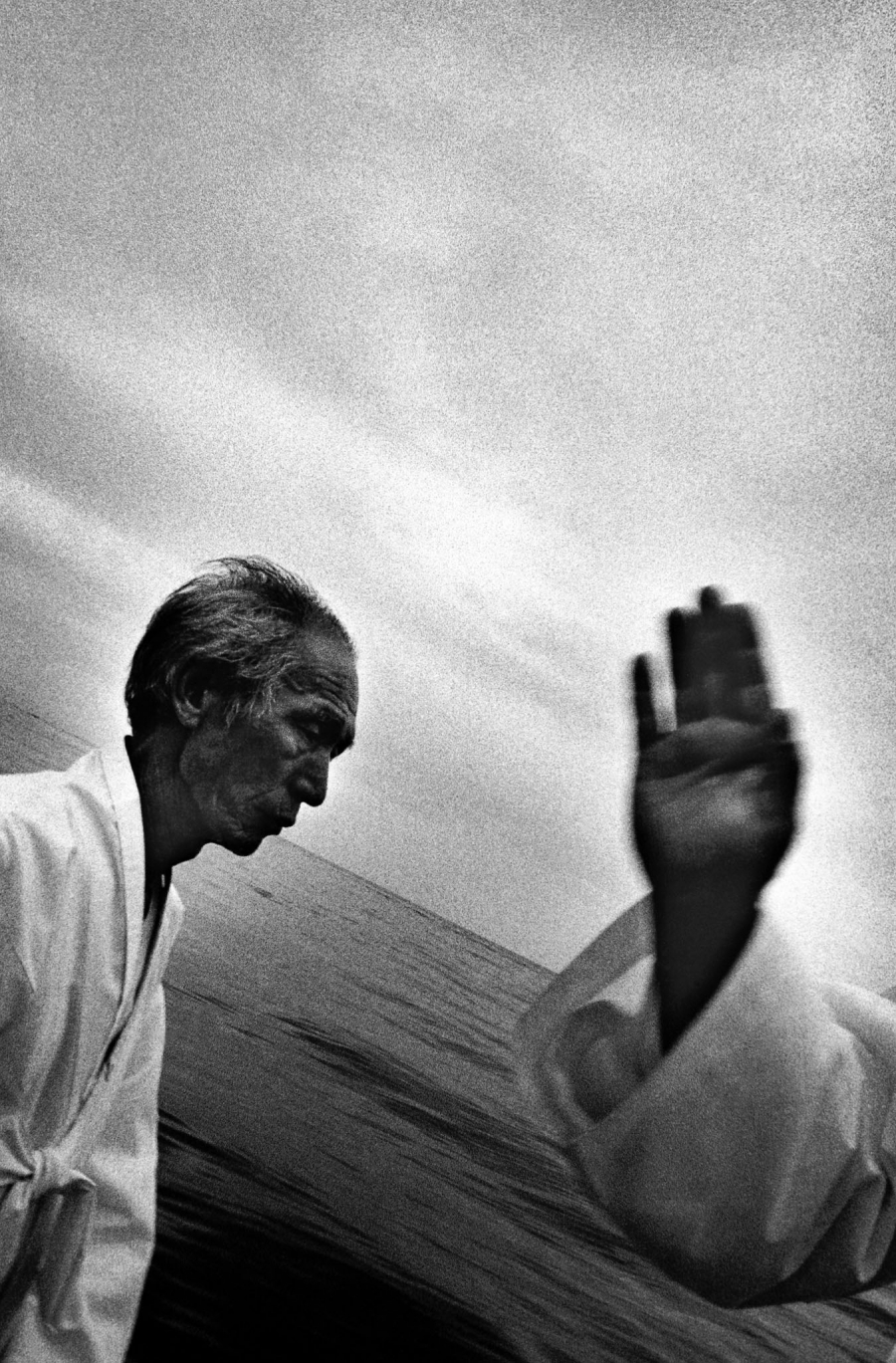

The straight lines he diagonally carves out arouse

delight and a dynamic urge; the angles in the close-up shots captured with a

wide angle lens are surprisingly uninhibited, creating a complete harmony

between the people and the landscape in the photographs. Most important, his photography

