Exhibitions

《TAXIDERMIA》, 2019.10.26 – 2019.11.30, N/A gallery

October 24, 2019

N/A Gallery

Installation

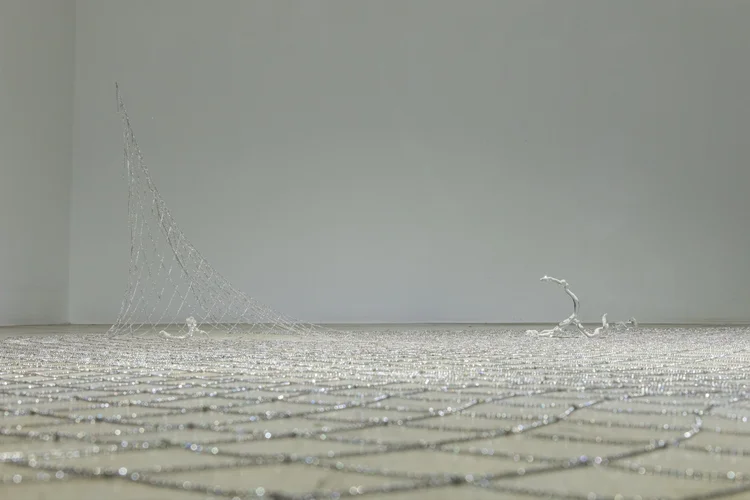

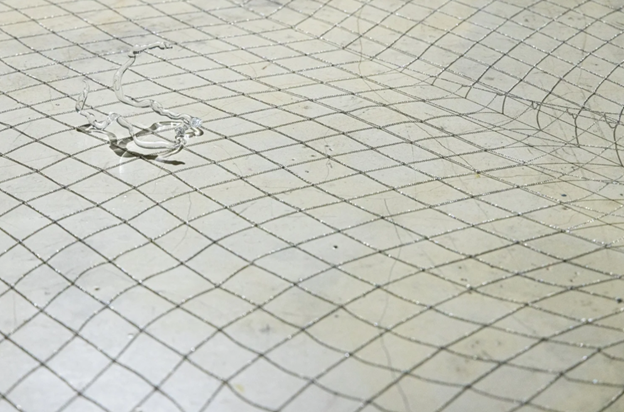

view 《TAXIDERMIA》 at N/A Gallery © Omyo Cho

TAXIDERMIA is a compound of “taxidermy”

and the suffix “-ia.” Taxidermy is the act of making a dead animal appear more

alive than it was in life. The suffix “-ia” connotes disease or a particular

state. In this sense, taxidermy is both ornament and luxury. It represents the

strange reality in which something that only appears more alive than the living

holds greater value.

Society is no different. We neglect the living and instead

assign meaning to the dead. We convert fleeting moments into images and revere

them eternally. Social media embalms fragments of a person’s life permanently. Politics, too, is remembered through isolated images. A taxidermied tiger

always appears to be roaring. In this process, life dissociated from images

goes unremembered—and what is unremembered is ultimately killed. The artist

calls this condition of a contemporary society that remembers only embalmed

images: TAXIDERMIA.

Installation

view 《TAXIDERMIA》 at N/A Gallery © Omyo Cho

Installation

view 《TAXIDERMIA》 at N/A Gallery © Omyo Cho

Images are born alongside death. A person doesn’t become a hero

because they die young; only those who die young can become heroes. Death

leaves behind purity; life, only disgrace. The image appears the moment the

real disappears. And because the real has vanished, the image becomes

unchanging and eternally preserved.

Art is no different from taxidermy. We say art transforms reality

into images. We say the essence of life is distilled in art. But just as

roaring isn’t the essence of a tiger, art does not contain the essence of life.

We merely believe it does. Through art, we convert life into images. People

dream not of the tigers languishing in zoos, but of a wild tiger roaring in a

place they’ve never seen. Yet that dream is nothing more than a dead ideal. We

may sing praises of life, but in the end, only what is dead holds real meaning.

In response, the artist turns to the alleys of printers

surrounding their studio and takes notice of the same objects discarded each

day. These reusable and replicable dead things are summoned back into the world

through the gesture of taxidermy. As such, these murdered objects reappear in

the exhibition both as embalmed images and ornamental artifacts. Through these

installations, the artist reveals how artistic practice hovers between acts of

embalming and presentation.

The artist collects dead materials, buries them in

clay and burns them, prints them onto paper, and enshrines them within the

exhibition space—a ritualistic performance that interrogates long-standing

practices of mourning and record-keeping. The gathered objects are taxidermied

permanently by the artist and embedded throughout the exhibition space. These

gestures endow discarded, purpose-made materials with new meanings, pointing to

the possibility of a post-human memory—one belonging to the things themselves.