1. Prologue: Note on Anachronistic Painting

Some

people might wonder why we should rethink works by Jaeho Jung at this point. Is

it because Jung has documented what has happened in our cities since

modernization? Or is it because he has pursued Korean traditional painting

which struggles to survive in contemporary art? Neither or both could be a

reason.

Apartments as subjects and Korean traditional painting have been

important features in defining Jaeho Jung as an artist. However, there are

already plenty of artists in the Korean art world raising questions about

apartments, architecture, and modernism. Also, he is not the only one who

endeavors to retain traditional painting in a modern way. If I had not seen 《Heat Island》1(2017), I too would have had such doubts. I mention this exhibition

at the very beginning of this essay because Jung became different after it.

As

we know, before 《Heat Island》 Jung

was an ‘apartment artist’; after it, realism appears prominently. This

exhibition, 《Rockets and Monsters》 (2018)*, solemnly addresses the latter. Since the late 1990s

his interest in reality has drawn him to cities and apartments to track

fragments of modernism which survive like ruins. He had to undertake all these

journeys to arrive at reality.

About

this time last year, he was painting buildings. He was painting a protruding

façade in detail, even the old stains, dust and dirt, each one with a detail

brush. Watching him doggedly painting his subject, I hesitated when it came to

deciding how I should perceive his realistic painting. Month after month

passed, and I watched him still concentrating on the same piece.

I was in

trouble. Isn’t his painting overly anachronistic? Continuing to practice

realistic painting in an era when representing things as they are is nothing

new, apparently indicates a determination to be anti-contemporary and

anti-painting. Isn’t he just practicing the grammar of anti-representation

which contemporary art has achieved—more faithfully and even, paradoxically,

more happily?

It may seem difficult to find any connection between 《Heat Island》which depicted shabby apartments

in Hong Kong and 《Rockets and Monsters》 . However, I will still attempt to link them in terms of their

anachronistic features and their pursuit of anti-contemporary performance. It

is evident that he has brought to light things overlooked by contemporariness

through his ‘overly, excessive painting’.2 In his new work,

Jung opposes contemporariness in a broader sense, incorporating temporality,

placeness, and the current painting norms.

2. An Exhibition without Apartments: Rockets and Monsters

In

the new work, there appear none of the apartments Jung is known for. Instead,

it deals with modernist architectures built in central Seoul in the 1960s–70s.

It includes film stills, cartoon rockets, advertising images and landscapes of

Cheonggye Stream seen from a rooftop on Sewoon Plaza. Some might wonder why his

characteristic subjects are missing. However, Jung has approached old

apartments not as a subject but as a theme that helps to make sense of the

period since the late 2000s.

By noting such changes, his work can be divided

into two periods. The first period, starting from his solo show in 2001, was a

journey during which his interest in cities gradually led him to delve into

places such as apartments and buildings. In the second, beginning in 2009, Jung

has focused more on the background of the times which such places connote.

Meanwhile, a turning point in his practice has recently emerged and this

is 《Heat Island》 in 2017. I

single out this exhibition as significant since the gap between the two axes of

time and place which had been getting slowly closer ‘became none’3 and

were ‘patched up’ through painting. If we only examine the title, 《Rockets and Monsters》 may appear to

have no connection with any of the other exhibitions. However, there are three

axes that closely interlock.

First

of all, the exhibition is based on a reflection on modernity. Regardless of

apartments, buildings, objects, place, and period, there is a consistent axis

of time running through his entire practice. Jung repeatedly looks back to the

1960 and 1970s when modernization was happening nationally, not to remember the

past but to examine the dilapidated landscape along with the remaining social

aspects of the time. Urbanization was a central feature of the country’s drive

to achieve rapid modernization, and architecture has been the façade of the era

in which such dramatic growth and great leaps forward were proclaimed and

flaunted.

In his new work, Jung focuses on the social imagination that

scientific technology promoted under the flag of ‘modernization of the

nation’. Analyzing media such as film, cartoon, and advertisements which were

communicating with the public, he investigates the ruins of the collective

dream of utopia. The somewhat childish title 《Rockets and Monsters》 came from what he

learned of the relationship between propagandistic social vehicles and the

public of the time.

‘Rocket’

and ‘Monster’ are metaphoric references to the illusion of modernity and to its

ghost, respectively. According to the artist, the rocket is a “dramatic

fictional symbol for an illusion of modernity” and the monster is “an entity

expelled from and discarded by the tides of modernization”.4 Nevertheless,

in the exhibition, the rocket appears as a physical object carrying materiality

rather than as an expression of a dismal ruin.

At the center is a lunar module

in three dimensions entitled Cast Away (2018).

This spacecraft, a colored paper model in a scene rather like a shipwreck,

emits smoke through a fog machine. At a glance, the piece could be mistaken for

a display in a science museum due to its presentation. The simple shape and

texture of this analogue reproduction are the sort of thing likely to be found

in a children’s cartoon. On realizing this, Jung consulted a comic book Yocheol

The Inventor, which he used to read in his childhood.

This book, published

in 1975 by a cartoonist Yun Sungyun, mirrors both the social aspects of

collective dreams and the illusion of scientific technology at that time.