and its spiritual depth touch the innermost regions of my subconscious. It

penetrates the mass of the subconscious that constitutes me: the triple layers

of Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist beliefs situated beneath the thin membrane of

modern rationality and, below them all, an intimate layer of shamanism. For

this reason, Lee’s photography is not simply an aesthetic creation, but a form

of enchantment that allows me to come into contact with the protoplasm of my

spirit.

His

works hold a certain power that instantly overwhelms the viewer’s initial gaze.

As a Korean, I feel that his images touch the deepest part of my subconscious

with their spiritual depth. They are filled with a dense energy that has

sustained the lives of Koreans and the multiple strata composing Korean

culture: the Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist thoughts that cannot be effaced by

forces of modernization or globalization, combined with equally persistent

Shamanist beliefs.

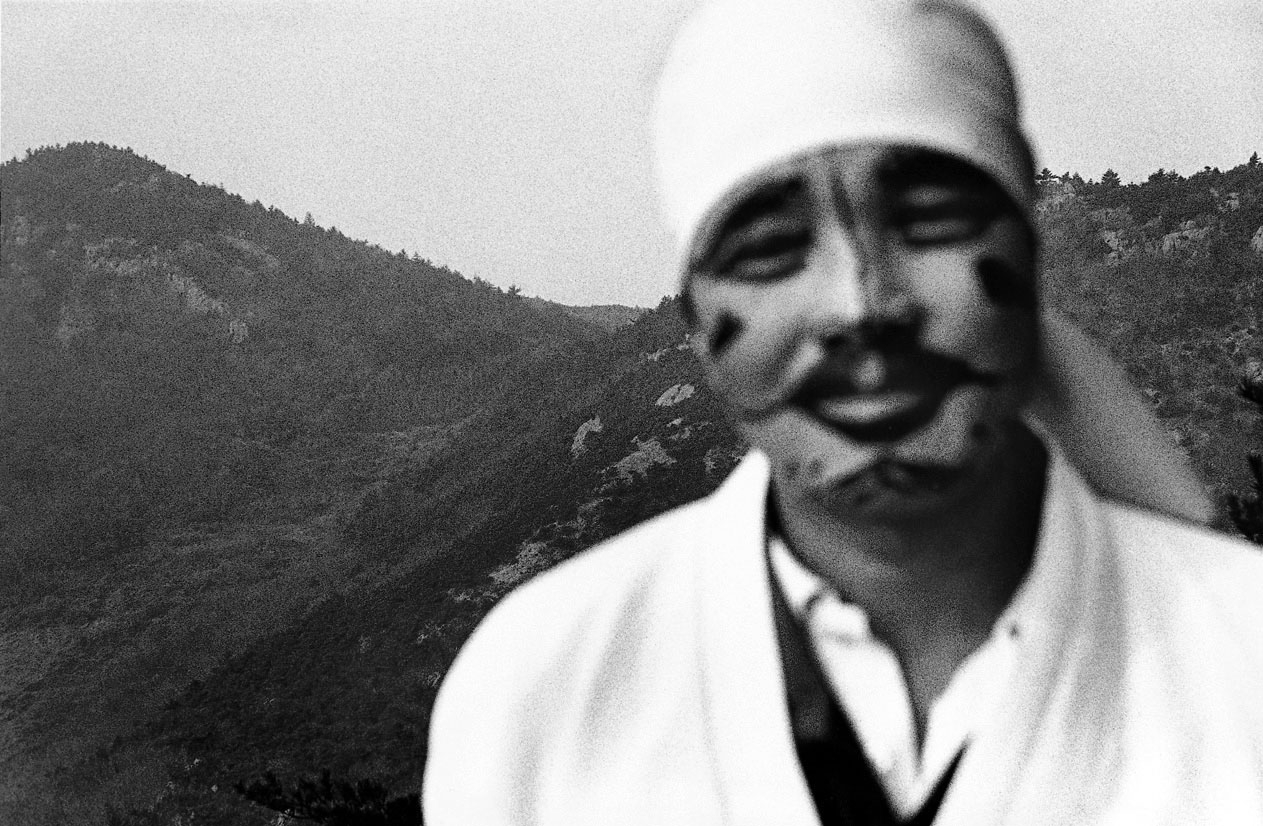

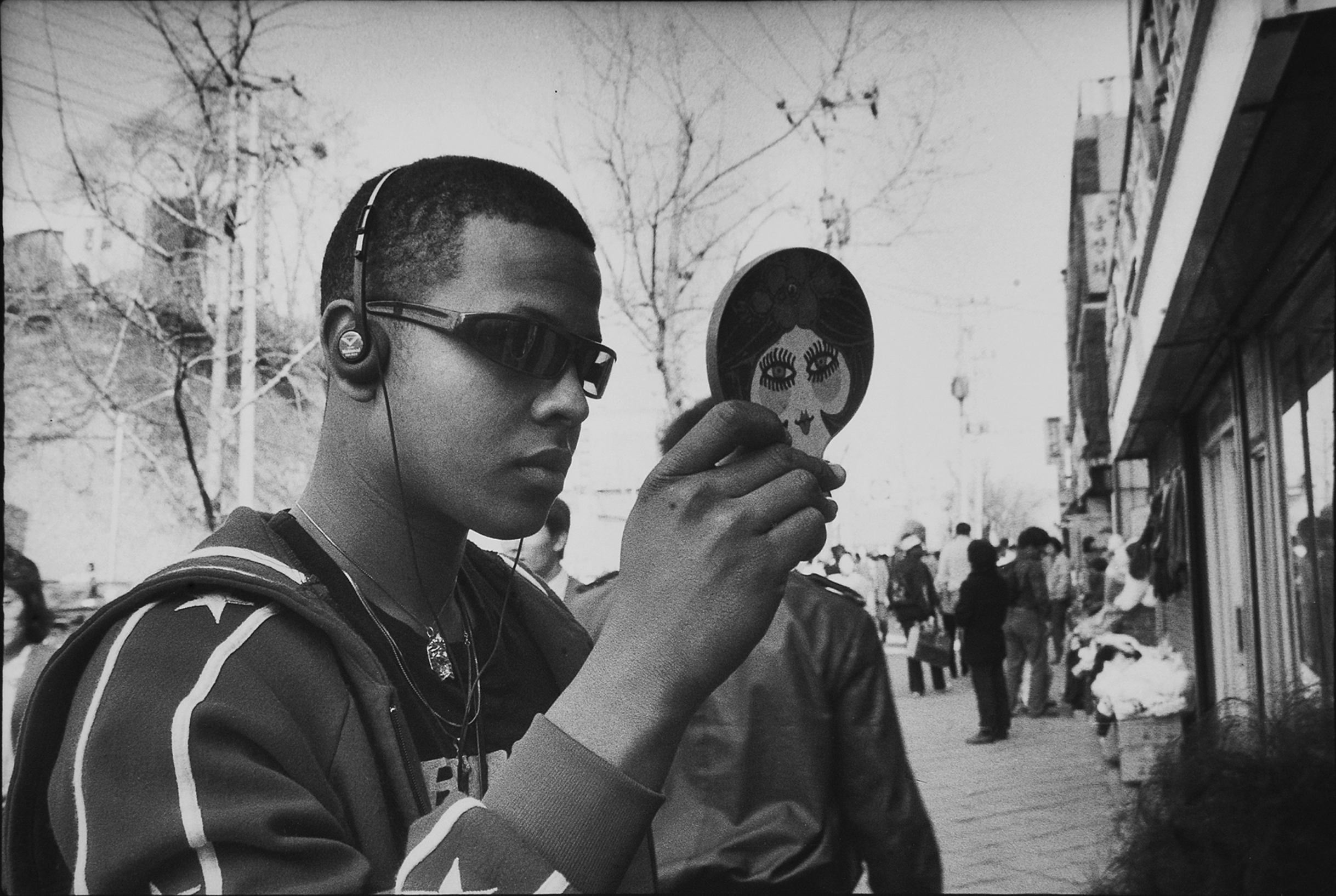

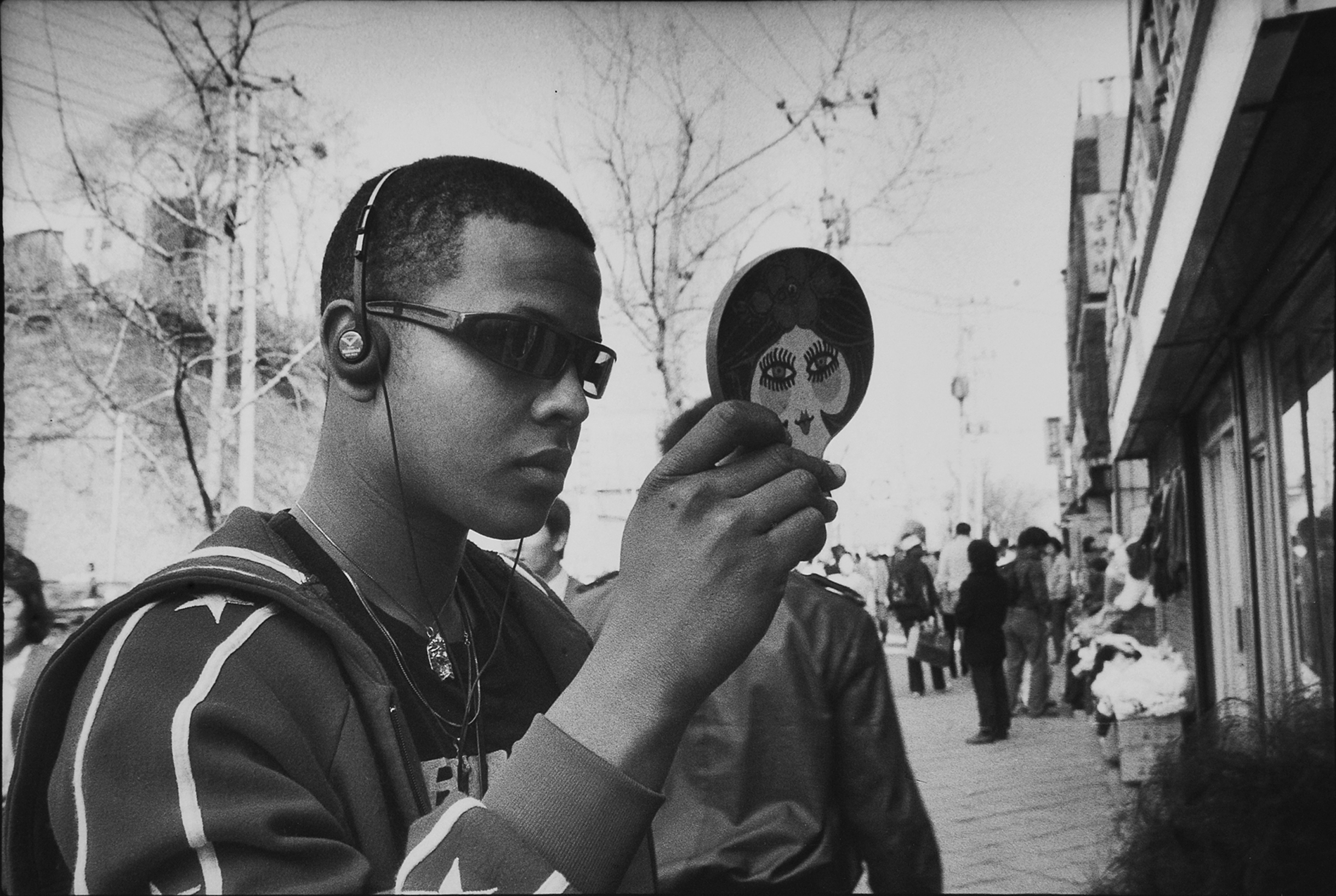

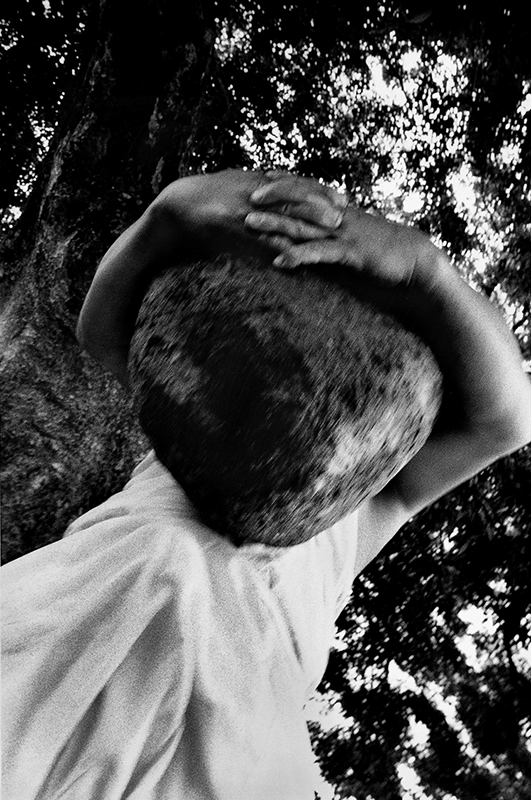

What’s more, Lee’s photographic grammar adopts, more than

anything else, a rather radical framing. The composition is anything but

stable: it is precarious, abrupt and chaotic. Human figures are never presented

as a whole but as absurd parts, for example, a head bursting up in the frame.

The effect is unnerving, even frightening. Because they display shards and

pieces of objects and the world, it becomes difficult to view them with ease.

Instead of serving as a passive object of contemplation, they rush into the

viewer’s mind without allowing time for preparation. Possessing certain power

and tension, the objects and landscapes in Lee’s photograph sweep the viewer

away.

