In his most recent solo exhibition, Lee

Choonghyun juxtaposed a 3D figure in a computer program with a minimalist

sculpture, giving the visitor the paradoxical experience of the art exhibition

and sculpture as fictional entities. The artwork for this exhibition, which is

displayed in Museumhead’s outdoor area, has physical height but, at the same

time, does not bisect the real from the fictional or 3D from 2D. Trinity (2021)

looks like a geometric remodeling of three cubes from a computer program. It

may seem to be a modification of a common minimalist format. Ultimately however

it is not a simple juxtaposition of minimalism in 2D and 3D, it is the creation

of a perceptual and experiential substance. The two-dimensionality and

façade-emphasis of the screen and minimalism are replaced in Lee’s creative

process with diagonal, half-sided pieces that each have a different texture,

color, and movement. Placing three sculptures of the same style (but different

shapes) in a row brings to mind historical events that are characterized by a

repetitive or dramatic quality, which eventually leads back to discourse on the

replicable screens, plaza, easily-consumed ornaments, and 3D

installations/sculptures in public areas that are referenced (or intentionally

brought together in conflict) by the artwork. All of these things are made very

clear when a fictitious 3D object hurtles into, is replaced by something else

in, experienced in a real space or vice versa.

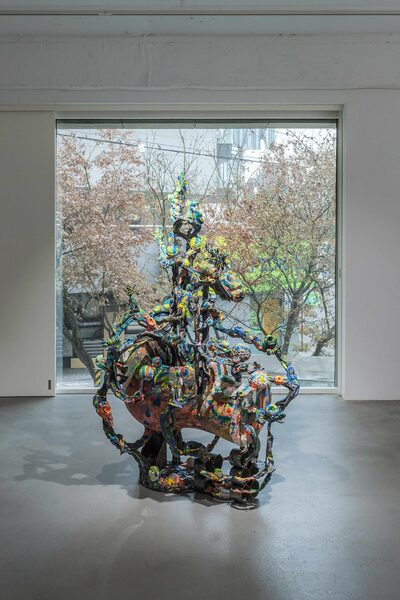

Oh Eun explores the formative Korean

sculpture, which seems all but discontinued in the current age, and its

monumentality within a 21st century context. Oh approaches

formative sculpture not from the perspective of tradition or historization but

as something that can be combined with a condensed version of her personal

experiences. In other words, it is the “commemorating of a commemorative act”—a

repackaging of attempts to overcome a particular situation, disaster, or

injury. It is in this way that the artist transforms Sohn Heung-min and the

injured human body into bodily movements that overcome the limitations of one’s

current circumstances. She also, as usual, includes a few moments of Korean art

history. Minor Injury (2021) refers to Bahc

Yiso’s gallery space of the same title, directing our attention current

discourses on othering, what it means to be a minority, and solutions/means of

addressing the needs of such groups. The body that has been segmented or

enslaved to disability that appears in Minor Injury and Last

Minute Goal (2021) brings to mind the human sculptures made in

the 1980s by Ryu In. Oh, who has studied art history extensively, shows us the

status of Korean art today, the as-yet unorganized accomplishments of Korean

art, and her increasing visibility as an artist that very much resembles a

last-minute goal.

Choi Taehoon blends commercial products with

sculpture’s functions and cultural status to create artworks that critique or

invalidate the sociohistorical context they are based on. His three solo

exhibitions, which have been held since 2018, featured creative

reconfigurations of the components of DIY products. In 《Tractor》 (2020), through which he was featured alongside curator Yoon

Min-hwa, Choi presented sculptures on the tension and energy that exists

between standardized objects and bodies (mannequins). For this exhibition, Choi

blends two disparate styles: the one from 《Tractor》 and the one that pervades 《Self-portrait》, a solo exhibition held in 2020. DIY furniture parts are joined

together horizontally and vertically in unconventional ways and the

standardized wooden pieces are imbued with a tense energy by draping them with

spray paint and body parts or clothing. The sculpture, which drew life from

clay and marble, is easily replaced with a mannequin, which ends up playing the

same role as the objects that are usually used to connect or prop up a

structure. The object-mannequins make us think about contemporary materials,

culture, and the imitations of movement—all of which are not at all related to

the idea of an “eternal body.”

By juxtaposing two seemingly disparate

worlds, 《Injury Time》 spotlights contemporary

sculpture as a medium that can be linked to or severed from the past. The

artworks in this exhibition overlap past and present, 2D and 3D, memory and

experience, and replication and creation. It often presents all of these things

as faulty statues of reality. Private and post-historical sculpture, which,

rather than being public or historical in nature, can be replicated,

copy-pasted, cropped or reconfigured at any time. In this way, such works are

declared as unique entities and achieve a mixture of diverse psychological

states and conditions. The five artists’ attempts to explore the past do not

end with lifeless reenactments of time or history: rather, they take on the qualities

of and showcase the current age as an onlooker of the past. They do not attempt

to build monuments to or try to write a full report of past truths. Instead,

they draw our attention to the endless conflict that history brings about in

its time difference with today. For the artists, the past is not a relay race

or a spatio-temporal entity of control or oblivion: it is our

constantly-intervening, discordant present. This is perhaps the point that this

exhibition strives most to portray. We too will have to keep striving to

discover how art is discrepant from a particular subject or time/space and

where and how such discordance is enacted in our present. The extra time that

this exhibition has done its best to embody is not a Mobius strip. It is a helical

space/time that produces discrepancy as well as spaces through which we can

escape from such limitations.

Kwon Hyukgue

(1. The above-mentioned article was published

in the Critiques section of Audio Visual Pavilion Lab (No. 4). Kwon

Hyukgue, “Injury Time,” Audio Visual Pavilion Lab (No. 4), 2020, pp.

81-88.)