Ruminating on this, Jung examines the gap between propaganda and reality around

scientific technology as well as a syndrome of the time when such a hope

floated about like some ghost.5

In

the cartoon, the rocket launch was not very successful. The protagonist not

only fails to perfect his rocket but also many different things: a flying

machine; oil extraction from garbage; space food; a time machine. His inventive

projects constantly fail. These failures, however, operate as a driving

force for imagination and the cartoon continues with the story of each new

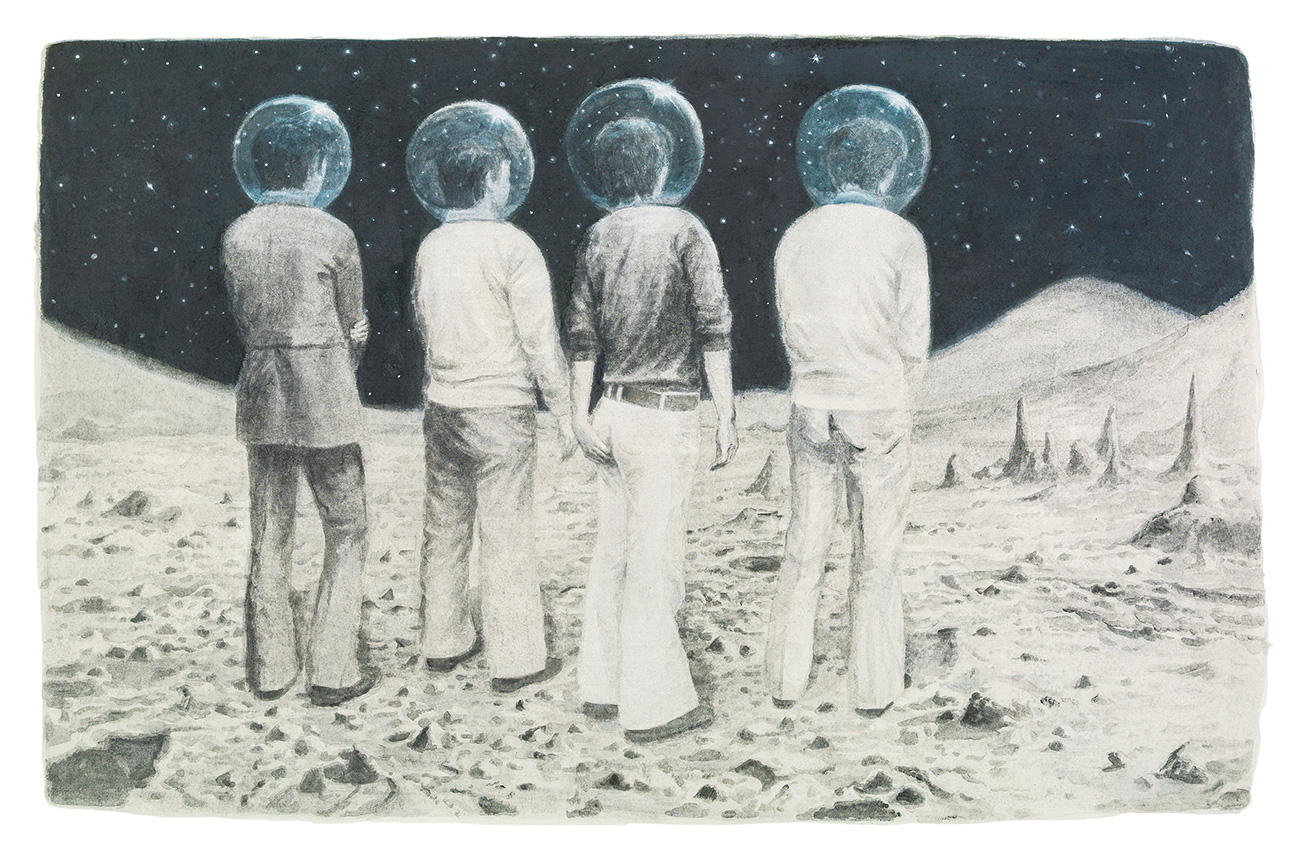

invention. Jung painted a scene where the rocket actually lands on the moon,

unlike the cartoon in which the protagonist’s attempt comically ends up

crashing into a stream. Imagining this in a real life, Jung situates the rocket

as if it is wrecked.

He pictured a rocket roaming and rusting somewhere along

the track of history and progress. This is neither a wish for scientific technology

nor a realization of imagination. Instead, it resembles the very illusion that

the nationally encouraged science and technology induced in the public.

The painting conveys a condition of incompleteness discarded by a society which

hurries towards the future. The artist would have wanted to embody an aspect of

the time that lost its way, by expressing a lost collective utopia with

the image of a wreck.

3. The Three-Dimensional as The Fundamental Quality of a Flat Surface: How

Did A Cartoon Rocket Become 3-D?

The

artist’s contemplation on modernity began in earnest with Father’s

Day in 2009. Since then, until Planet (2011)

and Days of Dust (2014), he had persistently

collected and painted scenes of the 1960s and 1970s, reflecting on “things

floating endlessly, corroded or decayed in the flow of time”6 caused by

the rapid economic growth which did not allow a pause to look back. We can find

the same rocket in one of the paintings during this period.

The rocket that

made an emergency landing on the moon in the painting Inventor

(2012) appears as a three dimensional object in this exhibition. The rocket is

found in three places.7 One is in Cast Away (2012),

another is in A Pilot’s Lab regarding the ‘Pilot’

fountain pen factory8, and the last is in A Ball of a Dwarf

which portrays a view from the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza. The appearance of the

rocket creates a route through the exhibition for the viewer to follow. During

a journey from ‘a machine wishing to fly’ to ‘a rocket lab’, there appears ‘a

girl dreaming of the promising future’.

