A Very Common Point_Kwon Hyun

Bhin

In reality, even when we are simply standing still, countless

images, sounds, smells, tactile sensations, and other indefinable forms of

information pour in simultaneously. Yet we are not overwhelmed by this

bombardment of sensations. This is because, although we see, hear, smell,

touch, and feel, we do not judge each of these sensations one by one.

Nevertheless, it is certain that information from the external world enters

inward, into the body.

The “space in between,” where experiences remain as

undeniable facts registered by the body but are not consciously judged, must be

vast and infinite. For the sake of survival and stability, we select which

sensations to process first and postpone the rest. Busy dealing even with those

selected sensations, we momentarily forget that the postponed ones still remain

to be addressed.

Regardless of what outcomes it may eventually produce, this

inner world is a space universally shared by all. The most basic definition of

reality may be understood as “the facts one is currently facing.” The reality I

wish to pursue is precisely this busy, overcrowded reality described above.

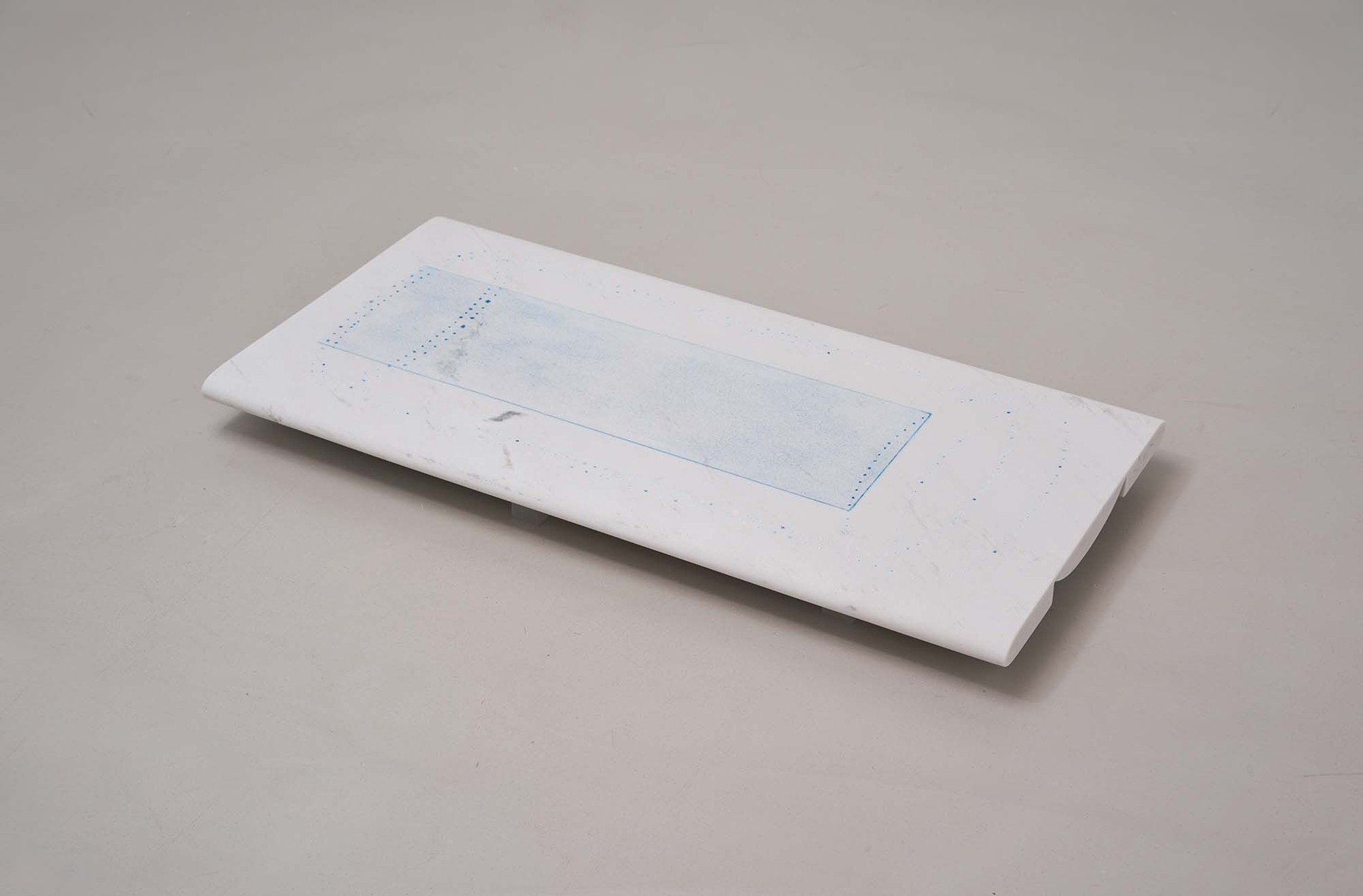

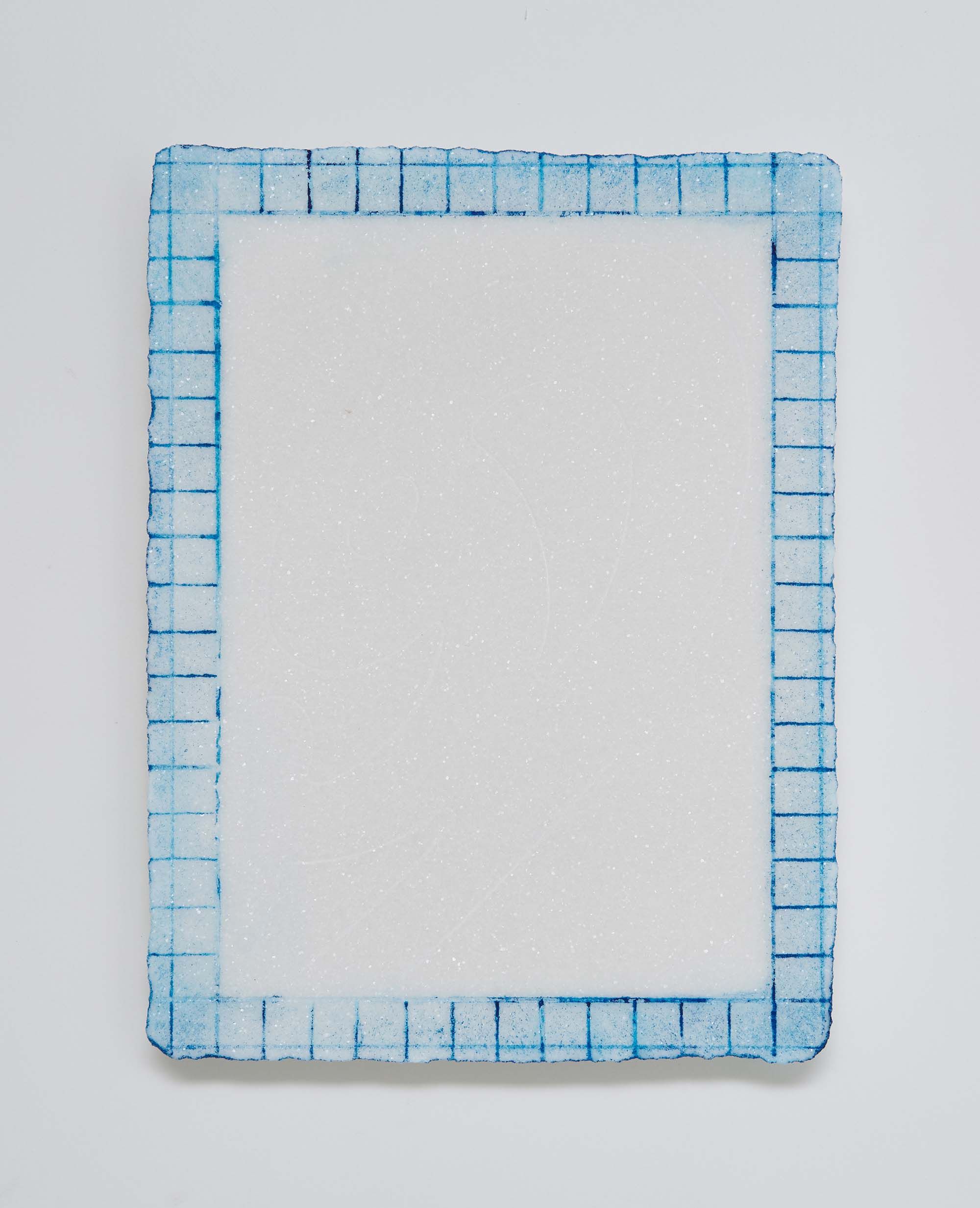

Events that occur in similar ways within similar spaces are

difficult to contrast because their differences are subtle. As a way to widen

this gap, I employ three-dimensional space (material). Reproducing experiences

or sensations within a space governed by gravity is highly prone to distortion,

yet at the same time it makes it easier to discern what feels right (closer to

the sensation) and what feels wrong (how far removed it is from the

experience).

