Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Cha Yeonså’s solo

exhibitions include 《Hum Bomb, Hum Bomb, Hum Bomb Hum》 (N/A,

Seoul, 2025), 《Feed me stones》 (SAPY

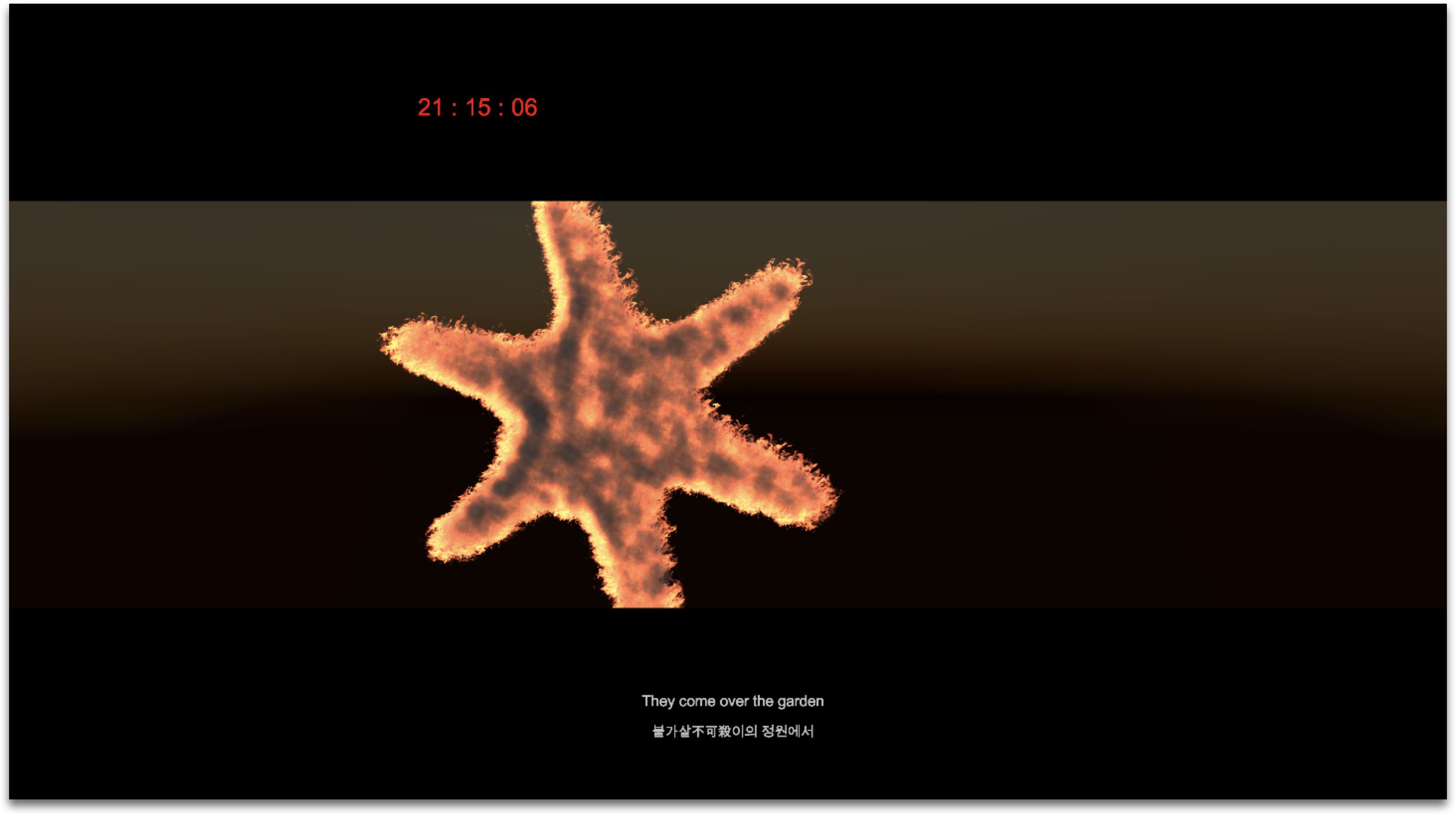

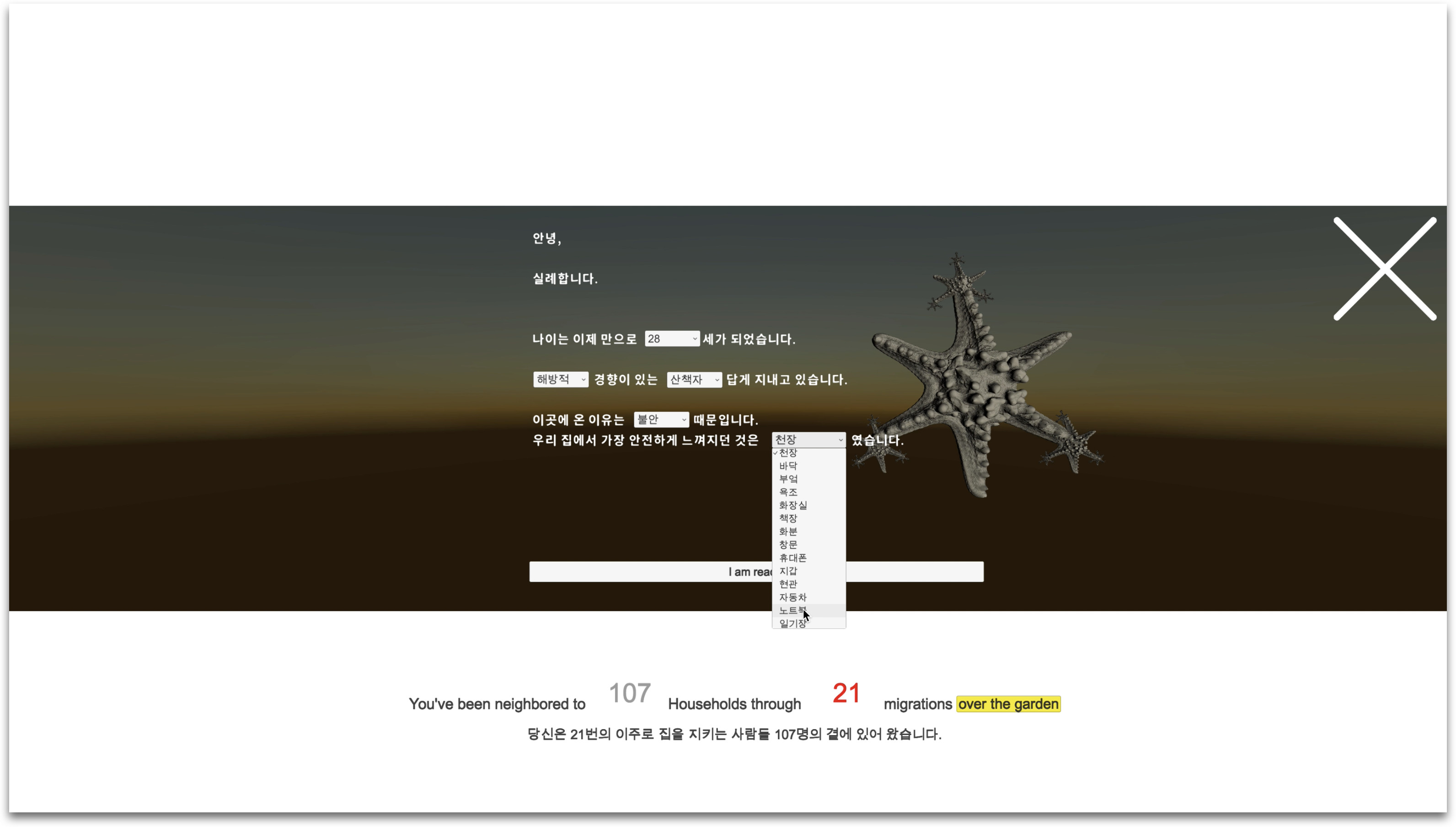

Gray Room, Seoul, 2024), 《KKOCH-DA-BAL is still there》 (Sahng-up Gallery, Euljiro, Seoul, 2024), 《This

Unbelievable Sleep》 (online, 2023), and 《Every mosquito feels the same》 (TINC, Seoul,

2022).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Cha has also participated in

group exhibitions such as 《sent in spun found》 (DOOSAN Gallery, Seoul,

2025), 《Tongue of Rain》 (Art

Sonje Center, Seoul, 2024), 《They, Them, and Them》 (Choi & Choi Gallery, Seoul, 2024), 《Sad

Captions》 (SeMA Bunker, Seoul, 2024), and 《The Motel: Because I want to live there》

(Misungjang Motel, Seoul, 2023). In 2024, she presented the live performance

heol, heol, heol at Frieze Seoul.