Then, ‘a rocket which made an emergency

landing’ is encountered.9 This composition is in line with

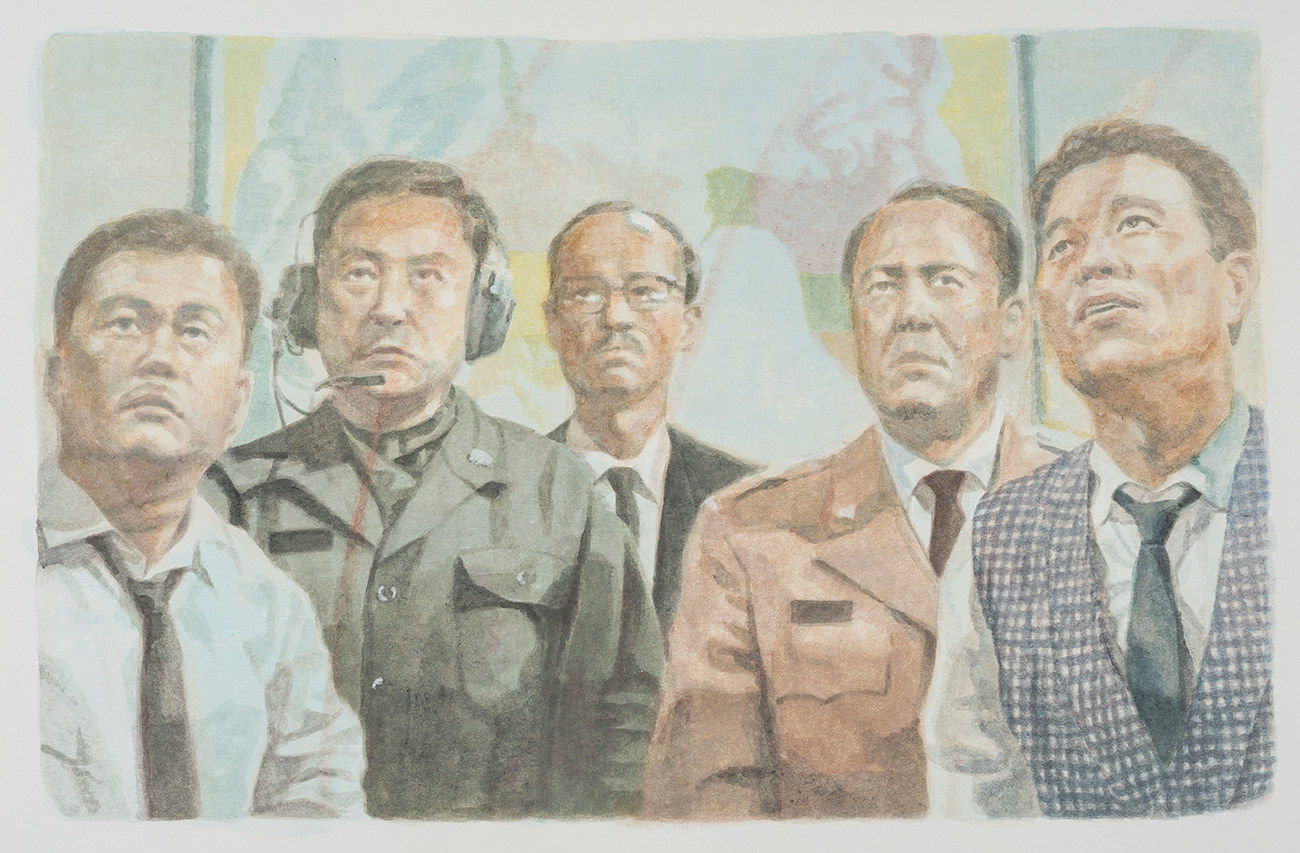

Jung’s works depicting scenes from popular films of the time. His blurry

paintings reinterpret images from films embodying melodramatic

sensitivity: Monster Yonggari (1967); Evil

from Space (1967); and Love Me Once Again (1968).

A dim afterimage is laid out on paper, consisting of modernity’s emotional

pleading intermingled with reality and fiction.

When

he planned to make a rocket out of paper, I thought it would be unsuccessful.

He cut up some paper and started to build a structure. While his plan was

gradually being realized, I noticed his voice was becoming more and more

excited, and sounded strange. He even experimented with a cigarette to create

smoke from a rocket which made an emergency landing. He did not look at all

exhausted despite the heavy workload; rather he seemed to have fun realizing

what he had imagined.

One month passed, then another and the rocket came to

look slightly worn-out and abandoned as if it had physically reacted to its

apparent condition as a shipwreck. It’s almost as if the inventor Yocheol is

resurrected through the painter Jaeho Jung. Even though the rocket drops from

the sky and crashes into a stream seemingly ending the play, the painting

restarts it in the next act. We need to pay attention to the subjectivity of

this three-dimensional sculpture. Jung could maximize the materiality of the

sculpture and its spatial situation in realizing the rocket. But, why does he

stick to the traditional method of painting which applies colors onto paper?