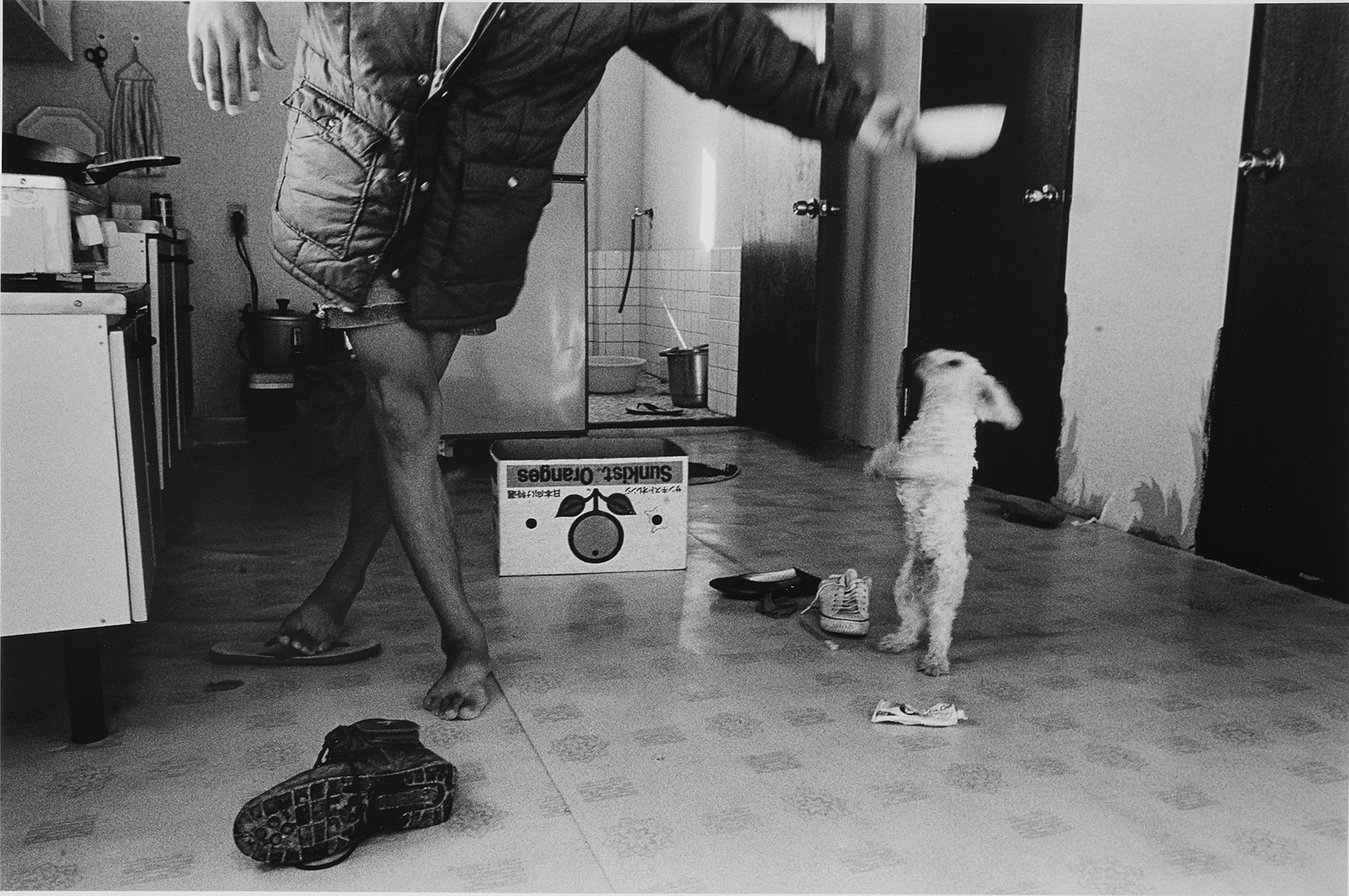

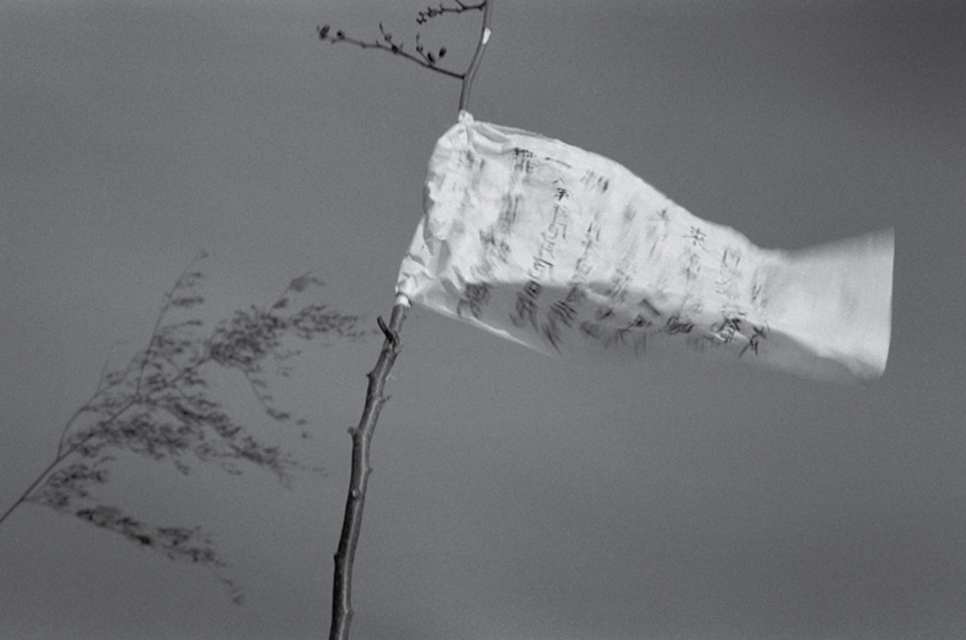

The

pictures, being more than an explanation, reproduction or an intended depiction

of a scene, alarm their audience in a somewhat violent manner. They are not

coordinated by the power of rationality but captured by instincts and the

subconscious. This is why the viewer momentarily plunges into an inner abyss

upon laying eyes on them. It is widely known that in most of his “dusky”

black-and-white works, Lee completely shatters every rule?clear shapes,

detailed and balanced composition applied to conventional photography, and

offers only rough elements.

The same holds true for focus, structure and

exposure: all of his photographs are either shaky or have their objects shoved

to the edge of the frame, their angles mangled or twisted out of perspective.

Instead of depending on objects, they potently display fleeting movements and

the dynamics of light and darkness. This creates a curious paradox: they show

that which is not in them. Not being an accurate record or reproduction of a

specific object, they present an entire, momentary feeling and atmosphere. They

prompt the viewer to comprehend and react to them not with eyes, but with the

mind, the memory and the subconscious. It may be possible to see them as a

roaring reproach from the photographer, a form of conundrum he is posing to his

audience.

Lee’s

photography is somewhat chilling and exceedingly dark with all of its objects

presented slashed up or shaken about. Its ferocity draws a sharp contrast with

those clear and bright conventional photographs characterized by idyllic

beauty, glamour and delicacy. The artist deliberately defies the traditional,

standardized language and techniques of photography.

While at work, his eyes

become more a part of the camera than of the human. He creates no distinction

between his eyes and the camera itself, and spontaneously snatches up

definitive moments of the world. Lee defines a moment as a transient instant

perceived by the eyes and mind and his camera naturally absorb it all. He

asserts that he seeks ultimate truth with his camera. He handles his camera with

this in mind. His quest is to convey the spirit that lies beyond a phenomenon,

to capture that which cannot be seen yet whose presence can be sensed.

His

photographs, composed with distorted view angles from a 28mm wide angle lens

and the grainy textures of high-sensitivity Tri-X films, stir up a violent

psychological anxiety in their beholder through daring cuts and frame

omissions. Fear and unease are provoked by the presence of an unidentifiable

object. The psychological order sustained by reason is shattered, lifting the

tight lid off the subconscious. Once this occurs, the searing energy of

primitive instincts gushes out, restoring once-forgotten memories hidden

beneath the conscious mind. His pictures revive this energy; they summon it.