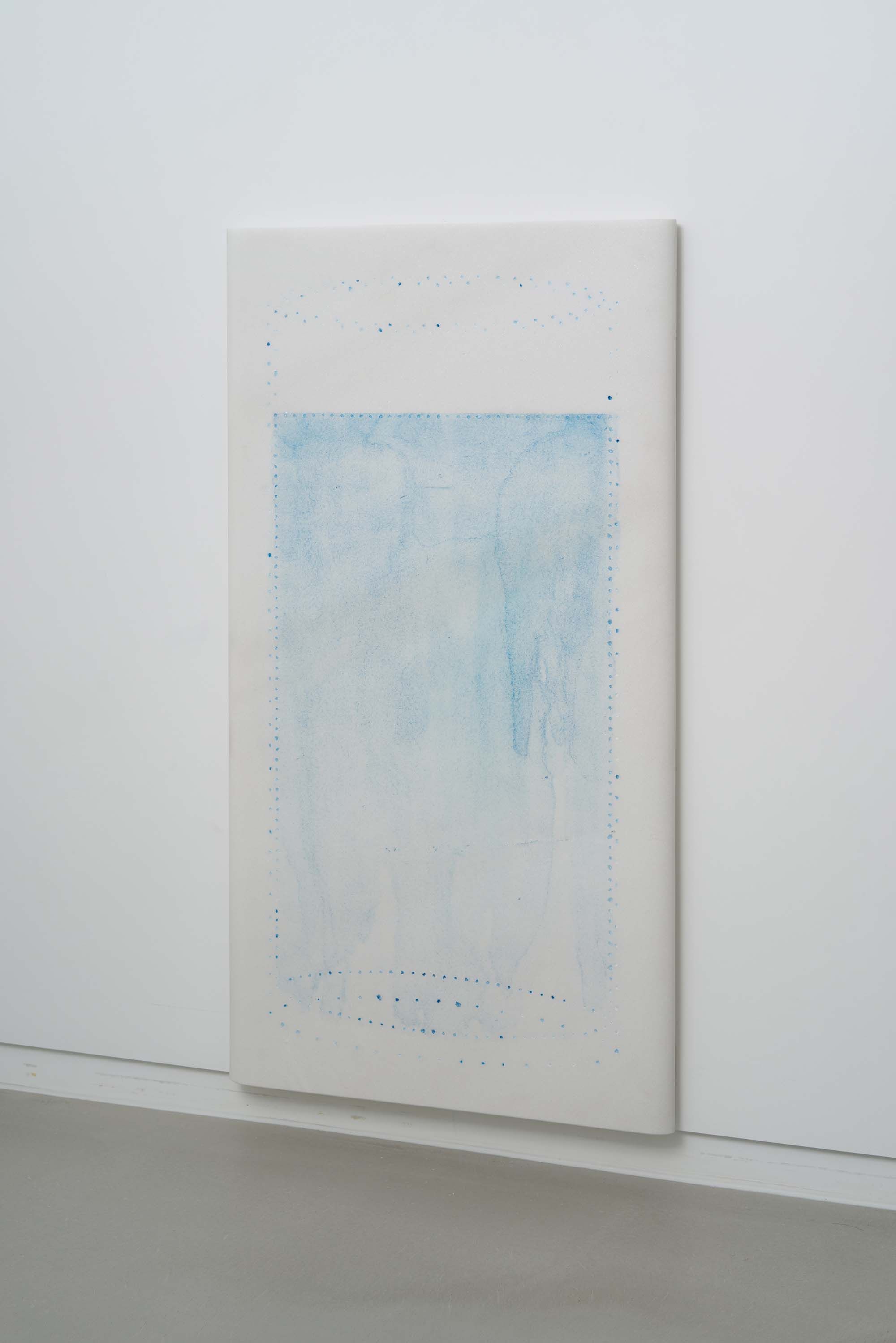

As a means of reducing the degree of distortion, I limited the

scale of my works. Human beings have limits defined by the body: a “comfortable

visual scale” and a “scale that an individual can control.” For instance, if an

object exceeds the scale of human vision, parts of it are inevitably omitted;

if it is too small, tools are required to enlarge it.