The

beginning of his three-dimensional work goes back to 2005 when he examined and

painted public apartments. He conceived paper monuments to commemorate old

apartments which had disappeared under the rationale of development. In 2005,

he made Daegwang Mansion Apartment in relief and Joongsan

Pilot Apartment in three dimensions. Since then he has created

more: Ahyun Apartment (2006); Monument

for Public Apartments (2005); Anam Apartment

(2006); Namdaemun Building (2007). These

three-dimensional works are monuments to the irony of places from the old era

that capitalist logic has neglected and treated as monstrosities. In this

exhibition, Cast Away shares the artist’s

enthusiasm for the monumental representation of loss and oblivion. All of these

were symbols of modernity and yet are now monsters of the old era that will

inevitably and gradually disappear.

The

way in which Jaeho Jung creates a three-dimensional object is not very

different from that of painting. He paints the skeleton of a building and adds

the surface and structural details to it. Cast Away went

through a process of making the texture and the shape more sophisticated than

an apartment in three dimensions. He cuts hardboard to make interior frames,

adds layers of paper for the surface and applies many layers of color to

express materiality and to produce fine details. The buildings and the rocket

are equally solid whether in two or three dimensions. Interestingly, the

solidity of the subjects is founded on these countless layers and the fine

details of each brushstroke as well as the whole structure.

The

threedimensionality of the materialized rocket serves to accentuate the

paintwork on every facet. Therefore, we experience and appreciate the

rocket by looking from every angle and through the accumulated layers of time

as well as peering into the surface, which is not how we see other three-dimensional

objects. Circulating around the subject, the viewer gazes at every face as it

appears.

Seeing it this way, even the dichotomy of being both flat and

three-dimensional is easily forgotten. The important point in appreciating

artwork is not to clarify the identity of the work as somewhere between a flat

surface and three-dimensional, nor to define what the painting is about. What

we can find in the relationship between the two lies in the question: “What

does Jung seek in his painting so that he can get closer to reality?”

4. Reconstruction of Perspective, A Head-to-Head Contest

It

is evident from his perspective that Jaeho Jung seeks reality. A survey of all

his work reveals that one particular viewpoint recurs in his painting. It is

frontality. Refusing the perspective which captures an object from a subjective

viewpoint, he uses frontal composition in order to face the object as it is.

This conveys his determination to depict the original object rather than a

view which stems from the painter who tries to grasp it. Jung has persisted

with this view which is present in his early work.10

In fact,

certain viewpoints are impossible due to the limitation of human sight. In

attempting to express architectural façades as absolutely smooth, Jung extends

his effort to using photography. He works to capture every detail of enormous

objects by thorough inspection of photographs in his studio; something which

our eyes simply cannot manage. Starting with overall impressions of the sites,

realistic elements are added and even distorted perspective is corrected. This

is a way to paint a subject objectively.

An

architectural reality is attained not by capturing perspective but from the

protruding structure on the surface of the building. What Jung pays attention

to is the three-dimensionality of the façade achieved through the structure and

surface. At first, such three-dimensionality is emphasized by the

structure—beam, wall, window, door—of the building. Then, our attention is

drawn to individual and collective descriptions that interpose themselves

within the gridlines of the façade.

If the gridlines symbolize a modern

enterprise and paternal regulation, the details surmounting them undermine the

dominant forms and diffuse the power given to the structure into a multitude.

This is linked to the flatness of the projected façade appearing subverted

in 《Heat Island》. His

practice of painting buildings, as in 《Rockets and

Monsters》 , spans 10 years between Ecstatic

Architecture (2007) and 《Heat Island》. As the grids, a symbol of the modern era, overlap with an

after-image of that time which seem like ghosts rising from within, the reality

of the buildings slowly emerges.

Jung’s

gaze was captivated by those buildings as he strolled around Seoul city center.

Mostly built between the 1960s and 1970s, the buildings reveal an architectural

style, then fashionable, initiated by Sewoon Plaza and Samil Building, two

landmarks symbolic of capitalist industrialization. However, what Jung’s

paintings contain are not monumental architectures as a representation of the

time but banal insignificant buildings encountered in our everyday lives.

I

would like to share a little behind-the-scenes episode regarding this

exhibition. The artist struggled to decide whether to call the exhibition

‘Architecture of Banality’ or ‘Rockets and Monsters’. In fact, the title

‘Architecture of Banality’ could embrace not only his new works but also much

of his other work. Ecstatic Architecture sees the

artist’s gaze overwhelmed by customary architecture as well as by the

wonderment of the subjects. The ‘architecture of banality’ therefore is almost

synonymous with ‘ecstatic architecture’.

In

the exhibition there are seven buildings with very ordinary titles: Namdaemun-ro

Building, Nodeul Town Center, Insadong Building, Cheongpa-ro Building, Hwanam

Building, Sogong-ro 99-1, and Sogong-ro 93-1.

These titles are either what the

buildings are actually called or official addresses. About his interest in

buildings, the artist says: “It seems, in a corner of modernization, in

architectures, I can see relationships like those between modernist

architectures and copies of them, aping or imitating them, illegitimates,

hybrids and so on”.11

Even so, he does not inject this thinking

into subjects. He restrains his personal impressions so as to express with

sophistication and as clearly as he can, reality. What he concentrates on here

is the elements of the surface composed of ordinary solid forms. He makes the

frameworks of buildings with a lattice of vertical and horizontal grids and

goes on to illustrate in fine detail, down to the finishes on paints, tiles,

bricks, or stones. The extraordinariness of ordinary architectures eventually

comes into view, as a ‘formal condition’ and a ‘social code’ are subtly infused

into the materiality of the surface.

