When one arrives in a

new place, one does not only discover a new geography, a new space, but also

new temporalities, and the difficult dynamic arrived at through agreements and

through conflicts and tensions that configure the coexistence of different communities

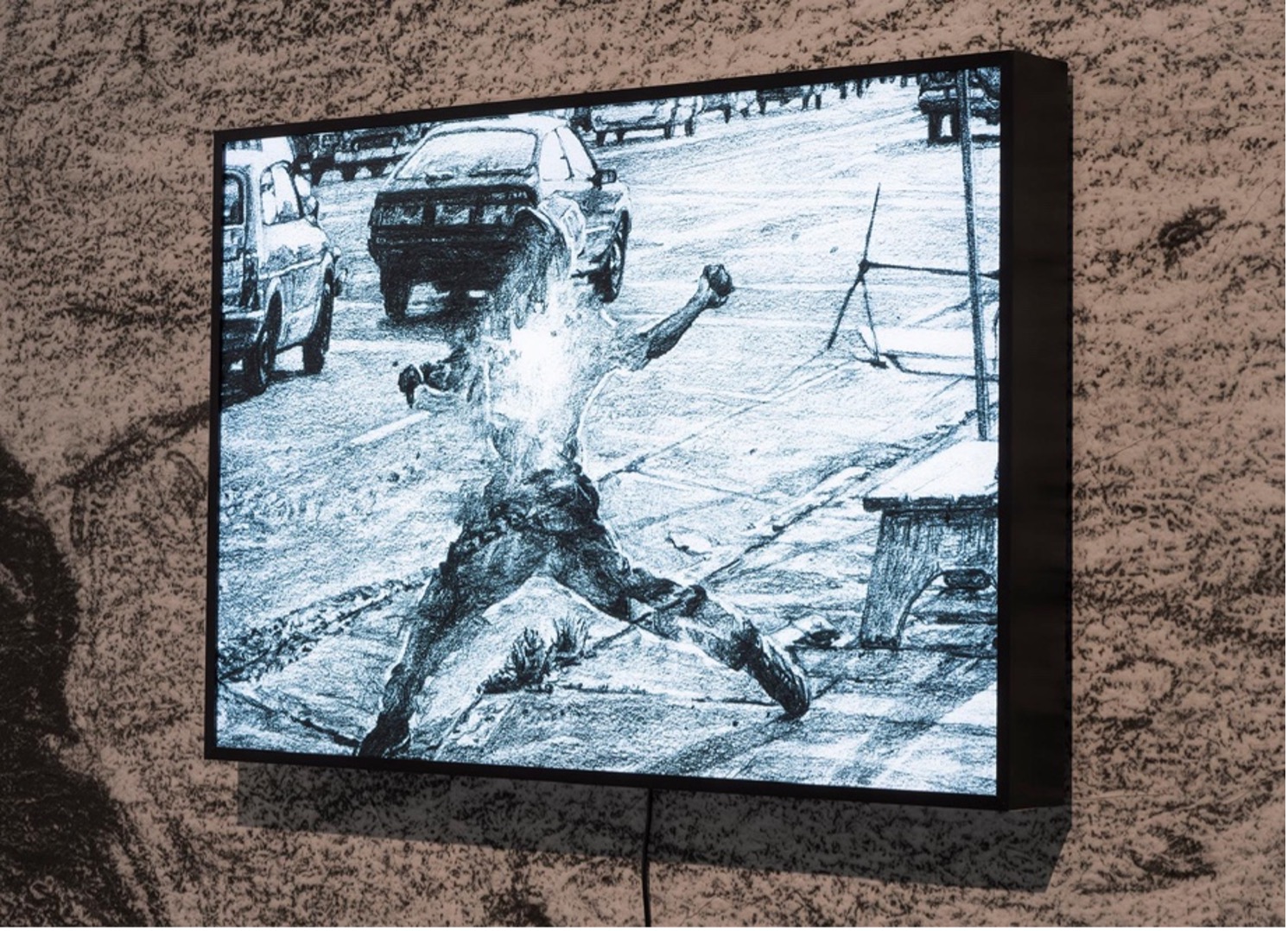

in an urban space. Perhaps one of the most dramatic and agonizing moments that

the Central American community has faced in Los Angeles is the L.A. Uprising in

1992 after the infamous verdict acquitting the police officers involved in the

brutal beating of Rodney King. During the upheaval, the parts of the city most

affected were South Central, the Pico Union neighborhood, and Koreatown. As it

happens, many Central Americans lived in these neighborhoods. Shops were burned

down, the police unlawfully detained and deported innocent bystanders, and

chaos reigned for a few days. The police protected the Westside neighborhoods,

but in the meantime, poor Black, Korean, and Central American residents

suffered the destruction. An event such as the Uprising of 1992 is easily found

in any contemporary history of Los Angeles or even of the United States.

However, the transformation of this event into a document or a monument, into a

milestone that cannot be forgotten in any writing of the city’s history with a

capital H, does not make it any less relevant to a reconstruction of material

memory of a community. This event undoubtedly marked a “before” and an “after”

in the manner in which the Korean and African American communities coexisted in

this city and the manner in which ethnic groups settled in the urban space. The

task, then, that this type of event imposes on material history is the rescue

of other layers of meaning, other experiential sediments that suffered the

impact of this event but whose memory has not been recorded in the official

record. The temporality of politics and biographical time collide. By

reconstructing these events through a notion of material memory, we have to

establish that the political event that the books commemorate was constructed

upon the erasure and destruction of other material sediments that served to

organize and give meaning to the biographical time of many eyewitnesses.

If in revolutions the

written word precedes reality, then words, discourses, and ideas come before

action. In revolts, however, the actions of hundreds of men and women occur

before words or images have proposed a codification or a way to make these actions

legible. To recover the history of a revolt, to trace its cartography, requires

putting together a puzzle that comprises every history, composed of hundreds of

pages torn to pieces where desires, aspirations, dreams, as well as

frustrations and resentments come together. The ripped pages are not discourses

or ideologies but the blood, sweat, and tears which constitute the magma with

which history is written, especially if this history was born out of a protest

or an insurgency against an established order that is considered arbitrary,

unjust, or tyrannical.

