In the 1980s, there was a man called Saemol-ajae (meaning Uncle

Saemol) in the rural village where my grandfather lived. I discovered that the

word “saemol was not really Korean, or even derived from Chinese characters,

but in fact connected to “saemaul” from Saemaul Undong, a community- based

rural development project initiated by the Korean government in the early 1970s

(also known as the New Community Movement). It seems that elderly people who

had poor hearing could not understand exactly what Saemaul Undong meant or how

it was pronounced, so they named it based on what they heard. As a result, a

young man who took the lead in activities related to the movement in this rural

village was called by this strange name until he died as an old man.

The years spanned by the grand discourses of history and society

are often contrasted with ordinary and trivial daily moments. We believe that

history is constituted only by particular individuals or certain extraordinary

moments, when in fact a society is a community comprised of individuals and

history is the sum of the accumulated moments of each individual”s life. With

the exception of a few figures, most of us are living lives that will not be

recalled in history, but historical events do pass through and leave their

traces on ordinary people. For all sorts of reasons, the majority of

individuals possess only delayed or restricted access to information about

social threats or sources of anxiety. In consequence, they are exposed to

unexpected dangers, and their lives can turn into situations over which they

have no control.

Shin Jungkyun observes the intersections of grand narratives and

individual lives and records and interprets these incidents from a different

perspective than that of an historian or a sociologist. One of his early works,

Universal Story (2010) focuses on the artist’s personal

memories from the military service required of South Korean men under the

conscription system. He retraces the route he used to take when returning to

base from the bus terminal. It is the artist’s personal recollections that are

being presented, but they resonate with viewers’ own memories and experiences.

Serving in the military is something that approximately half of the South

Korean population goes through. They find themselves in a situation in which

regional background and disparities in wealth and academic achievement no

longer matter.

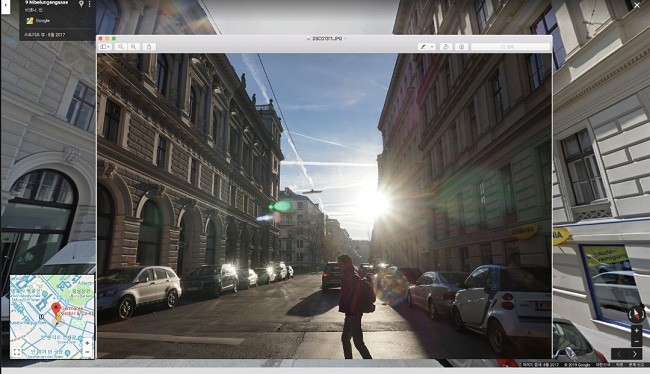

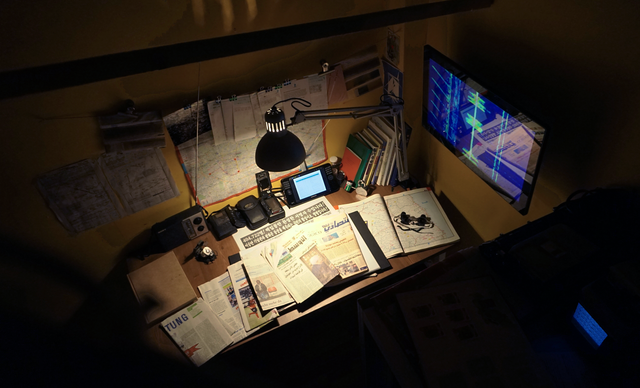

In Steganography Tutorial (2019), Shin works

in-depth with a deep encryption technique that serves to conceal confidential

data within photographic images or audio files so that it can be safely

delivered to its destination. There are still substantial traces of war that

drift through our society like ghosts and, on the other hand, all sorts of

incidents that are aimed at snatching away money, such as personal information

leaks, trades,

and attacks that are occurring online in real

time, as seen in the cases of physical marks of war left in places and of intense competition over the capital

on online platforms. These online attents that threaten us are often suppressed

or over whilst every North Korean crisis or the risk was highly emphasized

during certain periods including

election seasons and in specific places such as in the army and at reserve forces training centers. Shin

detects this dissymmetry and delivers tous feelings of anxiety and danger.

One interesting point with regard to how Shin shares these

feelings is that he sets up reversed situations. For example, he creates ironic

scenes that show a reservist who listens to a lecture on the dangers of a

possible North Korean invasion in an absent sort of way at a reserve forces

training area, or an internet user whose personal information gets stolen while

playing mobile games or conducting online shopping transactions. In addition,

he deliberately combines clashing elements in a number of works, including Silent

Dedication (2018), in which a tour guide introduces a space operated

by the former Agency for National Security Planning (now the National

Intelligence Service), invoking dark tourism; A Song Written in

Ongnyuche (2013), in which some parts of the lyrics of Growl, a K-Pop

song by EXO, are written in red in a North Korean typeface to seem like

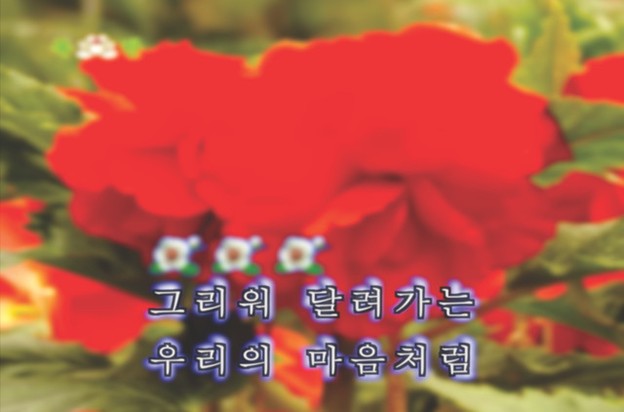

propaganda phrases; or Sing the Begonia (2016), a

single-channel video in the format of a karaoke video for a North Korean propaganda

hymn (in praise of Kim Jong-il).