5. Battle against Ghosts, Struggle with Materiality

Contemporary

architecture has been regularly renewed at the speed of capital. In pursuit of

sleek surfaces without frills completely, those architectures hide the

uncontrollable private areas. Recent buildings whose surfaces are fully armored

with more precise flatness and smooth tones rarely have protrusions in their

façades. In comparison, buildings from the 1960s-70s look old-fashioned and

shabby.

Amplifying the marks of the time which remain on façades as a living

element, Jung makes a strong stand against the ghostly nature of things

disappearing from real life. This is in opposition even to nostalgia or to

ruins which are today’s way to summon the past. This demonstrates the

‘existence’ of the being, rather than showing pity for the disappearance of these

traces of the modern era.

The

artist’s awareness of such matters is related to the ‘struggle with

materiality’ that he has experienced by retaining his identity as a traditional

painter. To unveil in minute detail a subject by carefully soaking it into a

paper surface might seem to be a tedious battle against ghosts. Jung describes

it as “a way to represent the death of materiality”.12

Noticing

the predestined ghostly nature of Korean traditional painting, he decided to

make the subject inhabit the existing surface as much as possible.13 His

attitude reflects his willingness to call on all of reality, like a documentary

painter or master artisan, by controlling even his own physical stance to paint

the subject objectively. This ‘labor-intensive’ painting, ‘anachronistic’ and

‘old-fashioned’ painting, as mentioned earlier, is the artist’s way of

combating the ghostly effect.

Let’s

go back to the question at the beginning of this essay: “Is his painting overly

anachronistic?” Jaeho Jung is not interested in atmosphere, aura, mood, or

message—things that the painting can change. He also does not appeal to new

visual sensations, trendy discourses or contemporariness. Instead, he asks:

“What can I do with painting, rather than meditating upon painting itself, in

order to question what painting is”.14

His laborintensive

painting, painting to faithfully represent the subject, leads to the subject

constituting a reality, ultimately the reality. Genuinely having to overcome

doubts one after another, from doubts about ‘painting’ and then about

‘painterliness’, he has labored long and hard to reach reality. What he pays

attention to is not concept or form but realism, which painting depicts. The

more the world is attracted to contemporary art with refined language and

forms, the more anachronistic his way of devoting himself to the subject

appears.

In

this way Jung’s painting evokes not only the places where Georges Perec15 obsessively

and minutely depicted so as to resist a loss but also the detailed descriptions

that Marcel Proust wrote to restore his childhood memories. His painting that

exhaustively lists even the smallest detail before surveying a subject, opposes

both a history of the modern era that is like amnesia, and contemporariness

whereby the near past disappears as residue.

It brings to light a reality

marginalized within dominant discourses and simultaneously summons the

daily narratives in the surface that were lost to our visual system. By vividly

demonstrating the materiality of the surface to his contemporaries who were

experiencing a loss of place, the artist determinedly opposes oblivion and the

overall syndrome of loss. So, in an anti-contemporary, anti-painterly,

anachronistic way, he continues his ‘overly, excessive painting’ to fight

against the errors and limits of ‘contemporariness’.

6. A World of Dwarfs and Giants: The Landscape Surrounding Sewoon

Plaza

“Now

I know this society is a massive monster. It is a massive monster wielding

frightening power just as it likes. My younger brother and his friend saw

themselves as oil floating on water. Oil and water do not mix. But this

metaphor may not be so right. What really frightens me is that, whether or not

the two admit it, they are trapped in the rolling mass.” –Cho

Se-Hui, ‘On the Pedestrian Overpass’16

One

day in June I went to the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza. I wanted to see a landscape

Jung was striving to complete down to the last detail. I gaze at a huge canvas

on which he has just started to make a sketch: A Ball of a

Dwarf, 2018. It would take at

least a month to finish that landscape. Around the same time last year, he was

stuck doing another painting of buildings. For three months he grappled with a

single piece to slowly add to paper things like stains, dust, rust, dirt,

dampness and shadow.

If I look back to that time, his current determination

might seem less resolute in comparison. A sheet of photo prints is on the floor

of his studio. It captures the area around Cheonggye Stream overlooked from

Sewoon Plaza. The neighborhood of Jongno street is full of skyscrapers yet the

area around Sewoon Plaza is densely populated with low roofs. It is surprising

that this kind of area still remains at the heart of an enormous city like

Seoul. Over the last fifty years, low-rise houses have been wiped out and

replaced by gigantic buildings. The remaining shabby buildings naturally became

dwarfs among giants. The low roofs seen from the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza

hug the ground like dwarf houses. This is central Seoul in 2018 as seen by Jaeho

Jung.

“From

the rooftop, it was obvious at a glance that the old neighboring commercial

district has degenerated into a slum. It means that this area was a slum at the

time Sewoon Plaza was constructed and is still a slum. By contrast, the plaza’s

newly-built pedestrian deck is too neat. I found it amazing. It was a landscape

resembling ruins at the heart of the Seoul metropolis.”17

Here

is the landscape surrounding Sewoon Plaza that the artist finds surprising:

Built in 1967, the shopping mall emerged in Seoul like a monster, advertising

development and growth, and has since been recognized as a concrete monument to

that time. This building, once called “a monster cutting across the city

center”18, dramatically survived the threat of being demolished. An

architecture cannot be understood alone and separate from its surroundings.

Propagating modernization, Sewoon Plaza stood in conflict with the adjacent

slums but now, fifty years later, it is only regarded as an outdated monument.

