Sculpture has recently been making a comeback in Korean art,

following painting. A growing number of artists are calling themselves

sculptors, researching new sculpture techniques and working hard to produce

powerful sculpture works. Several special exhibitions have highlighted their

work, either individually or collectively. But the term “comeback” implies that sculpture had

disappeared, and this claim is too easily refuted. How many sculptures have

appeared in our urban landscape since the Building Artwork Policy was

introduced, in 1995? It can safely be said that the production of sculpture has

never decreased in quantitative terms. But when it became a legal requirement

to insert sculptures into the urban scenery in affiliation with buildings, the

genre’s fate headed toward a sort of upside-down

ready-made. Things that should have been works of art were apathetically

produced and then neglected in non-artistic contexts where no one expected to

see an artwork, evoking a sense of skepticism about the very nature of art

among the few people who actually looked at them.

While the concept of creating a particular object known as an

artwork, based on traditional aesthetic media such as painting or sculpture,

cannot itself be wholly denied, it long ago started to be seen as somewhat

obsolete. In Korea, video and digital media emerged as new areas of interest in

the exploration of media at least as early as the 1990s, while there has been a

growth in works produced using various conceptual approaches that go beyond

medium-centric thought to reconsider the divisions of art itself. At the same

time, art galleries have changed from specialized and exclusive abodes of

artworks—as distinct from everyday objects—to open stages, allowing the symbolic, architectural and

performative arrangement of various heterogeneous items. This is a well-known

story. Relatively less discussed is the fact that, within this changed artistic

environment, creating sculpture has suddenly become an enigma. Many artists who

majored in the genre have avoided describing their works as sculpture, even

when these works are indeed three-dimensional; even more frequently, they have

expanded their work into media installation or changed direction altogether and

moved into video work.

It was in this climate that Minae Kim majored in sculpture, in the

mid-2000s. Over the past 10 years or so, while sculpture as an artistic topic

sank below the surface and then came back up, she has constantly explored

sculptural questions. But her approach is far from being one of dominating

spaces with monumental masses that redefine the concept of sculpture. On the

contrary, she recognizes a specific space for exhibition as a mold and pedestal

of sculpture, from which an eccentric object is drawn to subtly disturb the

order embodied in the space. In her works, sculptural elements have the

capacity to open and reveal the gaps between objects and space. They redefine

sculpture as a new issue, unconstrained by its traditional media—the totality of materials and convention to create an artistic

volume.

Minae Kim is known for work that cleverly latches onto the

architectural order which is physically constructed to program the types and

ranges of events in the space, then throws it into confusion, altering spatial

perception in unexpected ways. A typical example is Relatively

Related Relationship (2013), a work in which Kim borrowed

railings as a form and installed unidentified railing-type structures in

various places throughout the exhibition hall at MMCA Gwacheon as part of

the New Visions 《New Voices

exhibition》 (2013). Railings are normally devices

used to limit movement and prevent injury at points where changes in level

occur, such as flights of steps. But Kim’s

railing-shaped structures posed as safety barriers, preventing access to works

to protect them from damage by viewers, or confusingly blocked lines of flow,

or guided the eye along imaginary lines of movement, as if a path led up beyond

the ceiling, in the absence of an actual staircase. Such works reminds of the

tradition of the institutional critique, such as shutting exhibition rooms

completely or smashing up the floor, and of the phenomenological approaches

that cause viewers to newly perceive the exhibition venue as a purely physical

space. Yet they do not yield easily to such reductive classifications.

Just as Kim’s objects

belong in no specific category and constantly evade our grasp, so do her

spaces. At first, the artist seems to have recognized the space as a physical

and systematic institution, both an external environment and a framework

already internalized inside her, then attempted to explore this confining space

through sculpture. As an MA student, she attempted several works made from

boxes featuring cutouts exactly the right shape for holding specific

sculptures. In some (030516, 2005), the sculptures are

inserted into the cutouts; in others (040111, 2004-7), they

have come out of the boxes and are staring blankly at the empty holes from

which they have emerged. Finally, the sculptures disappear completely, leaving

several hundred empty boxes with cutout profiles of figures waving hello or

goodbye (Hi-Bye, 2006-7). The link between objects and space

is not one of ping-pongesque reciprocity in a single place, but one that

advances constantly to new places and changes constantly into different forms.

There is more than one way to move from here. Kim could have gone

beyond sculpture, or left art altogether for the world outside. She didn’t, but that does not mean we should jump to the conclusion that she

failed, ultimately, to escape the yoke of the system. Rather, Kim has driven

her own vehicle of space and objects, a strange contraption with a wheel on one

side and a brace on the other, tottering around wherever she wanted to go.

Though she herself does not claim to have been exploring sculpture until now,

she has maintained a constant awareness of the rules that define the

sculptural, at once reflecting them and working to find oblique angles of

escape from them. Because each of her works began with different,

externally-determined conditions, it is hard to sum up her entire trajectory in

a single chronicle. But Kim has developed types of technique in response to the

contexts of their work, and it is possible to trace the paths of these types as

they evolve through constant repetition, or undergo unpredictable

transformations.

