On

a gentle slope along Haedeung-ro in Dobong-gu stands his studio. The place,

resembling a small theater set, feels as peculiar as his art itself. Though

most people call him a photographer, I prefer to call him a rather unusual

painter — one who belongs simultaneously to Eastern and Western traditions. His

work is that original and fresh. Above all, he works as if he were a painter

who paints on canvas using a camera.

Globally

celebrated figures such as British pop icon Elton John have collected

his works, while leading institutions including the J. Paul Getty

Museum (Los Angeles), National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne),

and Yossi Milo Gallery (New York) house his photographs in their

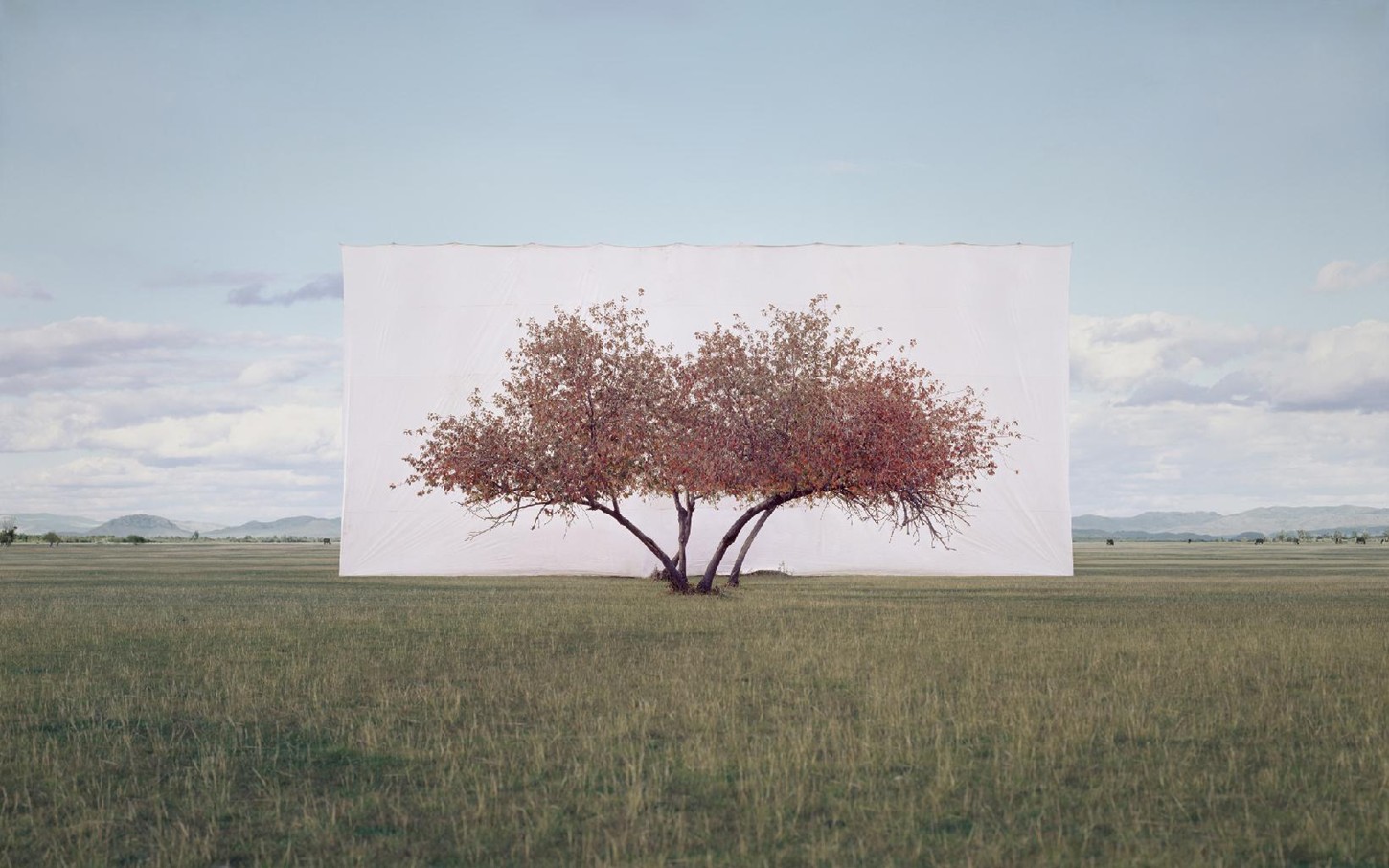

collections. Essentially, Lee photographs trees placed in front of canvases — a

“painter of photographs.” While his motifs range from desert landscapes to

reeds in Eulsukdo, the core subject is always the tree.

Once,

while sitting and reflecting during his student days, a tree “walked toward

him,” he says. That fateful encounter with a tree became the defining motif of

his artistic life — the beginning of his lifelong inquiry into images.

Lee

has said he first picked up a camera in search of answers to fundamental

questions about the essence of life. From this pursuit emerged the ‘Tree’

Series, in which he installs a white canvas behind a tree, transforming the

ordinary landscape into a poetic act of revelation.

By

isolating the tree from its original environment and granting it a new artistic

meaning, he pays reverence to nature while simultaneously exploring

representation and re-enactment. The result is one of the most acclaimed

photographic investigations in contemporary visual art.

For

more than two decades, the artist has carried these large canvases to sites

across the world. Like a painter standing before a blank surface, Lee positions

the canvas behind real trees, creatively reconstructing what traditional

painters once enacted through pigment. He continues to work with analog

precision, using a large-format film camera that demands meticulous control.

The

protagonists of his works are ordinary trees — unremarkable, naturally

scattered across the landscape — yet they become the central figures of the

white canvas’s stage. This is the essence of Lee’s art: revealing the

extraordinary within the ordinary.

The

first institution to recognize the true value of his eccentric vision was

the Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam, which devoted a feature to his works.