The dwarfs and giants of the past are both subject to the same fate in the fast

flow of time. They are all dwarfs eventually, even though they seem to create a

contrasting landscape in terms of scale and appearance.

Going

up in the lift to the rooftop of Sewoon Plaza, which is open to the public, you

see Jongmyo Shrine opposite. In the middle of Seoul, it is hard to find a place

where you can see the surroundings without obstruction from just a few floors

up. There are some places well-known for their great view of the city: the

33-storey Jongno Tower, the 63-storey 63 Building, the 123-storey Lotte World

Tower, and the 68-storey Tower Palace.

The cityscape from these super-tall

towers is only a forest of buildings. The higher the buildings soar into the

sky, the further the dwarf houses recede from human eyes. From the outset, the

logic of development does not allow them to be close to high-rise buildings.

The landscape Jung paints captures what has been excluded and vanished in a

city occupied by capital.

With

Sewoon Plaza at the center, the surrounding area is packed with temporary

buildings creating a slum-like appearance. Buildings in the area just next to

Sewoon Plaza are from 1900 up to the 1970s. The further away buildings are from

Sewoon Plaza, the more recent they are, providing a gradually developing

landscape. At some distance, Jongno Tower comes into view, and various

corporate buildings, hotels and offices stand in line. When Jongno Tower was

built in the late 1990s, people were concerned it would be a monstrosity

in Jongno Street.

On the other hand, they were happy to enjoy the view from the

top floor sky lounge on its completion. Human ambivalence is starkly manifest

at the moment of destruction or creation. If one stands on the rooftop of

Sewoon Plaza, to the left, Gwanghwamun gate comes into view beyond Jongno

Tower, and to the right, the scene unfolds toward Dongdaemun shopping center

over Gwangjang Market. Ignoring the magnificent panorama between Gwanghwamun

gate and Dongdaemun gate, the artist paints the other side—the right side

facing Dongdaemun gate.

If he had been interested in a contradictory landscape

and the spectacle of the city, he would surely have chosen the opposite side,

toward Jonggak. However, he intends neither to enjoy a city view nor to

represent a spectacle. He only wants to paint as realistically as he can the

reality of the subject that has overwhelmed him.

7. Detail and Panorama: Subverting the Politics of Perspective

“On

this side there are far more details. I can say, I am working on this piece in

order to capture these details—details that seem to have been spat out of the

roofs.”19 It was an intuitive response. Upon hearing my

question on his choice of a landscape on the right, he said “details” without

hesitation. The landscape of the roofs which overwhelmed him is far from sleek

flatness.20 It is chaotic, confusing and patchy like a rag. The

flatness appears because of the way our visual system works but the world is

not at all flat.

His three-dimensional work is nothing other than a paradoxical

expression to redress a reality that is compressed into flat surfaces. Slates

are laid like cloth patches sewn one on top of another; roofs are covered by

plastic sheets instead of being repaired; electric wires and piles of scrap

metal are tangled together; here and there are run-down machinery and pieces of

cast iron. White roofs have been changed to dull and somber brown, and where

thin paint has washed away, another color, that of rust, is produced.

This is a

color hidden from the façade and which has patiently endured the weathering of

time. Rusty water from a rusty roof together with leaking rain seep into the

interior of the building. The melting away of material nature carries on. The

low buildings have travelled the onerous path of the modern era and now expose

the difficult times that they fiercely withstood as if spitting their hardships

out onto their roofs. This is exactly the face of reality that contemporary time

has discarded; a rusty façade that survived in one of the humblest places.

Contemporary

cities with a disease of gigantism have concealed the messy truth of reality

with their colossal size and dizzying height. A magnificent panorama from these

buildings does not include dwarf houses. The contradiction and confrontation in

society that ‘A Little Ball Thrown by A Dwarf’21 discloses

still recur in our reality. In his painting A Ball of a Dwarf,

Jung also portrays a landscape of

confrontation between regeneration and alienation, concrete and slate, low

buildings and tall buildings, dwarfs and giants, and more. However, here his

intention is different.

He was touched not by a landscape of confrontation but

by the way in which both the ordinary buildings and the concrete monument they

surround survive together. Sewoon Plaza, whose name means “to draw here the

energy of the world”, once attracted people’s attention as an ambitious

modern project, but has been relegated to a relic of old times, now merely

signifying deterioration and collapse. This symbol of collapse is supported by

the rusting dwarf buildings which survive around the mall.

8. A View of a City as Opposed to A Panorama of Capital

Looking

down from the rooftop, the artist’s eyes are fixed on the surfaces of buildings

as far down as is possible, skipping the glorious vertical distance. His eyes

refuse to follow the city’s grand and spectacular panorama; instead his gaze

jumps across the distance between a city-scale view and an individual human,

the macro and the micro, and arrives at the surface of the subject. By doing

this, he undermines the authority of perspective and extensively exposes the

subject itself.

The reality he pursues is deeply related to the human visual

system. One day I had a conversation with Jung about an artist’s panoramic

photography. A 19th century panorama introduced by Zachary Formwarlt22 shows

a city of that time in ultra-high resolution, and raises the question: “Does

this picture convey a city view or a new capitalist system?” This question of

what the panorama shows us is reflected in Jung’s practice. He has created many

different cityscapes before arriving at a panoramic view with A

Ball of a Dwarf.