First are works that send contradictory signals between movement

and stasis; works that, put simply, represent situations of stalemate. By

adding to an existing space a minimal number of objects imitating the

architectural elements around them, Kim creates situations where all directions

are open but we do not know where to go (Blind Alley, 2010),

or where we are given a clear direction in which to go, but no way of doing so

(Distant Stairway, 2011). The objects she has introduced are

thus similar in outer appearance to functional objects but useless. This effect

finds its most extreme expression in Rooftoe (2011),

an imitation column, added below a truss where no column is needed, with a

wheel at its base. At first glance, the work looks like a column that must stay

in place, without moving, but it does not actually need to be there. It stands

there, neither a proper object nor a meaningful architectural element, while

the red wheel at its base serenely bears the burden of twofold redundancy.

This approach, mainly formed at Kim’s college while studying in the UK, was both a response to spatial

programs for producing work and training artists, and an exploration of the

impossible position for sculptures as neither everyday items nor architecture.

Moving further towards works for exhibition halls, the self-denying qualities

of objects grow stronger. Here, we find structures that fit perfectly into the

square corners of the room when stood up, but have only one leg, with a wheel

at its base, so cannot stand up by themselves (A Set of Structures for

White Cube, 2012), works made from three connected wooden crutches

that can stand up by themselves but have lost their original function of

movement (Free-standing Sculpture, 2012) and works that

invalidate their own specificity by accepting all the functions and meanings of

objects that are legally allowed into the exhibition venue (Golden

Pillars – Table, Plinth and Object, 2012).

The artist did not stay for long in this blind alley in which

objects had to assert and prove themselves. By this time there were already

plenty of venues that, unlike classical White Cube with its principles of pure

space exclusively for exhibiting artworks, upheld the historical character of

their locations and the architectural qualities of their buildings, opening

themselves to extra-artistic contexts. This provided Kim with room for new

experimentation. She focused on making objects abandon the will to move or its

opposing lethargy, physically or virtually reflect and multiply the spaces in

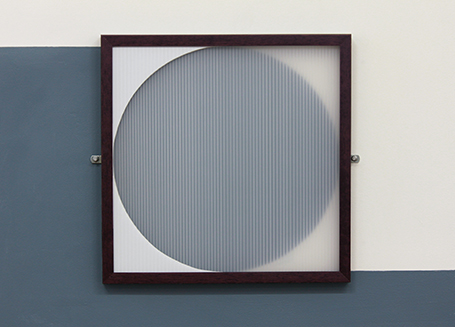

which they were placed. To this end, she introduced walls and curtains, windows

and mirror frames, or simply flat objects of various sizes, transparencies and

reflectances. The forms of fake windows recur with particular frequency. Kim

installs framed canvas and lighting in the shape of windows on the inside and

outside of an external venue wall (Behind the Scene, 2012),

or hangs a mirror on the front and back of a partitioning wall between two

identical police cells (La Reproduction Interdite, 2012),

creating the illusion of a window. Such devices, as intended by the artist, not

only deceive the eyes of viewers but function as a type of public screen,

inducing viewers to imagine what lies beyond them—spaces that do not actually exist and therefore cannot be confirmed.

Strictly speaking, these were not completely new experiments but

repeat attempts at the approach taken by Kim in 2008 at her first Seoul solo

exhibition, 《Anonymous

Scenes》. But while in 2008 she focused on materially

presenting the spatial illusions she had experienced around her, and the

fantasies they triggered, within the exhibition space, her works this time

adopted a structure that was comparatively open to the unknowable memories and

imaginings of those passing through the space at that moment, including the

artist herself, or those who had occupied it in the past. This approach was

further solidified in 2013’s Richard

Smith, a one-day project in collaboration with curator Kwon Hyukgue.

For this work, based in a project space at a shopping arcade in a residential

area due for redevelopment, Kim posited an imaginary figure who had lived in

the neighborhood and created ambiguous situations that allowed viewers to

imagine meeting him. Here, the artist and viewers were placed in the same

predicament of having to conjure an image of an unknown being based on only a

small handful material remains. Ingeniously, the entrance to this space, with

its shutter half pulled down, bore a strong similarity to Continuous

Reflection, a work displayed at Kim’s 2008

first solo exhibition, in which the artist installed mirrors on the exhibition

space wall and pulled shutters partially down over them, reflecting an earlier

experience in which she had mistaken the corrugated pattern on a wall for a

shuttered door. To those who remembered the 2008 work, this produced the

fantastical feeling that the space beyond the mirrors back then had transcended

space- time and opened out in London.

Creating such virtual leaps and jumps has been a key driving force

in Kim’s subsequent works. The huge pink and black

rubber balls that appeared at her at her second solo exhibition, 《Thoughts on Habit》 (2013), implied a

new kind of motility, able to roll or bounce off anywhere. These elements

appeared repeatedly in subsequent works, changing form into guises such as

immaterial light-based images (Black, Pink Balls, 2014),

graphic surfaces stuck to exhibition space walls (Conditional Drawings,

2015) or small, hard snooker balls (Black, Pink Balls,

2018). Just as divining the future in scattered rice grains is closer to

resolving compulsive anxiety about a specific future possibility than to

actually reading the future, these balls deliberately introduce randomness,

rather than being mechanically subordinated to the given conditions and

responding routines of the artist’s work.