A magnified visual image

cannot be touched. Moreover, considering that sensation ultimately belongs

entirely to the individual, I believed it important to create conditions that

would allow me to work alone in order to practice precision in expression.

Therefore, I limited the size of my works to a range between approximately

“face-sized” and “the maximum height and width of a standing person stretching

both arms.”

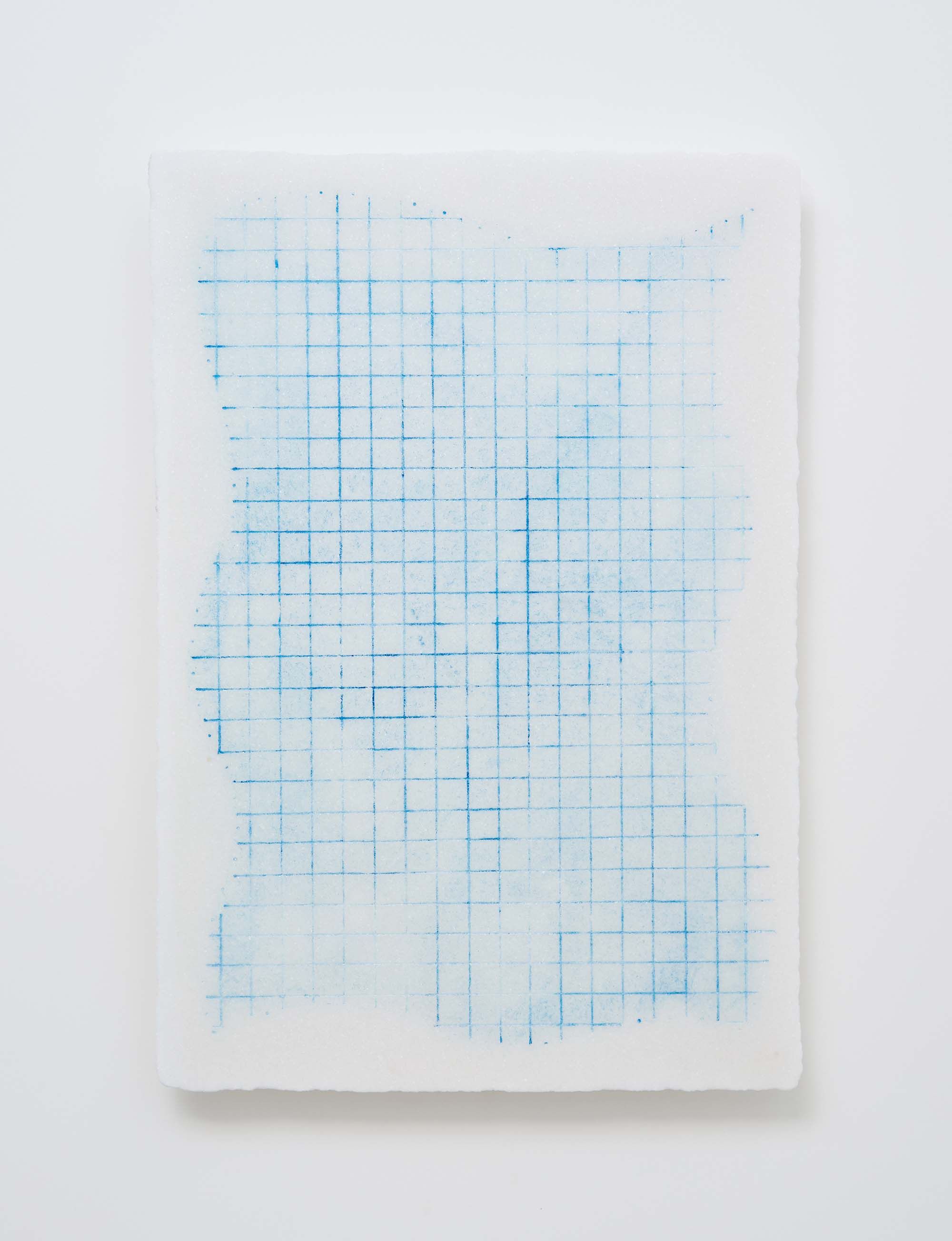

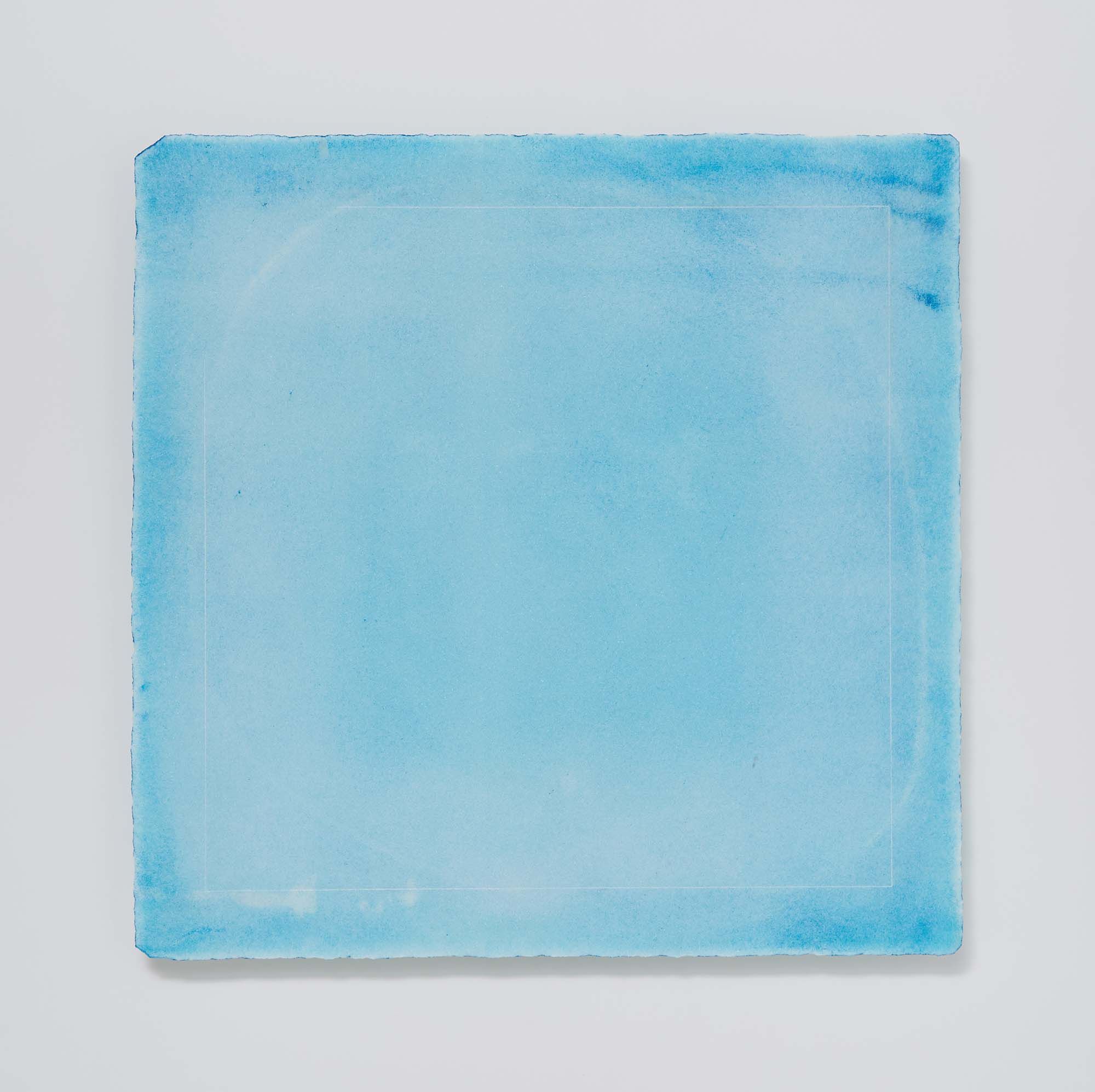

When an object has no objective form yet strongly suggests its

existence, its very lack of form and ambiguity make it difficult for the

observer to verify how they themselves perceived it. Regardless of whether it

is true or not, the outcomes derived from observing such objects at a

fundamental level are imaginings in which personal sensory experiences are

appended to the most universal phenomena.

Accordingly, the forms produced are

virtual images. Each resulting form appears complete and distinct as a sculpture,

while also being a fragment—a piece—that has emerged from the process itself.