His interest

in this subject started with the nighttime view of Seoul from Namsan mountain,

presented in his first solo show in 2001. Then, it carried on through

landscapes around Inner Circle Expressway, Incheon, Cheonggye Stream23 and

Haebangchon. These panoramas embrace the artist’s mixed feelings and affection

for the disappearing places and gradually focus more and more on obsessively

revealing collective entities that comprise the overall gigantic view.

A

Ball of a Dwarf is his first panorama in 13 years. The previous

one was A Song for Gangbuk 24 in which

he depicted the Haebangchon area in 2005. Since then, Jung’s eyes have delved

into the inner city, not the outskirts. While the city’s physical appearance

was rapidly changing in reality, Jaeho Jung had been walking through the

inner city and had painted citizens apartments as well as the debris of old

buildings that have remained from the modern era.

During this time, what

emerged were old apartments, architecture from the 1960s and 1970s, worn-out

objects, and the facades of integrated buildings. His eyes were recording time

and space disintegrating and what he was seeing converged in A

Ball of a Dwarf. This painting has the structure of a cityscape, but

mostly focuses on depicting roofs in detail. The act of adjacent roofs

connecting to one another like a rag signifies more than encountering the

reality of the other side of the city. It evokes the true nature of the city,

the ruins of capital, the fallacy of the panoramic subject, mounting a

counterattack on contemporariness and establishing the objecthood of shabby

things.

9. Painting Working at Reality, Realism

“I

think capitalism might be afraid of painting somehow. The spotless white bear

in a Coca Cola TV ad would no longer be attractive to people who believe that

real animals’ bodies smell of all sorts and have dirt in their fur.”25

The

view overlooking the city informs a complete view of the environment. This

perspective leads to the illusion and misapprehension that the main agent (the

viewer) is at the center of capital, technology and the dominant ideology.

Today, an application like Google Earth offers us a fake experience with a

realistic panoramic view of places. Jaeho Jung’s urban landscape deconstructs

bourgeois ideology, which is associated with such a perspective, allowing us to

come face to face with its true nature via our senses and the materiality which

constitute our reality.

His painting removes the authority of the viewer who

primarily wishes to look at a subject in the distance. Revealing so much

detail, it also frustrates a desire to hold the subject in a comprehensive and

sleek impression. His ‘overly, excessive painting’ which the viewer may

experience as suffocating, above all, challenges our senses and our perspective

on capital which we embody. This style of painting has spread from Incheon to

Chenggye Stream, onto old apartments and building facades, passed through Hong

Kong, and so reached the center of Seoul.

A

Ball of a Dwarf illustrates a reality in which the landscapes of

real lives endlessly driven down by the preeminence of growth and development

are “sewn together”26 through exhaustive details in the

painting. The rocket launched into the sky means not only a collective dream

which cannot be mediated in real life but also a ball thrown high in the sky by

a dwarf living under one of the lowest roofs in the city.

Woven from a giant’s

view, a dwarf’s reality, and a monster’s failed flight, how contemporary this

landscape is! One might ask: Why has he created the rocket in three dimensions?

Is he absorbed by homesickness or nostalgia? Why has he depicted the subject

with such explicit details? As someone who has witnessed the process more than

once and up close, I only can say this: “Let’s just go in and take in the

paintings, what they contain.”

The artist’s intention is to rediscover the most

diminished value and unearth the reality of the subjects that has been buried

by fickle contemporariness in the age of capital and material. His

‘anachronistic painting’ evocatively portrays the realities which survive

in the disregarded subjects and consequently subverts the privileged

contemporary perspective which appeals to a sense of loss.

Using

his intense awareness of real life, Jaeho Jung defies the fictionality of retro

aesthetics which even capitalizes a syndrome of the time -like ruin and loss-

and discloses the entire reality concealed beneath the contemporariness.

Demonstrating a collective reality affixed to the façade (surface) with paint,

he attempts to restore realism into painting: “People do not want to see oil

floating in the sea.”27

Like a line in the novel, the painter

meticulously explores the shapes, grimy colors and even the stench of oil

rolling on the surface that people do not see. Likewise, he resists capitalized

views and institutionalized memory to divulge the truth of the subject and

works to narrow the gap between reality and painting. He performs his art so

earnestly in order to reconnect our perspective and very senses to reality from

which we have become detached.

1.

I interviewed Jaeho Jung three times in his studio on 25 April, 21 June, and 12

July, 2018 for this essay. Interestingly I visited his studio around this time

a year ago to write an essay for his solo show Heat Island (23 June –

18 July 2017, Indipress, Seoul). Our conversations on his art were through the

moments when two different times overlap and are collated in one place.

*This

is the title of Jaeho Jung’s works in Korea Artist Prize 2018.

2.

Sim Somi, ‘The Time of Loss, Resistance Through Painting’, Heat

Island (exhibition catalogue, 2017): “How much can painting function as a

visual sense to show reality? Now Jaeho Jung challenges aesthetics by painting

subjects which are poor, worn-out and neglected. This would be an artist’s

reflective practice on an aesthetic bridle which governs the limit of painting

and reality.”

3.

Here, by ‘became none’ I mean the state in which the axes of both time and

place are carefully and neatly interwoven and mediated, and their boundaries

are fused rather than lost or blurred. This is linked to reality ‘patched up’

with painting, which I will talk about later on in this essay.

4.