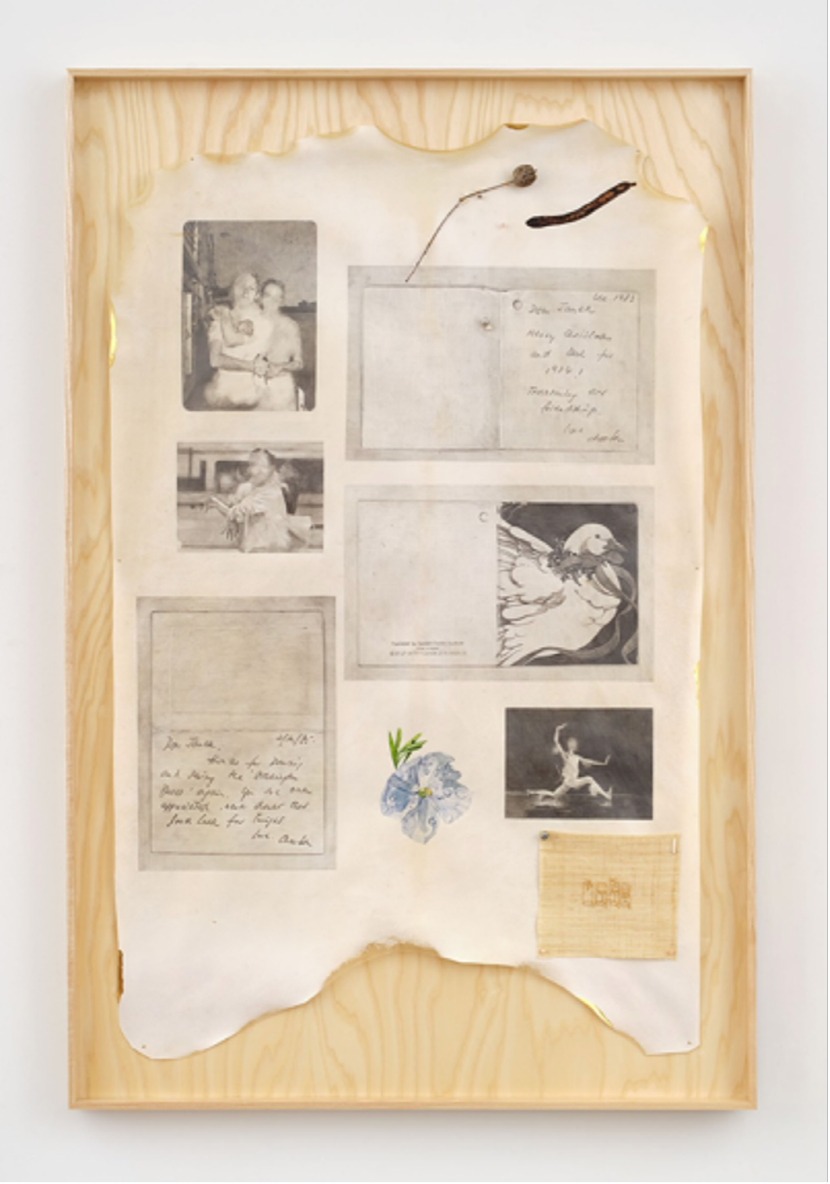

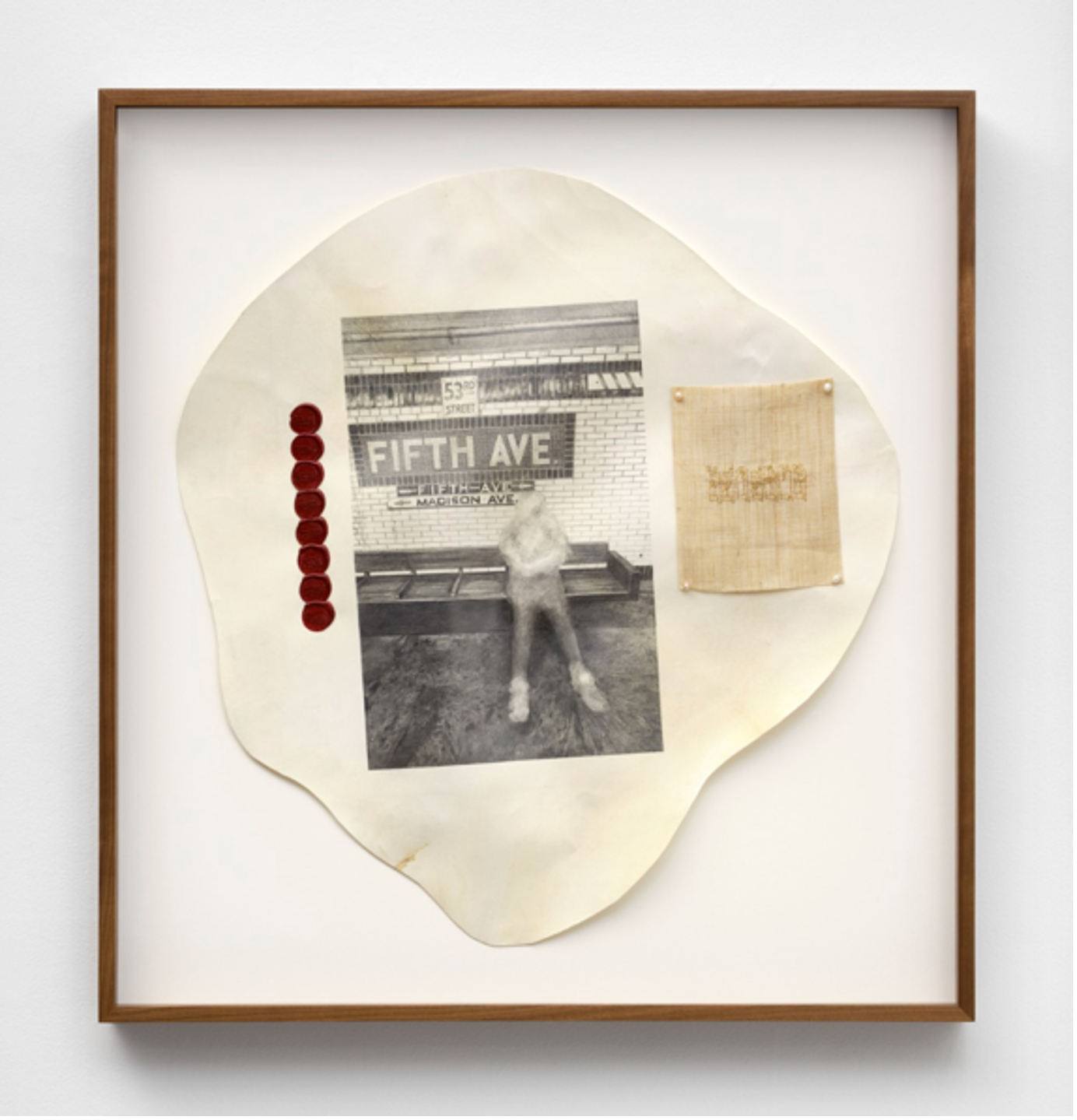

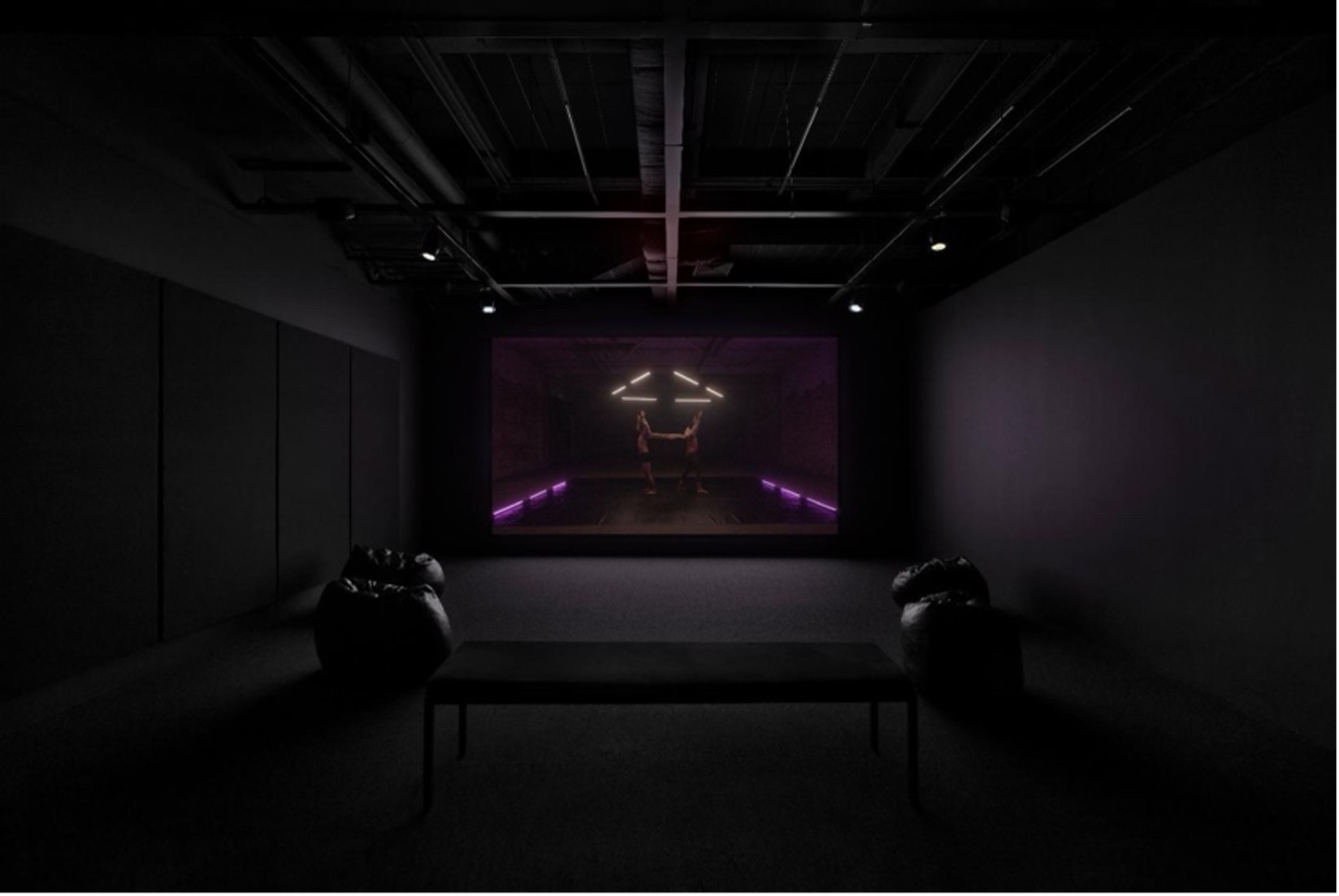

In Kang Seung Lee’s

project, we don’t see an attempt to create a unique, holistic, or coherent

narrative with the hundreds of pieces of paper flying in the air. It is not an

attempt to create a History (with a capital H) of the L.A. Uprising with the

tattered flying pages because that would be a betrayal. The many flying shreds

of paper in his piece, when they come together to compose a whole, appear first

as kites and then as a commemoration of a place, person, or event. The

kites—the Chinese invention that came to the West during the 12th

century and that is known in the Spanish-speaking world as “papalote,” a word

with Nahuatl origin, papalotl, which means butterfly—allows the viewer, in

dialogue with the wind, to trace an itinerary; to invent a choreography for its

movement. That is the type of “stories,” in plural and with small letters, that

we can tell with revolts.