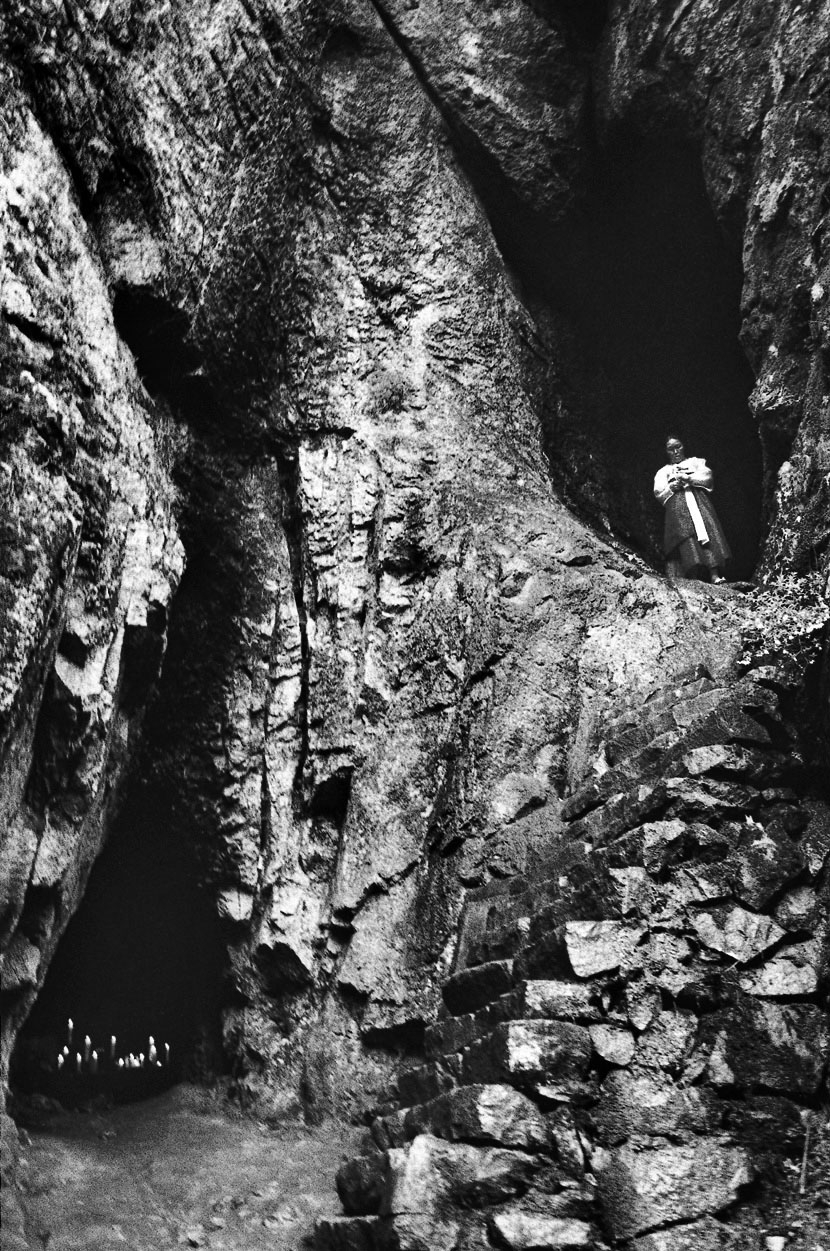

Lee’s

photography is soaked with the scents and vitality emanating from the numerous

objects he has captured after strenuously seeking them out. Reacting with

sensitivity to changes in seasons and conditions, time and place, the artist

works with firm animal instincts. His nose and “feelers” guide him to

locations. He hits the road when struck by a visceral sense that he will

discover the images he desires at a particular place and time. He has claimed

he can smell it, even in the city, and that he rushes to a location as the

aroma spreads.

The photographer attributes this feat to three years of

wandering around the nation. From 1992, he and others, poets, singers, painters

and sociologists traveled all over the country seeking out a variety of

cultural practices. His images bear the traces of this experience and the

rigorous training with his camera. Lee strives to attain enlightenment through

his camera and photography, which in turn is related to the disciplining of his

own self. He has mentioned in passing that he desired to be a Buddhist monk. He

does not view Buddhism as a religion; he considers it an integral part of his

life. It is a path towards knowing one’s true self, a method of

self-discipline, and life unto itself.

As

is commonly known, photography is a tool to accurately and mechanically

replicate a particular object. It reproduces what the eyes see, the world of

consciousness. Lee, in contrast, seeks to capture the so-called subconscious

world through his camera using these same qualities of photography. He adapts

the medium, a mechanical realization of the Western perspective, into a vehicle

that conveys the language and sentiment, feelings and spirit of the East.

One

could view this character as true modernity for Korean photography. I believe

it is the primary distinguishing feature of his work. Lee’s oeuvres are

contained in his book titled, ‘Conflict and Reaction’. Viewing the images

therein, any Korean would be able to perceive the swirling, indescribable

mixture of life and culture, grief and other emotions of all those who have

lived in this land. I appreciate his work, thick and dusk-like ink and ashes,

night and shadows. I like the landscapes and the faces of the Koreans in his

photographs, drenched in the energy and spirit that define the culture and

consciousness of those who existed here for ages.