Jung quite logically explains this in his note: “When an Apollo astronaut

visited Korea, it was live on TV. A Science Expo took place, the urban

landscape rapidly changed due to massive architectural projects, for example,

the construction of Sewoon Plaza. Ordinary people were greatly affected by all

this and began to perceive this illusion of modernization encouraged by the

government. If ‘rocket’ is the most dramatic fictional symbol for an illusion

of modernity, ‘monster’ would symbolize unfamiliarity and the dark side of

changes encountered in everyday life as well as being the name of an entity

expelled from and discarded by the tides of modernization” (In the artist’s

note, 2018).

5. Yocheol

The Inventor was published in a supplement to Eokkae-dongmu for

two years from 1975. Eokkae-dongmu was one of the main children’s

magazines for the generation who went to primary school in the 1970s – 80s.

Remembering this, Jung scrutinizes the gap between the social imagination of

scientific technology and reality of that time: “In the waves of policies of

Park Chung-hee’s regime which promoted economic growth, science and technology,

children would have read Yocheol The Inventor, collected shoddy toys

supplemented by children’s magazines

like Sonyeon-Joongang and Eokkaedongmu, and dreamed of their

future. However, what they encountered when they became young adults was not

the bright future but a violent authoritarian society which oppressed their

mind and body” (In the artist’s note, 17 May 2016).

6.

See the essay by Jung Hyun in the catalogue of the exhibition Days of

Dust (2014).

7.

The rocket appears in the following three works: an installation

piece Cast Away (2018); and two paintings called A Pilot’s

Lab (2018) and A Ball of a Dwarf (2018).

8.

In April, 2018, local artists were invited to one of the Pilot factory

complexes in a suburban area of Seoul. The company allowed the artists to

collect things in the factory complex before its demolition. Jaeho Jung

happened to visit the factory at that time and conceived the idea of A

Pilot’s Lab. It is a surreal landscape in which the interior of an abandoned

factory mingles and overlaps with objects and images (things invented by

Yochel, model rockets, a monster Yonggari and more), as well as a half-eaten

snack left by the artist or the inventor.

9.

The display of works in the exhibition guides the viewer to the following

route:

Icarus (2018) → A Pilot’s Lab (2018) → A Bright

Future (2011) → Cast Away (2018).

10.

See an essay by Lee Yeon-Sik in Ecstatic Architecture (exhibition

catalogue, 2007). Lee mentions Jung’s perspective in his painting of buildings:

“By introducing this composition from which the painter’s perspective has been

removed, he draws a line between his painting and general landscape painting”.

11.

In a conversation with the artist on 25 April 2018

12.

In the artist’s note, 26 January 2017

13.

Sim Somi, ibid.

14.

During the conversation with Jung, we had to come back repeatedly to the

question about painting itself, “Architects do not show what architecture is,

musicians do not show what music is, do they? Then, particularly in

contemporary art, those art practices questioning what painting is, what

photography or sculpture is, have emerged as if they are the highest level of

art. I no longer want to invest my work with such questions of what painterly,

painterliness, painting means. It is only that I have something to paint and

have paintings as a result of painting them. I simply want to focus on the

subject” (in a conversation with the artist on 15 July 2018; in an email from

the artist on 23 July 2018).

15.

Georges Perec wrote in obsessive detail about structures, forms and objects

within a space, as a way to prevent oblivion. See La Vie: mode

d’emploi (Life a User’s Manual), 1978; Espèces d’espaces (Species of

Space), 1974.

16.

Cho Se-hui, ‘On the Pedestrian Overpass’, A Little Ball Thrown by A Dwarf,

Moonji Publishing, 1978, p. 146.

17.

In the artist note, 30 September 2017.

18.

‘A Monster Building Cutting Across the City Center’, The Dong-a Ilbo, 7

April 1980.

19.

In a conversation with the artist on 15 July 2018.

20.

Jung’s approach of seeking reality from details is linked to his notion of

creating apartments, buildings and even a rocket in three dimensions.

21. A

Little Ball Thrown by A Dwarf (1978) written by Cho Se-hui is regarded as

a “realist novel in broad sense” since it addresses a realist theme critical to

social issues and at the same time seeks a non-realist style. Traces of the

world where the dwarf is in conflict appear in Jung’s painting as architectural

metaphors in the form of watchtowers, chimneys, rooftops and so on.

22. The

Principle of Uncertainty (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art,

Seoul, 25 May – 9 October 2017). In this exhibition, Zachary Formwarlt

presented his analysis of a huge panoramic landscape photo of San Francisco

shot by Eadweard Muybridge. The panorama’s details contain information on

the emergence of corporations, the viewpoints of capitalists and a rail strike.

This topic came up naturally during a conversation with Jung at his studio on

25 April 2018.

23.

In particular, pieces depicting Cheonggye Stream (2003) capture

various views of the Seoul metropolis, bringing into focus psychological

aspects of the city where he still lives: A Song for Gangbuk, How Long

Would I … Here, You Are Leaving Now, and Oh! Cheonggye Stream.

24.

Gangbuk refers to the northern part of Seoul. [translator’s note]

25.

In the artist’s note, 29 May 2013.

26.

Kang Inhye, ‘Panoramic Vision in the Contemporary Art – Victor Burgin’s

Panorama Works as a Critique of Totalized Space’, Journal of History of

Modern Art, Vol. 41, July 2017, p.155. In this essay, the author used the

expression ‘sewn together’ to describe how Victor Burgin’s panoramic

photography weaves various fragments together.

27.

Cho Se-hui, ‘City of Machines’, ibid, p. 185