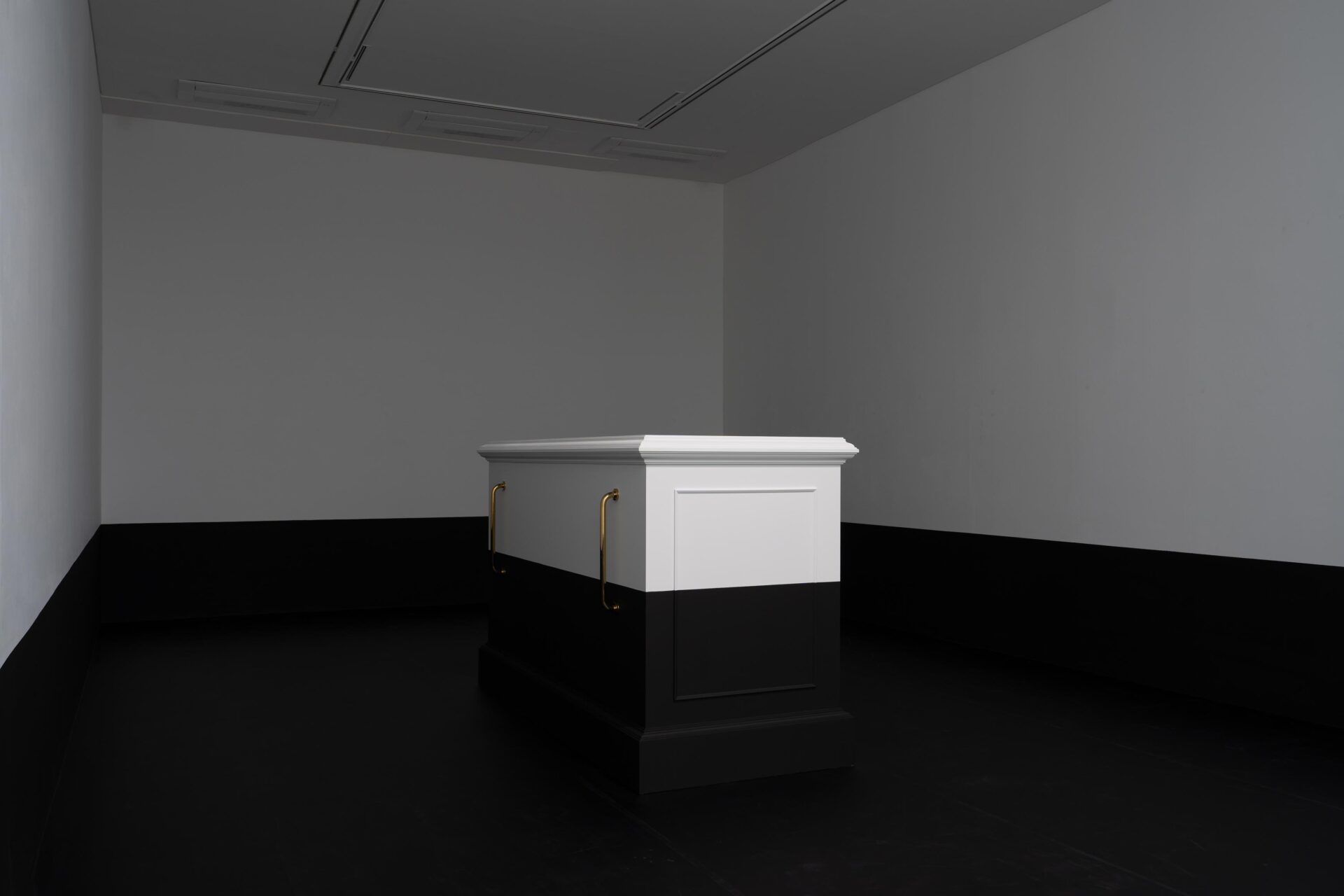

Recently, Minae Kim has focused not on physically occupying space

but on emptying it as far as possible while evoking strange thoughts,

impressions or instructions that swell like phantoms within it. In her 2018

exhibition 《GIROGI》, she used unexpected methods to transform the exhibition space into

a kind of moving image. Generally, white outlines of birds that appear fat in

comparison to the size of their wings are expanded to fill the walls,

irrespective of their original sizes. Moving light and sound give the

impression that the birds move momentarily though, of course, this is not

actually the case. While, in several senses, the question of how sculptural

things could move is one that ran through Kim’s

previous works, 《GIROGI》 offers

the most recent answer. Sculpture remains in a liminal space between

agoraphobia and claustrophobia, leaving us uncertain how to feel. But within

this space, it moves endlessly. Whether we must call the results of these

movements sculpture or see them as the invention of another medium, has yet to

be decided. It seems, perhaps, that the artist wants to leave it undecided for

as long as possible.