Since then, Lee has been widely introduced by the media as an artist who

conveys the spirit of Korean contemporary art to the world. His conceptual and

visual language fuses the aura and mystery of Oriental ink painting with the

structure of Western photography.

Hironobu

Shindo, CEO of Amana Holdings in Japan, praised Lee’s work for its

scale, balance, and perfection, noting that “the canvas, which has long existed

merely as a background, becomes a powerful presence in his art.” Indeed, a

nine-meter-high canvas created to frame a single old tree draws viewers into an

unfamiliar landscape. Within this new world that his canvas reveals, Lee

searches for subjects hidden from human sight — from palaces and street trees

to the secluded wetlands of Busan’s Eulsukdo.

Japanese

photographer Hosoe Eikoh once described him as “a creative and modern

artist who will mark a new chapter in the history of photography.” Lee stands

as a pivotal figure — one whose artistic journey embodies the poetic potential

of Korean art on the global stage.

He

has even compared his own work to a disciplinary process, much like the

meditative practice of Japanese modern philosopher Kitaro Nishida, who

viewed art as a path of spiritual training. Lee’s projects often emerge from

contemplating the silent inner world of the “painter tree” — a metaphor for the

unspoken emotions of beings that endure through time. He hopes his viewers will

listen to the stories of such witnesses who have stood for centuries in the

landscapes of history.

Currently,

he serves as Public Relations Ambassador of the Palaces and Royal Tombs

Center under the Cultural Heritage Administration, a position he will hold

until August 17, 2025. His recent works featuring empty canvases

themselves — as aesthetic and conceptual forms — have drawn attention for

transforming the very boundaries of photographic art.

In

these works, Lee calls forth and names those nameless existences long judged

only from a human point of view, overturning conventional notions of

photographic art. He strives to minimize the artist’s intervention, believing

that even a single canvas alone can embody art — much like a painter applying

pigment to a blank surface.

This,

ultimately, is a new revolution in expression — a creation of another

dimension. His illusionistic transformations, in which “nothing” appears as

“something else,” question the essence of both photography and art itself,

offering one of the most profound messages of our time.