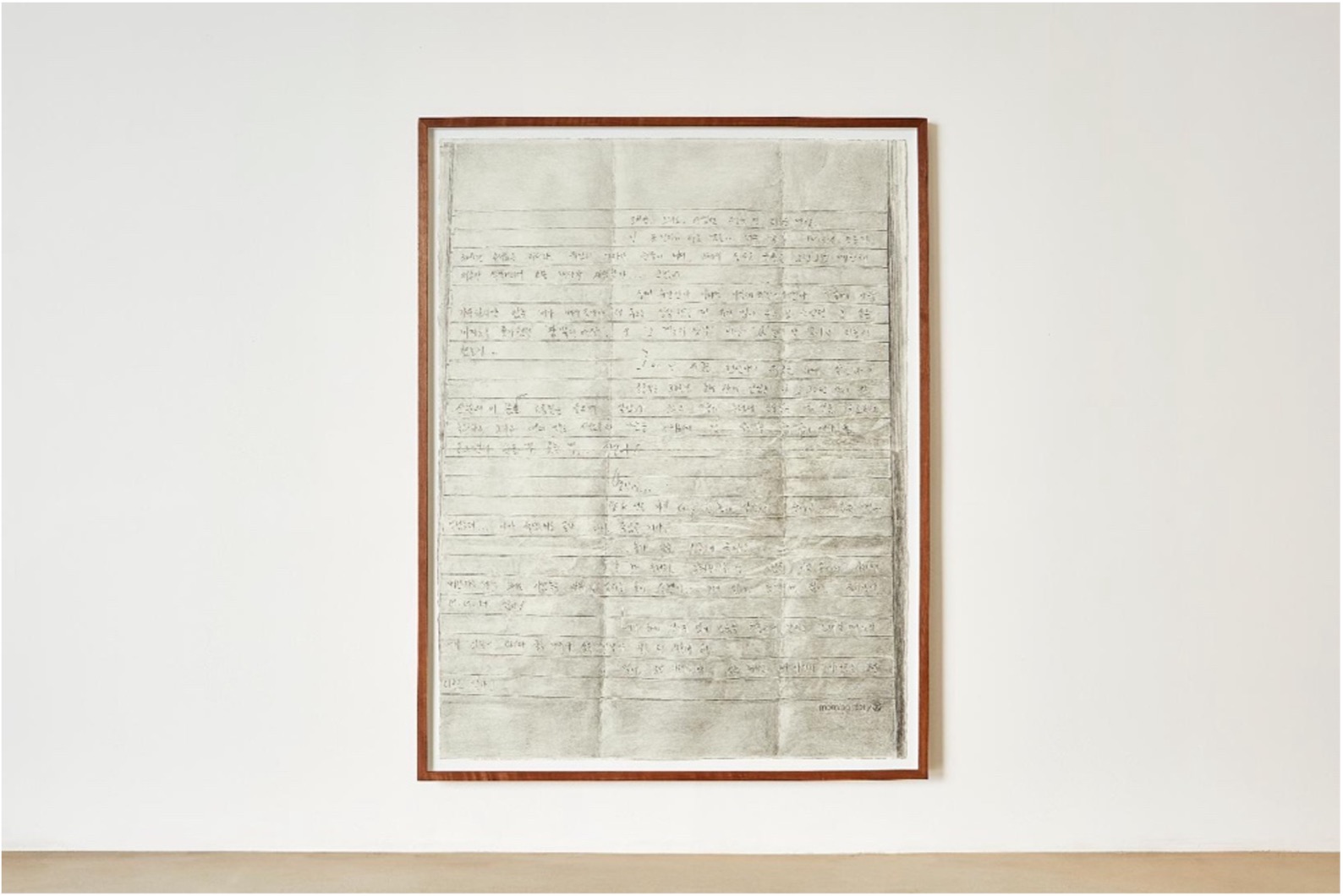

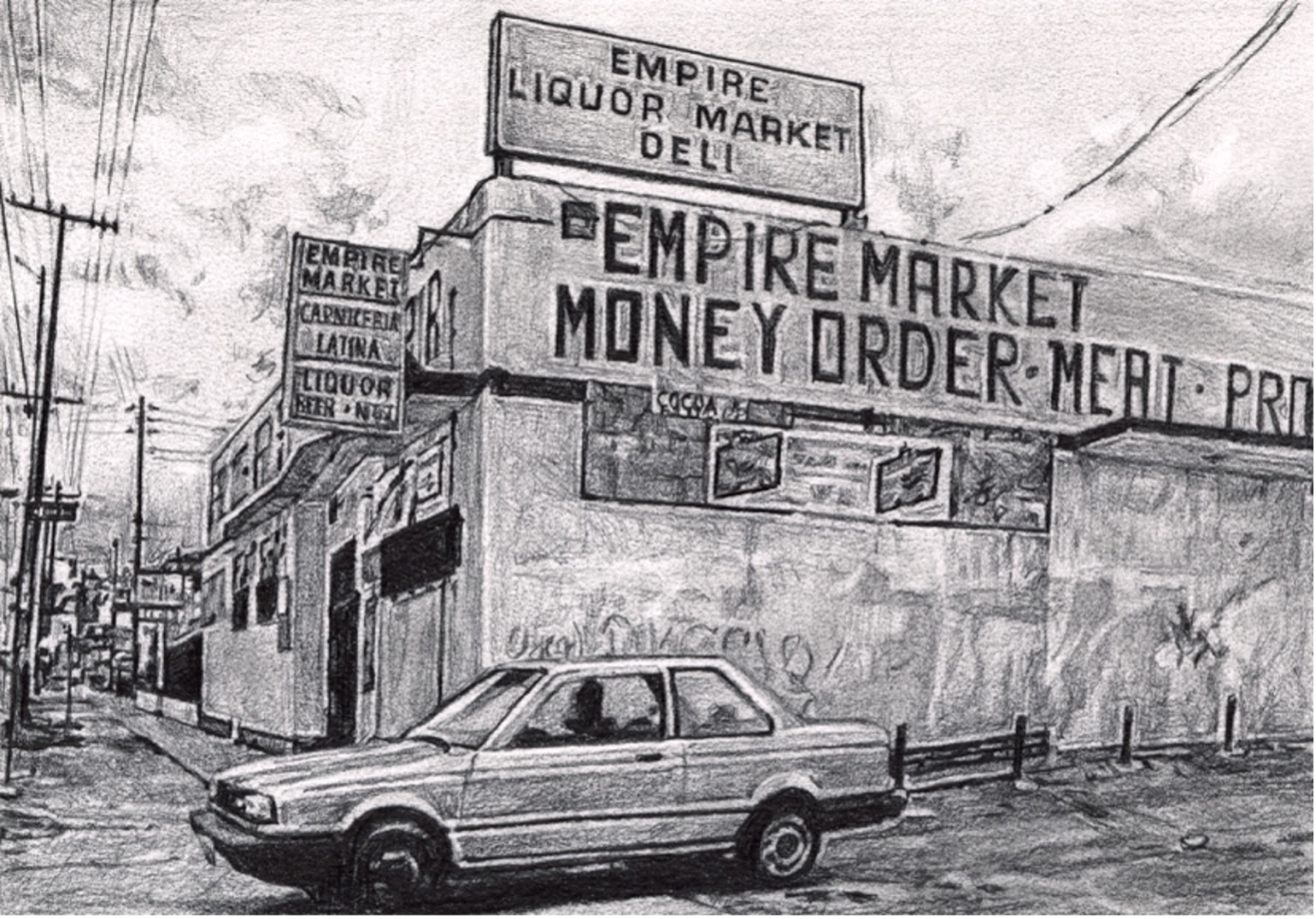

One of Lee’s kites

recreates a packet of information and sworn statements found in the Special

Collection files at the University of Southern California. It was compiled and

prepared by the Central American Refugee Center in 1992 and presented in the

investigation of the joint LAPD/INS activities in the aftermath of the Los

Angeles upheaval of that year. This dossier contains a list of names, a small

sample of the more than 700 people of Central American origin who were detained

and deported during the period of the uprising, and of the more than 100 who

were still being detained at that moment and requested a hearing before a

judge. What we have left of these people are their first names and the first

initial of their last names, and the illegal circumstances under which they

were detained. The other side of history that emerges in these declarations can

be summarized with the following passage from Remnants of

Auschwitz by Giorgio Agamben:

What momentarily shines

through these laconic statements are not the biographical events of personal

histories, as suggested by the pathos-laden emphasis of a certain oral history,

but rather the luminous trail of a different history. What suddenly comes to

light is not the memory of an oppressed existence, but the silent flame of an

immemorial ethos- not the subject's face, but rather the disjunction between

the living being and the speaking being that marks its empty place. Here life

subsists only in the infamy in which it existed; here a name lives solely in

the disgrace that covered it. And something in this disgrace bears witness to

life beyond all biography. (143)*

The layers of experience

that live behind the monuments and the documents, the way in which biographical

commemoration collides with historical commemoration, and the story of a

tragedy that transcends and is more expressive than any biography, are the three

principal traits that configure the concept of material history that I believe

must be used to write the history of an event such as the Los Angeles Uprising

of 1992. Just like the kite that recreates the dossier, each one of Lee’s kites

recreates an image of one of the sites of memory, to use Pierre Nora’s

terminology, that constitute the imaginary of the revolt that occurred in Los

Angeles in 1992. As part of the project Monumental Perspectives, through the

use of Augmented Reality (AR), we see a creation of potential monuments and

commemorations related to the history of L.A. that has been silenced. Real

monuments are an essential part of the pedagogy of a nation and the patriotism

that all countries construct in order to create a monolithic past usually told

by the victors of history. In Lee’s project, the kites create a virtual and

contingent monument through which the power that lies in the past finds a voice

and a face in the present. The kites permit the past to move, dance, and draw

new paths in the sky of L.A. It is a past that does not allow itself to get

trapped in the monolithic fiction of real monuments as it is indomitable and

keeps the spirit of insurgency alive.